Giovanni Costetti, born in Reggio Emilia in 1874 (though some earlier accounts occasionally cite 1878) and passing away in Settignano, near Florence, in 1949, remains a figure of intriguing complexity within the panorama of early twentieth-century Italian art. An artist who defied easy categorization, Costetti navigated the fervent artistic currents of his time, forging a deeply personal visual language. His work, spanning painting, drawing, and printmaking, often delved into the realms of the mystical and the spiritual, marked by an expressive intensity that set him apart from many of his contemporaries. His legacy is that of an artist committed to an introspective journey, seeking what some critics termed the "pure artistic essence."

Early Life and Formative Influences

Costetti's artistic journey began in an Italy rich with cultural heritage and alive with new intellectual ferments. While detailed accounts of his earliest training are somewhat sparse, it is evident that he absorbed the profound lessons of the Florentine Renaissance tradition. This grounding in classical forms and humanistic inquiry provided a bedrock for his later explorations. However, Costetti was not one to remain confined by tradition alone. He was acutely aware of the broader European artistic landscape, particularly the currents of international Symbolism that swept across the continent at the turn of the century.

The Symbolist movement, with its emphasis on suggestion, emotion, and the inner world over direct representation, resonated deeply with Costetti's temperament. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and the later works of the Pre-Raphaelites had paved the way for an art that sought to express ideas and emotions beyond the visible. In Italy, figures like Giovanni Segantini and Gaetano Previati were also exploring Symbolist themes, creating a fertile ground for artists like Costetti.

Literature, too, played a crucial role in shaping his artistic vision. The towering figure of Gabriele d'Annunzio, whose decadent and heroic prose captivated Italy, was a significant presence. Costetti's later work would directly engage with D'Annunzio's themes. Furthermore, his association with literary figures like Gian Papini, a prominent writer and cultural critic, indicates his immersion in the intellectual circles of Florence, a city then buzzing with avant-garde ideas and publications like "La Voce," with which Costetti also had connections.

An intriguing, though less documented, aspect of Costetti's early life, as suggested by some accounts, points to a remarkable musical talent. It is said that he could play the piano by the age of seven and even made early stage appearances. While his family might have envisioned a different path for him, potentially in the family's traditional business, Costetti's artistic inclinations, whether initially musical or visual, ultimately guided his career. This multifaceted early talent hints at a sensitivity and creative drive that would later manifest powerfully in his visual art.

A Singular Artistic Vision: Style and Philosophy

Giovanni Costetti's artistic style is notoriously difficult to pigeonhole into any single "-ism" of the early 20th century. This elusiveness is, in itself, a testament to his independent spirit. During the first two decades of the century, his work often displayed pronounced expressionistic characteristics. This was not necessarily an adherence to German Expressionism as a formal movement, but rather an innate tendency towards conveying intense emotional states and spiritual inquiries through potent, sometimes unsettling, imagery.

His exploration of the mystical and the spiritual was a consistent thread. Costetti sought to transcend mere surface appearances, aiming to capture an underlying reality or a heightened psychological state. This pursuit often led him to blend elements of realism with what might be described as a proto-surrealist sensibility. His figures, while often grounded in recognizable forms, could inhabit dreamlike spaces or be imbued with an enigmatic aura.

Critics of the time noted his quest for a "pure artistic essence." This suggests a desire to strip away superfluous detail and academic convention to arrive at a more direct and potent form of expression. His line could be incisive and searching, his compositions often unconventional, prioritizing emotional impact over strict adherence to traditional aesthetics. He was a painter of interiors, both physical and psychological, often focusing on portraiture that aimed to reveal the sitter's inner life rather than just their external likeness.

The influence of the Florentine Renaissance, particularly its emphasis on drawing (disegno) as the foundation of art, remained palpable. Yet, Costetti filtered this tradition through a modern sensibility, one that was open to the anxieties, aspirations, and spiritual searching of his own era. His color palette could range from somber and introspective to moments of surprising vibrancy, always in service of the work's expressive goals.

