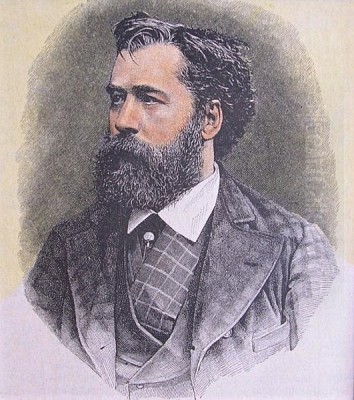

Ferdinand Knab (1834-1902) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in 19th-century German art. Primarily celebrated for his evocative landscape paintings, often imbued with architectural elements and a distinctively poetic atmosphere, Knab carved a unique niche for himself. His work masterfully blended meticulous observation with a romantic imagination, transporting viewers to worlds both ancient and dreamlike. This exploration delves into his life, artistic development, thematic preoccupations, and his position within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born on June 12, 1834, in Würzburg, Bavaria, Ferdinand Knab's artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age. His father was a painter, providing an immediate and immersive introduction to the world of art. This early exposure undoubtedly played a crucial role in shaping his future path, instilling in him a foundational understanding and appreciation for the visual arts.

Knab's formal artistic training, however, did not begin with painting. He initially pursued architecture, studying in Nuremberg under the guidance of Carl Alexander von Heideloff, a prominent architect and conservator known for his work in the Gothic Revival style. This architectural grounding would prove to be a defining characteristic of Knab's later painterly oeuvre. For two years, he engaged in practical architectural work, gaining firsthand experience with structure, form, and spatial composition.

This foundational period in architecture provided Knab with a unique perspective. Unlike artists who approach landscape or historical scenes purely from a painterly tradition, Knab brought an architect's eye for detail, an understanding of structural integrity, and a sensitivity to the interplay of light and shadow on built forms. This technical knowledge would later allow him to render ancient ruins and fantastical edifices with a convincing solidity, even within highly romanticized settings.

The Munich Years and a Shift to Painting

In 1859, Knab made a pivotal decision that would redirect his artistic trajectory. He moved to Munich, then a major artistic hub in Europe, to further his studies. While his architectural background remained influential, his focus shifted decisively towards painting, particularly architectural painting. This was a logical progression, allowing him to combine his passion for built environments with the expressive possibilities of the painted canvas.

In Munich, Knab sought instruction from some of the leading figures of the time. He became a student of Carl Theodor von Piloty (1826-1886), a highly influential historical painter and professor at the Munich Academy. Piloty was renowned for his large-scale, dramatic depictions of historical events, characterized by meticulous detail and theatrical compositions. Under Piloty, Knab would have been exposed to the principles of grand narrative painting and the importance of historical accuracy, albeit often filtered through a romantic lens.

Knab also studied with Arthur von Ramberg (1819-1875), an Austrian-born painter and illustrator who was also a professor at the Munich Academy. Ramberg was known for his genre scenes, literary illustrations, and frescoes, often displaying a lighter, more lyrical touch than Piloty. His influence might have encouraged Knab's poetic sensibilities and his interest in creating atmospheric moods. The combination of Piloty's dramatic historicism and Ramberg's lyrical genre work provided Knab with a rich and varied academic foundation.

It's important to note that the Munich Academy in the mid-19th century was a crucible of artistic ideas. While academic traditions were strong, there was also a growing interest in realism, landscape painting, and more personal forms of expression. Artists like Franz von Lenbach, known for his powerful portraits, and Wilhelm Leibl, a key figure in German Realism, were also part of this broader Munich scene, though their styles differed significantly from Knab's developing romanticism.

Artistic Style: Poetry, Symbolism, and the Architectural Soul

Ferdinand Knab's mature artistic style is characterized by a profound sense of poetry and symbolism. He was not merely a topographical painter of landscapes or a dry recorder of architectural structures. Instead, he sought to capture the soul of a place, often infusing his scenes with a romantic, sometimes melancholic, and frequently dramatic atmosphere.

His works are often described as anti-classical, moving away from the idealized, balanced compositions of Neoclassicism towards a more subjective and emotional engagement with the subject matter. Nature, in Knab's paintings, is rarely just a backdrop; it is an active participant, often vast and overwhelming, with human figures, if present, appearing small and contemplative. This approach aimed to guide the viewer towards a more spiritual or transcendental experience, reflecting a common thread in Romantic art, seen in the works of earlier masters like Caspar David Friedrich.

A defining feature of Knab's art is the seamless integration of architectural elements into his landscapes. These are not always real-world structures but often fantastical or idealized constructions, frequently featuring ruins. Roman ruins, in particular, held a strong fascination for him, a passion likely ignited or intensified by his travels. His 1868 journey to Italy, where he was captivated by the ancient wonders of Rome, was a significant turning point, leading him to increasingly feature ruins as central motifs.

