Francesco Montelatici, more famously known by his evocative nickname Cecco Bravo (1601–1661), stands as one of the most intriguing and individualistic painters of the Florentine Seicento. Active primarily in his native Florence before a brief concluding period in Innsbruck, Austria, Cecco Bravo forged a distinctive artistic path. His style, characterized by a fluid brushwork, often melancholic or dreamlike atmospheres, and a complex synthesis of diverse influences, set him apart from many of his contemporaries. While he absorbed lessons from his teachers and admired masters of the High Renaissance and the burgeoning Baroque, his output was uniquely his own, often defying easy categorization and leading to a period of relative obscurity before his significant reassessment by modern art historians.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Florence

Born in Florence in 1601, Francesco Montelatici entered a city rich with artistic heritage but also one seeking new directions after the High Renaissance and the complexities of Mannerism. The artistic environment was vibrant, with workshops bustling and patrons, both ecclesiastical and private, commissioning a wide array of works. It was in this milieu that the young Montelatici began his artistic training.

His primary master was Giovanni Bilivert (1585–1644), a prominent Florentine painter who himself had trained under Cigoli (Ludovico Cardi). Bilivert's style was a sophisticated blend of late Florentine Mannerism's elegance with the newer, more naturalistic and dramatic impulses stemming from Caravaggio, albeit often softened and refined. From Bilivert, Cecco Bravo would have learned the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and the handling of paint, likely absorbing an appreciation for rich color and expressive figural representation. Bilivert's workshop was a significant training ground, and his influence can be discerned in the careful construction and emotional tenor of some of Bravo's earlier works.

Beyond Bilivert, Cecco Bravo also had significant interactions with, and likely worked alongside, Matteo Rosselli (1578–1650). Rosselli was one of the leading figures in Florentine painting in the first half of the 17th century, heading a large and productive workshop that trained many artists, including Lorenzo Lippi and Baldassare Franceschini (Il Volterrano). Rosselli's style was generally more classical and academic than Bilivert's, emphasizing clarity, balanced compositions, and a certain decorum. Collaboration with Rosselli, or time spent in his circle, would have exposed Cecco Bravo to a different artistic approach, one grounded in the Florentine tradition of disegno (design and drawing) but also open to contemporary developments. This period was crucial for Montelatici, allowing him to hone his skills and begin to assimilate the varied artistic currents present in Florence.

The Development of a Personal Idiom: Influences and Early Works

As Cecco Bravo matured, his artistic voice began to distinguish itself more clearly. While rooted in his Florentine training, he demonstrated a keen interest in a wide range of other artistic sources, which he masterfully synthesized into a highly personal style. Among the High Renaissance masters, he particularly admired Antonio Allegri da Correggio (c. 1489–1534) and Francesco Mazzola, known as Parmigianino (1503–1540). From Correggio, he likely drew inspiration for the soft, sfumato-laden modeling of figures and the gentle, often sensuous, grace of his characters. Parmigianino's elegant, elongated figures and sophisticated, sometimes enigmatic, compositions also seem to have resonated with Bravo's developing aesthetic.

The influence of Venetian painting, particularly its emphasis on colorito (color) and expressive brushwork, was also significant. Artists like Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese had established a tradition of rich chromatic effects and dynamic compositions that offered an alternative to the more drawing-focused Florentine school. Cecco Bravo's handling of paint, which became increasingly free and painterly, suggests an absorption of these Venetian qualities, perhaps encountered through visits, prints, or works in Florentine collections.

Furthermore, the dramatic naturalism and potent chiaroscuro of Caravaggio (1571–1610) and his followers, the Caravaggisti, left an indelible mark on European painting, and Florence was no exception. While Cecco Bravo was not a direct follower of Caravaggio in the way artists like Artemisia Gentileschi or Bartolomeo Manfredi were, the heightened sense of drama, the use of strong light and shadow contrasts, and the psychological intensity found in some of his works reflect an awareness of this powerful artistic current. Similarly, the dynamism and vibrant energy of Flemish Baroque painters, notably Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640), whose works were known internationally, may have contributed to the animated quality of Bravo's compositions.

His early works began to showcase this emerging synthesis. Around 1628-29, he painted frescoes in the Chiostro dei Morti at the church of San Marco in Florence, depicting scenes with the Virgin, St. John, and angels. He also created a painting of "Charity" for the church of Santissima Annunziata. These commissions indicate his growing reputation and his ability to tackle significant public projects. In these early endeavors, one can see the Florentine grounding in drawing and composition, but also a burgeoning interest in more expressive and less conventional approaches to form and color.

Mature Style and Key Florentine Commissions

By the 1630s, Cecco Bravo had established himself as a notable, if somewhat unconventional, figure in the Florentine art scene. He became a studio head and undertook several important commissions. One significant project was the series of frescoes depicting scenes from the life of St. Bonaventure, painted around 1633 for the Cappella Lenzi in the church of San Salvatore in Ognissanti (sometimes referred to as San Vicenzo d'Annalena in some older sources, but Ognissanti is the more established location for these works). These frescoes would have allowed him to demonstrate his narrative skills and his increasingly fluid and expressive style on a larger scale.