Masterpieces and Key Works

Giovanni Costetti's oeuvre includes a number of significant paintings and graphic works that exemplify his unique artistic concerns. Among his most noted pieces is the etching La Fossa Fu fune dalla Nave di Gabriele d'Annunzio (The Grave Was the Mooring Rope of Gabriele d'Annunzio's Ship), created in 1908. This powerful work, inspired by a contemporary tragic event and clearly referencing the literary titan D'Annunzio, was first exhibited at the Società delle Belle Arti (often referred to as the Medici Gallery in some contexts) in Florence. Its dramatic intensity and evocative title highlight Costetti's ability to translate literary and emotional themes into compelling visual statements. The etching subsequently traveled to exhibitions in other Italian cities, including Pistoia, Rimini, and Turin, attesting to its contemporary impact.

Another key work is Gianfallo, a striking portrait of the writer Gian Papini, painted in 1902. Papini was a leading and often controversial intellectual figure in Florence, and Costetti's portrayal likely aimed to capture the intensity and complexity of his personality. This work underscores Costetti's engagement with the cultural figures of his time and his skill in portraiture as a means of psychological exploration.

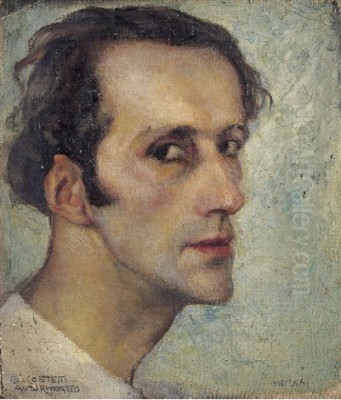

His portraits, in general, form a significant part of his output. Augusto Hermet in White (Ritratto di Augusto Hermet), an oil painting, and the Portrait of Carla Guarnieri are further examples of his capacity to convey character and mood. These works often feature a focused intensity, where the sitter's gaze or posture suggests a rich inner world. The painting Donna con cappello (Woman with a Hat) also showcases his ability to imbue a seemingly conventional subject with a distinct atmosphere and psychological depth.

These works, whether oil paintings or etchings, demonstrate Costetti's technical versatility and his consistent thematic preoccupations. He moved between the intimacy of portraiture and the broader allegorical or narrative potential of printmaking, always with a distinctive voice that sought to explore the human condition in its more profound and often unsettling aspects.

Prowess in Printmaking and Graphic Arts

While a gifted painter, Giovanni Costetti also distinguished himself significantly in the realm of printmaking, particularly etching. His mastery of this medium allowed for a different kind of expressive power, one that relied on the incisive line, the dramatic interplay of light and shadow, and the potential for wider dissemination. Works like La Fossa Fu fune dalla Nave di Gabriele d'Annunzio are prime examples of his skill in translating complex emotional and narrative ideas into the demanding medium of etching.

His involvement with the influential literary and arts magazine L'Eroica, edited by Ettore Cozzani, further highlights his standing in the graphic arts. A drawing by Costetti, dedicated to Cozzani, was published in the magazine, placing him within a circle of artists and writers who valued high-quality graphic work and illustration. L'Eroica was known for its promotion of woodcuts and other printmaking techniques, championing a revival of these arts.

Costetti's graphic works were not limited to standalone prints. He also contributed illustrations, for instance, to musical works, such as an edition related to Beethoven's La voce del demonio (The Voice of the Demon). This engagement with music and literature through illustration demonstrates the breadth of his artistic interests and his ability to adapt his style to different contexts while maintaining his characteristic intensity. The "Prima Mostra di Bianco e Nero" (First Exhibition of Black and White) in 1913, where his works were shown, further underscores the recognition he received for his contributions to the graphic arts.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Critical Reception

Throughout his career, Giovanni Costetti's work was featured in a number of important exhibitions, bringing his unique vision to a wider public and garnering critical attention. The aforementioned 1908 exhibition of La Fossa Fu fune dalla Nave di Gabriele d'Annunzio at the Società delle Belle Arti in Florence was an early mark of recognition, followed by its showings in other Italian cities.