These ruins in Knab's paintings are laden with symbolic meaning. They speak of the passage of time, the transience of empires, and the enduring power of nature. Yet, they are not always purely melancholic. Sometimes, they suggest a sense of nostalgia for a glorious past, or even a glimmer of hope, as if new life or understanding might emerge from the remnants of what once was. This duality reflects a broader 19th-century cultural preoccupation with history and the cyclical nature of civilizations.

Thematic Concerns: Ancient Wonders and Evocative Light

Knab's thematic repertoire extended beyond generic landscapes with ruins. He was drawn to depicting some of the legendary Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, allowing his architectural imagination full rein. His painting of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon (1886) is a prime example, a lush, fantastical vision of terraces, exotic flora, and grand structures, bathed in an ethereal light. He also created works inspired by the Colossus of Rhodes, further showcasing his interest in monumental, almost mythical, architecture.

The use of light is another crucial aspect of Knab's artistry. He was particularly adept at capturing the effects of twilight or dusk, often referred to by the German term "Abendlicht" (evening light). This crepuscular illumination imbues his scenes with a sense of mystery, tranquility, or impending drama. Colors become richer, shadows lengthen, and the overall mood is intensified. His work Roman Ruins in the Evening Light (Römische Ruine im Abendlicht, 1892) exemplifies this mastery, where the fading light casts a warm, melancholic glow over the ancient stones.

This preference for specific lighting conditions and atmospheric effects connects Knab to other Romantic landscape painters, such as the British master J.M.W. Turner, who also explored the expressive power of light and atmosphere, albeit with a different stylistic approach. Knab's meticulous rendering of architectural detail, however, often provided a more solid, tangible counterpoint to his atmospheric effects than Turner's more abstract visions.

Knab also valued the medium of watercolor, a medium often favored for its immediacy and ability to capture subtle atmospheric shifts. His proficiency in watercolor allowed him to create works of great delicacy and luminosity, complementing his more substantial oil paintings.

Patronage and Royal Commissions: King Ludwig II

A significant aspect of Ferdinand Knab's career was his association with King Ludwig II of Bavaria, the "Swan King" or "Fairy Tale King." Ludwig II was an eccentric and lavish patron of the arts, known for his passion for Wagnerian opera, French absolutism, and the construction of fantastical castles like Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Herrenchiemsee.

Knab served as a court painter to Ludwig II, a prestigious position that provided him with important commissions. He was tasked with creating decorative paintings for the King's ambitious projects. Among these were works for the Munich Residenz's Winter Garden, a spectacular glass-and-iron structure built on the palace roof, filled with exotic plants and elaborate scenery. Knab's paintings would have contributed to the immersive, theatrical environments that Ludwig II sought to create.

He also contributed to the decoration of Linderhof Palace, Ludwig's smallest but most opulent rococo-inspired retreat. The King's desire for dreamlike, historically-infused environments perfectly matched Knab's artistic inclinations. This patronage not only provided Knab with financial stability and recognition but also allowed him to work on a grand scale, creating immersive architectural fantasies that were integral to Ludwig's vision. Other artists and architects heavily involved in Ludwig's projects included Georg von Dollmann, the primary architect for Linderhof and Neuschwanstein, and Julius Hofmann, who succeeded Dollmann. Christian Jank, a theatrical scene painter, provided many of the initial design concepts for Neuschwanstein, highlighting the theatricality inherent in Ludwig's commissions. Knab's work fit well within this milieu of romantic historicism and theatrical grandeur.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Ferdinand Knab was an active member of the Munich artistic community. He was part of the Munich Artists' Association and the Würzburg Artists' Association, connecting him with a network of peers. Among his contemporaries and associates in these circles were figures like Heinz Schiestl, a sculptor and graphic artist, and the painter Carl Diem. Another contemporary German artist of note, though perhaps with a different stylistic focus, was Karl Hagemeister, known for his Impressionistic landscapes. Johann Carl Smirsch was another artist active in the same general period.

The Munich School of painting, during Knab's active years, was diverse. While Piloty represented a dominant trend of historical painting, other movements were also present. The influence of the Barbizon School from France was beginning to be felt, encouraging plein-air painting and a more naturalistic approach to landscape, though Knab's work remained more rooted in studio-based imaginative compositions.

His earlier, brief teaching stint (1860-1862) at the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School is also noteworthy. During this period, he reportedly collaborated with Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901), a Swiss Symbolist painter famous for his atmospheric, mythological scenes (such as "Isle of the Dead"), and the sculptor Reinhold Begas (1831-1911), a leading figure in German Neo-Baroque sculpture. Interaction with artists like Böcklin, whose work shares a certain dreamlike and symbolic quality with Knab's, could have been mutually influential, or at least indicative of shared artistic currents.