Perhaps one of his most celebrated surviving fresco cycles is in the Sala degli Argenti (Silver Room) of the Palazzo Pitti, though the provided text attributes "Lorenzo Welcomes the Muses and Virtues" to the church of San Lorenzo. It's important to note that Cecco Bravo did contribute significantly to the Sala degli Argenti, working alongside other artists like Giovanni da San Giovanni and Francesco Furini under the direction of the Grand Ducal court. His contributions there, such as "Lorenzo the Magnificent as Patron of the Arts," showcase his mature style, blending an almost ethereal quality with dynamic movement. If the San Lorenzo fresco of "Lorenzo Welcomes the Muses and Virtues" is a distinct work, it would similarly reflect this period's characteristics: a Renaissance-inspired elegance infused with Baroque dynamism and a deeply personal, almost melancholic sensibility. His figures often possess a languid grace, their forms sometimes dissolving into the surrounding atmosphere through his characteristic soft brushwork.

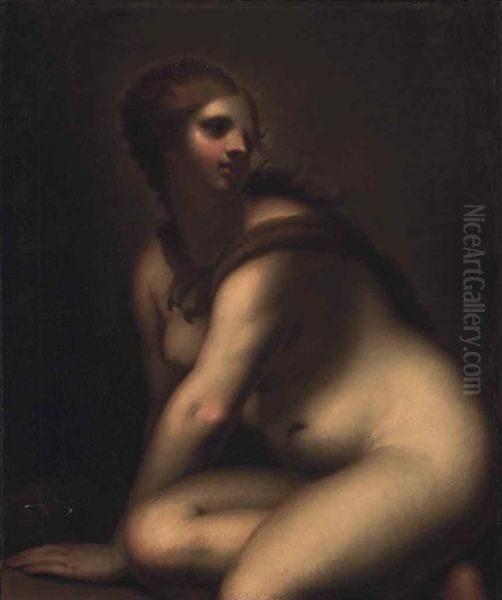

Cecco Bravo's easel paintings from this period further explore his unique vision. Subjects ranged from religious scenes and mythological narratives to allegorical figures. His technique became increasingly characterized by rapid, visible brushstrokes, creating a flickering, almost impressionistic effect, particularly in his treatment of drapery and landscapes. This "pittura di tocco" (painting of touch) or "macchia" (stain, spot) approach was quite distinct from the polished finish favored by many of his Florentine contemporaries, such as the meticulously detailed works of Carlo Dolci. Bravo's colors are often muted, with subtle harmonies, but can also feature unexpected flashes of brighter hues that animate the composition.

A notable example of his later easel work is "The Temptation of Eve," now housed in the Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya in Barcelona. This painting exemplifies his mature style: the figures are rendered with a characteristic softness, almost dematerializing at the edges, and the landscape is evoked with a remarkable freedom and atmospheric sensitivity. The overall mood is one of dreamlike introspection, a hallmark of much of his oeuvre. Another work sometimes mentioned, "Ulysses and Nausicaa," highlights the challenges in studying his work, as it, like many paintings of its era, has undergone restorations that may have altered its original appearance.

The Innsbruck Period and Final Years

Towards the end of his life, Cecco Bravo's reputation extended beyond Tuscany. Around 1659 or 1660 (sources vary slightly, with 1660 being more commonly cited for his arrival), he accepted an invitation to work at the court of Archduke Ferdinand Charles in Innsbruck, Austria. Archduke Ferdinand Charles (1628–1662) was the ruler of Further Austria and Tyrol, and his mother was Claudia de' Medici, linking him to the Florentine artistic sphere. This connection likely facilitated Bravo's appointment.

The move to Innsbruck represented a significant change for the artist, taking him away from his native Florence, where he had spent virtually his entire career. At the Habsburg court in Innsbruck, he would have been expected to produce works befitting a princely patron, likely including portraits, allegorical paintings, and possibly decorative schemes. Unfortunately, his time in Innsbruck was brief. Cecco Bravo died there in 1661, only a year or two after his arrival. Consequently, the body of work definitively attributed to his Innsbruck period is not extensive, and further research continues to illuminate this final phase of his career. His death in Innsbruck marked the end of a unique artistic journey, far from the familiar artistic environment of Florence.

Cecco Bravo's Distinctive Artistic Language: Technique and Expression

Cecco Bravo's art is most remarkable for its highly individualistic style, which, while drawing from diverse sources, remained uniquely his own. His technique was central to this distinctiveness. He employed a notably free and often rapid brushwork, creating a sense of immediacy and vibrancy. This approach, sometimes described as "sfumato-like" or almost "impressionistic" in its looseness, allowed forms to emerge softly from the background, imbuing his figures with an ethereal, almost ghostly quality. This contrasted sharply with the precise linearity and polished surfaces favored by more classical Florentine painters.

