Introduction: An Artist of Le Havre and Paris

Emile-Othon Friesz stands as a significant figure in the vibrant landscape of early 20th-century French art. Born in the bustling port city of Le Havre on February 6, 1879, and passing away in Paris on January 10, 1949, Friesz's life spanned a period of radical artistic transformation. Primarily associated with the Fauvist movement, his artistic journey was one of exploration, evolution, and a unique dialogue between revolutionary modernism and enduring tradition. He navigated the currents of Impressionism, plunged into the chromatic intensity of Fauvism, and later forged a path back towards a more structured, classical approach, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Le Havre

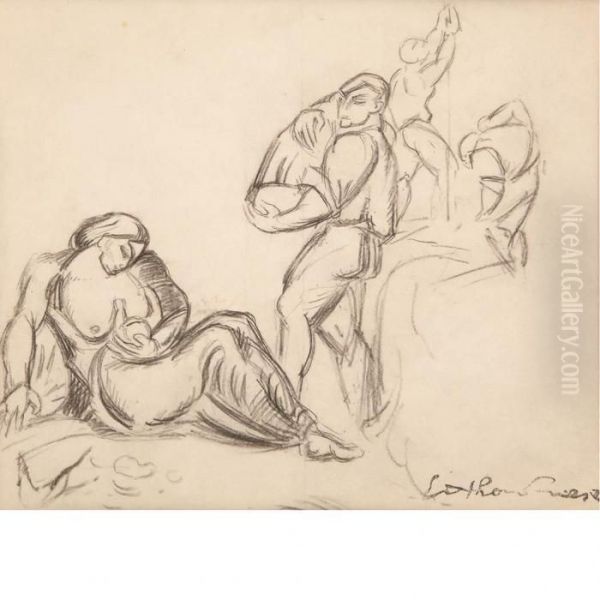

Friesz's artistic inclinations emerged early in his hometown of Le Havre, a city whose maritime atmosphere and lively docks would later feature in his work. His family, involved in the seafaring trade, provided a backdrop connected to the wider world. Crucially, he enrolled at the École Municipale des Beaux-Arts in Le Havre around 1895. Here, he received formal training under Charles Lhuillier, a respected local painter. Lhuillier's instruction provided Friesz with a solid foundation in drawing and traditional techniques, skills he would later revisit and integrate into his mature style.

Perhaps equally important during this formative period were the friendships Friesz forged at the Le Havre school. He became close companions with Raoul Dufy and Georges Braque. These young artists shared aspirations and undoubtedly stimulated each other's development. While Braque would later co-found Cubism with Pablo Picasso, and Dufy would develop his own distinctively light and decorative style, their early association with Friesz in Le Havre marked the beginning of significant careers intertwined with the course of modern art. This shared starting point highlights the fertile artistic environment of provincial France at the turn of the century.

Arrival in Paris and Impressionist Influences

Around 1899, fueled by ambition and encouraged by a municipal scholarship, Friesz moved to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world. He furthered his studies at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, entering the studio of the academic painter Léon Bonnat. However, like many aspiring modernists of his generation, Friesz found the conservative academic training less compelling than the revolutionary art movements unfolding outside the institution's walls.

Initially, Friesz gravitated towards Impressionism, the dominant avant-garde style of the preceding decades. He admired the work of artists like Camille Pissarro and Auguste Renoir, drawn to their focus on light, atmosphere, and capturing fleeting moments. His early works from this period reflect this influence, employing broken brushwork and a relatively naturalistic palette to depict landscapes and scenes of daily life. He began exhibiting his work, showing for the first time at the Salon des Artistes Français in 1900.

Despite these early steps, Friesz, like his contemporaries, soon felt the limitations of Impressionism. The turn of the century was a time of intense artistic searching, with artists seeking more personal and expressive means of representation. The subjective experiences and emotional responses to the world began to take precedence over purely optical sensations, paving the way for the next major upheaval in French painting. Friesz's engagement with Impressionism was thus a crucial, but transitional, phase in his development.

The Fauvist Revolution: Color Unleashed

The pivotal moment arrived around 1904-1905. Friesz, along with a group of like-minded painters, began experimenting with a radically different approach to color and form. This coalesced into the movement known as Fauvism, famously christened by the critic Louis Vauxcelles at the Salon d'Automne of 1905. Vauxcelles, struck by the intense, non-naturalistic colors and bold execution of works by Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, and others displayed near a traditional sculpture, exclaimed it was like "Donatello au milieu des fauves" (Donatello among the wild beasts).

