An Introduction to the Artist

Eugène Carrière stands as a distinctive figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century French art. Primarily associated with the Symbolist movement, he carved a unique niche for himself through a highly personal and instantly recognizable style. Born on January 16, 1849, in Gournay-sur-Marne, Seine-et-Marne, and passing away in Paris on March 27, 1906, Carrière's life spanned a period of significant artistic upheaval and innovation. He is most celebrated for his evocative, near-monochromatic paintings, typically rendered in swirling mists of brown, sepia, and grey, which lend his subjects an ethereal, dreamlike quality. His work predominantly explores intimate themes, particularly motherhood, family life, and the tender bonds between individuals, imbued with profound psychological depth and emotional resonance.

Carrière's approach was one of quiet intensity. He sought to look beyond mere surface appearance, using his signature hazy style to suggest the inner life and spiritual essence of his subjects. While contemporary with the Impressionists, his focus diverged significantly; instead of capturing fleeting moments of light and colour in the external world, Carrière delved into the enduring, often melancholic, atmosphere of domestic interiors and the universal experiences of love, loss, and connection. He was a painter of shadows, but within those shadows, he illuminated the subtle complexities of the human soul. His influence extended beyond his own canvases, touching prominent artists who would shape the course of modern art.

Formative Years and Artistic Awakening

Eugène Carrière's journey into the art world was not straightforward. His early training began not with painting, but with the craft of lithography in Strasbourg. This foundational experience likely instilled in him an appreciation for tonal values and the expressive potential of black and white, elements that would become central to his later painterly style. His time in Strasbourg was interrupted by the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), during which he served and was briefly taken prisoner in Dresden. Some accounts suggest that seeing works by Peter Paul Rubens during this period left a lasting impression on him, potentially influencing his later appreciation for dynamic forms and emotional intensity, albeit translated into his own subdued palette.

![Maternite [ ; Maternity; Signed And Dated Lower Right ; Oil On Canvas] by Eugene Carriere](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/1981909/m/eugene-carriere-maternite-maternity-signed-and-dated-lower-right-oil-on-canvas-9febbb1e.jpg)

Returning to France, Carrière resolved to pursue painting more seriously. In 1870, he gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the epicenter of academic art training. There, he entered the studio of Alexandre Cabanel, a highly respected and successful academic painter known for his polished historical and mythological scenes. Cabanel represented the established artistic order, and studying under him provided Carrière with a solid grounding in traditional techniques. However, Carrière's artistic temperament leaned away from the polished surfaces and historical grandeur favored by his master.

Despite some sources noting he was considered an unexceptional student in his youth, Carrière possessed a quiet determination and an unwavering commitment to his artistic vision. He was known for his persistence and dedication to drawing, filling countless pages with sketches and studies. This period was crucial for honing his skills and beginning the process of diverging from academic convention towards a more personal mode of expression. His early works still showed academic influences, but the seeds of his unique style were beginning to germinate, driven by his introspective nature and his focus on the intimate world around him.

The Emergence of a Unique Vision: The Monochrome Palette

The most striking aspect of Eugène Carrière's art is undoubtedly his distinctive use of colour, or rather, his deliberate restriction of it. By the 1880s, he had largely abandoned a full spectrum palette in favour of a near-monochromatic scheme dominated by shades of brown, ochre, grey, and sepia. This approach, often described as a form of grisaille or compared to the tonal qualities of old photographs or lithographs, became his trademark. His figures seem to emerge from and recede into a swirling, smoky mist, their forms defined more by subtle shifts in light and shadow (chiaroscuro) than by clear outlines or contrasting hues.

This stylistic choice was far from arbitrary; it was integral to the emotional and psychological impact of his work. The soft, hazy atmosphere, sometimes referred to as his "brouillard" (fog) or likened to Leonardo da Vinci's sfumato, creates a sense of intimacy and introspection. It dissolves the specificity of time and place, focusing instead on the universal and timeless quality of the emotions depicted. The limited palette forces the viewer to engage more deeply with the composition, the interplay of light, and the subtle expressions of the figures, enhancing the feeling of quiet contemplation and psychological depth.

Carrière's style is often linked to Symbolism, a movement that prioritized the expression of ideas, emotions, and subjective experience over objective reality. His misty visuals effectively convey a sense of mystery, memory, and the intangible bonds connecting his subjects. While sometimes superficially compared to Impressionism due to the soft focus, his aims were different. He wasn't capturing the fleeting effects of light but rather using light and shadow to sculpt form and evoke a sustained emotional mood, an "Impressionism of Mass" as some critics termed it, focusing on the weight and presence of figures within their atmospheric envelope. This unique visual language set him apart from his contemporaries and became the vehicle for his profound exploration of human relationships.

