Jules Adolphe Aimé Louis Breton stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century French art, celebrated primarily for his sensitive and often idealized depictions of rural peasant life. Bridging the gap between academic tradition and the burgeoning Realist movement, Breton carved a unique niche for himself, achieving immense popularity both in France and internationally during his lifetime. His canvases, imbued with a distinct poetic quality and a profound respect for the dignity of labor, captured the rhythms, hardships, and simple beauties of the French countryside, particularly his native region of Artois. As both a painter and a published poet, Breton offered a romanticized yet deeply felt vision of agrarian existence that resonated strongly with contemporary audiences.

Early Life and Formative Influences in Artois

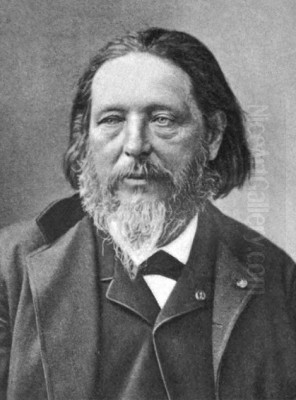

Jules Breton was born on May 1, 1827, in Courrières, a small village in the Pas-de-Calais department of the Artois region in northern France. This area, characterized by its flat, expansive fields and close-knit agricultural communities, would remain the primary source of inspiration throughout his artistic career. His father, Marie-Louis Breton, managed the estate of a wealthy landowner, providing young Jules with a comfortable upbringing, albeit one deeply immersed in the realities of rural life.

A significant personal tragedy marked Breton's early childhood: the death of his mother when he was just four years old. He was subsequently raised by his father, his maternal grandmother, and an uncle, Félix De Vigne, who was himself a painter. This early loss and the strong familial bonds forged in its wake likely contributed to the artist's later sensitivity and perhaps his tendency to portray female figures with particular grace and resilience. His upbringing instilled in him a deep familiarity with and affection for the landscapes and people of Artois.

His uncle, Félix De Vigne, recognized Jules's artistic talent early on and encouraged his pursuits. It was through De Vigne that Breton received his initial artistic guidance. This familial connection provided a supportive environment for the young artist to develop his skills before seeking more formal training elsewhere. The sights and sounds of Courrières – the fields, the harvests, the local customs, and the stoic figures of the peasants – became ingrained in his consciousness, forming the bedrock of his future artistic vision.

Artistic Education: Ghent, Antwerp, and Paris

Following the encouragement of his family, particularly his uncle Félix De Vigne, Breton embarked on a formal artistic education. In 1843, he traveled to Ghent, Belgium, to study at the Academy of Fine Arts. There, he entered the studio of De Vigne himself, further solidifying his foundational skills. He later continued his studies in Antwerp under the tutelage of Baron Gustaaf Wappers, a prominent Belgian painter known for his historical and romantic subjects. This period exposed Breton to the Flemish tradition, with its rich color and attention to detail.

In 1847, Breton moved to Paris, the epicenter of the European art world. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he briefly studied with Michel Martin Drolling. Paris offered a wealth of artistic stimulation, exposing him to the masterpieces housed in the Louvre and the vibrant contemporary art scene. He encountered the works of past masters, including the Italian Renaissance giants like Michelangelo and Raphael, whose sense of form and idealized beauty left an impression on his developing style.

During his time in Paris, Breton also associated with other artists who were exploring new directions in art. He became acquainted with figures connected to the Realist movement, such as François Bonvin and Gustave Brion. While initially drawn to historical subjects, influenced by his academic training and teachers like Wappers, the political and social climate of Paris, particularly the Revolution of 1848, began to steer his interests towards contemporary life and the depiction of ordinary people.

The Turn Towards Rural Realism

Breton's early career saw him attempting historical paintings, aligning with the academic expectations of the time. However, a pivotal shift occurred in the early 1850s. Disillusionment with purely historical themes, combined with the social consciousness stirred by the 1848 Revolution and a deep-seated connection to his roots, led him back to the subjects he knew best: the peasants and landscapes of Artois.

A key influence in this transition was the work of the Swiss painter Léopold Robert. Breton was particularly struck by Robert's depictions of Italian peasant life, such as his famous Harvesters Arriving in the Pontine Marshes. Robert's ability to imbue scenes of rural labor with a sense of classical dignity and picturesque charm resonated with Breton's own inclinations. This encounter helped solidify his decision to focus on the agrarian world he had grown up in.

His painting Return of the Reapers (1853), exhibited at the Paris Salon, marked a significant step in this new direction. Although still displaying some academic polish, its subject matter firmly established his commitment to rural themes. This work garnered positive attention and signaled the emergence of a distinct artistic voice. From this point forward, Breton dedicated himself almost exclusively to capturing the life and labor of the French countryside, finding in it a source of enduring artistic and emotional significance.

