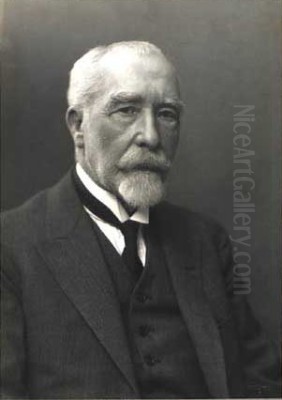

Erik Ludwig Henningsen stands as a significant figure in Danish art history, particularly noted for his contributions to the Social Realism movement during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in Copenhagen on August 29, 1855, into a Denmark undergoing significant social and industrial transformation, Henningsen dedicated much of his artistic career to depicting the lives, struggles, and occasional joys of the common people, especially the urban poor and marginalized groups. His work provides an invaluable visual record of his time, marked by a keen eye for detail, a compassionate perspective, and a commitment to portraying reality, however harsh. He passed away on November 28, 1930, leaving behind a legacy of powerful images that continue to resonate with viewers today.

Henningsen's paintings often explored themes of poverty, social injustice, unemployment, and the stark contrasts between different social classes in rapidly modernizing Copenhagen. Unlike some of his contemporaries who focused on idyllic rural scenes or the lives of the bourgeoisie, Henningsen frequently turned his gaze towards the less comfortable aspects of society. His commitment to realism, combined with a narrative sensibility, allowed him to create works that were not just observations but also subtle commentaries on the human condition within a specific social context. His name is often mentioned alongside his brother, Frants Henningsen, who also pursued similar artistic themes, making the Henningsen brothers key proponents of Danish Realism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Erik Henningsen's journey into the world of art began in Copenhagen. His father worked as a grocer (though some sources mention confectioner), providing a modest middle-class background. Showing artistic inclination early on, he initially trained under the decorative painter A. Hellesen. This foundational experience likely honed his technical skills and attention to detail. He furthered his formal education by attending C.V. Nielsen's drawing school before gaining admission to the prestigious Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi) in 1873.

The Academy provided Henningsen with rigorous training in the academic tradition. During his time there, figures like the historical painter Carl Bloch were influential, representing the established artistic standards. Henningsen, however, would soon gravitate towards the newer currents of Realism and Naturalism that were challenging academic conventions across Europe. He proved to be a talented student, graduating in 1877 and receiving the Academy's small silver medal that same year. This early recognition hinted at the promising career that lay ahead. His education provided him with the technical mastery necessary to tackle the complex figurative compositions that would characterize his later work.

His family environment also played a role, particularly his relationship with his elder brother, Frants Henningsen (1850-1908). Frants also attended the Royal Danish Academy and became a notable painter and illustrator, often exploring similar social themes and genre scenes. While each developed his own distinct style, their shared interest in depicting contemporary Danish life created a parallel artistic path, and their works are often discussed in relation to each other within the context of Danish Realism.

The Rise of Social Realism in Denmark

The latter half of the 19th century in Denmark was a period of profound change, often referred to as the "Modern Breakthrough" (Det Moderne Gennembrud). Championed by the influential literary critic Georg Brandes, this movement called for art and literature to engage with contemporary social issues and abandon the idealized romanticism of the past. Industrialization was transforming Copenhagen, leading to urban growth, new social classes, and increased awareness of poverty, labor conditions, and social inequality.

This cultural climate provided fertile ground for Realism and Naturalism. Artists across Europe, inspired by pioneers like Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet in France, began to depict everyday life with unflinching honesty. In Denmark, painters started turning away from mythological or historical subjects and towards the realities of their own time. While the Skagen Painters, such as P.S. Krøyer, Michael Ancher, and Anna Ancher, famously captured the light and life of the fishing communities in northern Jutland, other artists focused on the social fabric of the cities and the changing countryside.

Erik Henningsen emerged as a leading voice within this urban-focused Social Realism. He embraced the call to depict contemporary life and its problems. His work aligned with the spirit of the Modern Breakthrough, using art as a means of observation and, implicitly, social commentary. He became associated with groups like "Bogstavelighed" (Literalness or Realism League), an association of artists and writers who aimed to promote realism and use their work to foster debate and inspire social improvement. This commitment set him apart from artists pursuing purely aesthetic goals or more traditional subjects.

A Commitment to Social Commentary

Henningsen's dedication to portraying the plight of the less fortunate became a defining characteristic of his oeuvre, particularly during the 1880s and 1890s. He did not shy away from depicting difficult subjects, bringing attention to the harsh realities faced by many in Copenhagen and beyond. His paintings often served as visual narratives, telling stories of hardship, resilience, or systemic injustice, inviting empathy and reflection from the viewer.

One of his most powerful works from this period is Sat ud (Evicted), painted in 1892. This poignant scene depicts a family and their meager belongings cast out onto the cold street, presumably unable to pay rent. The bleakness of their situation, the despair on their faces, and the indifference of the urban environment create a powerful indictment of social vulnerability. The painting exemplifies Henningsen's ability to capture emotional weight through realistic detail and carefully constructed composition, forcing viewers to confront the human cost of poverty.

