Ernst Kolbe stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in early 20th-century German art. Born in an era of profound artistic transformation, Kolbe navigated the currents of Impressionism, the burgeoning influence of modern sculpture, and the dynamic cultural landscape of Germany. His journey from painter to sculptor, and his unique synthesis of prevailing artistic ideas, mark him as an artist who, while perhaps not achieving the household-name status of some contemporaries, contributed to the rich tapestry of European art at a pivotal time. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, signature style, key works, and his place within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

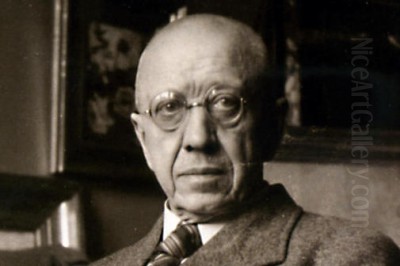

Ernst Kolbe was born in Marienwerder, West Prussia (now Kwidzyn, Poland), on March 9, 1876. His early artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training in painting. He initially enrolled at the prestigious Berlin Art Academy, where he studied painting and drawing under the tutelage of Julius Ehrentraut and Paul Prozess. These instructors would have grounded him in the academic traditions prevalent at the time, emphasizing technical skill, anatomical accuracy, and established compositional principles.

Seeking further refinement and perhaps a different pedagogical approach, Kolbe began private studies with Eugen Bracht in 1899. Bracht was a significant landscape painter, known for his atmospheric and often melancholic depictions of nature, initially influenced by Romanticism but later moving towards Impressionistic tendencies. This mentorship likely exposed Kolbe to newer ways of seeing and representing the world, particularly concerning light and color.

In 1903, Kolbe followed Bracht to Dresden, where Bracht had accepted a professorship. Dresden, at this time, was a vibrant artistic center, home to the Brücke group (founded in 1905) and a burgeoning Expressionist movement. While Kolbe's own style would lean more towards Impressionism and a classical sensibility in sculpture, the energetic atmosphere of Dresden undoubtedly contributed to his artistic environment. He continued as Bracht's student, further honing his skills as a painter.

His connection to the established art world was solidified when he returned to Berlin in 1906. He became a member of the Berlin Artists' Association (Verein Berliner Künstler), an important institution that organized exhibitions and provided a platform for artists. His talent was recognized in 1913 when he received a scholarship from this association, a mark of esteem and support that would have been crucial for a developing artist.

The Pivotal Shift: Rome and the Allure of Sculpture

A significant turning point in Ernst Kolbe's artistic trajectory occurred during his stay in Rome, which lasted from 1898 to 1901. Italy, with its unparalleled wealth of classical and Renaissance art, has long been a pilgrimage site for artists seeking inspiration and a deeper understanding of form and human representation. It was in this historically rich environment that Kolbe's interest in sculpture began to blossom. The tactile nature of sculpture, its three-dimensional presence, and its direct engagement with form and space, must have offered a compelling new avenue for artistic expression beyond the two-dimensional canvas.

Following his transformative years in Rome, Kolbe's path led him to Paris. The French capital was, at the turn of the century, the undisputed epicenter of the avant-garde. It was here that he encountered the revolutionary work of Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Rodin had fundamentally redefined sculpture, moving away from static, idealized forms towards a more dynamic, emotionally charged, and texturally rich representation of the human body. His emphasis on the play of light on surfaces, the fragmentation of form, and the expression of inner turmoil left an indelible mark on modern sculpture.

Kolbe was profoundly influenced by Rodin's approach, particularly the way Rodin's surfaces seemed to capture and reflect light, imbuing the bronze or marble with a sense of life and movement. This "reflective surface" quality became a key element that Kolbe would later integrate into his own sculptural work.

Forging a Unique Sculptural Language: Maillol and Rodin

While Rodin's impact was crucial, Kolbe's mature sculptural style was not a mere imitation. He skillfully synthesized Rodin's expressive surfaces with the formal classicism and serene monumentality of another giant of modern sculpture, Aristide Maillol (1861-1944). Maillol, a French sculptor, offered a counterpoint to Rodin's dramatic intensity. His work emphasized harmonious volumes, simplified forms, and a sense of timeless calm, often drawing inspiration from archaic Greek sculpture. Maillol's figures, predominantly female nudes, possess a weighty, earthy quality and a quiet dignity.

Ernst Kolbe's genius lay in his ability to weave together these seemingly distinct influences. He adopted Maillol's concern for clear, well-defined forms and a certain classical poise, but animated these forms with Rodin's sensitivity to surface texture and the interplay of light and shadow. This fusion resulted in sculptures that were both structurally sound and visually vibrant, formally composed yet imbued with a subtle dynamism.

