Ethel Carrick Fox stands as a significant figure in early 20th-century art, a British-born painter whose vibrant canvases captured the light and life of Europe, North Africa, and Australia. Celebrated for her bold use of colour and dynamic compositions, she navigated the art world with a characteristic independence and adventurous spirit. While often associated with her husband, the renowned Australian artist Emanuel Phillips Fox, Carrick Fox forged her own distinct path, contributing significantly to the development of Post-Impressionism, particularly within the Australian context. Her life and work offer a fascinating glimpse into the experiences of a modern female artist challenging conventions and seeking artistic expression across continents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born Ethel Carrick on February 7, 1872, in Uxbridge, Middlesex, England, she was the second of ten children born to Albert William Carrick, a prosperous draper, and Emma (née Filmer) Carrick. Growing up in a large Victorian family provided a conventional backdrop, yet Ethel harboured ambitions that diverged from the expected path for women of her time. Instead of settling into domestic life and marriage, she felt a strong calling towards a career in the arts, a decision that marked her as an independent thinker from an early age.

Her formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art in London, which she entered around 1888-1889. The Slade, under the influential directorship of figures like Alphonse Legros and later Fred Brown, was relatively progressive for its era, admitting female students and allowing them to work alongside their male counterparts, albeit sometimes with restrictions. Here, Carrick studied under notable teachers including the formidable draughtsman Henry Tonks, whose emphasis on structure and observation would have provided a solid foundation.

During her time at the Slade and in the following years, Carrick embraced the burgeoning trend of plein air painting – the practice of working outdoors directly from the subject. This approach was crucial for capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere that became central to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. She is known to have received guidance in this technique from Francis Bate, a proponent of the New English Art Club aesthetic, which championed French-influenced naturalism and Impressionistic methods over the more staid academic traditions.

Further immersing herself in modern painting techniques, Carrick spent time in artists' colonies, including St Ives in Cornwall. This coastal town was a magnet for artists drawn to its picturesque scenery and unique maritime light. Here, painters like Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley of the Newlyn School were already established, focusing on realist depictions of local life, often painted outdoors. While Carrick's later style would lean more towards Post-Impressionism, the experience in Cornwall undoubtedly sharpened her skills in capturing light and observing everyday scenes, and crucially, it was here her life would take a decisive turn.

Encounter in St Ives and Partnership in Paris

It was within the vibrant artistic community of St Ives, around 1903, that Ethel Carrick met Emanuel Phillips Fox (commonly known as E. Phillips Fox). He was an established Australian painter, trained in Melbourne under G. F. Folingsby at the National Gallery School and later in Paris at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts under masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau. Fox had already achieved considerable success in Europe, particularly at the Paris Salons.

Despite E. Phillips Fox being Jewish and Carrick likely Anglican, and the societal norms of the time, they found common ground in their shared passion for art and modern painting techniques. Their connection deepened, and they married in London on May 9, 1905. Following their marriage, they made Paris their primary base. This move placed Ethel Carrick Fox at the very heart of the European art world during a period of intense innovation and experimentation.

Paris was the undisputed centre of modern art. The legacy of Impressionism, pioneered by artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Edgar Degas, was pervasive. However, new movements were constantly emerging. Post-Impressionist ideas, exploring subjective colour, form, and emotion, were gaining traction through the work of artists like Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. Fauvism, with its explosive, non-naturalistic colour, was about to burst onto the scene led by Henri Matisse and André Derain.

Living and working in this stimulating environment profoundly influenced Carrick Fox's artistic development. While her husband was already well-integrated into the Parisian art scene, exhibiting regularly at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (the New Salon), Ethel quickly established her own presence. E. Phillips Fox was supportive of her career, and they often worked alongside each other, travelling and painting together, yet Ethel maintained her distinct artistic voice.

Post-Impressionist Sensibilities: Colour, Light, and Life

Ethel Carrick Fox's mature style is best characterized as Post-Impressionist, marked by a heightened sensitivity to colour and light, applied with vibrant energy. While clearly absorbing lessons from Impressionism regarding the capture of fleeting moments and atmospheric effects, she moved beyond its purely optical concerns. Her work embraces the more subjective and decorative potential of colour, aligning her with French modernists like Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and Maurice Denis, whose works she would have seen in Paris galleries and exhibitions.

