Francesco Solimena stands as a towering figure in the landscape of Italian art history, particularly renowned for his prolific output and profound influence during the late Baroque period. His career, spanning nearly seven decades, saw him become the undisputed leader of the Neapolitan School of painting, shaping its direction and leaving an indelible mark on European art. His life and work represent a fascinating blend of artistic inheritance, innovation, and pedagogical impact.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Francesco Solimena was born on October 4, 1657, in Canale di Serino, located in the province of Avellino, near Naples. His artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, Angelo Solimena, who was himself a painter of note. This early training within the family workshop provided Francesco with a solid foundation in the techniques and traditions of painting prevalent in the region.

A significant early collaboration between father and son was the fresco depicting Paradise, created for the dome of Nocera Cathedral. Working alongside Angelo, the young Francesco gained invaluable practical experience in large-scale mural painting, a medium in which he would later excel. This project demonstrated his burgeoning talent and set the stage for his future artistic endeavors. The guidance received from his father was crucial in honing his skills and instilling a deep understanding of the painter's craft from a young age.

Emergence in Naples and Key Influences

Recognizing the greater opportunities available in the vibrant artistic center of Naples, Solimena relocated there to further develop his career. The city was a crucible of artistic activity, and Solimena quickly absorbed the prevailing influences while forging his own distinct path. He arrived at a time when the Neapolitan art scene was still resonating with the impact of earlier masters.

Solimena's artistic development was significantly shaped by exposure to the works of several prominent Baroque painters. He deeply admired the dynamic energy and compositional brilliance of Luca Giordano, whose speed of execution and dramatic flair were legendary in Naples. The powerful chiaroscuro and tenebrism associated with Mattia Preti, another major figure active in Naples after spending time in Malta, also left a discernible mark on Solimena's handling of light and shadow.

Furthermore, the influence of Roman Baroque masters like Luigi Lanfranco, known for his illusionistic ceiling frescoes and dramatic compositions, can be detected in Solimena's approach to large-scale decorative schemes. The grandeur and formal structure found in the works of Pietro da Cortona, a leading figure of the High Baroque in Rome, also informed Solimena's evolving style, particularly his tendency towards complex, multi-figured scenes imbued with a sense of theatricality. These influences synthesized within Solimena's work, creating a style that was both rooted in tradition and uniquely his own.

Defining the Solimena Style: Light, Drama, and Classicism

Francesco Solimena's mature style is characterized by its dramatic intensity, sophisticated use of light and shadow, and complex, often crowded compositions. He became a master of chiaroscuro, employing strong contrasts between light and dark not merely for realistic modeling, but to heighten the emotional impact and visual drama of his scenes. This technique, ultimately derived from the innovations of Caravaggio earlier in the 17th century, was adapted by Solimena to suit the grander, more decorative aims of the late Baroque.

His works often feature swirling movement, elaborate architectural settings, and figures depicted in dynamic, expressive poses. While deeply embedded in the Baroque tradition, Solimena's art also demonstrates a gradual inclination towards greater clarity and formal balance, sometimes described as a leaning towards classicism, particularly in his later career. This involved a more controlled composition and a refinement of form, moving slightly away from the raw energy of his predecessors like Giordano.

Solimena possessed a remarkable versatility, adeptly handling various subjects. Religious themes formed a significant part of his output, including numerous altarpieces and frescoes for churches throughout Naples and beyond. He also excelled in mythological narratives, allegorical paintings, and portraiture, capturing the likenesses of prominent figures of his time. His palette, often rich and vibrant, shows an awareness of Venetian colorism, adding another layer to his complex stylistic synthesis.

Masterpieces and Major Themes

Throughout his long and productive career, Francesco Solimena created a vast body of work. Several key pieces exemplify his style and thematic concerns. The painting Armida e Rinaldo (Armida and Rinaldo), though described as unfinished in some accounts, tackles a popular theme from Torquato Tasso's epic poem Gerusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered). It showcases Solimena's ability to translate literary narratives into compelling visual form, focusing on the emotional transformation of the characters, using concise and effective symbolism.

His numerous depictions of the Madonna and Child, including related subjects like the Annunciation, highlight his mastery of religious iconography. These works often combine tender sentiment with the characteristic Baroque dynamism and sophisticated handling of light, drapery, and figure placement. A specific Annunciation (titled Die Verkundigung in a German reference), dated 1733 and housed in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen, Denmark, is noted for its potent emotional expression and dramatic light effects, typical of his mature style.

Solimena undertook major commissions for ecclesiastical settings. His work for Neapolitan churches was extensive. For instance, the altarpiece depicting the Madonna and Saints created for a major Neapolitan church (potentially San Paolo Maggiore, though sometimes referred to as St. Peter's in sources) demonstrates his skill in creating large-scale devotional images that blend Baroque grandeur with a sense of classical order. These monumental works solidified his reputation as the leading religious painter in the city.

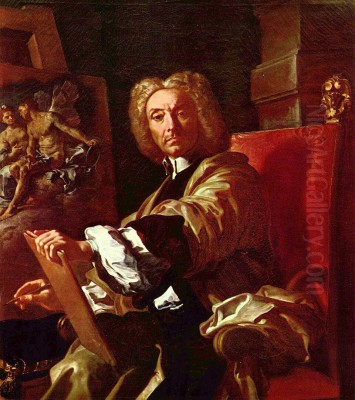

Allegory was another genre Solimena explored, as seen in the series known as the Allegory of Rule or Ragù, depicting the four continents (Europe, Africa, and Asia are specifically mentioned in sources). Housed in the Doria Pamphilj Gallery in Rome, this series allowed Solimena to engage with complex symbolic programs, showcasing his erudition and compositional inventiveness on a grand scale. Another notable work, Disputa di Gesù al Tempio (Jesus Disputing with the Doctors in the Temple), held in a private collection, further illustrates his command of complex, multi-figure compositions and dynamic narrative portrayal. His legacy also includes a self-portrait, offering insight into his appearance and artistic persona in his later years.