Friesz was a key participant in this "wild beast" revolution. Although perhaps not in the specific room that provoked Vauxcelles' comment, he exhibited alongside the core Fauves at the Salon d'Automne and the Salon des Indépendants during these crucial years. Fauvism was characterized by its liberation of color from descriptive duty; hues were chosen for their emotional impact and compositional strength rather than their adherence to reality. Brushwork became energetic and expressive, forms were simplified, and perspective often flattened, creating canvases that pulsed with raw energy and feeling.

Friesz fully embraced this new aesthetic. He abandoned the subtleties of Impressionism for vibrant, often clashing colors applied in broad strokes or patches. His subjects – landscapes, cityscapes, figures – were transformed through this intense chromatic lens. This period marked a definitive break from his earlier style and established him as a leading figure within the Fauvist group, contributing significantly to the movement's visual language and impact.

The Antwerp Trip: A Catalyst for Fauvist Expression

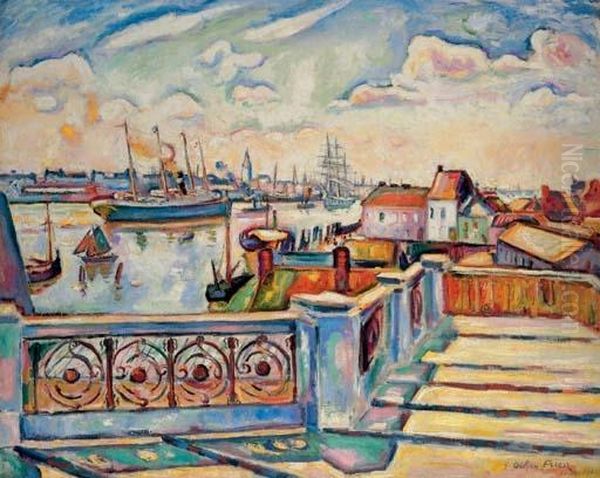

A particularly significant event in Friesz's Fauvist development occurred during the summer of 1906. He traveled to Antwerp, Belgium, in the company of his old friend Georges Braque. Raoul Dufy was also working nearby. This shared experience proved immensely stimulating. The bustling port city, with its vibrant maritime life, offered rich subject matter, but more importantly, the collaborative atmosphere and shared artistic goals pushed their Fauvist experiments forward.

Friesz's paintings from Antwerp are considered high points of his Fauvist period. Works like Le Port d'Anvers (The Port of Antwerp, 1906) exemplify the style. In this painting, the docks, ships, and water are rendered in bold, arbitrary colors – perhaps orange skies, green water, and purple buildings. The brushwork is vigorous and visible, conveying energy rather than precise detail. Composition is simplified, focusing on strong shapes and dynamic rhythms. The painting is less a depiction of Antwerp's physical appearance and more an expression of the artist's vibrant sensory and emotional response to the scene.

This trip solidified Friesz's commitment to Fauvism and demonstrated his mastery of its principles. The Antwerp works, alongside those produced by Braque during the same period, showcase the shared exploration of expressive color and form that defined the movement's peak. It was a moment of intense creativity and shared discovery among these young artists.

Peak Fauvism and Artistic Circles

Between 1905 and 1907, Friesz was deeply immersed in the Fauvist movement and its associated circles. He exhibited regularly at the key avant-garde venues: the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d'Automne. In 1907, his work was shown at the influential Galerie Berthe Weill and also at Galeries Druet, often alongside paintings by Matisse, Marquet, Dufy, Derain, and Vlaminck. This period saw the creation of some of his most celebrated Fauvist canvases.

His relationship with Henri Matisse, often considered the leader of the Fauves, was one of mutual respect. While perhaps not as intimate as Matisse's bond with Derain, Friesz clearly admired Matisse's groundbreaking use of color and participated in group exhibitions that highlighted the Fauvist collective. Friesz's work from this time, like Matisse's, often featured landscapes from the South of France (such as La Ciotat, where he worked with Braque) or Normandy, rendered with dazzling palettes.

Friesz also maintained close ties with Albert Marquet, another artist associated with Fauvism, known for his more subdued but equally modern depictions of Paris and port cities. Friesz, Marquet, Matisse, and others formed a dynamic group, sharing ideas, exhibiting together, and pushing the boundaries of painting. Works like Travail à l'automne (Work in Autumn, 1907) show Friesz's Fauvist style fully developed, using strong color contrasts and simplified forms to convey the energy of the landscape and figures. This period, though relatively brief for Fauvism as a cohesive movement, was incredibly fertile for Friesz.

