Paul Iribe stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from the floral exuberance of Art Nouveau to the streamlined sophistication of Art Deco. A multifaceted talent, he was an illustrator, designer, publisher, and artistic visionary whose influence permeated fashion, decorative arts, and even cinema in the early twentieth century. His distinctive style, characterized by bold lines, vibrant yet refined color palettes, and a keen sense of modern elegance, not only captured the zeitgeist of his era but also helped to define it. From his groundbreaking fashion illustrations for Paul Poiret to his luxurious jewelry designs for Coco Chanel and his forays into Hollywood, Iribe left an indelible mark on the visual culture of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born Joseph Paul Iribe on June 8, 1883, in Angoulême, France, to a family of Basque origin, his father being Jules Jean Iribe. This heritage, though not overtly dominant in his later work, perhaps contributed to a certain boldness and clarity in his artistic vision. His formative years were spent in Paris, the undisputed cultural capital of the world at the turn of the century. He received his formal artistic training at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, a crucible for many great talents, and later attended the Collège Rollin. It was during these student years that he forged friendships with individuals who would also become significant figures in the world of illustration and design, notably George Barbier and Pierre Brissaud. These early connections and shared artistic explorations undoubtedly played a role in shaping his burgeoning aesthetic sensibilities.

Iribe's professional career began modestly, working as a typographer and apprentice printer. This hands-on experience with the mechanics of print and layout would prove invaluable, giving him a deep understanding of graphic design principles. He soon transitioned to illustration, contributing drawings and caricatures to popular Parisian newspapers and satirical journals such as L'Assiette au Beurre, Le Rire, and Sourire. His sharp wit and keen observational skills found an early outlet in these publications. In 1906, demonstrating his entrepreneurial spirit and desire for an independent platform, Iribe founded his own satirical magazine, Le Témoin (The Witness). This journal, which he revived several times throughout his career, became known for its incisive social and political commentary, often delivered through Iribe's striking and minimalist graphics, which already hinted at the elegance and stylization that would become his hallmark. His work for Le Témoin often showcased a strong influence from Japanese ukiyo-e prints, particularly in its use of flat color planes, bold outlines, and asymmetrical compositions, a stylistic trait shared by contemporaries like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Revolutionizing Fashion Illustration: The Poiret Collaboration

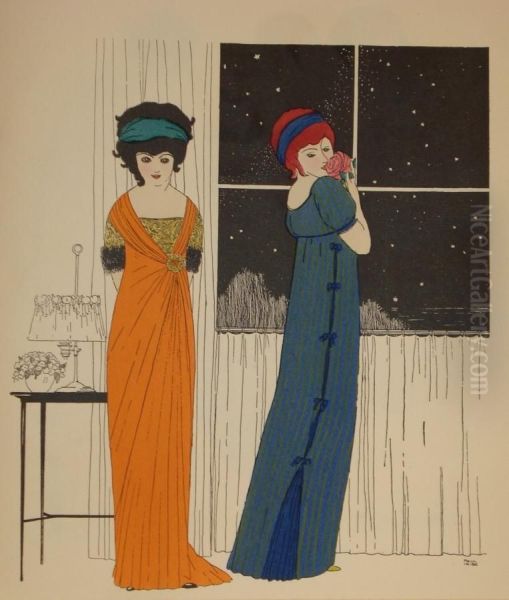

The year 1908 marked a watershed moment in Iribe's career and in the history of fashion illustration. The avant-garde couturier Paul Poiret, a revolutionary figure who was liberating women from corsets and introducing fluid, Oriental-inspired silhouettes, commissioned Iribe to create a promotional portfolio for his designs. The resulting publication, Les Robes de Paul Poiret racontées par Paul Iribe, was a triumph. It was not merely a catalogue of dresses but an art object in itself, a luxurious limited-edition album that redefined how fashion could be presented.

Iribe utilized the pochoir technique, a refined stencil-based hand-coloring method, to produce images of extraordinary vibrancy and clarity. This technique, favored by many luxury illustrators of the period like André Marty and Charles Martin, allowed for rich, opaque colors and sharp definition, perfectly suited to Iribe's bold graphic style. His illustrations depicted slender, elegant women, often in theatrical or narrative settings, showcasing Poiret's gowns not as static garments but as integral components of a modern, sophisticated lifestyle. The figures were stylized, their forms simplified, and the emphasis was on the silhouette and the decorative qualities of the design. This approach was a radical departure from the more detailed and conventional fashion plates of the preceding era. It marked the true beginning of modern fashion illustration, treating it as an art form capable of interpreting and enhancing the designer's vision. The success of this collaboration cemented Iribe's reputation and set a new standard for fashion presentation. He would later collaborate again with Poiret, alongside Georges Lepape, on Les Choses de Paul Poiret vues par Georges Lepape (1911), further solidifying this new artistic direction in fashion.

