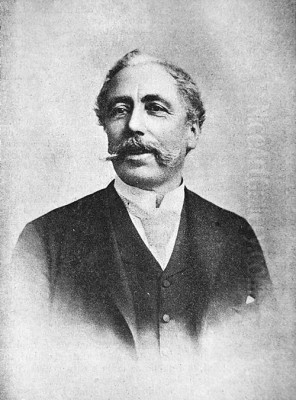

Eugenio Cecconi stands as a significant figure in late 19th-century Italian art, particularly associated with the vibrant artistic milieu of Tuscany. Born in the bustling port city of Livorno in 1842 and passing away in the cultural heart of Florence in 1903, Cecconi's life spanned a period of profound change in Italian art. He navigated these currents with a distinct vision, dedicating his talents primarily to capturing the landscapes, rustic scenes, and animal life of his native region, often infused with a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that connected him to the influential Macchiaioli movement. Beyond his canvases, Cecconi was a man of diverse interests, engaging with the worlds of literature and art criticism, leaving behind a legacy that reflects both artistic dedication and intellectual breadth.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Eugenio Cecconi's artistic journey formally began in Florence, the cradle of the Renaissance and a continuing center for artistic innovation in the 19th century. In 1862, he enrolled at the prestigious Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts). This institution was a cornerstone of artistic training in Tuscany, though it was also a place where traditional academic methods were increasingly being questioned by a younger generation of artists seeking new modes of expression.

At the Academy, Cecconi studied under Enrico Pollastrini (1817-1876), a respected painter known for his historical and literary subjects, executed in a style that adhered more closely to academic conventions. Pollastrini's tutelage would have provided Cecconi with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and traditional painting techniques. However, the artistic air Cecconi breathed in Florence was filled with more radical ideas, particularly those emanating from the Caffè Michelangiolo, the legendary meeting place for the Macchiaioli painters.

Enrico Pollastrini himself was an influential teacher, shaping several notable artists of the period. Among Cecconi's contemporaries who also studied under Pollastrini were figures who would achieve considerable fame, such as Giovanni Fattori, arguably the most celebrated of the Macchiaioli; Silvio Lega, another key member of the Macchiaioli known for his intimate domestic scenes; Stefano Ussi, who gained renown for his large-scale historical paintings; Federico Andreotti, who also studied with Angiolo Tricca and became known for his elegant Rococo-revival genre scenes; and Eliseo Sala, who developed a successful career as a portraitist and historical painter. This connection placed Cecconi within a network of emerging talents, even if his own path would diverge slightly from strict academicism.

The Macchiaioli Connection: A Shared Sensibility

While Cecconi is often associated with the Macchiaioli, his relationship with the movement is nuanced. He is generally considered a later adherent, joining or aligning himself with their principles after the group's most formative years in the 1850s and early 1860s. The Macchiaioli, whose name derives from the Italian word "macchia" (meaning patch, spot, or stain), rebelled against the polished finish and historical or mythological subject matter favored by the academies. They advocated for painting outdoors (plein air) and capturing the immediate effects of light and shadow using distinct patches of color, often applied directly to the canvas with little preliminary drawing.

Their subjects were drawn from everyday life, contemporary events (like the Risorgimento), and the landscapes of Tuscany. Key figures like Giovanni Fattori, Telemaco Signorini, Silvio Lega, Giuseppe Abbati, and Odoardo Borrani frequented the Caffè Michelangiolo, debating art and developing their revolutionary approach. Cecconi, while perhaps not part of the initial, most radical phase, clearly absorbed their influence and shared their commitment to realism and the depiction of Tuscan life and light.

His association is evident in his choice of subjects – rural landscapes, scenes of peasant life, animals, particularly horses and hunting dogs – and his attention to the effects of natural light. He exhibited alongside Macchiaioli artists and shared friendships and professional connections with many of them. For instance, he is known to have exhibited with Giuseppe Abbati, whose work reportedly had a profound impact on him. He also moved in circles that included Francesco Giolli and Francesco Giorgi, artists who, like Cecconi, contributed to the evolution of this new, modern approach to painting rooted in direct observation and a synthesis of form through color and light.

Artistic Style: Realism, Nature, and Tuscan Light

Cecconi developed a style characterized by meticulous observation and a deep understanding of the natural world. While influenced by the Macchiaioli's emphasis on light and color patches, his work often retained a greater level of detail and finish compared to the more synthetic approach of some core members of the group. His paintings demonstrate a commitment to realism, capturing the textures of the land, the anatomy of animals, and the specific character of the Tuscan countryside.

