Fernand Maillaud stands as a significant figure in French art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Mouhet, Indre, on December 12, 1862, and passing away in Paris on June 30, 1948, Maillaud dedicated his artistic life to capturing the essence of rural France, particularly the landscapes and life of the Berry region and the Creuse valley. His work, deeply rooted in the observation of nature and provincial life, navigates the currents between Post-Impressionism and Symbolism, offering a unique vision that continues to resonate. Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Maillaud also distinguished himself in the decorative arts, collaborating with his wife on furniture and tapestry designs that gained international recognition. His journey from a modest background to becoming a respected member of the French art establishment is a testament to his dedication and singular artistic vision.

Humble Beginnings and Artistic Awakening

Fernand Maillaud's origins were modest, a factor that arguably shaped his perspective and thematic choices throughout his career. Born into the family of a carpenter, with his mother working as a teacher, he did not have the immediate access to artistic circles that some of his contemporaries enjoyed. This background perhaps fostered a closer connection to the working life and natural rhythms of the countryside that he would later depict with such empathy. His initial artistic inclinations were nurtured through self-teaching, a path driven by innate passion rather than formal privilege. This period of self-discovery laid the foundation for his later, more structured studies.

The decision to pursue art professionally led him to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. France in the late 19th century was a place of immense social and cultural change. Industrialization was transforming urban centers, yet a deep attachment to the land and regional traditions persisted, often idealized in art and literature. Maillaud arrived in this dynamic environment, seeking to hone his skills and find his voice amidst the competing artistic ideologies, from the lingering influence of academicism to the revolutionary waves of Impressionism and its successors.

Formal Training and Early Influences

Despite his initial self-directed learning, Maillaud understood the value of formal instruction. He sought training in Paris, notably attending the École des Beaux-Arts, the bastion of traditional art education in France. Sources indicate he studied under figures like Jacques-Fernand Humbert and Eugène Vallet. While the Beaux-Arts emphasized classical principles and techniques, Paris itself was a crucible of modern art. Maillaud would have been exposed to the works of the Impressionists – Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas – who had already challenged academic conventions decades earlier.

His training likely provided him with a solid technical grounding, but his artistic spirit resonated more strongly with subsequent movements. The influence of Jean-François Millet, the Barbizon school painter renowned for his dignified portrayals of peasant life, is often noted in Maillaud's work. Millet's elevation of rural labor to a subject worthy of serious art undoubtedly struck a chord with Maillaud's own background and interests. Furthermore, the burgeoning Post-Impressionist and Symbolist movements, spearheaded by artists like Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, offered new ways to express subjective experience and deeper meanings beyond mere visual representation, directions Maillaud would explore in his mature work.

The Heart of France: Berry and Creuse

While Paris provided training and connections, the true heart of Fernand Maillaud's art lies in the French countryside, specifically the regions of Berry and Creuse. He developed a profound attachment to these areas, returning to them repeatedly throughout his life. The landscapes of the Creuse valley, with its rolling hills, winding rivers, and distinctive light, became a signature subject. This region had already attracted artists before him, forming part of what became known as the École de Crozant, which included painters like Armand Guillaumin, who captured the rugged beauty of the area with Impressionist techniques.

Maillaud's connection went beyond mere landscape painting. He immersed himself in the local life, observing the markets, the agricultural rhythms, and the enduring traditions of the Berrichon people. This deep engagement is reflected in the authenticity and empathy of his depictions. His commitment to the region was solidified by his decision to build a house and studio, "Le Renabec," in Guéret, the prefecture of the Creuse department. This became his sanctuary, a place where he could live and work in close proximity to his primary source of inspiration, particularly during the summer months. This focus on a specific region aligns him with other artists deeply connected to their native soil, such as Paul Cézanne in Provence.

Weaving Styles: Post-Impressionism and Symbolism

Fernand Maillaud's artistic style is often characterized as a blend of Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. He absorbed lessons from the Impressionists regarding light and color but moved beyond their focus on capturing fleeting moments. Like the Post-Impressionists, he used color more subjectively and expressively, emphasizing structure and emotional content. His brushwork could be vigorous, building forms with a tangible presence, yet always serving the overall mood of the scene. His landscapes often possess a solidity and permanence that contrasts with the ephemeral quality sought by Monet.

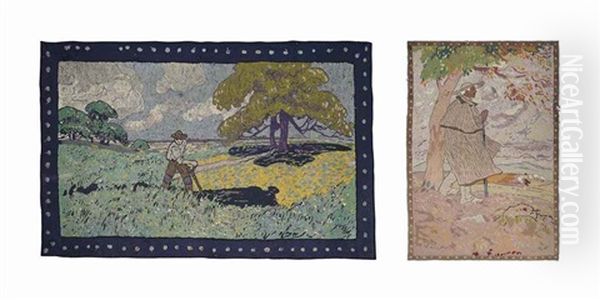

The influence of Symbolism is evident in the evocative atmosphere and suggestive qualities of many of his works. Rather than simply documenting rural life, Maillaud often imbued his scenes with a sense of timelessness, harmony, or quiet contemplation. He sought to convey the deeper spirit of the place and its people. While perhaps not as overtly mystical as Odilon Redon or Gustave Moreau, his work shares the Symbolist interest in conveying ideas and emotions indirectly through visual means. His association with Paul Gauguin's circle, even if informal, places him within this milieu that valued subjective experience and decorative arrangement over strict naturalism. Some sources also mention tapestry designs based on literary or legendary themes, such as Tristan et Iseult, which would directly align with Symbolist interests in myth and narrative.