His thematic concerns often revolved around idealized nudes and youthful figures. These subjects allowed him to explore the beauty of the human form, often imbuing his works with a gentle, elegant, and sometimes lyrical spirit. There was a pursuit of harmony, not just in form, but also in the perceived emotional state of his figures – a sense of quiet contemplation or serene vitality. This contrasted with the more overt psychological drama found in some of Rodin's pieces or the raw emotionality of the German Expressionists.

Impressionistic Roots and Artistic Style

Even as he dedicated himself to sculpture, Ernst Kolbe's background as a painter, particularly one working in an Impressionist style, continued to inform his artistic vision. Impressionism, with its focus on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and atmosphere, and a subjective experience of reality, might seem distant from the solidity of sculpture. However, the Impressionist sensibility for light's behavior on surfaces found a direct translation in Kolbe's sculptural practice.

His attention to the "reflective surfaces" inherited from Rodin can be seen as an extension of Impressionist concerns. Just as painters like Claude Monet (1840-1926) or Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) studied how light fractured and dissolved forms, Kolbe understood that the texture of a bronze surface could be manipulated to catch and scatter light, creating a sense of vibrancy and dematerializing the sheer weight of the medium.

His paintings, though less discussed than his sculptures, would have reflected this Impressionistic approach. Works like "Am Fenster" (At the Window), a known painting by Kolbe, likely showcased his ability to render light, mood, and atmosphere through painterly brushwork and a nuanced color palette. This foundation in observing and translating the visual effects of light provided a unique perspective when he approached the three-dimensional challenges of sculpture. His sculptures, therefore, often possess a painterly quality in their surface treatment, inviting the viewer's eye to travel across the varied textures and subtle shifts in light and shadow.

Representative Works: Embodiments of a Vision

Several works exemplify Ernst Kolbe's artistic style and thematic preoccupations. While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be elusive, certain pieces and series are indicative of his contributions.

"Am Fenster" (Painting): As mentioned, this painting represents his earlier career. Without a visual, one can surmise it would align with German Impressionism, perhaps featuring a figure in an interior setting, with an emphasis on the play of light from the window, a common motif for Impressionist painters like Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) or Max Liebermann (1847-1935). Such a work would highlight his skills in composition, color, and the depiction of atmosphere.

"Seated Youth" (Sculpture): This title suggests a classical theme, a subject favored by sculptors throughout history. In Kolbe's hands, a "Seated Youth" would likely embody the synthesis of Maillol's formal clarity and Rodin's surface vitality. One can imagine a figure with balanced proportions and a sense of quietude, characteristic of Maillol, but with a surface treatment that captures the subtle play of light, reflecting Rodin's influence. The youthfulness of the subject aligns with Kolbe's interest in idealized human forms, often conveying a sense of burgeoning life or contemplative grace. The specific dating of this piece to 1630 in some sources is clearly an error, given Kolbe's lifespan (1876-1945); it would undoubtedly be a 20th-century creation.

"Rhythmic Nudes" (Sculptures): This description points to a series or a recurring theme in Kolbe's sculptural oeuvre. The term "rhythmic" suggests an emphasis on flowing lines, harmonious movement, and a graceful articulation of the human body. These nudes would likely showcase his signature blend: the underlying structure and simplified volumes reminiscent of Maillol, animated by a dynamic surface texture that engages with light, a nod to Rodin. The focus on rhythm implies a concern with the musicality of form, a quality sought by many modern artists, including sculptors like Wilhelm Lehmbruck (1881-1919), whose elongated figures also possess a profound lyrical quality.

"Idealized Nordic Figures" (Sculptures, 1930s): Created in the 1930s, these works reflect a trend prevalent in Germany during that period, which saw a resurgence of interest in classical and heroic forms, often with a nationalist undertone. Kolbe's "Idealized Nordic Figures" would have adhered to this classical tradition in their subject matter and perhaps in their heroic portrayal. However, even within this context, his established artistic style – the fusion of Maillol's formalism and Rodin's surface treatment – would have been evident. These figures, while idealized, would likely still bear the hallmarks of his sensitive modeling and attention to light, distinguishing them from more rigidly academic or propagandistic works of the era. It's important to consider these works within the complex socio-political climate of 1930s Germany, a period that saw artists like Ernst Barlach (1870-1938) and Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945) face persecution for their "degenerate" art, while others navigated the pressures to conform to officially sanctioned aesthetics.

Kolbe in the Context of His Time: Contemporaries and Movements

Ernst Kolbe was active during a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Germany and across Europe. He was a contemporary of many artists who shaped the course of modern art. In Germany, the early 20th century saw the rise of Expressionism with groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), including Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1938), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (1884-1976), Erich Heckel (1883-1970), and Emil Nolde (1867-1956), and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) with Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) and Franz Marc (1880-1916). While Kolbe's style was more aligned with Impressionism and a modern classicism, he operated within this dynamic environment.

