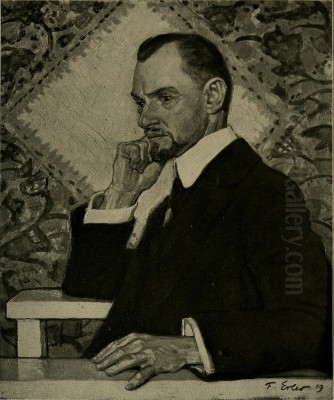

Erich Erler, often known by the appended name Erich Erler-Samedan, stands as a fascinating figure in German art history at the turn of the 20th century. His journey from the graphic arts to becoming a celebrated painter of Alpine landscapes is a testament to personal resilience and the profound influence of environment on artistic vision. Born in a period of significant cultural and artistic change, Erler carved a unique niche for himself, capturing the majestic beauty and specific atmosphere of the Swiss Alps, particularly the Engadine region, which became inextricably linked with his name and artistic identity.

From Silesia to the Graphic Arts

Erich Erler was born on December 16, 1870, in Frankenstein, Silesia, which was then part of Prussia (now Ząbkowice Śląskie, Poland). His early professional life was not initially directed towards painting. Instead, he trained and worked as a printer and bookbinder. These formative years immersed him in the world of design, typography, and the meticulous craft of book production. This background likely instilled in him a strong sense of composition and attention to detail that would later inform his pictorial work.

His involvement in the graphic arts extended beyond mere craft. Erler also took on the role of an editor, demonstrating a broader engagement with visual culture and narrative. During this period, he was involved in the publication of notable works, including series titled Totentanz (Dance of Death) and Die Nibelungen. These projects suggest an early interest in themes of myth, mortality, and dramatic storytelling, elements that, while perhaps less overt in his later landscapes, hint at a deeper romantic sensibility. His brother, Fritz Erler (1868-1940), also became a prominent artist, known for painting, graphic design, and stage design, and the two brothers would later collaborate.

A Life Altered: The Move to Samedan

The trajectory of Erich Erler's life and career took a dramatic turn in the late 1890s due to health concerns. Diagnosed with tuberculosis, a widespread and often debilitating illness at the time, he sought the clear mountain air and therapeutic environment of the Swiss Alps. He moved to the village of Samedan in the high Engadine valley, a location renowned for its sanatoriums and stunning natural beauty. This move, initially driven by necessity, proved to be the catalyst for his transformation into a painter.

Samedan, nestled amidst towering peaks and bathed in unique alpine light, offered not just physical recuperation but immense artistic inspiration. Away from his established profession, Erler began to explore the visual arts, teaching himself to paint. He started with watercolors, a medium well-suited to capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere, before progressing to oil painting. The landscape that surrounded him became his primary subject matter – the imposing mountains, the changing seasons, the vast skies, and the hardy local inhabitants who lived and worked in this dramatic setting.

The Influence of the Engadine and Giovanni Segantini

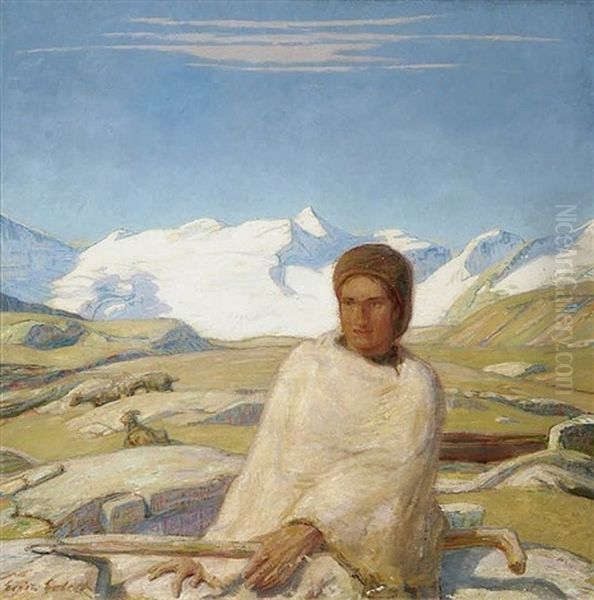

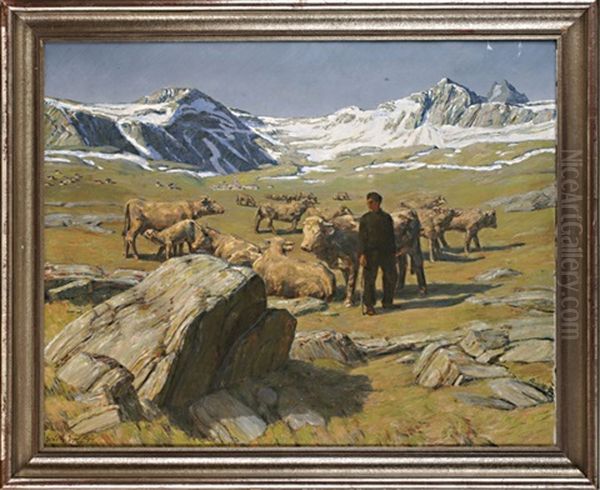

The Engadine valley was not just a picturesque backdrop for Erler; it became the heart of his artistic output. He travelled extensively through the region, sketching and painting en plein air, developing a deep connection with the landscape. His works from this period often depict panoramic mountain vistas, sunlit valleys, and scenes of rural life, such as shepherds tending their flocks against the backdrop of snow-capped peaks.