The Flourishing of a Distinctive Style: La Gazette du Bon Ton and Beyond

Following the success with Poiret, Iribe became a sought-after illustrator and designer. He was a key contributor to La Gazette du Bon Ton, the influential Parisian fashion journal founded by Lucien Vogel in 1912. This lavish publication featured the work of the era's leading illustrators, including the aforementioned George Barbier, Pierre Brissaud, Georges Lepape, André Marty, and Charles Martin, as well as Bernard Boutet de Monvel. Iribe's contributions to the Gazette further showcased his elegant line, his sophisticated use of color, and his ability to capture the essence of contemporary chic. His women were the epitome of modern grace, exuding an air of confidence and understated glamour.

Beyond fashion illustration, Iribe's talents extended to a wide array of design fields. He designed textiles, wallpapers, furniture, and stage sets. His "Iribe rose," a stylized floral motif, became a popular decorative element in the 1910s and 1920s, appearing on fabrics and in interior schemes. He opened his own decorative arts shop, showcasing his unique vision for modern living. His furniture designs often featured luxurious materials, clean lines, and a subtle opulence that prefigured the full flowering of Art Deco. He understood that style was an immersive experience, encompassing not just clothing but the entire environment. His work in theatre design, though less documented, allowed him to explore narrative and atmosphere on a larger scale, skills that would later serve him well in Hollywood. He also continued his satirical work, with Le Témoin making sporadic reappearances, allowing him to comment on the rapidly changing social and political landscape, including the upheavals of World War I.

Hollywood Interlude: Designing for the Silver Screen

The allure of Hollywood, with its burgeoning film industry and demand for artistic talent, drew Iribe to the United States in 1919. He initially worked in New York before making his way to California. His reputation as a sophisticated Parisian designer preceded him, and he soon found employment with some of the era's most prominent film directors. He was notably engaged by the legendary Cecil B. DeMille, a director known for his lavish spectacles and historical epics. Iribe served as an artistic director and designed costumes and elaborate sets for several of DeMille's films, including the 1923 silent version of The Ten Commandments. His contributions brought a distinct European elegance and a modern sensibility to Hollywood productions.

During his Hollywood period, Iribe also worked on other films, applying his design expertise to create visually stunning environments and costumes that enhanced the narrative and glamour of the silver screen. This experience broadened his artistic horizons and exposed his work to an even wider international audience. While in Hollywood, he moved in circles that included other European émigrés and American creatives, further expanding his network and influences. His time in America, though impactful, was an interlude, and by the late 1920s, he was drawn back to Paris.

Parisian Renaissance and the Chanel Alliance

Upon his return to Paris, Iribe re-established himself as a leading figure in the city's vibrant artistic and design scene. The Art Deco movement was now in full swing, and Iribe, as one of its progenitors, was perfectly positioned to contribute to its continued evolution. It was during this period that he formed a significant personal and professional relationship with another icon of modern style: Coco Chanel.

Chanel, who had revolutionized womenswear with her emphasis on comfort, simplicity, and understated elegance, found a kindred spirit in Iribe. Their shared aesthetic vision, which valued clean lines, luxurious materials, and a rejection of excessive ornamentation, led to a fruitful collaboration. Iribe became Chanel's lover and a key artistic advisor. One of their most notable joint ventures was the creation of a spectacular collection of diamond jewelry in 1932, commissioned by the International Guild of Diamond Merchants. Titled "Bijoux de Diamants," the collection was exhibited at Chanel's townhouse and caused a sensation. Iribe's designs for these pieces were innovative, often featuring celestial motifs like comets and stars, and were designed to be versatile and modern, reflecting Chanel's own approach to fashion. The pieces were a departure from traditional fine jewelry, emphasizing fluidity and a lighter, more graphic sensibility, much like the work of contemporary jewelers such as René Lalique (though Lalique's earlier work was more Art Nouveau) or Suzanne Belperron.

Beyond jewelry, Iribe also lent his talents to Chanel's broader brand identity. He designed advertisements and contributed to her image. He also continued his independent work, notably creating striking promotional albums for the wine merchant Nicolas. These albums, such as Rose et Noir (1930) and Blanc et Rouge (1931), were masterpieces of graphic design and subtle advertising, using witty illustrations and sophisticated layouts to promote the brand. They often featured his characteristic elegant figures and a refined sense of humor, showcasing his enduring skill as a graphic artist. He also briefly revived Le Témoin again in 1933, this time with a strong nationalist and somewhat controversial political stance, reflecting the turbulent atmosphere of the pre-war years.

