József Nemes Lamperth (1891–1924) stands as a significant, albeit tragically short-lived, figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century Hungarian and European art. A painter of formidable talent and intense vision, he was a key contributor to the Hungarian Expressionist movement, leaving behind a body of work characterized by its emotional depth, bold use of color, and dynamic brushwork. Though his career was cut short by his early death, his paintings resonate with the turbulent spirit of his era and showcase a profound engagement with the avant-garde currents sweeping across Europe.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Budapest in 1891, József Nemes Lamperth emerged during a period of immense cultural and artistic ferment in Hungary. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, though nearing its end, was a crucible of intellectual and creative activity. Budapest, in particular, was rapidly modernizing and becoming a significant European cultural capital. It was in this environment that Nemes Lamperth's artistic inclinations began to take shape. While specific details about his earliest artistic training are not extensively documented, it is known that he was part of a generation of young Hungarian artists eager to break away from the entrenched academic traditions that still dominated official art institutions.

A pivotal experience for many Hungarian artists of this period, including Nemes Lamperth, was their association with the Nagybánya artists' colony. Founded in 1896 by Simon Hollósy, Károly Ferenczy, István Réti, János Thorma, and Béla Iványi-Grünwald, Nagybánya (now Baia Mare, Romania) became a vital center for plein-air painting and the introduction of modern Western European artistic trends, particularly Post-Impressionism, into Hungary. While Nemes Lamperth's direct involvement timeline with Nagybánya is part of his broader development, the colony's emphasis on direct observation of nature, individual expression, and a departure from studio-bound academicism undoubtedly influenced the trajectory of Hungarian modernism and, by extension, artists like Nemes Lamperth.

The Hungarian Avant-Garde Context

To fully appreciate Nemes Lamperth's contribution, it's essential to understand the dynamic avant-garde scene in Hungary. Before and during his active years, groups like "The Eight" (Nyolcak), active from 1909 to 1918, had already begun to challenge artistic conventions. Members such as Róbert Berény, Dezső Czigány, Béla Czóbel, Károly Kernstok, Ödön Márffy, Dezső Orbán, Bertalan Pólya, and Lajos Tihanyi, were inspired by French Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism, as well as German Expressionism. They sought a new, modern Hungarian art that was both internationally aware and rooted in local sensibilities.

Following "The Eight," the "Activists" (Aktivisták), a literary and artistic movement centered around Lajos Kassák and his journal "A Tett" (The Deed, 1915-1916) and later "Ma" (Today, 1916-1925), became a dominant force. Nemes Lamperth was closely associated with the "Ma" circle. This group was more radical, embracing Expressionism, Cubism, Futurism, and Constructivism, and often imbued their art with strong social and political messages, particularly in the lead-up to and during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919. Artists like Béla Uitz and Sándor Bortnyik were prominent figures alongside Kassák in this movement. Nemes Lamperth's work from this period reflects this activist spirit and a desire to use art as a tool for social commentary and emotional expression.

Nemes Lamperth's Artistic Style: Color, Emotion, and Form

Nemes Lamperth's style is quintessentially Expressionist. He utilized color not merely for descriptive purposes but as a vehicle for conveying intense emotion and subjective experience. His palette is often characterized by strong, sometimes non-naturalistic hues, applied with vigorous, visible brushstrokes that imbue his canvases with a sense of energy and immediacy. This bold handling of paint and color aligns him with the broader European Expressionist tendencies seen in the works of German groups like Die Brücke (The Bridge), whose members included Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), with artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc.

His compositions often feature a dynamic interplay of forms, sometimes simplified or distorted to heighten their expressive impact. There's a raw, almost primal energy in his work, a departure from the more lyrical or decorative tendencies of some of his contemporaries. He sought to capture the essence of his subjects, whether landscapes, portraits, or nudes, filtering them through his own passionate temperament. This approach was a conscious rebellion against the polished surfaces and idealized representations favored by the academic art establishment of both Hungary and the influential Munich school.

A sense of drama and psychological intensity pervades his paintings. Even in his landscapes, there's often an underlying tension or a brooding quality, achieved through stark contrasts of light and shadow, and the forceful application of paint. His figures, when present, are rarely passive; they are imbued with an inner life and emotional weight that commands the viewer's attention.

Pivotal Works and Their Significance

Several key works exemplify Nemes Lamperth's artistic vision and his contribution to Hungarian Expressionism.