His use of chiaroscuro was subtle yet effective, often creating a soft, diffused light rather than the stark, dramatic contrasts of the more overt Caravaggisti. This contributed to the often melancholic, dreamlike, or intensely private mood of his paintings. His figures, frequently elegant and elongated, convey a sense of introspection or languor. Even in more dynamic compositions, there is often an underlying current of poetic reverie.

Color in Cecco Bravo's work is also distinctive. He often favored a palette of muted tones – ochres, browns, grays, and subtle greens – which enhanced the atmospheric quality of his scenes. However, he could also employ surprising accents of richer color, such as deep reds or blues, to draw attention to specific elements or to heighten the emotional impact.

His drawings, many of which survive, are crucial for understanding his creative process. Executed with a similar freedom and expressiveness as his paintings, often in red or black chalk, they reveal his initial thoughts, his exploration of form and composition, and his mastery of capturing movement and emotion with a few swift strokes. These drawings underscore his departure from purely academic methods and highlight his more intuitive and personal approach to art-making. Artists like Sigismondo Coccapani, another Florentine contemporary who sometimes shared a certain eccentricity in style, might offer a point of comparison, though Bravo's path was ultimately his own.

Legacy, Misattributions, and Scholarly Reassessment

For a considerable time after his death, Cecco Bravo's work fell into relative obscurity. His highly personal and often unconventional style did not align easily with the prevailing classical tastes that dominated much of the later Baroque and Neoclassical periods. Furthermore, the very individuality that makes his work so compelling today perhaps made it difficult to categorize and appreciate in an era that often valued adherence to established artistic norms.

This led to some of his paintings being misattributed to other artists. For instance, works with a soft, sfumato quality might have been ascribed to Francesco Furini (c. 1603–1646), a Florentine contemporary known for his sensuous and hazy depictions of mythological and biblical subjects. The painting "K1371," mentioned in the provided information, was initially thought to be by Furini before being correctly reattributed to Cecco Bravo, highlighting the stylistic overlaps that could cause confusion. Other works might have been attributed to artists like Sebastiano Mazzoni, a Florentine who worked mainly in Venice and also possessed a rather eccentric and painterly style.

The modern "rediscovery" and reassessment of Cecco Bravo owe much to 20th-century art historical scholarship. Scholars, notably Gerhard Ewald, undertook pioneering research to reconstruct Bravo's oeuvre, distinguish his hand from those of his contemporaries, and articulate the unique qualities of his art. This scholarly attention has brought Cecco Bravo out of the shadows, revealing him as one of the most original and imaginative painters of the Florentine Seicento. His work is now appreciated for its poetic sensitivity, its technical freedom, and its deeply personal vision. He is recognized for his ability to create hauntingly beautiful images that resonate with a quiet emotional intensity. His frescoes, such as the "St. Michael Defeating the Rebel Angels" (which was reportedly partially damaged or destroyed), further attest to his capabilities in large-scale decorative work, even if their survival is precarious.

A Necessary Clarification: Distinguishing from Giovanni Montelatici

It is crucial to distinguish Francesco "Cecco Bravo" Montelatici (1601–1661), the Baroque painter, from another artist named Giovanni Montelatici (1864–1930). This later Montelatici was active in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and was renowned for his work in pietra dura (hardstone mosaic). Giovanni Montelatici played a significant role in reviving this traditional Florentine craft, gaining international acclaim for his intricate and artistic pietra dura pieces, such as a notable tabletop exhibited at the Paris Exposition of 1900. He collaborated with artists like Galileo Chini on large mosaic works. While both artists share a surname and a Florentine origin, their artistic periods, mediums, and styles are entirely distinct. The information provided in the initial query occasionally conflated these two figures, so this clarification is essential for an accurate understanding of Cecco Bravo, the 17th-century painter.

Conclusion: Cecco Bravo's Enduring Place in Art History

Francesco "Cecco Bravo" Montelatici remains a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of 17th-century Italian art. He was an artist who, while trained within the Florentine tradition and responsive to a wide array of influences – from Correggio and Parmigianino to Venetian colorism and Caravaggesque drama – ultimately forged a path that was uniquely his own. His distinctive brushwork, his evocative and often melancholic atmospheres, and his highly personal interpretations of religious and mythological themes set him apart from the more mainstream currents of his time.

Though perhaps not as widely known as some of his more classical contemporaries like Cesare Dandini or Felice Ficherelli, Cecco Bravo's art offers a compelling glimpse into the diversity and imaginative richness of Florentine Seicento painting. His rediscovery by modern scholarship has rightfully secured him a place as a significant and highly individualistic master, whose works continue to intrigue and captivate with their poetic beauty and expressive depth. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of a singular artistic vision within the broader currents of art history.