Crucially, his time in the Engadine brought him into contact with the legacy and circle of the renowned Italian painter Giovanni Segantini (1858-1899). Segantini, famous for his monumental depictions of Alpine life and his unique Divisionist technique, had spent his final years working in the Engadine and died tragically on the Schafberg mountain above Pontresina, near Samedan. Erler did not study directly under Segantini, but he became closely acquainted with Dr. Oskar Bernhard, the physician who had treated Segantini and who also treated Erler for his tuberculosis.

Through Dr. Bernhard and the lingering artistic presence of Segantini, Erler absorbed the influence of the master's approach. While Erler did not fully adopt Segantini's pointillist technique, the older artist's emphasis on light, monumental compositions, and the symbolic weight of the Alpine landscape resonated deeply with him. Erler developed his own style, characterized by strong compositions, a sensitivity to atmospheric conditions, and often a bright, luminous palette suited to the high-altitude light. His friendship with Dr. Bernhard remained strong, and both were involved in the efforts to establish the Segantini Museum in nearby St. Moritz, which opened in 1908, cementing Erler's connection to the artistic heritage of his adopted home.

Munich Connections and Artistic Circles

By 1905, Erich Erler had established himself sufficiently as an artist to maintain residences in both Samedan and Munich. Munich, at this time, was a major centre of artistic innovation in Germany, home to the Munich Secession and the burgeoning Jugendstil movement. While perhaps less radical than some of his contemporaries, Erler engaged with this vibrant scene. His brother, Fritz Erler, was a founding member of the artists' group "Die Scholle," known for its decorative style and association with the magazine Jugend. Erich exhibited alongside such groups and became associated with the broader circle of Munich artists seeking new forms of expression beyond academic constraints.

His growing reputation attracted patrons. Among his notable collectors were members of the Neisser family in Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). Albert and Toni Neisser were significant figures in medicine and culture, known for their extensive art collection and their villa, which served as a meeting place for intellectuals and artists. Their circle included prominent figures like the composer Gustav Mahler and the writer Gerhart Hauptmann. Erler's connection to such patrons underscores his acceptance within sophisticated cultural spheres and provided crucial support for his artistic career. Other artists active in the Munich scene during this era included figures like Franz von Stuck, Lovis Corinth, Max Slevogt, and Wilhelm Trübner, representing various facets of Secessionism, Impressionism, and Symbolism.

The Holzhausen Studio and Mature Work

A significant step in consolidating his career occurred in 1905 when Erich Erler, together with his brother Fritz, established a studio in Holzhausen am Ammersee, a village near Munich popular with artists. This move signified a full commitment to painting, leaving behind his earlier professions entirely. The studio provided a dedicated space for creating larger works and further developing his artistic practice, balancing his time between the stimulating environment of Munich and the inspirational landscapes of the Engadine.

His mature style solidified during this period. He continued to focus on Alpine themes, but also painted landscapes from the Bavarian countryside around Holzhausen, such as his work Icking bei München. His technique often involved applying paint in a way that conveyed both texture and light, sometimes using broad strokes for landscapes and skies, other times employing finer detail for figures or foreground elements. He excelled at capturing the specific moods of the mountains – the crisp clarity of a spring morning, the golden light of late afternoon, or the stark beauty of a winter scene.

Representative Works and Style

Several works exemplify Erich Erler-Samedan's artistic focus and style. Hirtin vor Engadiner Berglandschaft (Shepherdess before Engadine Mountain Landscape) is a characteristic example, placing a figure integral to Alpine life within a grand, luminous mountain setting. The composition likely emphasizes the harmony, or perhaps the contrast, between humanity and the overwhelming scale of nature, a common theme in Alpine painting.

Frühling in den Alpen (Spring in the Alps) would capture the seasonal renewal in the mountains, likely featuring melting snow, emerging greenery, and the particularly intense light of spring at high altitudes. Such works allowed Erler to explore a brighter colour palette and convey a sense of optimism and natural vitality.