Another significant and challenging work is Summum jus, summa injuria. Barnemordet (The Highest Justice is the Greatest Injustice. The Infanticide), completed in 1886 and now housed in The Hirschsprung Collection. This painting tackles the desperate act of infanticide, often linked to the extreme poverty and social stigma faced by unmarried mothers. By choosing such a harrowing subject, Henningsen pushed the boundaries of acceptable themes in art, highlighting the tragic consequences of societal pressures and lack of support for vulnerable women. His approach was observational rather than sensational, focusing on the grim reality and the legal or social aftermath, prompting contemplation on justice and mercy.

Through works like these, Henningsen established himself as an artist deeply engaged with the social issues of his day. He gave visibility to those often overlooked – the unemployed, the evicted, struggling workers, vulnerable women, and children facing hardship. His paintings functioned as social documents, capturing aspects of Danish society that more idealized art forms ignored. He shared this focus on social conditions with contemporaries like L.A. Ring, although Ring often explored these themes through the lens of rural life and symbolism, while Henningsen's focus remained more directly observational and often urban.

Masterpieces of Observation and Narrative

Beyond his most overtly critical works, Henningsen created numerous paintings that captured various facets of Danish life with remarkable skill and insight. His ability to observe and render human interaction, social settings, and atmospheric detail made his genre scenes particularly compelling.

En bonde i hovedstaden (A Peasant at the Capital, 1887) depicts a rural family, perhaps visiting Copenhagen for the first time, looking somewhat lost and out of place amidst the city environment. This work subtly explores the cultural and social gap between the countryside and the rapidly growing capital, a common theme during Denmark's modernization. It highlights the contrasts in dress, demeanor, and experience, capturing a moment of transition and perhaps alienation.

Perhaps Henningsen's most widely recognized image today is Den tørstige mand (The Thirsty Man), created in 1900. Commissioned as an advertising poster for Tuborg Breweries, the painting depicts a stout, sweating man pausing on a hot country road, clearly in need of refreshment. While intended for commercial use, the image became incredibly popular and has achieved iconic status in Danish culture. It showcases Henningsen's skill in creating relatable, characterful figures and capturing a simple, universal moment, even within a commercial context. Its enduring appeal speaks to its successful blend of realism and accessible narrative.

Henningsen also depicted scenes of leisure and social gathering, though often with an underlying awareness of social context. Ballet (The Ball, 1889/1890) portrays a lively dance hall scene, capturing the movement, fashion, and social dynamics of a Copenhagen gathering. Similarly, Kunstkritikere (The Art Critics, 1915), now in the Hope Gallery in Salt Lake City, shows two men – perhaps a bartender and a patron – examining an unframed painting in a bar setting. This work offers a glimpse into everyday life where art appreciation occurs outside formal galleries, reflecting on the accessibility and discussion of art within different social spheres.

Technique and Artistic Style

Erik Henningsen's style is firmly rooted in Realism and Naturalism. He possessed a strong command of academic technique, evident in his accurate drawing, convincing portrayal of human anatomy and expression, and well-structured compositions. He typically employed a relatively detailed finish, ensuring that the social environments and the figures inhabiting them were rendered with clarity and believability.

His use of color was often keyed to the mood and subject matter. For his more somber social realist themes like Evicted or Infanticide, he tended towards a darker, more muted palette, emphasizing the bleakness and hardship of the scenes. Grays, browns, and subdued earth tones dominate, contributing to the overall emotional weight. However, he was also capable of using brighter colors and capturing the effects of light effectively, as seen in outdoor scenes or works like The Thirsty Man. His handling of light and shadow was crucial in creating atmosphere and focusing attention on key narrative elements within the composition.

Compared to the Skagen Painters like P.S. Krøyer or Michael Ancher, known for their vibrant depictions of coastal light, Henningsen's work often feels more grounded, perhaps more 'photographic' in its commitment to representing the unvarnished reality of urban and working-class life. His approach shows affinities with French Naturalists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, who influenced many Scandinavian artists with his detailed rendering of rural figures and landscapes, although Henningsen adapted this detailed realism primarily to urban and social subjects. He avoided the looser brushwork and brighter palette associated with Impressionism, remaining committed to a more solid, descriptive form of representation throughout his career.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

Like many artists of his generation, Erik Henningsen sought inspiration and exposure beyond Denmark's borders. He undertook several study trips abroad, facilitated in part by awards like the Ancher Prize (1889) and a travel scholarship received in 1892. His travels took him to important European art centers, including Germany, Italy, France, and the Netherlands.

These journeys would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic movements and contemporary artists. In Germany, he might have encountered the works of Realists like Wilhelm Leibl or the historical and genre scenes of Adolph Menzel. France, particularly Paris, was the undisputed center of the art world, offering exposure to ongoing debates between academic art, Realism, Naturalism, and the emerging Impressionist and Post-Impressionist styles. Italy offered the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Baroque, reinforcing classical principles of composition and figure drawing.