A significant event was the "Prima Mostra di Bianco e Nero" held in 1913, which specifically showcased works in black and white, including paintings and prints. Costetti's participation alongside artists like one referred to as Romeo (possibly Romeo Costetti, though this requires further clarification if they are distinct individuals) highlighted his strength in graphic media and monochromatic compositions.

Perhaps one of the most notable exhibitions he was involved in was the "Fiorentina Primaverile" (Florentine Spring Exhibition) of 1922. This major showcase of contemporary Italian art brought together a diverse range of artists. Costetti was described in relation to this exhibition as a "spiritualist" artist, a label that, while perhaps simplistic, points to the perceived mystical and introspective qualities of his work. He reportedly held the exhibited works in high regard. This exhibition also featured prominent artists of the era, including figures associated with Futurism and other modern movements, such as Gino Severini and the Florentine painter Ottone Rosai. Costetti's presence in such a diverse and significant show indicates his relevance within the broader Italian art scene of the post-World War I period.

His works were also exhibited at venues such as the Isolato San Rocco in his native Reggio Emilia and the Permanente Museum in Milan. Furthermore, Costetti's paintings and drawings have appeared in auctions over the years, such as the oil painting of Augusto Hermet, indicating a continued, if specialized, market interest in his art. The critical attention he received often focused on the unique, hard-to-classify nature of his style and his pursuit of a deeply personal, spiritually infused art.

A Network of Contemporaries: Friendships and Artistic Dialogues

Giovanni Costetti was not an isolated figure; he moved within a vibrant network of artists, writers, and intellectuals, engaging in dialogues that undoubtedly shaped his own artistic path and, in turn, influenced others.

A particularly significant relationship was with the Italian woman painter Fillide Giorgi Lazzanti. Sources suggest a deep emotional bond between them, and Costetti's influence on her artistic development was considerable. Under his sway, Lazzanti reportedly turned her attention towards German art, undertaking frequent travels between 1906 and 1910 to cities like Munich, Geneva, and Leipzig. During this period, she absorbed the lessons of Post-Impressionism and the color research of Secessionist movements, reflecting a cross-pollination of ideas likely fostered by her connection with Costetti. Her association, like Costetti's, with the circle around the magazine La Voce further cemented their place within Florence's avant-garde.

Costetti also played the role of mentor. The Argentine artist Domingo Candia was one of his students in Florence. Their friendship, initiated in Candia's Florentine studio, later continued and developed in Buenos Aires, suggesting a lasting impact and a transatlantic connection.

His appreciation for the work of fellow artists is evident in his admiration for the Spanish etcher Joaquim Sunyer. Sunyer's prints were highly esteemed at the time, and Costetti was among those who recognized and supported his talent, indicating Costetti's discerning eye for quality in graphic arts beyond his own production.

There are also documented connections with Giovanni Costa (often known as Nino Costa), a pivotal figure in the Macchiaioli movement and later a significant influence on Symbolist landscape painting in Italy. While the exact nature of their interaction requires deeper research, their shared Italian artistic heritage and overlapping periods suggest potential for mutual awareness, if not direct collaboration. Costa's own international connections, particularly with British artists like Frederic Leighton and George Howard, Earl of Carlisle, highlight the cosmopolitan art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Costetti's collaborative spirit is also suggested by mentions of joint projects with artists like A. De Carolis (Adolfo De Carolis), another prominent figure in Italian Symbolism and a master of woodcut and illustration. Such collaborations were common in an era where artists often worked together on decorative schemes, publications, or manifestos.

The intellectual milieu of Florence, with figures like Gian Papini and the writers and artists associated with La Voce, such as Ardengo Soffici and Giuseppe Prezzolini, provided a stimulating environment. While Costetti may not have formally aligned himself with any specific group or manifesto promoted by these figures, his presence in Florence during this dynamic period ensured his engagement with the prevailing artistic and literary debates.

The "Fiorentina Primaverile" of 1922: A Moment of Synthesis

The "Mostra Fiorentina Primaverile" of 1922 stands as a significant landmark in early 20th-century Italian art and provides a valuable context for understanding Costetti's position. Held in Florence, this large-scale exhibition aimed to showcase the diverse currents of contemporary Italian art in the aftermath of World War I. It was a period of reassessment, with artists exploring various paths, from a "return to order" and classical values to continued avant-garde experimentation.