While Knab's style was distinctly his own, it resonated with the broader Romantic and Symbolist tendencies of the late 19th century. His emphasis on subjective experience, the evocative power of ruins, and the creation of dreamlike atmospheres aligned with a cultural mood that sought an escape from increasing industrialization and materialism, looking instead towards history, myth, and the sublime beauty of nature. Artists like Hans Makart in Vienna, with his opulent historical and allegorical paintings, also catered to a taste for the grand and the theatrical, a taste shared by patrons like Ludwig II.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Beyond the titles already mentioned, Knab's oeuvre includes a range of evocative landscapes and architectural fantasies.

Roman Ruins in the Evening Light (Römische Ruine im Abendlicht) (1892): This painting is a quintessential Knab work. It likely depicts an imagined or composite view of Roman ruins, bathed in the warm, melancholic glow of sunset. The architectural details would be rendered with care, but the overall mood would be one of quiet contemplation and the passage of time. The interplay of light and shadow across the crumbling stones and overgrown vegetation would be a key feature.

Hanging Gardens of Babylon (1886): As one of the Seven Wonders, this subject allowed Knab to unleash his architectural imagination. The painting would depict a monumental terraced structure, overflowing with lush greenery, perhaps with figures hinting at the opulence and mystery of the ancient Mesopotamian civilization. The lighting would likely be dramatic, enhancing the sense of wonder and exoticism.

Arcadian Landscape (Arcadische Landschaft) (1894): The theme of Arcadia, a mythical pastoral paradise, was popular in art. Knab's interpretation would likely feature an idealized landscape, perhaps with classical architectural elements like temples or pavilions, and figures enjoying a harmonious existence with nature. The mood would be serene and idyllic, a common Romantic yearning for a lost golden age.

Evening Palace Architecture on the Lake with Musicians (Abendliche Palast Architektur am See mit Musikern) (1892): This title suggests a scene of romantic elegance, combining Knab's love for architecture and atmospheric evening light. A grand palace, perhaps with fantastical elements, would be set against a tranquil lake, with the presence of musicians adding a touch of lyrical romanticism.

Landscape with Temple (Landschaft mit Tempel) (1887): Similar to the Arcadian theme, this work would likely feature a classical temple nestled within a picturesque landscape. The temple could be intact or a ruin, but its presence would evoke a sense of history, spirituality, and the classical ideal of beauty.

These works, and others like them, demonstrate Knab's consistent themes: the beauty of architecture (especially ancient or idealized), the evocative power of landscape, and the emotional impact of light and atmosphere. His paintings often function as "capriccios," architectural fantasies where real and imagined elements are combined to create picturesque compositions, a tradition that goes back to artists like Giovanni Paolo Panini and Hubert Robert.

Later Life, Legacy, and Collections

Ferdinand Knab continued to paint and exhibit his work throughout his life. His personality was described as direct, and while he made friends easily, these friendships were often said to be short-lived, with more profound connections forming later in his life. He passed away in Munich on November 3, 1902.

Historically, Knab is positioned as an artist who bridged late Romanticism with emerging Symbolist tendencies. His work reflects the 19th-century fascination with history, the exotic, and the subjective experience of the world. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his contemporaries, his contribution to German art, particularly in the realm of architectural landscape painting, is significant.

His initial training in architecture provided a distinct advantage, lending a structural credibility to even his most imaginative compositions. He successfully translated the grandeur and romance of historical and mythical architecture onto canvas, creating works that were both visually captivating and emotionally resonant.

Today, Ferdinand Knab's works are found primarily in private collections. They appear periodically at auctions, where they are appreciated by collectors of 19th-century European art. While major museum retrospectives may be infrequent, his paintings are represented in various public digital archives, such as Wikimedia Commons, allowing broader access to his imagery. Some of his decorative works created for Ludwig II can, in a sense, still be experienced within the context of the King's palaces, contributing to the overall artistic vision of those unique architectural ensembles. Exhibitions like those at the Cercle Artistique during his lifetime would have provided platforms for his work to be seen and appreciated by the public and fellow artists.

Conclusion: An Enduring Romantic Vision

Ferdinand Knab was an artist of considerable skill and a unique vision. His ability to fuse architectural precision with romantic sensibility created a body of work that continues to enchant. He masterfully captured the poetic essence of ruins, the grandeur of ancient wonders, and the subtle moods of landscapes under evocative light. As a court painter to King Ludwig II, he contributed to some of the most fantastical architectural projects of the 19th century, leaving his mark on the cultural landscape of Bavaria.

While he operated within the broader currents of 19th-century German art, alongside figures ranging from the historical painter Carl Theodor von Piloty to the symbolist Arnold Böcklin and landscape artists influenced by earlier masters like Caspar David Friedrich or contemporary movements, Knab cultivated a distinctive style. His paintings invite viewers into a world where history, myth, and nature converge, rendered with an architect's understanding and a poet's heart. His legacy is that of a romantic visionary who saw in stone and sky the enduring drama of time and the timeless appeal of beauty.