Enduring Themes: Landscape, Labor, and Life

The thematic range of Maillaud's work is consistent yet rich. Landscapes form the bedrock of his oeuvre. He painted the Berry and Creuse countryside in all seasons, sensitive to the changing light and atmosphere. His canvases capture the golden glow of harvest time, the stark beauty of winter fields, and the vibrant greens of spring. These are not just topographical records; they are deeply felt responses to the spirit of the land, often conveying a sense of peace and enduring nature.

Market scenes are another recurring subject, allowing Maillaud to depict the social heart of rural communities. These paintings are often animated, filled with figures engaged in trade and conversation, capturing the local color and energy. His portrayal of peasants and agricultural labor is central to his work, echoing Millet but with his own distinct sensibility. He depicts farmers plowing, harvesting, or tending livestock with a sense of dignity and rhythm. Critics have noted that his portrayal often emphasizes social harmony and the seemingly unchanging cycles of rural existence, sometimes leading to charges of idealization, particularly when viewed against the backdrop of agricultural modernization and hardship.

Maillaud also traveled and painted beyond central France. He spent time in Provence, capturing the distinct light and landscapes of the south, and even worked in North Africa, particularly Algeria. These works add another dimension to his output, engaging with the different cultural contexts and visual stimuli of these regions, placing him within the broader tradition of French artists traveling to the Mediterranean and beyond, a path trod by artists from Eugène Delacroix to Henri Matisse. Portraiture also formed part of his practice, though it is perhaps less central than his landscapes and genre scenes.

Beyond the Canvas: Maillaud the Designer

A distinctive aspect of Fernand Maillaud's career is his significant activity in the decorative arts. He did not confine his creative energies solely to painting. In collaboration with his wife, Fernande Maillaud (née de Vasson, suggesting a connection to his friend, the photographer Jenny de Vasson), he designed and produced furniture and tapestries. This venture reflects a holistic approach to art-making, blurring the lines between fine art and craft, a philosophy shared by movements like the British Arts and Crafts led by William Morris, and aspects of Art Nouveau in France championed by figures like Émile Gallé.

Their designs often drew inspiration from regional styles and motifs, emphasizing craftsmanship and natural materials. The furniture might have featured robust forms and carved details reflecting Berrichon traditions, while the tapestries likely depicted scenes similar to his paintings – landscapes, rural life, perhaps even the aforementioned legendary themes. This work found considerable success, reportedly being popular not only in France but also exported to Great Britain and the United States. This parallel career highlights Maillaud's versatility and his commitment to integrating art into the fabric of everyday life, extending his aesthetic vision from the gallery wall into the domestic interior.

Recognition and Artistic Circles

Fernand Maillaud achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime. A key milestone was his regular participation in the prestigious Salon des Artistes Français in Paris. He made his debut there in 1896 and became a member (sociétaire) in 1901, indicating acceptance by the official art establishment. Participation in the Salon was crucial for visibility and sales. He likely exhibited in other venues as well, including the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts and various gallery exhibitions. His move to a Paris address around 1900 facilitated his engagement with the capital's art scene.

His reputation extended beyond France, evidenced by the international exhibitions of his work between 1910 and 1940, reaching audiences in Brazil, Argentina, and Algeria. This international exposure underscores his standing in the broader art world of the period. Within France, he maintained connections with fellow artists. His friendships with the photographer Jenny de Vasson, and writers like Jacques des Gachons and Hugues Laplace, suggest a cultured circle interested in the arts and regional identity. His brother, Joseph-Firmin Maillaud, was also a painter, indicating a familial artistic environment. While cooperative relationships existed, the art world was also competitive. Maillaud's style, focused on rural tranquility, differed significantly from the avant-garde experiments of Fauvism (Matisse, André Derain) or Cubism (Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque) that emerged during his mature career, placing him in a distinct, perhaps more conservative, though highly respected, niche.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Fernand Maillaud remained active as an artist for much of his long life. He continued to divide his time between his various bases: his Paris residence, his beloved "Le Renabec" in Guéret for summer work, and potentially "La Florenta," a villa he reportedly built in Toulon on the Mediterranean coast, suggesting a continued draw to the light and landscapes of the south. He witnessed profound historical upheavals, including two World Wars, yet his art largely remained focused on the enduring themes of nature and rural life, perhaps offering a vision of stability and continuity in turbulent times.

He passed away in Paris in 1948, leaving behind a substantial body of work across painting and decorative arts. His legacy is that of a dedicated and sensitive chronicler of French provincial life, particularly the Berry and Creuse regions he knew so intimately. He occupies a unique position, bridging the observational traditions of the 19th century with the subjective and symbolic concerns of early 20th-century modernism. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, his work possesses a quiet strength, technical skill, and deep sincerity. The preservation of his studio, "Le Renabec," serves as a tangible link to his life and creative process. Fernand Maillaud remains an important figure for understanding French regionalist painting and the diverse artistic currents that flowed between Impressionism and the more radical movements of the twentieth century. His paintings continue to be appreciated for their evocative beauty and their heartfelt tribute to the landscapes and people of rural France.