Shifting Styles: Beyond Fauvism

Interestingly, even as Fauvism reached its zenith around 1907-1908, Friesz began to move away from its most radical aspects. While his Fauvist works were gaining recognition and even some commercial success, he started to reintroduce elements of structure and volume into his paintings. The intense, purely expressive color began to be tempered by a greater concern for form and composition.

This shift can be attributed to several factors. The influence of Paul Cézanne, whose posthumous retrospective in 1907 had a profound impact on many Parisian artists, was significant. Cézanne's emphasis on underlying geometric structures, solidity, and constructive brushwork offered an alternative to both Impressionist dissolution and Fauvist exuberance. Friesz, like his friend Braque (who was simultaneously moving towards Cubism with Picasso), felt the pull of Cézanne's quest for pictorial order.

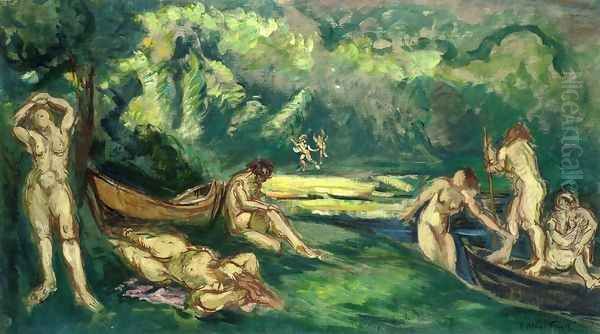

Friesz sought a way to integrate the Fauvist liberation of color with a more traditional sense of composition and drawing. His works from 1908 onwards show a gradual change: palettes become somewhat more subdued, though still rich; forms gain weight and definition; and there is a renewed interest in creating a sense of depth and space, albeit often through simplified planes rather than traditional perspective. This marked the beginning of a new phase, distinct from both his earlier Impressionism and his peak Fauvism.

Representative Works: A Stylistic Spectrum

Examining specific works highlights Friesz's evolution. Le Port d'Anvers (1906) remains a quintessential Fauvist piece, bursting with non-naturalistic color and energetic brushwork, capturing the raw vitality of the scene. Travail à l'automne (1907), exhibited at the Salon d'Automne, continues this Fauvist intensity, depicting figures in a landscape with bold color harmonies and simplified drawing, emphasizing rhythm and pattern.

Landscape with Figures (Paysage avec personnages), dated around 1909, potentially illustrates the transition away from pure Fauvism. While color might still be strong, there's often a greater sense of compositional structure and solidity in the forms compared to the Antwerp works. The figures might be more clearly delineated, and the landscape organized into more distinct planes, showing the growing influence of Cézanne.

A later work like Femme assise dans un jardins (Woman Sitting in a Garden) from 1923 showcases his mature style. Here, the Fauvist fire has cooled considerably. The colors are rich but more naturalistic and harmonized. The drawing is firm and clear, defining the figure and the surrounding garden elements with confidence. There is a sense of calm, order, and classical balance that contrasts sharply with the exuberance of his 1906-1907 period. This painting reflects his return to certain traditional values, filtered through his modernist experience. His output consistently included landscapes, still lifes, nudes, and portraits throughout these stylistic shifts.

Later Career: Consolidation and Teaching

The years leading up to and following World War I saw Friesz consolidating his artistic direction. Around 1912, he demonstrated his growing independence and stature by opening his own studio in Paris, where he not only worked but also began to teach. This teaching activity continued until the outbreak of war in 1914, when Friesz, like many of his generation, was mobilized for service.

His experiences during the war inevitably impacted his outlook and art. After demobilization, he returned to Paris and resumed his career. His style continued along the path established before the war – a synthesis of modern color sensibilities with a strong emphasis on drawing, composition, and a connection to the French classical tradition. He looked towards masters like Nicolas Poussin and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, seeking a timeless quality in his art.

His post-war work, while perhaps lacking the revolutionary fervor of his Fauvist years, was characterized by solid craftsmanship, balanced compositions, and a rich, often earthy palette. He continued to paint landscapes, particularly of Normandy and the South of France, as well as portraits and nudes. He exhibited regularly and gained steady recognition, becoming a respected figure in the Parisian art scene, distinct from the more radical paths being forged by Cubists or Surrealists.

Themes and Enduring Interests

Throughout his stylistic evolution, certain themes remained constant in Friesz's work. Landscape painting was a lifelong passion, from the early Impressionist views to the vibrant Fauvist scenes of Antwerp and La Ciotat, and the more structured, classical landscapes of his later years. He had a particular affinity for port cities, perhaps stemming from his Le Havre origins, and coastal scenes frequently appear in his oeuvre.