Themes of Intimacy: Motherhood, Family, and the Human Spirit

Central to Eugène Carrière's oeuvre are themes drawn from his own domestic life. He married Sophie Desmousseaux in 1877, and the couple eventually had seven children. His wife and children became his most frequent models, and the recurring motif of motherhood, or Maternité, is perhaps what he is best known for. These are not idealized or sentimentalized depictions; rather, they are profoundly tender and psychologically insightful portrayals of the intimate bond between mother and child. The figures often appear closely intertwined, their forms merging within the characteristic hazy atmosphere, visually reinforcing their emotional connection.

Carrière's focus on his own family allowed him to explore universal human experiences with authenticity and empathy. His paintings capture quiet moments of everyday life – a mother nursing her baby, children reading or sleeping, family members gathered together. Yet, through his distinctive style, these ordinary scenes are elevated to something more profound and symbolic. The enveloping shadows and soft light seem to protect the figures, creating a sanctuary of familial love while also hinting at the inherent vulnerability and mystery of human existence. The faces, often partially obscured or looking inward, convey a sense of contemplation and deep feeling.

Beyond his family, Carrière also painted portraits of friends and prominent figures within his intellectual and artistic circle. These portraits, rendered in the same signature style, similarly aimed to capture the inner essence rather than just a physical likeness. He painted fellow artists like Paul Gauguin, writers such as Alphonse Daudet and Paul Verlaine, and the influential politician Georges Clemenceau. In each case, the monochromatic palette and soft focus serve to emphasize the sitter's psychological presence and character. Through these intimate themes, whether familial or portraits of friends, Carrière consistently explored the depths of human connection, emotion, and the quiet dramas of the inner life.

Signature Works: Capturing Emotion in Shadow

Several works stand out as quintessential examples of Eugène Carrière's artistic vision and style. The Young Mother (Jeune mère) or Maternity (Maternité), variations of which he painted throughout his career, starting around 1879, is perhaps his most iconic theme. One early version, exhibited at the Salon, depicts his wife Sophie nursing their first child. Rendered in his developing monochromatic style, the figures emerge softly from a dark, undefined background. The focus is entirely on the tender interaction, the gentle curve of the mother's embrace, and the quiet absorption of the moment. The lack of distracting detail or bright colour intensifies the emotional impact, drawing the viewer into the intimate space shared by mother and child.

Another significant work is Christ on the Cross (Le Christ en Croix), painted around 1897. Applying his signature style to a traditional religious subject, Carrière creates a deeply moving and personal interpretation of the crucifixion. Christ's body is bathed in a soft, ethereal light, seeming almost to dissolve into the surrounding gloom. The emphasis is less on physical suffering and more on the spiritual and emotional weight of the moment. The characteristic misty atmosphere lends the scene a timeless, dreamlike quality, inviting contemplation rather than depicting graphic agony. This work demonstrates Carrière's ability to infuse even conventional subjects with his unique sensibility.

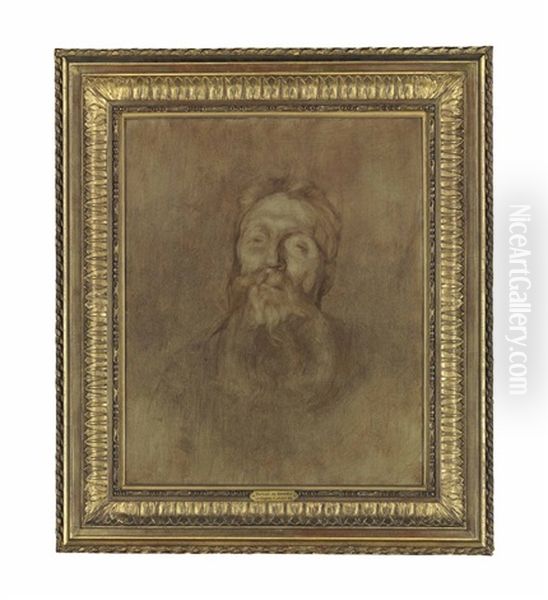

His portraits are also highly regarded. The Portrait de Paul Verlaine (c. 1890) captures the troubled intensity of the poet, his face emerging hauntingly from the shadows. Similarly, his portrait of the sculptor Auguste Rodin (a close friend) conveys a sense of powerful introspection. The Portrait de David, mentioned in the initial summaries, likely refers to one of his many portraits where the sitter's inner life is suggested through the interplay of light and shadow rather than sharp detail. These works, alongside numerous depictions of his own family, solidify Carrière's reputation as a master of psychological portraiture, using his limited palette to explore the nuances of human emotion and presence.

