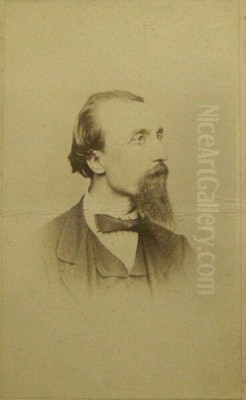

Vincenzo Cabianca stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century Italian art. Born in Verona in 1827 and passing away in Rome in 1902, Cabianca was an Italian painter whose career unfolded during a period of profound political and artistic transformation in Italy. He is primarily celebrated for his pivotal role within the Macchiaioli movement, a group of artists who revolutionized Italian painting by rejecting academic conventions and embracing realism, particularly through the innovative use of light and colour.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Vincenzo Cabianca's journey into the world of art began in his birthplace, Verona, a city then under Austrian rule but rich in artistic heritage. He pursued formal artistic training, initially enrolling at the Verona Academy of Fine Arts. His education continued at the prestigious Venice Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia). During these formative years, he would have been immersed in the traditional academic curriculum, focusing on drawing, perspective, and the study of Old Masters.

However, the artistic and political ferment of the time undoubtedly influenced the young painter. While his early work might have shown leanings towards landscape painting within accepted norms, the seeds of dissatisfaction with rigid academicism were likely sown during this period. Venice, with its unique light and atmosphere, may have also begun to shape his sensitivity to tonal values and atmospheric effects, elements that would become central to his mature style.

Florence and the Caffè Michelangelo

A pivotal moment in Cabianca's life and career occurred around 1853 when he moved to Florence. This city was not just the historical heart of the Italian Renaissance; in the mid-19th century, it was a vibrant center for artists and intellectuals seeking change. Cabianca soon became associated with the group of artists who frequented the Caffè Michelangelo, a modest establishment in Florence that served as the crucible for the Macchiaioli movement.

Here, amidst lively discussions about art, politics, and the future of Italy, Cabianca found kindred spirits. He formed a close friendship with Telemaco Signorini, a leading figure and articulate spokesman for the group. Other prominent artists he interacted with included Giovanni Fattori, Silvestro Lega, Odoardo Borrani, Cristiano Banti, and Serafino de Tivoli. This environment proved transformative. Influenced by Signorini and the collective spirit of rebellion against the establishment, Cabianca shifted decisively away from conventional landscape painting towards a more robust, realistic style grounded in direct observation.

The Macchiaioli Movement: Context and Principles

The Macchiaioli represented a radical departure from the prevailing artistic norms in Italy, which were dominated by Neoclassicism and Romanticism taught in the academies. The name "Macchiaioli," initially used derisively by a critic, derives from the Italian word "macchia," meaning "patch" or "stain." It referred to the artists' practice of using distinct patches of colour and chiaroscuro (light and shadow) to construct form and capture the immediate impression of a scene, often painted outdoors (plein air).

This group sought verismo – a truthful depiction of reality, focusing on contemporary Italian life and landscapes rather than historical or mythological subjects. They believed that the impression of light was the primary element conveying reality. By juxtaposing areas of light and shadow, often with strong tonal contrasts, they aimed to capture the essence of a subject with freshness and immediacy. Their approach paralleled, and in some ways anticipated, developments in France with the Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and later, the Impressionists such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas, though the Macchiaioli developed their style independently.

Crucially, the Macchiaioli movement was deeply intertwined with the Risorgimento, the struggle for Italian unification and independence. Their focus on authentic Italian scenes – Tuscan countryside, peasant life, soldiers – was a form of cultural nationalism, an effort to forge a distinctly Italian modern art identity, free from foreign dominance and academic stagnation.

Cabianca's Artistic Style: Light, Shadow, and Realism

Vincenzo Cabianca became one of the most distinctive interpreters of the macchia technique. His work is characterized by a profound sensitivity to light and its effects. He was particularly drawn to dramatic lighting conditions – the stark contrasts of midday sun, the soft glow of twilight, the ethereal quality of moonlight. He used bold patches of colour and strong tonal oppositions to render these effects, simplifying forms to their essential masses.

His brushwork was often vigorous and direct, contributing to the sense of immediacy. While committed to realism, his paintings often possess a strong poetic and sometimes melancholic atmosphere, derived from his handling of light and his choice of subjects. He frequently depicted the Tuscan landscape, scenes of rural labor, and quiet moments of daily life. Figures in his paintings, whether peasants, nuns, or townspeople, are rendered with dignity and psychological insight, integrated naturally within their environment.

Cabianca excelled in capturing specific times of day and weather conditions, demonstrating a keen observational skill honed through plein air practice. His compositions are often carefully structured, using light and shadow not just for realistic effect but also to create mood and guide the viewer's eye. He explored various themes, moving fluidly between landscapes, genre scenes, and occasionally, subjects with historical or religious undertones, always filtered through his unique stylistic lens.

Key Works and Themes

Cabianca's oeuvre includes several works that are considered landmarks of the Macchiaioli movement and Italian 19th-century art.

One of his most celebrated paintings is Le monachelle (often translated as The Nuns or Little Nuns), typically dated to the early 1860s. This work depicts nuns walking along a sun-drenched wall. The brilliance of the sunlight on the white habits and the wall contrasts sharply with the deep shadows, creating a powerful visual impact. The painting is a masterful study in light and form, using the macchia technique to great effect, while also conveying a sense of quiet contemplation and seclusion.

Ritorno dai campi (Return from the Fields, 1862) exemplifies Cabianca's interest in rural life. It portrays peasants returning home, likely in the evening light. The work captures the atmosphere of the Tuscan countryside and the simple dignity of its inhabitants, rendered with the characteristic patches of colour and attention to light that define the Macchiaioli style.

