Fannie Moody stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of British art, particularly within the popular Victorian and Edwardian genre of animal painting. Active during a period when the depiction of domestic animals, especially dogs, reached a zenith of public affection, Moody carved a niche for herself with works characterized by their warmth, humour, and keen observation of animal behaviour. Her art provides a delightful window into the era's fondness for pets, rendered with a skill that, while largely self-cultivated, resonated with audiences and critics alike.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1861 in the United Kingdom, Fannie Moody entered a world where art was undergoing significant shifts, yet traditional genres like animal painting retained a strong appeal. She was the daughter of Francis Wollaston Moody (1824-1886), an artist and instructor associated with the South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert Museum), who was known for his decorative work and art theory. Growing up in an artistic household likely provided an environment conducive to her own burgeoning talents, offering early exposure to the principles of art and design, even if formal instruction from her father is not extensively documented.

The Victorian era was a fertile ground for artists interested in the natural world. The public's fascination with animals, fueled by scientific exploration, the rise of pet ownership among the burgeoning middle class, and a sentimental attachment to domestic creatures, created a demand for animal portraiture and genre scenes. Artists like Sir Edwin Landseer had already elevated animal painting to a high art form, imbuing his subjects with almost human-like emotions and narratives, which deeply appealed to Victorian sensibilities. It was within this cultural milieu that Fannie Moody would develop her artistic voice.

A Largely Self-Taught Path

While many aspiring artists of her time sought rigorous academic training, Fannie Moody’s journey was predominantly one of self-instruction. This path was not uncommon, especially for women artists who often faced greater barriers to accessing formal art education, particularly life drawing classes which were considered essential. However, Moody did receive some guidance from John Trivett Nettleship (1841-1902), an accomplished animal painter in his own right, known for his powerful depictions of wild animals and his association with literary figures like Robert Browning.

Nettleship's influence, though perhaps not extensive in terms of formal tutelage, would have been valuable. He was an artist who understood animal anatomy and behaviour, and his own work often conveyed a sense of the wild spirit of his subjects. Any instruction from him would have likely emphasized keen observation and anatomical accuracy, elements that are discernible in Moody's work, albeit applied to more domestic and lighthearted themes. Her ability to capture the characteristic poses and expressions of dogs suggests a dedicated study of her subjects, a hallmark of a committed animalier.

Artistic Style: Humour and Vivacity

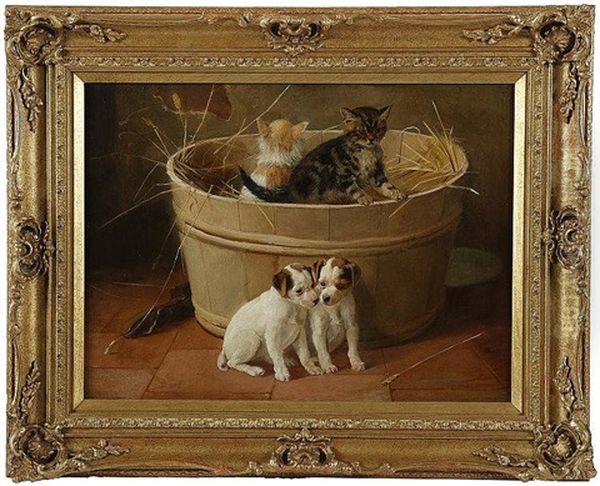

Fannie Moody’s artistic signature lies in her ability to infuse her animal subjects, particularly dogs, with a sense of humour, vivacity, and narrative charm. Her paintings often depict playful or mischievous scenarios, capturing moments of everyday animal life that resonate with pet lovers. Unlike the grand, often moralizing, canvases of some of her contemporaries, Moody’s works tend to be more intimate and anecdotal, focusing on the endearing qualities of her subjects.

Her style is characterized by a competent, if not overtly flamboyant, technique. She paid close attention to the texture of fur, the expressiveness of eyes, and the dynamic postures of animals in motion or interaction. Her compositions are generally straightforward, designed to highlight the central animal characters and their story. The humour in her work is gentle and observational, stemming from a genuine affection and understanding of animal behaviour rather than forced anthropomorphism, although a degree of human-like emotion is often implied, as was common in the period. This approach made her work accessible and appealing to a broad audience.

"Stolen Milk is Sweetest": A Representative Work

Among her known works, the illustration "Stolen Milk is Sweetest," dated 1908, serves as an excellent example of her thematic concerns and artistic style. This piece vividly portrays a common domestic drama: a cat attempting to reclaim a bowl of milk from a rather cheeky dog who has clearly helped itself. The scene is alive with implied action and character. The dog's posture might suggest a playful defiance or a moment of being caught in the act, while the cat's stance would convey its indignation or determination.

Such a work encapsulates Moody's strengths: her ability to tell a small story, to capture the distinct personalities of different animal species, and to create a scene that is both amusing and relatable. The title itself adds to the charm, reflecting a popular adage and inviting the viewer to smile at the familiar antics of household pets. This painting, like many of her others, would have appealed to the Victorian and Edwardian love for narrative art and their sentimental attachment to domestic animals.

Exhibitions and Professional Affiliations

Fannie Moody achieved a notable degree of professional recognition during her career. She exhibited her works at prestigious venues, most significantly at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Her paintings were shown there between 1888 and 1897, a period that marks a significant phase of her public career. To have work accepted and displayed at the Royal Academy was a considerable achievement, indicating a level of skill and appeal that met the standards of the leading art institution of the day.