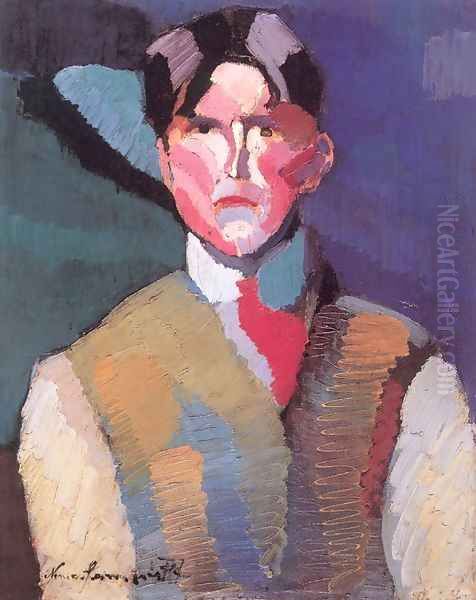

His _Self-portrait_ from 1911 is an early yet powerful declaration of his artistic identity. In it, one can already discern the intense gaze and bold handling of paint that would become hallmarks of his style. The work likely reflects a young artist grappling with his place in the world and the expressive potential of his medium.

_Tabán_ (1910) depicts a historic, somewhat bohemian district of Budapest that was later largely demolished. Such urban landscapes were popular subjects for modern artists, offering opportunities to explore the changing face of the city and the lives of its inhabitants. Nemes Lamperth's interpretation would have focused on the atmosphere and character of the place, rendered with his characteristic expressive force.

_Magyar: Háttáló női akt_ (Standing Female Nude), also known as Nude with Back Turned, from 1916, is a striking example of his figure painting. Expressionist nudes often departed from classical ideals of beauty, instead emphasizing raw emotion, vulnerability, or a sense of primal energy. Nemes Lamperth's treatment of the female form in this work would have been bold and unconventional for its time, focusing on expressive line and color rather than anatomical precision.

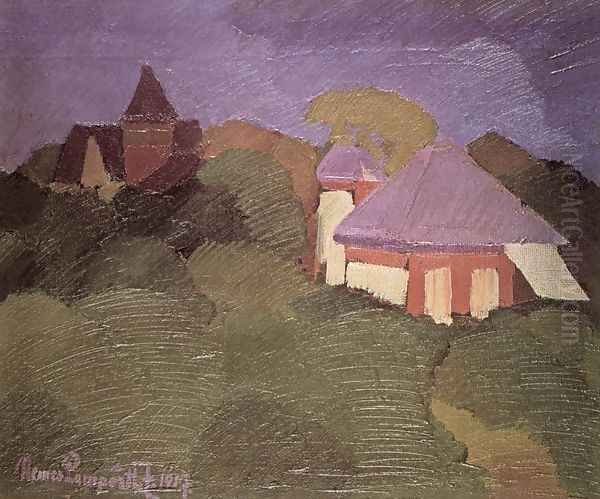

The year 1917 was particularly productive. _A Villa among Trees_ (62 cm × 75 cm) showcases his ability to transform a seemingly conventional subject into a vibrant, emotionally charged scene. The trees and villa are not merely depicted but are animated by the artist's energetic brushwork and heightened color, conveying a sense of nature's dynamism and perhaps the artist's own emotional state.

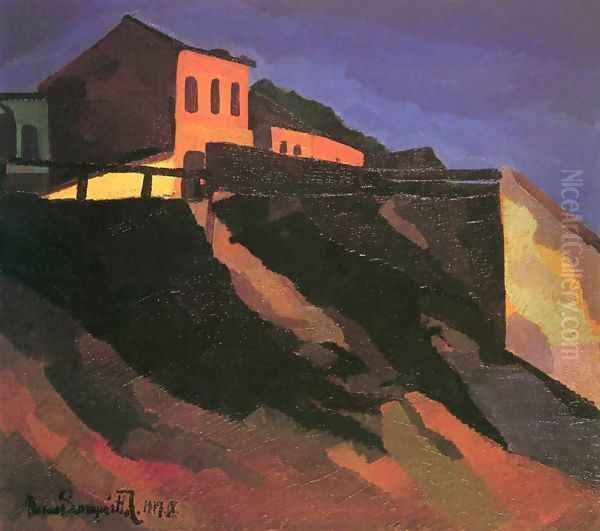

Perhaps one of his most celebrated works from this period is _On the Slopes of Gellért Hill_ (1917, 98.5 cm × 106 cm). Gellért Hill is a prominent landmark in Budapest, and Nemes Lamperth's rendition is far from a picturesque postcard. Instead, he imbues the landscape with a dramatic intensity, using powerful, gestural strokes and a rich, often somber palette to convey the raw beauty and underlying forces of nature. The forms of the landscape are simplified and monumentalized, reflecting an inner vision rather than a literal transcription.

Another significant landscape from this time is _Landscape (Landscape of Horgony Street)_ (1917). This piece further demonstrates his mastery of expressive landscape painting, where the depiction of a specific place becomes a conduit for broader emotional and formal explorations. The use of strong contrasts and abstracted forms is particularly evident, pushing the boundaries of representation towards a more subjective interpretation of reality.