Her palette became brighter and more daring than that of many of her contemporaries. She employed high-keyed colours, often juxtaposing complementary tones to create shimmering, vibrant surfaces. Brushwork was typically loose and expressive, applied in distinct dabs or strokes that contribute to the overall texture and liveliness of the painting. She wasn't afraid to use strong outlines or flattened perspectives where it served the composition, demonstrating a move away from strict naturalism towards a more decorative and emotionally resonant depiction.

Carrick Fox excelled at capturing the bustle and energy of modern life. Her favoured subjects included crowded market scenes, sunny beaches, parks filled with strolling figures, outdoor cafes, and flower stalls. Unlike the more intimate domestic interiors favoured by artists like Vuillard, Carrick Fox often focused on public spaces, revelling in the patterns created by crowds, the play of sunlight and shadow across diverse surfaces, and the inherent joie de vivre of these communal moments. Her paintings are rarely melancholic; instead, they radiate warmth, optimism, and a delight in the visual spectacle of the everyday world.

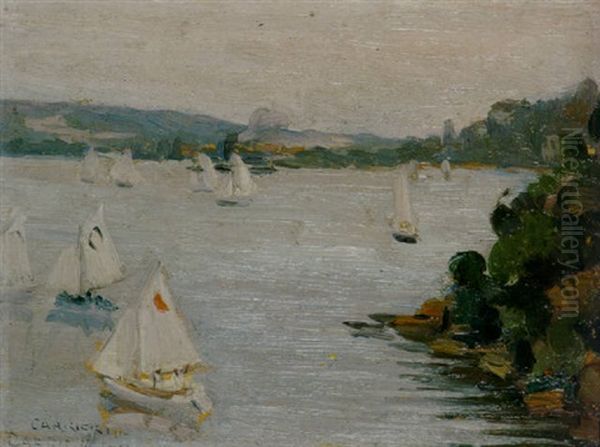

The practice of plein air painting remained fundamental to her approach. Many of her works, particularly smaller panels, have the immediacy and freshness of studies executed directly on the spot. These sketches often served as basis for larger, more finished compositions completed in the studio, but they retained the spontaneity and authentic light effects captured outdoors. This commitment to direct observation, combined with her sophisticated understanding of colour theory, resulted in works that feel both immediate and thoughtfully constructed.

Exhibitions, Travels, and Key Works

Throughout her career, Ethel Carrick Fox actively exhibited her work in prestigious venues across Europe and Australia. She became a regular exhibitor at the Salon d'Automne in Paris, a progressive alternative to the more established Salons, known for showcasing avant-garde art. She also showed work at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, alongside her husband, and participated in exhibitions in London, including those of the Royal Academy (though less frequently). Her involvement with the International Union of Women Painters further highlights her engagement with the professional networks available to female artists.

Her travels provided a rich source of inspiration and subject matter. The couple made extended visits to Australia in 1908 and 1913, where Ethel exhibited her work, introducing many Australian viewers to a more modern, Post-Impressionist style. Her painting Esquisse en Australie (c. 1908) is significant as an early example of her work shown Down Under, demonstrating her advanced European sensibilities. These visits were important for disseminating modern art ideas in Australia, contributing to a shift away from the more tonal Heidelberg School style associated with artists like Arthur Streeton and Tom Roberts.

Journeys to North Africa, including Algeria and Morocco, resulted in paintings filled with exotic colour and light, depicting bustling souks, marketplaces, and sun-drenched landscapes. These works showcase her ability to adapt her palette and technique to capture different environments and cultural settings, adding another dimension to her oeuvre. She continued to travel extensively even after her husband's untimely death in 1915.

