William Oliver Williams stands as a notable figure within the rich tapestry of 19th-century British art. Active during the Victorian era, he carved a niche for himself as a figurative painter, celebrated particularly for his depictions of young women, often adorned in the elegant drapery of classical Greek or Roman attire. His life, spanning from 1823 to 1901, coincided with a period of significant artistic production and shifting aesthetic values in Britain.

Understanding Williams requires navigating a point of potential confusion regarding his name. He frequently signed his works simply as "William Oliver." This practice led to his being mistaken, both during his lifetime and subsequently, for other individuals bearing the same name. Most notably, he is often confused with William Oliver (1804-1853), a landscape painter, and Dr. William Oliver (1695-1764), a physician famed as the inventor of the Bath Oliver biscuit. It is crucial to distinguish William Oliver Williams, the figurative artist born in 1823, from these other historical figures.

Formative Years and Academic Foundations

William Oliver Williams was born in Worcester, England, in 1823. His background was rooted in the professional middle class; his father, William Williams, was a surgeon, and his mother was Jane Williams (née Oliver). This connection through his mother's maiden name likely contributed to his later use of "William Oliver" as a professional signature, adding another layer to the naming complexities surrounding his career.

His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the epicentre of artistic education and exhibition in Britain at the time. Williams proved to be a capable student, demonstrating considerable talent. His dedication culminated in a significant early achievement: in 1851, he was awarded the first prize for painting, signalling his promise and technical proficiency within the highly competitive academic environment.

Italian Sojourn and the Arundel Society Commission

Like many aspiring British artists of his generation, Williams sought inspiration and further refinement of his skills by travelling abroad. In the early 1850s, he journeyed to Italy, the historical heartland of classical antiquity and Renaissance mastery. This period was crucial for immersing himself in the works of the Old Masters and absorbing the aesthetics of the Italian landscape and culture, influences that would subtly permeate his later work.

During his time in Italy, Williams undertook a significant commission for the Arundel Society. This influential organization, founded in 1849, aimed to promote knowledge of early European art, particularly Italian frescoes, by publishing high-quality reproductions. Williams was tasked with creating detailed drawings of the famed frescoes by Giotto di Bondone in the Arena (Scrovegni) Chapel in Padua. This was exacting work, requiring precision and sensitivity to capture the essence of these early Renaissance masterpieces.

His contribution to the Arundel Society's project was valuable. Three of the drawings he produced during this commission have survived and are now held in the esteemed collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. This work not only honed his draughtsmanship but also connected him to a major project dedicated to art historical preservation and dissemination, aligning him with figures interested in the revival and appreciation of earlier art forms.

Defining an Artistic Vision: Style and Subject Matter

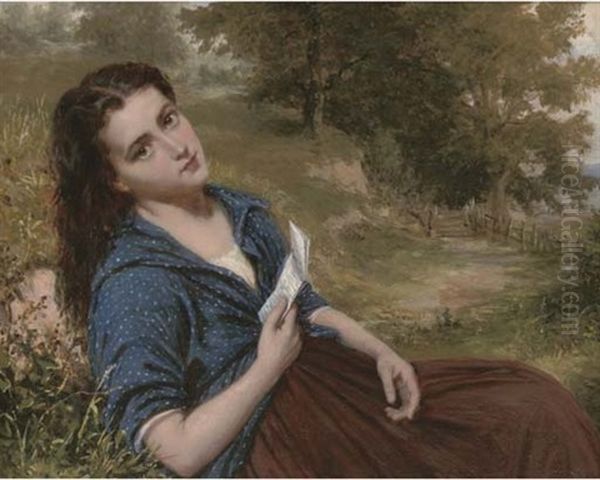

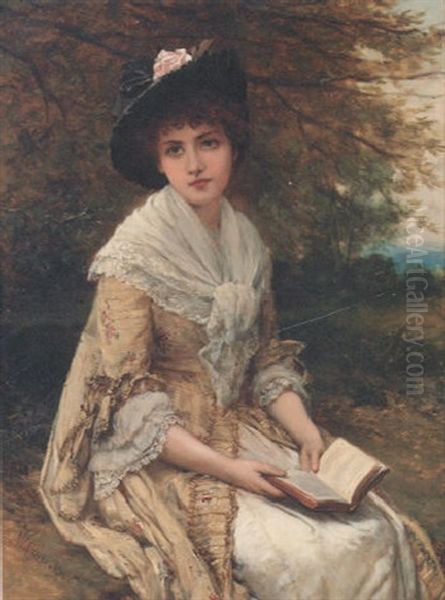

William Oliver Williams developed a distinct artistic identity centred on figurative painting. His primary and most celebrated subjects were young women. He depicted them with a characteristic grace and elegance, often capturing moments of quiet contemplation or gentle activity. His portrayals frequently featured classical elements, particularly in the flowing robes reminiscent of Greek or Roman statuary, lending an air of timeless beauty to his Victorian subjects.