His involvement with the Berlin Artists' Association placed him within a network of established artists. Furthermore, the mention of his connection with figures like Max Beckmann (1884-1950), Renée Sintenis (1888-1965), Ernst Barlach, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff through "secessionist associations" is significant. Secession movements were a crucial feature of the art world at the turn of the century. The Vienna Secession (founded 1897), famously led by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) and including artists like Egon Schiele (1890-1918) and Oskar Kokoschka (1886-1980), sought to break away from the conservative, academic art establishment, promote modern art, and create new exhibition opportunities.

Similarly, Germany had its own Secessions. The Munich Secession was founded in 1892, and the Berlin Secession, founded in 1898, became particularly influential. Key figures of the Berlin Secession included Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth (1858-1925), and Max Slevogt (1868-1932), who championed Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in Germany. If Kolbe was associated with such groups, it indicates his alignment with progressive artistic tendencies and a desire to exhibit outside the confines of the traditional Salon system. His interaction with artists like Beckmann, a powerful figurative painter who would later become a key figure of New Objectivity, Sintenis, known for her delicate animal sculptures, the profoundly spiritual sculptor and printmaker Barlach, and the Brücke expressionist Schmidt-Rottluff, suggests a rich and diverse artistic dialogue.

It is also important to distinguish Ernst Kolbe from another prominent German sculptor of the same surname, Georg Kolbe (1877-1947). Georg Kolbe was a leading sculptor known for his lyrical and often athletic nudes, also influenced by Rodin and Maillol, and his work often overshadows that of Ernst. While they were contemporaries and shared similar artistic influences, they were distinct individuals.

The Broader European Art Scene and Kolbe's Place

Beyond Germany, the European art scene was undergoing radical changes. The legacy of Impressionism, with pioneers like Monet, Renoir, Edgar Degas (1834-1917), and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), had paved the way for Post-Impressionism, with artists like Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) pushing the boundaries of form, color, and expression.

In sculpture, Rodin remained a towering figure, influencing generations. His studio attracted artists from across the globe, and his expressive realism was a departure point for many. Camille Claudel (1864-1943), his gifted collaborator and an important sculptor in her own right, also contributed to this dynamic period. Maillol, as discussed, offered a more classical, serene alternative, influencing a lineage of sculptors who sought harmony and monumental simplicity.

The early 20th century also saw the rise of Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse (1869-1954), and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) and Georges Braque (1882-1963). These movements fundamentally challenged traditional notions of representation. While Ernst Kolbe's work did not directly engage with the radical abstraction of Cubism or the intense color of Fauvism, he was part of an era where the very definition of art was being reshaped. His work, bridging 19th-century sensibilities (Impressionism, Rodin's expressive realism) with early 20th-century concerns (Maillol's modern classicism), can be seen as part of this broader transition.

The assertion that artists like Matisse and Picasso were "fathers of us all" speaks to their immense impact on subsequent generations. Kolbe, working alongside these developments, carved out his own niche, focusing on a more lyrical and harmonious interpretation of the human form, grounded in observation but refined through a modern classical lens. His art represents a path that valued continuity with tradition while embracing contemporary modes of expression.

Legacy and Conclusion

Ernst Kolbe passed away in 1945, a year that marked the end of World War II and a profound rupture in European history and culture. His career spanned the dynamic late Wilhelmine era, the tumultuous Weimar Republic, and the dark years of the Nazi regime. Throughout these changes, he remained dedicated to his artistic vision, primarily focusing on the human figure.

His legacy is that of an artist who skillfully synthesized key sculptural influences of his time – the expressive dynamism of Rodin and the serene formalism of Maillol – while retaining a painter's sensitivity to light and surface. His work, characterized by idealized nudes and youthful figures, often exudes a gentle and elegant spirit, offering a counterpoint to the more angst-ridden or radically experimental art of some of his contemporaries.

While perhaps not as widely celebrated as some other German artists of his generation, Ernst Kolbe's contribution lies in his consistent exploration of a modern classicism, his ability to imbue traditional subjects with a subtle modernity through his distinctive handling of form and surface. He represents an important strand in early 20th-century German sculpture, one that valued craftsmanship, harmony, and a nuanced understanding of the human form. His journey from an Impressionist painter to a sculptor who forged a personal style from the titans of modern sculpture makes him a fascinating figure for those interested in the rich and varied artistic landscape of a transformative era. His art serves as a reminder that innovation can also be found in the thoughtful synthesis and personal interpretation of established traditions, bridging the past with the evolving present.