Eugène Jules Joseph Laermans stands as a pivotal figure in Belgian art, a painter and printmaker whose poignant depictions of the working class and rural poor carved a unique niche in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work, deeply imbued with a sense of social consciousness and a somber, often tragic, worldview, not only captured the zeitgeist of an industrializing nation grappling with profound social change but also prefigured the emotional intensity of Belgian Expressionism. Born into a world he would soon experience primarily through sight, Laermans translated his observations into powerful visual statements that continue to resonate with their raw honesty and profound empathy.

Early Life and Formative Challenges

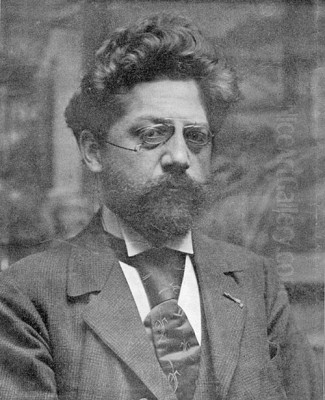

Eugène Laermans was born on October 21, 1864, in Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, a then-burgeoning, now integral, part of Brussels. His early life was marked by a profound personal tragedy that would irrevocably shape his artistic path. At the tender age of eleven, a severe bout of meningitis left him deaf and nearly mute. This sudden and isolating sensory deprivation channeled his focus intensely towards the visual world. Art became not just a passion but his primary means of communication and engagement with his surroundings.

This early adversity seems to have heightened his visual acuity and fostered a deep empathy for those on the margins of society. Unable to fully participate in the auditory world, Laermans became an acute observer of human gesture, expression, and the silent narratives embedded in the lives of ordinary people. His physical limitations, rather than hindering his artistic development, arguably fueled his unique perspective, allowing him to perceive and convey a depth of human experience often overlooked by his contemporaries.

Artistic Education and Influences

Laermans' formal artistic training began at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, which he attended from 1887 to 1889. Here, he studied under Jean-François Portaels, a respected academic painter known for his Orientalist scenes and portraits. While Portaels provided a solid foundation in traditional techniques, Laermans' artistic spirit was soon drawn to more contemporary and radical influences.

A significant early impact came from the work of Félicien Rops, a fellow Belgian artist whose provocative and often macabre Symbolist etchings explored themes of eroticism, death, and social satire. Rops's unflinching gaze and his willingness to tackle controversial subjects likely resonated with Laermans' own developing critical perspective. The dark, often unsettling, undertones in Rops's art found an echo in Laermans' later depictions of societal struggles.

The literary world, particularly the poetry of Charles Baudelaire, also profoundly shaped Laermans' artistic vision. Baudelaire's Les Fleurs du Mal (The Flowers of Evil), with its exploration of urban alienation, spleen, and the beauty found in decay, became a touchstone for the Decadent movement, which Laermans joined around 1890. He even created illustrations for Baudelaire's work, demonstrating a deep affinity with the poet's themes of modern suffering and the plight of the individual in an indifferent world. The influence of writers like Émile Zola, with his naturalistic portrayals of the working class, can also be discerned in Laermans' thematic concerns.

The Social Conscience of a Painter

At the heart of Laermans' oeuvre lies a profound social conscience. He turned his gaze away from the idealized subjects favored by academic art and instead focused on the harsh realities faced by peasants, factory workers, and the urban poor. His canvases are populated by figures burdened by labor, poverty, and a sense of hopelessness, reflecting the social dislocations wrought by industrialization in Belgium.

His depictions of rural life were far removed from the pastoral idylls painted by some of his predecessors. Instead, Laermans, much like the French Realist Jean-François Millet, portrayed peasants with a stark honesty, emphasizing the toil and hardship of their existence. However, Laermans' vision was often bleaker, less romanticized than Millet's, imbued with a pervasive sense of struggle against an unforgiving environment and an unjust social order. He captured the stoicism, but also the deep weariness, of those tied to the land.

Similarly, his portrayals of urban workers and the dispossessed highlighted the grim conditions of industrial life. He depicted crowded, impoverished streets and the anonymous, often dehumanized, figures of the laboring masses. These works serve as powerful social documents, offering a critical perspective on the underside of progress and prosperity. His approach can be compared to that of Honoré Daumier, whose caricatures and paintings also critiqued social and political injustices, though Laermans' style was generally less satirical and more overtly tragic.

Key Artistic Movements and Affiliations

Laermans' artistic journey saw him engage with several key artistic currents of his time, though he always maintained a distinct personal style. His early alignment with the Decadent movement reflected his interest in Baudelairean themes and a rejection of bourgeois conventions. This movement, characterized by its fascination with the morbid, the artificial, and the psychologically complex, provided an initial framework for his exploration of darker human experiences.