His style can be characterized as refined and detailed, adhering to the academic standards of finish prevalent during the era. He possessed a keen eye for fabric textures and the play of light, rendering his subjects with sensitivity and charm. While often idealized, his figures convey a sense of personality and presence. Works such as "A Bouquet of Roses," depicting a young woman holding flowers, exemplify his focus on feminine grace and the integration of natural elements.

Another notable work, "Reclining Beauty," further showcases his skill in portraying the female form with elegance and technical assurance. His paintings often evoke a sense of romanticism, filtered through a distinctly Victorian lens. He favoured compositions that were balanced and harmonious, emphasizing beauty and decorum. His consistent focus on these themes established him as a reliable producer of appealing figurative works that found favour with the contemporary audience.

Exhibition Career and Professional Recognition

Throughout his career, William Oliver Williams actively sought to bring his work before the public eye by participating in major exhibitions. He submitted paintings to the Royal Academy's prestigious Summer Exhibition on multiple occasions. Records indicate he exhibited there six times between 1858 and 1882, a significant achievement given the competitive nature of the selection process. Showing at the RA was crucial for an artist's reputation and commercial success.

Beyond the Royal Academy, Williams also exhibited his works at other important venues. These included the Royal Society of British Artists (RBA) on Suffolk Street, London, and the Birmingham Society of Artists. Consistent participation in these exhibitions ensured his visibility within the national art scene and helped to build his reputation among collectors, critics, and fellow artists. His presence in these shows placed him firmly within the mainstream of Victorian art production.

The inclusion of his works in these exhibitions underscores their alignment with prevailing tastes. His elegant depictions of women, often imbued with a gentle sentimentality or classical allusion, resonated with Victorian audiences who appreciated technical skill, narrative clarity, and idealized beauty. His exhibition record confirms his status as a recognized professional artist of his time.

Navigating Identity: The William Oliver Conundrum

The persistent confusion surrounding William Oliver Williams' name warrants specific attention. His decision to sign his work as "William Oliver" created an ambiguity that has echoed through art historical records and the art market. It is essential to reiterate the distinctions between the key figures involved.

Firstly, there is William Oliver Williams (1823-1901), the subject of this discussion. He was the figurative painter known for his portrayals of women, often in classical dress, who studied at the RA Schools, worked for the Arundel Society, and exhibited widely. His work is characterized by its Victorian elegance and figurative focus.

Secondly, there is William Oliver (1804-1853). This William Oliver was primarily a landscape painter. He travelled extensively on the continent and produced views of European scenery as well as English landscapes. His style and subject matter are distinctly different from those of Williams. The overlap in name and near-contemporary period has been a primary source of confusion.

Thirdly, there is Dr. William Oliver (1695-1764). This individual belongs to an earlier era and a different field entirely. He was a prominent physician in Bath, known for his medical work and, perhaps more famously today, as the inventor of the Bath Oliver digestive biscuit. He has no direct connection to the art world of William Oliver Williams. Clarifying these identities is crucial for accurate attribution and understanding of Williams' specific artistic contribution.

A Role in Art Education

Beyond his own studio practice, William Oliver Williams also contributed to the field of art education. He held teaching positions that allowed him to pass on his skills and knowledge to younger generations of artists. Notably, he served as an Assistant Master at the Birmingham School of Design. This institution played a vital role in training artists and designers in the industrial heartland of England.

Furthermore, Williams also held a position as a lecturer at the Royal Academy in London. Teaching at the RA Schools was a mark of distinction, indicating recognition of his expertise by the foremost art institution in the country. His involvement in teaching suggests a commitment to the academic principles he himself had learned and practiced. Through these roles, he would have influenced students and contributed to the continuity of artistic training in Britain during the latter half of the 19th century.

The Victorian Art Scene: Context and Contemporaries

To fully appreciate William Oliver Williams' place in art history, it is helpful to consider the broader context of the Victorian art world in which he operated. This era was marked by the dominance of the Royal Academy, a taste for narrative and anecdotal painting, and a complex interplay between academic tradition, burgeoning realism, and aesthetic experimentation. Williams worked alongside numerous other artists, each contributing to the period's diverse artistic landscape.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded in 1848 by figures like Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt, challenged academic conventions with their emphasis on intense detail, vibrant colour, and subjects drawn from literature and medieval history. While Williams shared a commitment to detailed rendering, his style remained more aligned with classical grace than Pre-Raphaelite intensity.