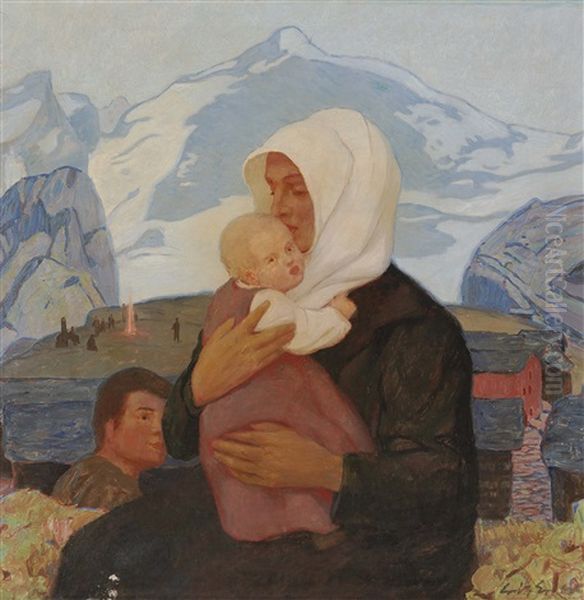

Mutter mit Kind (Mother with Child), while potentially set in an Alpine context, highlights his interest in human subjects as well. This theme, universal yet potentially grounded in the specific environment he knew, allowed for an exploration of tenderness and familial bonds, perhaps imbued with the same sense of quiet dignity he often gave his depictions of local figures.

Icking bei München shows his engagement with the landscape closer to his German base. While different from the high Alps, the Bavarian pre-alpine scenery offered its own charms, which Erler captured with his characteristic sensitivity to light and atmosphere. These works demonstrate his versatility as a landscape painter, not solely confined to the Engadine. His style generally remained representational, focused on capturing the visual truth of the scene, but elevated by a strong sense of design, likely influenced by his graphic arts background and Jugendstil currents, and a profound feeling for the spirit of place.

Context within Art History

Erich Erler-Samedan's work occupies a specific place within the broader context of European art at the turn of the century. He was working during a period of immense artistic ferment, bridging late Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and the rise of Jugendstil (Art Nouveau). While based in Munich, a hub for these developments, his primary focus on Alpine landscapes sets him somewhat apart from the urban subjects or mythological fantasies favoured by some contemporaries like Franz von Stuck or the burgeoning expressionism seen elsewhere in Germany.

His dedication to the Alps aligns him with a tradition of mountain painting, which saw renewed vigour in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work can be considered alongside that of Giovanni Segantini, whose influence was direct, and the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler (1853-1918), known for his powerful, rhythmic, and often symbolic depictions of the Swiss Alps. While Hodler's style was perhaps more stylized and symbolic, both artists shared an interest in conveying the monumental power and spiritual dimension of the mountain world. Erler's work offers a perhaps more naturalistic, yet deeply felt, interpretation compared to Hodler's parallelism.

Compared to German Impressionists like Max Liebermann (1847-1935) or Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), who often focused on modern life, portraiture, or different types of landscapes, Erler remained committed to his chosen Alpine niche. His contemporaries in the Munich scene, such as Leo Putz (1869-1940) or Hans Thoma (1839-1924), explored landscape and figure painting with varying stylistic approaches, from decorative Jugendstil to a more traditional realism. Erler's specific focus and his connection to Samedan gave his work a distinct identity within this diverse landscape. He can also be seen in relation to Austrian Alpine painters like Alfons Walde (1891-1958), though Walde's work often has a bolder, more poster-like quality. Erler's art retains a connection to 19th-century realism while embracing the heightened sense of light and colour characteristic of early 20th-century painting. Artists like Lesser Ury (1861-1931) explored light in urban settings, while Erler explored it in the unique conditions of the high Alps. Ludwig von Hofmann (1861-1945) explored idyllic, arcadian scenes often with a strong Jugendstil linearity, offering a different kind of engagement with nature compared to Erler's more direct landscape focus.

Later Life and Legacy

Erich Erler continued to paint throughout his life, dividing his time between Germany and Switzerland. He remained captivated by the Alpine landscapes that had so profoundly shaped his artistic path. He passed away in 1946. While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his more avant-garde contemporaries or his brother Fritz, Erich Erler-Samedan holds a significant place as a dedicated and skilled interpreter of the Alpine world.

His works continue to appear at auction, particularly in Germany and Switzerland, indicating sustained interest among collectors. Paintings like Hirtin vor Engadiner Berglandschaft and Icking bei München have fetched respectable prices in recent years, confirming their enduring appeal. While specific information about his works in major public museum collections is not readily available in all sources, his connection to important patrons like the Neisser family suggests his work entered significant private collections early on. The mention of institutions like the Alfred Hering Kunsthaus Stuttgart in provenance records points to the circulation of his work through the art trade over the decades.

Erich Erler-Samedan's legacy lies in his authentic and atmospheric depictions of a specific, powerful landscape. His life story – the dramatic shift from graphic artist to painter spurred by illness and a change of environment – is compelling. He successfully translated his deep personal connection to the Engadine into a body of work that celebrates the beauty, light, and enduring majesty of the Alps, securing his position as a noteworthy artist within the German and Swiss art traditions of his time. His paintings serve as a visual testament to the transformative power of nature and the unique artistic vision it inspired in him.