The human figure was also central, appearing in portraits, nudes, and genre scenes like Travail à l'automne. His approach to the figure evolved alongside his style, from the simplified, color-driven forms of Fauvism to the more solidly modeled figures of his later work. Still life provided another genre for exploring form and color, allowing for controlled compositional arrangements.

A key aspect mentioned in anecdotes about Friesz is his belief in the importance of direct contact with nature. Even as his style became more structured, he advocated for drawing inspiration directly from the observed world. This connection to nature, filtered through his artistic sensibility, remained a cornerstone of his practice, linking him to a long tradition of French landscape painting while incorporating the lessons of modernism.

Interactions with Contemporaries Revisited

Friesz's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships. His early bond with Dufy and Braque in Le Havre was foundational. In Paris, his participation in Fauvism placed him in close proximity to Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, and Marquet. While Braque took a different path towards Cubism with Picasso after their shared Fauvist phase, their early connection remained part of their individual histories.

His relationship with Matisse was significant during the Fauvist years, marked by shared exhibitions and a mutual engagement with expressive color. While Matisse continued to innovate in highly personal ways, Friesz chose a different route after 1908. His connection with Marquet, another artist who navigated Fauvism before developing a distinct, more tonal style, might represent a closer parallel in some respects.

Friesz also interacted with the broader Parisian art world, including dealers like Berthe Weill and Druet, and critics who followed his evolution. He was part of the generation that included figures like Kees van Dongen, another Fauve known for his society portraits, and was aware of the monumental shifts brought by Picasso and Cubism, even as he forged his own path. His later role as a teacher also brought him into contact with younger generations, such as the American modernist Edwin Frankish, who reportedly found inspiration in Friesz's circle.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Museum Collections

Friesz's work was consistently visible through exhibitions throughout his career. His participation in the Salon des Indépendants (from 1904) and the Salon d'Automne (from 1905) placed him at the heart of the avant-garde early on. Solo and group shows at prominent galleries like Galeries Druet and Galerie Berthe Weill cemented his reputation during the Fauvist period.

Even after his style shifted, he continued to exhibit regularly in Paris and internationally. His work entered major public collections during his lifetime and posthumously. The French state acquired works, including Femme assise dans un jardins, now housed in the collection of the Centre Pompidou (Musée National d'Art Moderne) in Paris.

Today, Friesz's paintings are held in numerous prestigious museums worldwide. These include the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the National Gallery in London, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, and many others across Europe and North America. This widespread institutional recognition underscores his lasting importance in the narrative of modern art.

Anecdotes and Artistic Philosophy

Anecdotes offer glimpses into Friesz's life and character. The story of his early, impoverished years living in a dilapidated house nicknamed "Les Hautes Folies" in Falaise, while striving to break free from Impressionism, highlights his determination and the challenging circumstances many artists faced. His commitment to working directly from nature, seeking inspiration outdoors, reflects a philosophy grounded in observation, even when transformed by Fauvist color or later classical structure.

His decision to open his own studio and teach suggests a degree of independence and a desire to pass on his knowledge. The shift away from pure Fauvism, while perhaps disappointing to those who championed the movement's initial radicalism, indicates an artist engaged in a serious, ongoing dialogue with tradition and his own evolving aesthetic goals. He sought a balance between modern expressiveness and enduring principles of composition and form.

Legacy and Conclusion: A Unique Path in Modernism

Emile-Othon Friesz occupies a distinct and important place in early 20th-century art. He was undeniably a key figure in the Fauvist movement, contributing significantly to its development with vibrant and powerful works created between roughly 1905 and 1907. His paintings from this period remain compelling examples of Fauvism's revolutionary use of color and expressive energy.

However, his artistic journey did not end there. His subsequent move towards a more structured, classically influenced style sets him apart from contemporaries like Matisse, who continued to explore color and decoration in highly innovative ways, or Braque and Picasso, who delved into the analytical and synthetic phases of Cubism. Friesz forged a more conservative modern path, seeking to reconcile the breakthroughs of Fauvism with the enduring traditions of French painting.

His legacy lies in both his contribution to Fauvism and his subsequent exploration of a modern classicism. He was a skilled draftsman and a sensitive colorist throughout his career. His works offer a fascinating case study of an artist navigating the complex currents of modernism, engaging deeply with its innovations while ultimately seeking a synthesis with historical principles. Emile-Othon Friesz remains a respected painter whose works continue to be admired in collections around the world, representing a significant chapter in the story of French art.