Grand classical themes and depictions of idealized beauty were masterfully handled by leading Academicians such as Lord Frederic Leighton and Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Their elaborate reconstructions of ancient life, often featuring languid female figures, represent a more opulent and scholarly strand of classicism than Williams' gentler interpretations. Yet, the shared interest in classical motifs connects them.

Portraiture remained a vital genre, practiced by artists like George Frederic Watts, known for his "Hall of Fame" portraits of eminent Victorians, and Sir Francis Grant, who served as President of the Royal Academy. Genre painting, depicting scenes of everyday life, was immensely popular, with artists like William Powell Frith capturing sprawling contemporary scenes, and George Elgar Hicks portraying domestic moments. James Tissot, though French, spent a significant period in London, depicting scenes of fashionable modern life.

Later in the century, artists associated with the Aesthetic Movement, such as Albert Moore and Edward Burne-Jones (also linked to the later phase of Pre-Raphaelitism), explored beauty for its own sake, often using classical figures in decorative compositions. Mythological and romantic subjects featuring compelling female figures continued with artists like John William Waterhouse. Even the towering figures of British landscape painting, John Constable and J.M.W. Turner, though preceding Williams' main period, cast a long shadow over the artistic landscape. Mentioning contemporaries like John Brett, known for his detailed coastal scenes, further illustrates the period's diversity. Williams navigated this complex scene, finding his niche in refined figurative work.

Later Life and Legacy

William Oliver Williams continued to paint throughout his later years, maintaining his focus on the subjects and style that had defined his career. He passed away in 1901, at the very end of the Victorian era. His work remains represented in public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum (notably the Arundel Society drawings) and the Manchester Art Gallery, ensuring his contribution is not entirely forgotten.

His historical evaluation places him as a competent and appealing painter within the Victorian academic tradition. While not considered a major innovator who drastically altered the course of art history, he excelled within his chosen genre. His legacy lies in his sensitive and graceful portrayals of young women, capturing a specific Victorian ideal of femininity and beauty. His works serve as valuable examples of the period's tastes and artistic standards.

The confusion surrounding his name has perhaps somewhat obscured his individual identity in art historical accounts, making careful attribution essential. Nevertheless, his paintings continue to appear on the art market, appreciated by collectors for their charm, technical skill, and representation of Victorian aesthetic sensibilities. He remains a noteworthy figure among the many artists who shaped the visual culture of 19th-century Britain.

Beyond the Easel: Glimpses of Personal Life

While detailed accounts of William Oliver Williams' personal life are scarce compared to information about his artistic output, a few fragments offer glimpses beyond the studio. The provided source material mentions his involvement in illustration, specifically citing work for a book titled "Sailing in the City" . This suggests a versatility extending beyond easel painting, engaging with the burgeoning field of published illustration common in the Victorian era.

Another anecdote places him in a social setting, mentioning him riding on horseback to visit the Boscawitz family for tea and interacting with the sisters of the household. While minor, such details humanize the artist, reminding us of the social life that existed alongside professional duties. These snippets, though limited, hint at a life integrated within the social fabric of his time, involving activities and connections beyond his artistic practice.

Conclusion: A Victorian Vision

William Oliver Williams (1823-1901) occupies a specific and respectable place in the annals of British Victorian art. As a figurative painter, he dedicated his career primarily to the depiction of young women, often rendered with classical grace and attire, embodying the aesthetic ideals of his time. Trained at the Royal Academy Schools and active in major exhibitions, he was a recognized professional within the art establishment.

His work for the Arundel Society in Italy demonstrated his skill and connection to the period's interest in historical art. Although persistently shadowed by name confusion with the landscape painter William Oliver and the physician Dr. William Oliver, Williams' artistic identity is distinct, characterized by elegance, refinement, and a focus on idealized femininity.

While perhaps not reaching the fame of contemporaries like Leighton, Millais, or Alma-Tadema, William Oliver Williams contributed significantly to the visual culture of the Victorian era through his appealing compositions and skilled execution. His paintings remain as testaments to his talent and offer valuable insights into the artistic tastes and representations of beauty prevalent in 19th-century Britain. He is best remembered as a chronicler of Victorian grace, capturing a gentle and idealized vision of womanhood.