Beyond the Canvas: Carrière the Lithographer

While primarily known as a painter, Eugène Carrière was also a highly accomplished lithographer. His early training in Strasbourg provided him with a strong technical foundation in the medium, and he continued to create prints throughout his career. Importantly, his work in lithography was not separate from his painting practice but rather a parallel exploration of his core artistic concerns, executed in a medium naturally suited to his aesthetic.

Carrière's lithographs closely mirror the style and themes of his paintings. They are characterized by the same soft, velvety blacks, subtle gradations of tone, and atmospheric effects. Using the greasy lithographic crayon on stone, he could achieve a range of textures and tonal depths that perfectly translated his painterly chiaroscuro into print. The medium allowed for a directness and fluidity that complemented his interest in capturing fleeting expressions and intimate moments. His subjects in print were often the same as on canvas: tender scenes of motherhood, portraits of family and friends, and evocative figure studies.

His lithographs were highly regarded in their own right and contributed significantly to his reputation. They were exhibited alongside his paintings and collected by connoisseurs. Works like the lithographic portrait of Paul Verlaine or various Maternité scenes demonstrate his mastery of the medium. For Carrière, lithography was not a secondary activity but an integral part of his artistic output, offering another avenue to explore the interplay of light, shadow, and emotion that defined his unique vision. His skill as a printmaker further underscores his deep understanding of tonal relationships, a cornerstone of his art across different media.

A Network of Influence: Carrière and His Contemporaries

Eugène Carrière moved within a vibrant circle of artists, writers, and intellectuals in late 19th-century Paris. His relationships were often marked by mutual respect and, in some cases, significant artistic exchange. Perhaps his most important connection was with the sculptor Auguste Rodin. The two men shared a deep friendship and a certain aesthetic affinity. Both were interested in conveying powerful emotion and psychological depth, and both experimented with form and finish. Rodin admired Carrière's atmospheric paintings, and some critics suggest Rodin's use of sfumato and the non finito (unfinished) technique in his marble sculptures may have been influenced by Carrière's suggestive, dissolving forms. Conversely, Rodin's expressive power likely resonated with Carrière.

Carrière was also acquainted with other major figures of the era. He painted portraits of the writers Alphonse Daudet, Paul Verlaine, and the Goncourt brothers, as well as the future Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau, indicating his integration into the cultural and political life of the Third Republic. He was associated with the Symbolist movement and thus connected to its key proponents, even if his style remained highly individual. He knew Paul Gauguin, another artist pushing the boundaries of representation, though their artistic paths diverged significantly in terms of colour and subject matter.

His artistic lineage included influences from masters of light and shadow like Rembrandt and the emotional intensity of Romantic painters such as Eugène Delacroix. The atmospheric effects in the works of J.M.W. Turner might also be seen as a precursor to his misty environments. While studying under the academic painter Alexandre Cabanel provided technical grounding, Carrière ultimately charted his own course, distinct from both academicism and the burgeoning Impressionist movement led by figures like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas. His unique position allowed him to connect with various circles, from established figures like Rodin to younger artists who would soon revolutionize art.

Nurturing the Next Generation: The Académie Carrière

Beyond his own artistic production, Eugène Carrière played a significant role as an educator, influencing a generation of artists who would come to define early 20th-century modernism. Around 1890, he opened his own teaching studio, the Académie Carrière, in Paris. This studio quickly attracted students who were seeking alternatives to the rigid instruction of the official École des Beaux-Arts, drawn perhaps by Carrière's reputation for a more personal and expressive approach to art.

The Académie Carrière became an important incubator for emerging talent. Among its most notable students were artists who would soon form the core of the Fauvist movement, known for its radical use of intense, non-naturalistic colour. Henri Matisse, André Derain, Jean Puy, and Albert Marquet all spent time studying under Carrière. Although Carrière's own palette was famously subdued, his emphasis on personal expression, emotional content, and perhaps his structural simplification of form may have resonated with these young artists, even as they moved in a dramatically different direction regarding colour.

Matisse, in particular, acknowledged Carrière's importance, appreciating his encouragement to find one's own artistic voice. While the Fauves' vibrant canvases seem the antithesis of Carrière's misty monochromes, his role as a supportive and open-minded teacher provided a crucial stepping stone for them. The Académie Carrière, therefore, holds a unique place in art history – a studio led by a master of shadow that paradoxically helped nurture the pioneers of explosive colour. This highlights Carrière's significance not just as a painter, but as a facilitator of the artistic innovations that followed him.