Furthermore, Moody was a member of the Society of British Artists (now the Royal Society of British Artists, RBA), a significant exhibiting society that provided an alternative venue to the Royal Academy and supported a wide range of artists. She was also a member of the Society of Women Artists (SWA). The SWA, founded in 1855, played a crucial role in providing exhibition opportunities and professional support for women artists at a time when they faced considerable challenges in the male-dominated art world. Her involvement with these societies underscores her active participation in the London art scene.

The Context of Victorian Animal Painting

Fannie Moody worked within a vibrant and popular tradition of animal painting in Britain. The 19th century saw an explosion in this genre, with artists catering to diverse tastes, from the aristocratic patrons of sporting art to the middle-class desire for charming domestic scenes. The towering figure of Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) dominated the first half of the century, his works like "The Monarch of the Glen" and "Dignity and Impudence" becoming iconic. Landseer's ability to imbue animals with human-like emotions and narratives set a standard, though later artists explored different facets of animal life.

Other notable animal painters of the era, or those whose careers overlapped with Moody's, include Briton Rivière (1840-1920), known for his dramatic and often poignant depictions of animals, sometimes with classical or biblical themes, such as "Daniel's Answer to the King." John Emms (1843-1912) was renowned for his vigorous and characterful paintings of hounds and terriers, often capturing them with a directness and lack of sentimentality that appealed to sporting enthusiasts. His style was robust and painterly.

Maud Earl (1864-1943) was a contemporary of Fannie Moody and another successful female animal painter, particularly celebrated for her portraits of purebred dogs. Earl's work was often more formal and focused on the specific characteristics of different breeds, catering to the growing interest in dog shows and pedigree. Her international career, including time in America, highlights the widespread appeal of canine portraiture.

The tradition also included artists like Richard Ansdell (1815-1885), who, like Landseer, painted animals in grand landscapes and sporting scenes, and Heywood Hardy (1842-1933), whose work spanned animal subjects, sporting art, and 18th-century genre scenes. Arthur Wardle (1860-1949), another contemporary, was a prolific and versatile painter of animals, from domestic pets to exotic wildlife, known for his anatomical accuracy and vibrant style.

Earlier figures who laid the groundwork for this tradition include George Stubbs (1724-1806), whose mastery of equine anatomy was unparalleled, and John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865), famous for his coaching scenes and portraits of racehorses. Even landscape painters like Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902), known as 'Cow Cooper' for his ubiquitous depictions of cattle and sheep in idyllic pastoral settings, contributed to the public's appreciation for animal subjects in art. Across the Channel, the French artist Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899) achieved immense international fame for her powerful animal paintings, such as "The Horse Fair," demonstrating that female artists could excel in this demanding genre. Fannie Moody's work, with its focus on humorous and anecdotal dog paintings, found its own distinct place within this diverse and popular field.

Women Artists in the Victorian Era: Challenges and Triumphs

Fannie Moody's career also needs to be understood in the context of the opportunities and limitations faced by women artists in the Victorian and Edwardian periods. While women had always been involved in art, the 19th century saw a significant increase in the number of women pursuing art professionally. However, they often encountered systemic obstacles. Access to formal training, particularly life drawing from the nude model (considered essential for history painting and complex figure compositions), was restricted or segregated.

Institutions like the Royal Academy Schools were slow to admit women on equal terms with men. Consequently, many women artists, like Moody, were partly or wholly self-taught, or received private tuition. Others attended newly established art schools for women, such as the Slade School of Fine Art, which was more progressive in its admission policies. Despite these challenges, many women achieved considerable success.

The Society of Women Artists (SWA), of which Moody was a member, provided a vital platform. It allowed women to exhibit and sell their work, network with peers, and gain professional recognition outside the often male-dominated structures of institutions like the Royal Academy. Genre painting, portraiture, flower painting, and animal painting were considered more "appropriate" for women artists by societal standards, and many women excelled in these areas. Artists like Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler) (1846-1933) broke barriers by achieving fame with large-scale military paintings, a traditionally male domain. Kate Greenaway (1846-1901) became immensely popular for her charming illustrations of children, while Helen Allingham (1848-1926) was celebrated for her idyllic watercolour depictions of rural cottages and gardens.

Other notable female contemporaries included Louise Jopling (1843-1933), a versatile painter of portraits, genre scenes, and aesthetic subjects, who also wrote a guide for aspiring female artists. In a slightly different vein, Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) pursued a more allegorical and spiritual path, influenced by Pre-Raphaelitism and Symbolism. Fannie Moody's success in animal painting, therefore, was part of a broader movement of women asserting their place in the professional art world, often by excelling in genres that allowed them to showcase their unique perspectives and talents.

Later Life and Legacy

Fannie Moody continued to work into the 20th century, with "Stolen Milk is Sweetest" dated 1908, indicating her activity well into the Edwardian era. She passed away in 1948. While she may not have achieved the same level of enduring fame as some of her male counterparts or pioneering female artists in other genres, her contribution to animal painting is significant. Her work reflects a genuine affection for her subjects and a talent for capturing their character in an engaging and accessible manner.

Her paintings are part of a broader cultural phenomenon: the Victorian and Edwardian embrace of the domestic pet as a cherished member of the household. Her art celebrated the everyday interactions and humorous incidents that define the relationship between humans and their animal companions. In this, she tapped into a sentiment that remains potent today, ensuring that her charming vignettes of animal life continue to find an appreciative audience.

Fannie Moody's legacy is that of a skilled and observant animalier who brought a lighthearted touch to her chosen genre. Her works offer a glimpse into the social history of pet ownership and the enduring appeal of animal companionship. As a female artist who navigated the professional art world of her time, exhibiting at major venues and belonging to important artistic societies, she also represents the growing presence and contribution of women in the arts during a period of significant social and cultural change. Her charming and often humorous depictions of dogs and other animals remain a testament to her specific talent and her place within the tradition of British animal art.