Costetti's participation and the description of him as a "spiritualist" artist are noteworthy. This label suggests that his work was perceived as distinct from the more formal or politically charged concerns of movements like Futurism (whose leading figures included Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, and Carlo Carrà) or the emerging Novecento Italiano, which would soon advocate for a renewed classicism under the guidance of figures like Margherita Sarfatti.

The "Fiorentina Primaverile" featured a wide array of artists, including those who had been part of the Futurist vanguard, like Gino Severini, and others who were developing more personal, often introspective styles, like Ottone Rosai. The inclusion of Costetti among such a diverse group underscores his recognized, albeit unique, contribution to the Italian art scene. His work, with its focus on inner states and mystical themes, offered a different kind of modernism, one less concerned with the machine age or overt stylistic revolution, and more with the enduring questions of the human spirit. The exhibition itself was a testament to the plurality of artistic expression in Italy at the time, a complex tapestry to which Costetti added his distinctive thread.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Information about Giovanni Costetti's later career, particularly from the 1930s until his death in 1949, is less extensively documented in readily available summaries compared to his earlier, more dynamic period. However, his foundational work in the first few decades of the 20th century established his reputation as an artist of profound individuality. He continued to live and work, primarily in the region of Florence, passing away in Settignano, a village in the Florentine hills that has long attracted artists and writers.

Costetti's legacy lies in his unwavering commitment to a deeply personal and spiritually infused art. He was not a trend-follower; rather, he carved out a niche for himself, exploring themes of introspection, mystery, and the human psyche with a distinctive visual language. His portraits go beyond mere likeness, seeking to capture the essence of his subjects, while his narrative and allegorical works, especially his etchings, possess a potent, often haunting, quality.

While he may not have achieved the widespread international fame of some of his Italian contemporaries who were associated with more prominent movements, Costetti's work continues to be valued by connoisseurs and scholars of Italian modernism. His art offers a crucial counterpoint to the more outwardly radical or politically engaged art of his time, reminding us of the persistent human need for introspection and the exploration of the spiritual, even amidst an era of rapid societal and artistic change. His influence on artists like Fillide Giorgi Lazzanti and his role as a teacher to figures like Domingo Candia also form part of his contribution.

The renewed interest in Symbolist and Expressionist currents, and in artists who operated somewhat outside the dominant narratives of art history, may well lead to a deeper appreciation of Giovanni Costetti's unique and compelling body of work. He remains a testament to the power of individual vision in an age of collective movements.

Conclusion: An Artist of Inner Landscapes

Giovanni Costetti stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the rich tapestry of early 20th-century Italian art. Born in 1874, his career unfolded during a period of intense artistic innovation and cultural upheaval. Resisting easy classification, he wove together influences from the Florentine Renaissance, international Symbolism, and a deeply personal spiritual quest, often inflected with an expressionistic intensity.

His portraits, such as those of Gian Papini and Augusto Hermet, delve into the psychological depths of his sitters, while his masterful etchings, like La Fossa Fu fune dalla Nave di Gabriele d'Annunzio, demonstrate his ability to convey complex emotional and narrative themes with graphic power. His connections with literary figures like D'Annunzio and Papini, and his interactions with fellow artists including Fillide Giorgi Lazzanti, Giovanni Costa, and A. De Carolis, place him firmly within the vibrant cultural milieu of his time.

Participation in significant exhibitions like the "Fiorentina Primaverile" of 1922, where he was noted for his "spiritualist" tendencies alongside artists such as Gino Severini and Ottone Rosai, highlights his recognized, if distinct, voice. Costetti's pursuit of a "pure artistic essence" led him to create an oeuvre that prioritized introspection and emotional resonance over adherence to any single stylistic dogma. He remains a compelling example of an artist dedicated to exploring the inner landscapes of the human experience, leaving behind a body of work that continues to intrigue and reward those who seek art that speaks to the soul.