Breton's Mature Style: Idealized Realism

Jules Breton developed a style that blended meticulous observation, characteristic of Realism, with a distinct sense of poetry and idealization. Unlike the often stark and critical portrayals of peasant life found in the works of contemporaries like Gustave Courbet or Jean-François Millet, Breton's vision was generally more harmonious and serene. He depicted the hardships of rural labor but often softened the edges, emphasizing the dignity, resilience, and quiet beauty of his subjects.

His compositions are typically well-structured, often drawing on classical principles of balance and harmony learned during his academic training. Figures are rendered with care and precision, demonstrating strong draftsmanship. Breton possessed a remarkable sensitivity to light and atmosphere, frequently setting his scenes at dawn or dusk. The warm, golden light of late afternoon or the soft glow of twilight often bathes his landscapes, lending them a tranquil, almost elegiac quality. This use of light contributes significantly to the poetic mood that permeates much of his work.

Breton excelled at portraying single female figures, often depicted pausing during their work in the fields. These women possess a statuesque grace, sometimes appearing almost monumental against the backdrop of the landscape. While grounded in reality, they often transcend mere documentation, embodying timeless virtues of strength, piety, and connection to the earth. This idealization, while sometimes criticized by later modernists for lacking gritty realism, was precisely what appealed to many collectors and the public during his time, offering a comforting and ennobling vision of rural life amidst rapid industrialization.

Masterpieces of Rural Life

Throughout his long career, Jules Breton produced numerous paintings that became icons of nineteenth-century rural genre painting. Among his most celebrated works is The Gleaners (Les Glaneuses), a theme he revisited multiple times. While Jean-François Millet's 1857 painting of the same name is perhaps more famous today for its stark portrayal of poverty, Breton's versions often present the gleaners with a greater sense of individual grace and quiet endurance, set within beautifully rendered landscapes. His The Last Gleaners (1895) continues this exploration late in his career.

The Song of the Lark (Le Chant de l'Alouette), painted in 1884, is arguably Breton's most famous work, particularly in the United States where it resides in the Art Institute of Chicago. It depicts a young peasant woman, sickle in hand, pausing in the field at dawn, captivated by the song of a lark. Her silhouette against the rising sun, her bare feet planted firmly on the earth, and her upward gaze combine realism with profound poetic feeling. The painting became immensely popular, symbolizing the connection between humanity, nature, and a simple, spiritual awakening.

Other significant works include Blessing the Wheat in Artois (1857), a large canvas depicting a religious procession through the fields, showcasing his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and capture communal traditions. The Recall of the Gleaners (1859) earned him a first-class medal at the Salon and cemented his reputation. Evening (1860) and The Weeders (1861) further exemplify his skill in capturing atmospheric effects and the quiet rhythms of agricultural tasks. Fin du travail (End of the Working Day) encapsulates his recurring theme of laborers concluding their toil under the evocative light of dusk.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Connections

Jules Breton's artistic journey was shaped by various influences and situated within a rich network of contemporary artists. His early training under Félix De Vigne and Gustaaf Wappers provided a solid academic foundation rooted in Belgian traditions. The influence of Italian Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo is discernible in the classical structure and idealized forms found in some of his figures. The aforementioned Léopold Robert played a crucial role in directing him towards peasant themes.

Breton was a contemporary of the major figures of French Realism and the Barbizon School. He undoubtedly knew the work of Jean-François Millet, who also specialized in peasant subjects. While both artists shared a common focus, their approaches differed: Millet's work often carried a heavier, more somber tone, emphasizing the burden of labor, whereas Breton's interpretations tended towards the lyrical and picturesque. He also operated in the same era as Gustave Courbet, the leading proponent of Realism, though Breton's style remained more polished and less confrontational than Courbet's.

He maintained connections with other artists focused on rural or natural scenes, such as the painters of the Barbizon School like Constant Troyon, known for his landscapes and animal paintings, and the highly successful animal painter Rosa Bonheur. His work, with its blend of realism and sentiment, also found parallels in the paintings of artists like Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, who followed Breton in depicting rural scenes with photographic precision and emotional depth later in the century.

Breton's success placed him in a different sphere from the emerging Impressionists like Claude Monet or Edgar Degas, whose focus on capturing fleeting moments and sensations, and their looser brushwork, represented a radical departure from Breton's more finished style. Yet, his fame was such that even artists of the next generation were aware of him. Vincent van Gogh famously admired Breton's work, particularly his depictions of peasants and his perceived sincerity. Van Gogh undertook a long journey on foot in 1880 with the intention of meeting Breton, though ultimately, intimidated by the apparent affluence of Breton's studio, he turned back without introducing himself. This incident highlights the stature Breton held, even for artists forging vastly different paths. His work stood in contrast to the highly polished academic nudes and historical scenes of contemporaries like William-Adolphe Bouguereau or Jean-Léon Gérôme, offering a popular alternative focused on contemporary rural life.