While Henningsen's core style remained consistent with Danish Realism, these travels likely broadened his perspectives and reinforced his commitment to figurative art grounded in observation. Exposure to international art may have confirmed his chosen path rather than drastically altering it, perhaps strengthening his resolve to depict Danish reality with the technical skill and narrative depth he admired in both historical and contemporary European art. The specific impact of these travels on individual works is difficult to trace precisely, but they undoubtedly contributed to his development as an artist operating within a broader European context.

Later Career and Genre Scenes

While Henningsen remained active as an artist well into the 20th century, the intense focus on overtly critical social realism that characterized his work in the 1880s and 1890s seemed to lessen somewhat in his later years. He continued to paint scenes of Danish life, but his focus often shifted towards more general genre subjects, depicting everyday interactions, family moments, and street scenes without the same sharp edge of social critique found in works like Evicted.

During this period, he also undertook significant public commissions. Notably, he painted murals for the banquet hall (Festsal) in the University of Copenhagen's main building. These large-scale works required a different approach than his easel paintings, demanding skills in historical or allegorical representation suitable for a prestigious institutional setting. This commission demonstrated his established reputation and versatility as an artist.

Paintings like Bedstefar og den uartige dreng (Grandpa and the Naughty Boy, also known as Testing Grandfather's Pipe, 1881, though possibly revisited or similar themes painted later) exemplify his interest in charming, anecdotal genre scenes. These works often depicted intergenerational relationships or humorous moments from everyday life, rendered with his characteristic realism and attention to detail. While less politically charged than his earlier work, these paintings still offer valuable insights into the customs and social life of the period. His later street scenes, like Legen. Københavnshavets Gadebillede (1919), continued to capture the energy and atmosphere of Copenhagen.

Recognition and Exhibitions

Erik Henningsen achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, both within Denmark and internationally. He was a regular exhibitor at the prestigious Charlottenborg Spring Exhibition in Copenhagen, the main venue for contemporary Danish art, showcasing his works there frequently from the late 1870s onwards. His paintings were often noted for their technical skill and topical subject matter.

His talent was acknowledged through several awards, including the Royal Danish Academy's annual medal (Neuhausens Præmie) in 1887 and the coveted Ancher Prize in 1889, which supported his travels. He also received the Academy's highest honor, the Thorvaldsen Medal, in 1890, cementing his status within the Danish art establishment despite the sometimes challenging nature of his subjects.

Henningsen's work was also shown internationally. He participated in major exhibitions such as the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1889, where he received recognition, as well as exhibitions in Munich and Berlin. This international exposure helped to place Danish Realism, and Henningsen's contributions to it, within a broader European context. Today, his works are held in major Danish museum collections, including the National Gallery of Denmark (Statens Museum for Kunst), The Hirschsprung Collection, and ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, as well as finding places in international collections like the Hope Gallery in the United States.

Legacy and Influence

Erik Ludwig Henningsen's legacy lies primarily in his role as one of Denmark's foremost Social Realist painters. Alongside his brother Frants, he brought a new level of attention to the lives of the urban working class and the social problems accompanying Denmark's industrialization. His paintings serve as powerful historical documents, offering insights into the social conditions, class structures, and everyday realities of late 19th and early 20th century Denmark.

His commitment to realism and social commentary placed him firmly within the Modern Breakthrough movement, aligning his artistic goals with the broader cultural push towards addressing contemporary issues. While perhaps less formally innovative than some contemporaries like Vilhelm Hammershøi, whose introspective interiors explored different aesthetic territory, or Kristian Zahrtmann, known for his bold use of color and historical subjects, Henningsen's strength lay in his narrative clarity and empathetic portrayal of the human condition.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of realist traditions in Danish art and in the ongoing appreciation for art that engages with social themes. His works remain relevant for their historical insights and their artistic quality. The enduring popularity of images like The Thirsty Man also speaks to his ability to connect with a broad audience through relatable human moments. He remains a key figure for understanding the development of Danish art during a pivotal period of national transformation, valued for his technical skill, his observant eye, and his compassionate focus on the lives of ordinary Danes.

Conclusion

Erik Ludwig Henningsen carved a distinct and important niche for himself within Danish art history. As a prominent exponent of Social Realism, he used his considerable technical skills to document and comment upon the profound social changes sweeping through Denmark during his lifetime. From the harsh realities of poverty and eviction depicted in his earlier works to the lively genre scenes and iconic advertising images of his later career, Henningsen consistently demonstrated a keen eye for human detail and a deep engagement with the world around him. His paintings offer more than just aesthetic pleasure; they provide a window into the past, capturing the struggles, complexities, and everyday moments of Danish society with honesty and empathy. His legacy endures in the powerful images he created, securing his place as a significant chronicler of his time and a master of Danish Realism.