Enduring Shadows: Carrière's Influence and Legacy

Eugène Carrière's influence extended beyond the students who passed directly through his Académie. His unique style and thematic concerns left a mark on the broader development of modern art, particularly during the early years of the 20th century. His work served as a bridge between the 19th-century traditions and the radical experiments that were to come. While rooted in Symbolism's focus on inner reality, his formal innovations pointed towards future developments.

The most frequently cited connection is to the early work of Pablo Picasso. During his Blue Period (1901-1904), Picasso employed a similarly restricted, monochromatic palette (though blue rather than brown) and depicted themes of poverty, melancholy, and maternal tenderness that echo Carrière's concerns. While a direct causal link is debated, the prevalence of Carrière's work and reputation in Paris at the turn of the century makes it highly likely that the young Picasso was aware of, and potentially absorbed aspects of, Carrière's atmospheric and emotionally charged style. The emphasis on simplified forms emerging from shadow in both artists' work during these respective periods is notable.

Henri Matisse, despite leading the Fauvist explosion of colour, retained a lifelong respect for Carrière. Beyond the direct tutelage, Carrière's emphasis on expressive form and emotional sincerity may have left a deeper imprint. Furthermore, Carrière's dedication to drawing and his exploration of tonal values provided a solid foundation that even colourists like Matisse could appreciate. Carrière's legacy, therefore, is complex. He was a key figure within Symbolism, a master of intimate psychological portrayal, and an artist whose distinctive visual language, centered on monochrome and mist, resonated with younger artists searching for new ways to express the modern condition, even if their paths ultimately led them towards brighter horizons.

Later Years and Posthumous Recognition

In the later part of his career, Eugène Carrière gained increasing recognition for his unique contribution to French art. He exhibited regularly at progressive venues like the Salon de la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (of which he was a co-founder) and the Salon d'Automne. His work was also shown internationally, including notable appearances at the Venice Biennale, indicating a growing appreciation beyond France. Critics and fellow artists began to more fully acknowledge the power and originality of his vision. His circle of influential friends, including Rodin and Clemenceau, also helped solidify his standing in the cultural landscape.

Despite this growing acclaim, Carrière's final years were marked by illness. He was diagnosed with throat cancer, a condition that gradually worsened and ultimately led to his death in Paris on March 27, 1906, at the age of 57. His passing was mourned by many in the artistic and literary communities who recognized the loss of a unique and sensitive voice. Auguste Rodin, his close friend, was deeply affected by his death.

After his passing, Carrière's reputation continued to be upheld, although his quiet, introspective style was somewhat overshadowed by the more radical movements of Cubism and abstraction that dominated the subsequent decades. However, major retrospectives and continued scholarly interest have ensured his place in art history. Museums like the Musée d'Orsay in Paris and the Strasbourg Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art hold significant collections of his work. His paintings and lithographs are appreciated for their technical mastery, their profound emotional depth, and their distinctive atmospheric quality, securing his legacy as a significant Symbolist painter and an important precursor to certain aspects of modern art.

Carrière's Place in Art History

Eugène Carrière occupies a unique and significant place in the narrative of French art history. As a prominent Symbolist, he contributed to the late 19th-century shift away from Naturalism and Impressionism towards a greater emphasis on subjective experience, emotion, and the inner world. His chosen means of expression – the near-monochromatic palette and misty, dissolving forms – was highly personal and set him apart even within the diverse Symbolist movement, which also included artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, each with their own distinct styles.

His unwavering focus on themes of maternity and family intimacy provided a deeply human counterpoint to some of the more esoteric or decadent strands of Symbolism. He imbued these everyday subjects with a sense of mystery and profound psychological weight, demonstrating that the universal dramas of human connection could be as compelling as any mythological or historical narrative. His technical skill, particularly his mastery of chiaroscuro and tonal harmony, was exceptional, allowing him to create images of remarkable subtlety and emotional power.

Furthermore, Carrière serves as an important transitional figure. His work influenced key pioneers of 20th-century art, notably Picasso during his Blue Period and the Fauves like Matisse and Derain who studied with him. While their subsequent explorations took dramatically different forms, Carrière's emphasis on expressive potential and his departure from strict realism helped pave the way for their bolder experiments. He remains admired for his artistic integrity, his distinctive style, and his sensitive portrayal of the human spirit, securing his legacy as a master of shadow and soul in the annals of art.