His work is also strongly associated with Social Realism. This broad movement, which gained prominence in the mid-19th century with artists like Gustave Courbet, aimed to depict ordinary people and everyday situations with truthfulness and objectivity, often highlighting social inequalities. Laermans was a key Belgian proponent of this ethos, using his art to give visibility to the often-invisible struggles of the lower classes.

Symbolism also left an indelible mark on Laermans' art. While not a Symbolist in the esoteric or mystical vein of artists like Fernand Khnopff or Jean Delville, Laermans employed symbolic elements to heighten the emotional and psychological impact of his scenes. His figures often transcend mere representation to become archetypes of suffering, alienation, or endurance. The stark landscapes and expressive figures in his paintings carry a weight of meaning that goes beyond literal depiction. James Ensor, another towering figure in Belgian art, also used Symbolist and proto-Expressionist means to critique society, though Ensor's approach was often more fantastical and grotesque.

Laermans was active in the vibrant Brussels art scene, participating in avant-garde circles. He was involved with artistic groups such as "Voorwaarts" (Forward) from 1891 and "Pour l'Art" (For Art) from 1892. These associations provided platforms for exhibiting his work and engaging with like-minded artists who sought to break from academic constraints. His participation in the exhibitions of La Libre Esthétique, a successor to the influential Les XX group (founded by Octave Maus), further cemented his position within the progressive art movements of Belgium. La Libre Esthétique was known for showcasing a wide range of international avant-garde art, including works by Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, and Art Nouveau artists.

Masterworks of Social Commentary

Several of Laermans' paintings stand out as powerful testaments to his artistic vision and social concerns. These works are characterized by their monumental quality, their somber palettes, and their profound emotional depth.

The Emigrants Triptych (1896) is arguably his most famous work and a cornerstone of Belgian Social Realism. This large-scale triptych depicts the heartbreaking departure of impoverished rural families forced to seek a new life elsewhere. The central panel shows a desolate group trudging along a bleak road, their figures hunched and silhouetted against a vast, indifferent sky. The side panels elaborate on the theme of displacement and loss. The work is a powerful indictment of the economic conditions that drove mass emigration and captures the universal sorrow of leaving one's homeland. The figures are rendered with a stark simplicity that emphasizes their collective plight, reminiscent of the peasant processions in the works of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, albeit infused with a modern sense of despair.

The Blind Man (1898) is another iconic piece, deeply personal yet universally resonant. It portrays a solitary blind man, guided by three figures (often interpreted as his family or perhaps symbolic representations of fate or society), moving through a stark, almost barren landscape. The figures are elongated and somewhat distorted, their movements heavy and labored. The painting evokes a profound sense of vulnerability, isolation, and the human struggle against adversity. Given Laermans' own sensory deprivations, this work carries a particular poignancy, suggesting a deep empathy with those who experience the world differently. The composition and emotional intensity prefigure Expressionist concerns.

A Strike Evening (or Evening of a Strike, 1894) tackles the theme of industrial unrest. It depicts a group of striking workers, their faces grim and determined, gathered in the fading light. The atmosphere is tense and somber, conveying the gravity of their situation and the collective power of their protest. Laermans does not romanticize the scene but presents it with a raw, unvarnished realism that underscores the workers' struggle for dignity and justice. This work aligns with a broader European tradition of depicting labor movements, seen in the works of artists like Käthe Kollwitz in Germany, who also focused on the plight of the working class with profound empathy.

Other notable works include A Moment's Respite, which captures a fleeting moment of rest for a poor family, and his illustrations for Georges Eekhoud's novel La Nouvelle Carthage, which, like Laermans' paintings, explored the harsh realities of urban life in Belgium.

Style and Technique

Laermans developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by its strong linearity, simplified forms, and often somber color palette. He favored broad, flat areas of color, often outlined with dark, decisive contours, which gave his figures a monumental and somewhat sculptural quality. This emphasis on line and silhouette can be seen as a precursor to the graphic power of later Expressionist works.

His compositions are often stark and dramatic, with figures silhouetted against expansive, empty landscapes or oppressive urban settings. He masterfully used light and shadow not just for naturalistic effect but to create mood and emphasize the emotional state of his subjects. A low horizon line frequently accentuates the vastness of the sky, often depicted as heavy and overcast, contributing to the overall sense of melancholy or foreboding.

There is a deliberate avoidance of anecdotal detail in many of his works. Instead, Laermans focused on capturing the essential gesture, the telling posture, the collective mood. His figures, though individualized in their suffering, often take on an archetypal quality, representing broader human conditions. This simplification and emphasis on emotional expression are key elements that link him to the burgeoning Expressionist sensibility.