Landscapes formed a significant part of his oeuvre. He was particularly drawn to the Maremma, a coastal area in southern Tuscany known for its wild beauty, pine forests (pinete), and traditional agricultural practices, including cattle herding by the distinctive butteri (cowboys). Works like PINETA Maremma reflect this interest. He also painted scenes closer to his native Livorno, capturing the coastal light and atmosphere, possibly including views like the famous cliffs of Calafuria, a subject favored by many Macchiaioli painters (the mentioned Ciaenole di Livorno likely refers to such coastal scenes).

Animals, especially horses and dogs, were frequent subjects, rendered with anatomical accuracy and empathy. Hunting scenes were a recurring theme, allowing him to combine his skill in depicting animals with landscape settings and human figures engaged in traditional rural activities. These works often convey a sense of camaraderie and the rhythms of country life. His figures, typically peasants, hunters, or rural women, are portrayed with dignity and authenticity, integrated naturally into their environment.

His palette was often attuned to the specific light conditions of Tuscany – the bright sunlight casting strong shadows, the softer light of dawn or dusk (Tramonto in primavera - Sunset in Spring). He masterfully handled light to define form, create atmosphere, and imbue his scenes with a sense of immediacy and lived experience. The combination of detailed rendering and sensitivity to light effects gives his work a unique position, bridging academic training with the modern sensibilities of the Macchiaioli.

Notable Works: Capturing Moments of Life

Several works stand out in Eugenio Cecconi's production, showcasing his characteristic themes and stylistic strengths.

Sosta dei cacciatori per far abbeverare i cavalli (Hunters' Rest to Water the Horses), an oil painting dated 1883, is a prime example of his interest in hunting themes and his skill in depicting horses. The elongated format (26.5 x 68 cm) suggests a panoramic view, likely focusing on a group of hunters paused during their excursion, attending to their animals. Such scenes allowed Cecconi to display his detailed knowledge of equine anatomy and the specific gear associated with hunting, all set within a carefully rendered landscape. This work, noted as being in the collection of Sir Basil Scott's family in London, highlights the appreciation his art found even beyond Italy.

Donna in Lettura (Woman Reading) presents a more intimate subject. Dated broadly between 1885 and 1930 in one source (though the end date must be before his death in 1903, suggesting the work belongs to his mature period, likely the late 1880s or 1890s), this painting (40 x 50.7 cm) likely depicts a quiet domestic moment. Such genre scenes were popular, and Cecconi's interpretation would probably focus on the play of light on the figure and her surroundings, capturing a moment of personal reflection. The high estimate or price mentioned in one auction context (€70,000) indicates the significant value attributed to his major works.

L'ombrello (The Umbrella), sometimes referred to as L'ombello bianco (The White Umbrella), is another notable piece. Umbrellas or parasols often feature in late 19th-century painting, associated with leisure, modernity, and sometimes Impressionist influences in their depiction of light filtering through or reflecting off the fabric. Its appearance in a 2024 auction with an estimate of €3,500-€5,000 shows the continued market interest in his work. This painting likely captures a figure, perhaps female, in an outdoor setting, the umbrella serving as a focal point for exploring light effects.

Other titles mentioned, such as Contadina nel borgo (Peasant Woman in the Village), Assembly of Hunters, and Days of Rest, reinforce his focus on rural life and genre scenes. Profilo di Uomo (Profile of a Man), a drawing, indicates his activity in other media besides oil painting, showcasing his foundational skills in draughtsmanship. Works like PINETA Maremma confirm his dedication to specific Tuscan landscapes. Collectively, these works paint a picture of an artist deeply engaged with the visual realities of his time and place.

Beyond the Canvas: Writer, Critic, and Man of Culture

Eugenio Cecconi's talents were not confined to the visual arts. He was also recognized as a capable writer and art critic, contributing articles on art and potentially authoring literary works. Sources mention titles like Lost Appeal and Livorno's Rest Day, though further verification might be needed regarding their exact nature and publication. This literary activity demonstrates an intellectual engagement with the art world that went beyond mere practice. His critical writings likely offered insights into his own artistic philosophy and his perspective on the contemporary art scene in Florence and Italy.