Artistic Style: The Essence of Iribe

Paul Iribe's artistic style is instantly recognizable for its refined elegance, its graphic clarity, and its modern sensibility. He masterfully blended simplicity with luxury, creating images and objects that were both sophisticated and accessible. Several key characteristics define his work:

Bold Line Work: Iribe possessed an exceptional command of line. His outlines are clean, precise, and expressive, defining forms with an economy of means. This is evident in his fashion illustrations, caricatures, and decorative designs.

Stylized Figures: His human figures, particularly women, are typically slender, elongated, and graceful. They embody an idealized modern elegance, often depicted in dynamic or poised poses that convey a sense of movement and sophistication.

Pochoir and Color: His early adoption and mastery of the pochoir technique allowed him to achieve vibrant, flat areas of color that contributed to the graphic impact of his work. His color palettes were often bold yet harmonious, using contrasting hues to create visual excitement or subtle gradations for a more understated effect. He frequently employed black as a dramatic counterpoint.

Influence of Japanese Prints: Like many artists of his generation, including Edgar Degas and Mary Cassatt in earlier decades, Iribe was influenced by Japanese ukiyo-e prints. This can be seen in his use of asymmetrical compositions, flattened perspectives, and decorative patterning.

Art Deco Sensibility: While a precursor, his work fully embraced the core tenets of Art Deco: a love for geometric forms, symmetry (though often played against asymmetry), luxurious materials, and a celebration of modernity and the machine age, albeit often softened with classical or exotic motifs. His work shares common ground with other Art Deco masters like furniture designer Jacques-Émile Ruhlmann or lacquer artist Jean Dunand.

Narrative and Wit: Many of Iribe's illustrations, even in fashion, possess a narrative quality or a touch of subtle humor. His satirical drawings, of course, were overtly witty and critical. This ability to imbue his work with personality and intelligence set him apart.

Versatility: Iribe was not confined to one medium. His ability to apply his distinctive style across illustration, furniture design, jewelry, textiles, and graphic arts demonstrates his remarkable versatility and holistic vision of design. He shared this multidisciplinary approach with other Art Deco figures like Erté (Romain de Tirtoff), who also excelled in fashion, costume, and set design.

Contemporaries and Lasting Influence

Paul Iribe did not operate in a vacuum. He was part of a vibrant artistic community in Paris and later in Hollywood. His collaborations with Paul Poiret and Coco Chanel were defining partnerships. His friendships with George Barbier and Pierre Brissaud, and his work alongside illustrators like Georges Lepape, André Marty, and Charles Martin for publications like La Gazette du Bon Ton, placed him at the center of the era's graphic arts revolution. His social circle included influential figures like the patron Misia Sert and the multifaceted artist Jean Cocteau, who, like Iribe, moved fluidly between different artistic disciplines.

His influence on fashion illustration was profound, shifting the focus from mere representation to artistic interpretation. He helped to establish illustration as a powerful tool for branding and storytelling in the fashion industry. His work in decorative arts contributed to the development of the Art Deco style, promoting an aesthetic that was both modern and luxurious. Even his brief foray into film design left a mark, bringing a sophisticated European sensibility to Hollywood productions. Designers like Lucien Lelong, for whom Iribe also worked, recognized his unique ability to convey modern chic.

Final Years and Enduring Legacy

In the early 1930s, Iribe was at the height of his powers, a respected designer and a close associate of Coco Chanel. There were even rumors that they planned to marry. However, his life was cut tragically short. On September 21, 1935, while playing tennis at Chanel's villa, Roquebrune, on the French Riviera, Paul Iribe collapsed and died of a heart attack. He was only 52 years old.

His sudden death was a shock to the art and fashion worlds. Coco Chanel was reportedly devastated. Despite his relatively short life, Paul Iribe left behind a rich and varied body of work that continues to be celebrated for its elegance, innovation, and enduring style. His contributions were crucial in shaping the visual language of Art Deco and in elevating fashion illustration to a true art form. His designs, whether for a Poiret gown, a Chanel necklace, or a satirical journal, all bear the unmistakable imprint of his sophisticated vision. Today, his works are held in major museum collections and are highly prized by collectors, a testament to his lasting importance as one of the key figures of early twentieth-century design and illustration. He remains an inspiration for designers and illustrators who seek to capture the essence of modern elegance with clarity, wit, and artistic integrity.