His _Plant Still-life_ (1910-1911) shows his early engagement with expressive forms even in the still-life genre. The focus would be less on meticulous detail and more on the vitality and structural essence of the plants, rendered with bold colors and brushwork.

These works, housed in institutions like the Hungarian National Gallery, demonstrate Nemes Lamperth's commitment to an art that was deeply personal yet resonated with the wider avant-garde movements of his time. He sought to express not just the visible world, but the emotional and psychological realities that lay beneath the surface.

The "Ma" Group and Political Dimensions

Nemes Lamperth's involvement with Lajos Kassák's "Ma" group was crucial. "Ma" was more than just an art journal; it was a platform for radical artistic and social ideas. The artists associated with "Ma," including Nemes Lamperth, Róbert Berény (who had earlier been part of "The Eight"), Béla Uitz, and Sándor Bortnyik, were at the forefront of the Hungarian avant-garde. They embraced international styles like German Expressionism, French Cubism (as seen in the works of Picasso and Braque), and Italian Futurism (Marinetti, Boccioni), adapting them to a Hungarian context.

During the turbulent period of World War I and its aftermath, which included the Aster Revolution and the Hungarian Soviet Republic of 1919, "Ma" artists often engaged in creating political posters. These works were characterized by their bold, simplified forms, strong colors, and direct messaging, designed to communicate effectively with a mass audience. Nemes Lamperth participated in this aspect of the "Ma" group's activities, contributing to an art that was socially engaged and sought to play a role in shaping public consciousness. His work, like that of his "Ma" colleagues, often reflected a dissatisfaction with the existing social and political order and a desire for radical change. The use of distorted and abstract forms in their posters was sometimes a point of contention, sparking debates about the accessibility of avant-garde art for propaganda purposes.

International Exposure and Influences

Like many ambitious artists of his generation, Nemes Lamperth sought exposure to the artistic developments happening beyond Hungary's borders. Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, was a magnet for artists from across Europe. Nemes Lamperth spent time in Paris, where he would have encountered firsthand the revolutionary works of Fauvism, led by Henri Matisse and André Derain, with their explosive use of color, and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which deconstructed form and perspective. He is noted to have co-founded a modern art group in Paris, modeling it on German Expressionist principles, further highlighting his international outlook. His French given name, Joseph de Nemes, also suggests his engagement with the Parisian art scene.

German Expressionism was another profound influence. The raw emotional intensity, the bold distortions of form, and the vibrant, often clashing colors of groups like Die Brücke (Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff) and Der Blaue Reiter (Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc, August Macke) resonated deeply with Nemes Lamperth's own artistic temperament. These movements provided a powerful precedent for an art that prioritized subjective experience and emotional expression over objective representation.

Later Years and Tragic End

The period following World War I and the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic was a difficult one for many avant-garde artists in Hungary. The rise of a more conservative regime led to a less tolerant atmosphere for radical art. Many artists, including Lajos Kassák, emigrated. Nemes Lamperth's own career, so full of promise, was tragically cut short. He died in 1924 at the young age of 33. The exact circumstances of his later years and death are not as widely detailed as his artistic achievements, but his premature passing undoubtedly deprived Hungarian and European art of a unique and powerful voice.

Despite his short life, Nemes Lamperth's impact was significant. He was a vital part of a generation that transformed Hungarian art, bringing it into dialogue with the most advanced international movements. His work stands as a testament to the power of Expressionism to convey profound human emotion and to challenge conventional ways of seeing the world. The fact that his name appeared on a 1929 painting by a certain James Bailey, five years after his death, is an intriguing footnote, possibly suggesting a posthumous influence or a reinterpretation of his work by a later artist, though more details on this connection are scarce.

Legacy and Collections

József Nemes Lamperth's works are primarily held in Hungarian collections, with the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest housing a significant number of his key paintings. This ensures that his contribution to Hungarian art history is preserved and accessible. While specific auction records are not readily available in generalized summaries, his status as a leading Hungarian Expressionist means his works would be of considerable interest to collectors of Central European avant-garde art.

His legacy lies in his fearless embrace of modernism and his ability to forge a distinctive Expressionist style that was both deeply personal and reflective of the turbulent spirit of his times. He, along with contemporaries like Lajos Tihanyi, Béla Czóbel, and Vilmos Perlrott-Csaba (who also had strong connections to Paris and Nagybánya), helped to define a particularly Hungarian variant of Expressionism, characterized by its robust energy and rich colorism. He remains an important figure for understanding the dynamism of the Hungarian avant-garde and its connections to broader European artistic currents in the early 20th century. His art continues to speak to us today with its raw emotional power and its bold, uncompromising vision.