The Poet and Writer

Beyond his achievements as a painter, Jules Breton was also a recognized poet and writer. His literary pursuits were not separate from his art but rather complemented and enriched his visual work. He published several volumes of poetry, beginning with Les Champs et la mer (Fields and Sea) in 1875, followed by Jeanne (1880), a narrative poem. His poetry often explored the same themes found in his paintings: the beauty of nature, the life of peasants, the changing seasons, and reflections on art and existence.

Breton also penned autobiographical writings that provide valuable insights into his life, artistic philosophy, and the art world of his time. La Vie d'un artiste: Art et nature (The Life of an Artist: Art and Nature, 1890) and Un Peintre paysan (A Peasant Painter, 1895) recount his experiences, his artistic development, and his thoughts on fellow artists. He also wrote Nos peintres du siècle (Our Painters of the Century, 1900), offering his perspective on contemporary art.

His writing reveals a thoughtful and articulate individual, deeply committed to his chosen themes. It underscores the poetic sensibility that infused his paintings, demonstrating that his romanticized view of rural life stemmed from genuine affection and contemplation rather than mere commercial calculation. His dual identity as painter and poet reinforces the lyrical quality that distinguishes his work from that of more objective or socially critical Realists.

Reception, Fame, and Reputation

During his lifetime, Jules Breton achieved remarkable success and international acclaim. He was a regular and celebrated exhibitor at the Paris Salon, winning numerous medals and honors, including the prestigious Medal of Honor in 1872. He was elected a member of the Institut de France in 1886, a significant recognition of his status within the French cultural establishment. The French state acquired several of his works for national museums, including the Musée du Luxembourg (the precursor to the Musée d'Orsay for contemporary art).

His paintings were highly sought after by collectors, not only in France but also, significantly, in the United Kingdom and the United States. American collectors, in particular, developed a strong appetite for his work, drawn to its perceived sincerity, technical polish, and reassuringly positive portrayal of rural values. Works like The Song of the Lark became beloved images in American culture. This international demand contributed to his financial success and widespread fame.

However, with the rise of Impressionism and subsequent modernist movements towards the end of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, Breton's reputation began to decline among avant-garde critics. His work came to be seen by some as overly sentimental, academic, and lacking the innovative spirit of modern art. His polished technique and idealized subjects seemed out of step with the new emphasis on subjective experience, formal experimentation, and sometimes harsher social realities. For much of the twentieth century, he was somewhat overlooked or dismissed as a relic of conservative nineteenth-century taste.

Later Life and Re-evaluation

Jules Breton continued to paint and write into his later years, remaining largely faithful to the themes and style that had brought him success. He divided his time between Paris and his beloved Courrières, constantly returning to the source of his inspiration. He remained a respected figure, even as artistic tastes shifted around him. His dedication to his craft and his chosen subject matter never wavered.

He passed away in Paris on July 5, 1906, at the age of 79. He was buried in Montparnasse Cemetery. While his critical standing experienced a decline in the decades following his death, recent art historical scholarship has led to a re-evaluation of his work. Art historians now recognize his technical skill, his importance within the context of nineteenth-century Realism and Naturalism, and the genuine poetic feeling that animates his best paintings.

His work is acknowledged for its role in popularizing rural themes and for offering a particular vision of peasant life that, while idealized, resonated deeply with the anxieties and aspirations of his era. Museums continue to display his paintings, and works like The Song of the Lark retain their power to captivate audiences. He is understood today not just as a painter of peasants, but as an artist who skillfully blended observation, tradition, and personal sentiment to create a unique and enduring body of work.

Legacy of the Poet-Painter

Jules Breton's legacy lies in his distinctive contribution to nineteenth-century French art as a "poet-painter" of rural life. He successfully navigated the space between academic tradition and Realism, creating works that were both technically accomplished and emotionally resonant. His idealized yet deeply felt depictions of peasants and landscapes offered a vision of dignity, harmony, and connection to nature that found widespread appeal in an age of increasing industrialization and social change.

While perhaps overshadowed for a time by the more radical innovations of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Breton's art endures. His paintings provide a valuable window into the agrarian world of nineteenth-century France and reflect the complex attitudes towards rural life held during that period. His ability to infuse scenes of everyday labor with poetic light and quiet monumentality remains compelling. Through his dual talents as a painter and writer, Jules Breton crafted a unique and lasting tribute to the enduring rhythms of the French countryside and the people who worked its soil.