Among her most celebrated works is The Market (c. 1919, though sometimes dated earlier). This painting exemplifies her mature style: a vibrant depiction of a crowded outdoor market, rendered in high-keyed Impressionist and Post-Impressionist colours. The composition is dynamic, filled with figures suggested through deft brushstrokes, and the interplay of bright sunlight and cool shadows is masterfully handled. It is considered a key work not only in her career but also in the broader context of Australian art history, representing a confident embrace of modern European aesthetics.

Another notable work often discussed is French Flower Market (various versions exist). One such painting achieved a record price for a work by an Australian woman artist when sold at auction in 1996 for A5,500, signalling a growing appreciation for her contribution. These market scenes, recurring motifs in her work, allowed her to explore complex compositions, diverse textures, and, above all, the expressive power of colour.

The "New Woman" in Art and Society

Ethel Carrick Fox embodied many characteristics of the "New Woman" – a term used in the late 19th and early 20th centuries to describe women who sought independence, education, and professional careers, challenging traditional gender roles. Her decision to pursue art seriously, foregoing the expected path of marriage and domesticity until she met a partner who shared her artistic devotion, was a significant assertion of autonomy.

Even after marriage, she maintained her professional identity. While E. Phillips Fox was undoubtedly the more famous artist during their lifetime together, Ethel continued to develop her own style, exhibit under her own name (often as Ethel Carrick or E. Carrick Fox), and build her own reputation. This partnership, seemingly one of mutual artistic respect, was nonetheless subject to the societal pressures of the time. Sources suggest that E. Phillips Fox's family sometimes expressed disapproval of her dedication to her career over starting a family.

Her independence extended beyond her artistic practice. During World War I, after her husband's death from cancer in Melbourne in 1915, Ethel remained active and engaged. She worked with the Red Cross in France, supporting the efforts to aid prisoners of war and refugees. This commitment to humanitarian causes reflects a broader social conscience often associated with progressive women of her era. She continued to exhibit her work in progressive galleries in both Sydney and Paris, maintaining her professional life despite personal loss and the upheaval of war.

However, navigating the art world as a woman, even one as determined as Carrick Fox, presented unique challenges. Her work was sometimes overshadowed by her husband's greater fame. There are anecdotal accounts of dealers potentially misattributing unsigned works found in their shared studio to E. Phillips Fox, believing his name would command a higher price. This highlights the systemic biases that often undervalued the contributions of female artists.

Furthermore, her practice of signing her works in various ways ("Carrick," "E. Carrick," "Ethel Carrick," "E. Carrick Fox") and occasionally giving different titles or dates to similar scenes has sometimes created complexities for art historians and the market. While not uncommon among artists who revisited subjects or prepared works for different exhibitions, it adds a layer of difficulty to definitively cataloguing her output.

Later Life, Legacy, and Recognition

After E. Phillips Fox's death, Ethel spent much of her time promoting his work and legacy, organizing memorial exhibitions. However, she continued her own painting and extensive travels, visiting India and later returning to Australia. She remained an active artist, though perhaps less prolific in her later years. She eventually settled back in Melbourne, where she passed away on June 17, 1952, at the age of 80.

In the decades following her death, Ethel Carrick Fox's reputation has steadily grown. Initially often mentioned primarily as the wife of E. Phillips Fox, critical reassessment, particularly fueled by feminist art history from the 1970s onwards, has increasingly recognized her distinct artistic achievements and her significance as a pioneer of modernism in Australia. Critics now often praise the vibrancy, boldness, and adventurous spirit of her work, sometimes suggesting her style was, in certain respects, more forward-looking than her husband's.

Her paintings are held in major public collections across Australia, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and the Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), as well as in numerous private collections. Her works continue to be sought after at auction, achieving strong prices that reflect her established importance.

Ethel Carrick Fox's legacy lies in her vibrant contribution to Post-Impressionist painting, particularly her masterful use of colour and light to capture the energy of modern life. She stands as an important link between European modernism and Australian art, helping to introduce and popularize progressive styles Down Under. Moreover, her life story serves as an inspiring example of a determined female artist who pursued her vision with independence and passion, overcoming societal constraints to create a significant body of work that continues to delight and engage viewers today. Her art remains a testament to a life lived fully, embracing colour, travel, and the dynamic beauty of the world around her.