The influence of Pieter Bruegel the Elder is often cited in discussions of Laermans' style, particularly in his peasant scenes and processional compositions. Like Bruegel, Laermans had an eye for the telling detail of rural life and a capacity to depict large groups of figures with a sense of dynamic movement. However, Laermans' world is generally darker, more overtly tragic, than Bruegel's, reflecting the anxieties and social critiques of his own era. He was sometimes referred to as a "modern Bruegel" or the "Bruegel of the Proletariat."

A Precursor to Belgian Expressionism

While Laermans is firmly rooted in the traditions of Realism and Symbolism, his work is widely recognized as an important precursor to Belgian Expressionism. Several aspects of his art anticipate the core tenets of this later movement:

Firstly, his emphasis on subjective emotion over objective reality. Laermans did not merely record what he saw; he imbued his scenes with his own profound feelings of empathy, sorrow, and sometimes anger. The emotional charge of his paintings is palpable.

Secondly, his use of distortion and simplification for expressive effect. The elongated figures, the stark compositions, and the non-naturalistic use of color and light in some of his works serve to heighten the emotional impact, a technique that would be central to Expressionist artists.

Thirdly, his focus on themes of alienation, suffering, and the struggles of the individual or marginalized groups. These themes became central concerns for Expressionist painters like Constant Permeke, Gustave De Smet, and Frits Van den Berghe, who formed the core of the Latem School of Belgian Expressionism. These artists, working in the early to mid-20th century, built upon the foundations laid by artists like Laermans, pushing further into subjective and emotionally charged depictions of reality.

While Laermans may not have identified as an Expressionist himself, his powerful visual language, his social engagement, and his willingness to explore the darker aspects of human experience paved the way for the generation of artists who would fully embrace the Expressionist ethos in Belgium. His work shares an affinity with other proto-Expressionist figures in Europe, such as Edvard Munch in Norway or even aspects of Vincent van Gogh's later work, particularly in their shared intensity and focus on the human condition.

Later Years and Legacy

Laermans' artistic career was tragically cut short. His eyesight, which had been his primary connection to the world and the wellspring of his art, began to deteriorate. By 1924, he was effectively blind and forced to give up painting. This second profound sensory loss must have been devastating for an artist so reliant on his visual perception. He lived his remaining years in relative obscurity, his most productive period behind him.

Eugène Laermans passed away in Brussels on February 22, 1940, at the age of 75. Despite the premature end to his painting career, he left behind a significant body of work that continues to be celebrated for its artistic power and social relevance.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a Social Realist, he provided an invaluable visual record of the lives and struggles of the Belgian working class and peasantry at a critical juncture in the nation's history. His paintings serve as enduring reminders of the human cost of industrialization and social inequality.

As a Symbolist, he infused his realistic depictions with deeper layers of meaning, transforming ordinary scenes into powerful allegories of the human condition. His figures, burdened yet resilient, speak to universal themes of suffering, endurance, and the search for dignity.

And as a precursor to Expressionism, he helped to shift the focus of art towards subjective experience and emotional intensity, influencing a subsequent generation of Belgian artists. His bold compositions, expressive figures, and somber mood anticipated many of the stylistic and thematic concerns of 20th-century art.

Today, Laermans' works are held in major Belgian museums, including the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp. They stand as a testament to an artist who, despite profound personal challenges, used his immense talent to give voice to the voiceless and to create a body of work that is both historically significant and enduringly moving. He remains a crucial figure for understanding the evolution of modern art in Belgium and the enduring power of art to confront social realities. His contemporaries, such as the sculptor Constantin Meunier, also explored themes of labor, but Laermans brought a unique, painterly melancholy to these subjects.

Conclusion

Eugène Laermans was more than just a painter of his time; he was a visionary who transcended the artistic conventions of his era to create a deeply personal and socially resonant art. His life, marked by the challenge of deafness, became a testament to the power of visual expression. Through his unflinching portrayals of the marginalized, he not only documented the social fabric of late 19th and early 20th century Belgium but also explored universal themes of human suffering, resilience, and the quest for social justice.

His stylistic innovations, bridging Realism, Symbolism, and a nascent Expressionism, mark him as a transitional figure of great importance. By prioritizing emotional truth and subjective experience, Laermans, alongside artists like James Ensor, laid critical groundwork for the development of Belgian Expressionism. His legacy endures in his powerful canvases, which continue to challenge viewers to confront uncomfortable truths and to recognize the profound humanity in those often overlooked by society. Eugène Laermans remains a compelling and vital voice in the grand narrative of European art.