This multifaceted nature extended to other areas of life. An interesting anecdote reveals his involvement in architectural preservation: Cecconi purchased and restored the ancient Lecceto Monastery (Eremo di Lecceto), located in the hills near Florence, transforming it into his summer residence. This act suggests an appreciation for history and architecture, and a desire to preserve cultural heritage, aligning with a broader 19th-century interest in historical revival and preservation.

Another intriguing aspect of his life involved a connection to the Church. He reportedly served as a historian for a commission of the Holy See (Vatican). In recognition of this service, he was presented with a valuable silver-gilt chalice dedicated to the Holy Trinity. Cecconi later demonstrated his piety and connection to the local church by donating this significant object to Gioacchino Limberti, the Archbishop of Florence at the time. These episodes paint a picture of a man integrated into the cultural, historical, and even religious fabric of his society.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Context

Cecconi's career unfolded within a rich network of artistic relationships. His time studying under Pollastrini placed him alongside future stars like Fattori and Lega. His later association with the Macchiaioli brought him into contact with figures like Abbati and potentially Signorini, the group's main theorist. His shared focus on Tuscan themes connected him with contemporaries like Niccolò Cannicci and Plinio Nomellini, artists who also contributed to the transition towards modern painting in the region, exploring light and landscape with fresh eyes.

A particularly notable connection was with Giovanni Boldini, the internationally renowned portraitist also from Ferrara but active in Florence during the 1860s. Cecconi is said to have shared studio space with Boldini for a time in Castiglione di Garfagnana. This interaction, even if temporary, would have exposed Cecconi to Boldini's dazzling brushwork and sophisticated modernity, offering a different perspective from the earthier realism of the Macchiaioli.

He also likely knew other artists associated with the Macchiaioli circle, such as Antonio Puccini, whose work often depicted coastal scenes and military life. The Florentine art scene, centered around the Academy, private studios, exhibition societies (like the Società Promotrice di Belle Arti), and cafes like the Michelangiolo, fostered constant interaction and exchange of ideas. Cecconi participated in this vibrant environment, exhibiting his works not only in Florence but also in other major Italian cities like Rome and Turin.

His work should be seen in the context of Italian art after the Unification (Risorgimento), a period marked by a search for a modern national artistic identity. Realism, Verismo (in literature and opera), and movements like the Macchiaioli represented attempts to break from academic constraints and engage directly with contemporary life and the Italian landscape. Cecconi's art, with its focus on specific Tuscan realities rendered with careful observation and sensitivity to light, fits squarely within this broader cultural project.

Legacy and Recognition

Eugenio Cecconi occupies a respected place in the history of 19th-century Italian art, particularly within the Tuscan school. While perhaps not as revolutionary as the founding members of the Macchiaioli, he was a highly skilled painter who absorbed their innovations while maintaining his own distinct voice, characterized by a blend of realism, detailed observation, and atmospheric sensitivity. His depictions of the Tuscan countryside, rural labor, hunting scenes, and animal life contribute significantly to the visual record of the region during his time.

His dual talents as a painter and writer/critic mark him as a cultured figure, deeply engaged with the artistic and intellectual currents of his era. The anecdotes concerning the Lecceto Monastery and the Vatican chalice add further dimensions to his biography, revealing interests beyond the studio.

His works continue to be appreciated and sought after, appearing in exhibitions and auctions, as evidenced by the recent sales and listings mentioned. Catalogues from auction houses like Casa d'Aste provide valuable records of his output, detailing works like PINETO Maremma and L'ombello bianco, often tracing their provenance through significant collections like that of Mario Galli. The presence of his paintings in private and potentially public collections ensures his contribution is not forgotten.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Tuscany

Eugenio Cecconi's artistic legacy is firmly rooted in the landscapes and life of Tuscany. As a painter, he combined the rigorous training of the Florentine Academy with the modern sensibilities of the Macchiaioli, forging a style that was both realistic and evocative. His meticulous depictions of nature, animals, and rural scenes offer a window into the world of late 19th-century Italy, captured with technical skill and genuine affection. His additional roles as a writer, critic, and man of cultural interests round out the portrait of a versatile and engaged individual. Through works like Sosta dei cacciatori, Donna in Lettura, and his numerous landscapes, Eugenio Cecconi continues to speak to audiences with his enduring vision of Tuscan light and life. His contribution remains a vital part of the rich tapestry of Italian art history.