Works like Al sole (In the Sun, 1866) and Il pastore (The Shepherd, 1866) further demonstrate his commitment to painting contemporary reality and his fascination with the effects of strong sunlight. These paintings often feature figures integrated into landscapes bathed in intense light, showcasing the bold contrasts and simplified forms typical of his approach during this period.

Chiesa di San Pietro (Church of San Pietro, 1860) shows his ability to apply the macchia technique to architectural subjects, focusing on how light interacts with stone surfaces. Other notable works often mentioned include depictions of twilight, such as Campanian Twilight, and scenes from Venice, like Venetian Boatwomen, highlighting his versatility in subject matter while maintaining his stylistic focus on light. Later in his career, Cabianca also produced accomplished works in watercolour, often characterized by a more delicate handling of light and atmosphere.

Contemporaries and Collaborations

Cabianca's artistic development was deeply influenced by his interactions with fellow artists. His friendship with Telemaco Signorini was particularly significant, providing intellectual stimulus and shared artistic goals. He was an integral part of the Macchiaioli collective, contributing to their exhibitions and discussions.

He worked alongside Giovanni Fattori, known for his depictions of military life, Maremma landscapes, and agricultural scenes; and Silvestro Lega, celebrated for his intimate portrayals of middle-class domestic life, often set in sunlit gardens or interiors. Other key figures in his circle included Odoardo Borrani, who shared an interest in realistic genre scenes, and Cristiano Banti, a fellow explorer of light effects and rural themes.

The broader Macchiaioli group included talents like Giuseppe Abbati, admired for his paintings of cloisters and interiors before his untimely death; Vito D'Ancona, known for his portraits and later engagement with Orientalist themes; and Raffaello Sernesi, another promising artist who died young as a result of wounds sustained fighting with Garibaldi. The critic Diego Martelli was the primary theorist and supporter of the group, hosting many of the artists at his estate in Castiglioncello. Figures like Nino Costa (Giovanni Costa), who bridged Italian and English art circles, and the sculptor/painter Adriano Cecioni were also associated with the movement, contributing to the rich artistic dialogue of the era. Cabianca's engagement with these diverse talents fostered a dynamic environment of experimentation and mutual influence.

Political Engagement and the Risorgimento

Like many of his Macchiaioli colleagues, Vincenzo Cabianca was a fervent patriot, deeply committed to the cause of Italian unification and independence – the Risorgimento. His move to Florence coincided with a period of intense political activity aimed at liberating Italian territories from foreign control (primarily Austrian) and unifying the peninsula under an Italian government.

Sources suggest Cabianca actively participated in the movement. There are accounts linking him to revolutionary activities, possibly including involvement in the defense of Bologna during uprisings, which may have precipitated his move to the relative safety of Florence. Some sources even mention a period of arrest due to his political engagement.

This patriotic fervor permeated his art. While he didn't focus heavily on overt battle scenes like Fattori sometimes did, his choice to depict contemporary Italian life and landscapes was itself a political act. It represented a turning away from the idealized, often foreign-inspired subjects favored by the academies, and an embrace of Italy's own reality and identity. His paintings contributed to the cultural project of building a modern, unified Italian nation by celebrating its land and people.

Later Career and Recognition

In the later decades of his career, Cabianca eventually moved from Florence to Rome, which had become the capital of unified Italy in 1871. He continued to paint and exhibit his work. While perhaps less intensely involved in the collective activities of the Macchiaioli (as the group itself evolved and dispersed), he maintained his distinctive style, though some evolution is noticeable, particularly a greater exploration of watercolour.

He participated in various exhibitions, including significant shows in Venice, where his work was recognized. For instance, his paintings were featured in exhibitions showcasing new trends in Venetian art circles. His reputation as a leading figure of the Macchiaioli was solidified during his lifetime.

However, like many artists, he may have faced challenges later in life. Some accounts suggest a possible decline in demand for his specific style or perhaps economic difficulties, though details remain scarce. Regardless of any later struggles, his contribution to Italian art had already secured his place in its history. He passed away in Rome in 1902.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Vincenzo Cabianca is regarded by art historians as one of the most original and significant members of the Macchiaioli movement. His unique sensitivity to light and shadow, combined with his commitment to realism and his innovative use of the macchia technique, place him at the forefront of the revolution against academic painting in 19th-century Italy.

His work represents a crucial bridge between traditional Italian landscape painting and modern European art movements. While distinctly Italian and tied to the specific context of the Risorgimento, his experiments with light, colour, and plein air painting resonate with broader trends that led towards Impressionism.

Today, his paintings are held in major Italian museums, including the Galleria d'Arte Moderna at the Pitti Palace in Florence and the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Moderna e Contemporanea in Rome, as well as other public and private collections. He is consistently featured in exhibitions dedicated to the Macchiaioli and 19th-century Italian art. His historical evaluation remains high; he is recognized not only for his technical skill and aesthetic vision but also for his role in shaping a modern artistic identity for Italy. His ability to infuse realistic scenes with poetic feeling and dramatic intensity through his mastery of light remains his most enduring legacy.

Conclusion

Vincenzo Cabianca was more than just a painter; he was an innovator and a patriot whose art reflected the turbulent and transformative era in which he lived. As a core member of the Macchiaioli, he helped dismantle the constraints of academic tradition, pioneering a new way of seeing and representing the world based on direct observation, truthfulness, and the powerful effects of light and shadow. His evocative depictions of Italian landscapes and daily life, rendered with bold technique and profound sensitivity, continue to resonate, securing his position as a pivotal figure in the history of modern Italian art.