The Solimena Workshop: A Crucible of Talent

Beyond his personal artistic achievements, Francesco Solimena played a crucial role as a teacher. His studio in Naples became one of the most important artistic training centers in Europe during the first half of the 18th century. It functioned almost as an academy, attracting aspiring artists not only from Naples and other parts of Italy but also from across the continent. Solimena's dominance over the Neapolitan art scene was reinforced by the sheer number of artists who passed through his workshop.

He nurtured a generation of painters who would carry forward aspects of his style while developing their own artistic identities. Among his most celebrated pupils were Francesco De Mura and Giuseppe Bonito, both of whom became leading painters in Naples in the generation following Solimena. Corrado Giaquinto, another prominent student, achieved international success, working extensively in Rome and Madrid. Sebastiano Conca, trained by Solimena, also established a highly successful career, primarily in Rome.

The list of artists associated with his studio is extensive, reflecting its significance. Names mentioned include Giovanni De Marco, Giovanni Battista Pisano (or possibly Pittoni), Giovanni Torre, Pietro Capelli, Onofrio Avellino, Domenico Mondo, Valerio Polverino, Giuseppe Giovanni della Camera, Francesco Campanella, Leonardo Oliari, Olivieri Salerno, and Olivieri Pessi. Nicola Maria Rossi and Domenico Antonio Vaccaro, the latter also a noted sculptor and architect, were further figures connected to his circle. Even artists from abroad, such as the Scottish portraitist Allan Ramsay, sought instruction or inspiration from Solimena during their time in Italy. The workshop was a vital hub for the dissemination of late Baroque and emerging Rococo aesthetics.

European Renown and Prestigious Patronage

Francesco Solimena's fame was not confined to Naples or even Italy. His reputation spread throughout Europe, and his works were highly sought after by prestigious patrons, including royalty and aristocracy. King Louis XIV of France was among the notable collectors of his paintings, indicating his appeal at the highest levels of European society. Spanish nobles and members of other European royal courts also commissioned or acquired works by Solimena.

His close relationship with the church further enhanced his standing. He was reportedly acquainted with Cardinal Vincenzo Maria Orsini before he became Pope Benedict XIII and served as his spiritual advisor. This connection undoubtedly facilitated important ecclesiastical commissions and cemented his status within both religious and artistic circles. The demand for his paintings led to their dispersal across the continent, contributing to the spread of the Neapolitan late Baroque style. His influence extended to regions like Austria and Southern Germany, where his dramatic compositions and vibrant color schemes found resonance.

Architectural Endeavors

While primarily celebrated as a painter, Francesco Solimena also made contributions to architecture. He occasionally designed architectural elements and even entire structures, primarily churches and palaces within Naples. These architectural works, though less numerous than his paintings, reflected the same Baroque sensibility, characterized by dynamic forms, rich ornamentation, and a concern for dramatic spatial effects. His involvement in architecture demonstrates the breadth of his artistic talents and his engagement with the broader artistic culture of his time, where the lines between different artistic disciplines were often fluid.

Solimena in Context: Comparisons and Contrasts

Placing Solimena within the broader context of his time involves comparing his work to that of other major artists. While influenced by the dramatic realism and potent chiaroscuro pioneered by Caravaggio decades earlier, Solimena's style represents a later, more decorative evolution of the Baroque. Unlike Caravaggio's often gritty naturalism, Solimena's figures tend towards idealization, and his compositions possess a grandeur and complexity suited to aristocratic and ecclesiastical patrons. The intense light and shadow remain, but often serve a more theatrical purpose.

Comparing Solimena to his slightly later contemporary, the French Rococo master François Boucher (1703-1770), highlights the stylistic shifts occurring in the 18th century. Boucher's art epitomizes the lighthearted elegance, pastel colors, and sensual themes characteristic of the Rococo style favored by the court of Louis XV. While Solimena's later works show some Rococo influence in their refinement and lighter touches, his core style remained rooted in the more robust drama and gravitas of the Italian Baroque. Solimena represents the culmination of the Baroque tradition in Naples, while Boucher exemplifies the subsequent Rococo movement centered in France. Solimena's work retained a powerful emotional depth and compositional weight often absent in the more purely decorative Rococo.

His relationship with Luca Giordano is also significant. Solimena built upon Giordano's legacy, inheriting his position as Naples' leading painter. However, Solimena's work is often seen as more controlled and perhaps less exuberant than Giordano's famously rapid and fluid style ('Luca fa presto'). Solimena brought a greater degree of formal structure and meticulous finish to the Neapolitan tradition.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Francesco Solimena remained artistically active into his old age, dominating the Neapolitan art scene from the late 17th century until the 1740s. He died in Naples on April 3, 1747, at the venerable age of 89. His passing marked the end of an era for Neapolitan painting. His workshop and artistic legacy were continued, in part, by his nephew, Orazio Solimena, who followed in his footsteps as a painter.

Solimena's influence was profound and long-lasting. Through his own prolific output and the numerous students he trained, his style shaped the course of painting in Naples and significantly impacted artistic developments elsewhere in Italy and Europe. He successfully synthesized the dramatic power of the High Baroque with emerging Rococo sensibilities, creating a distinctive late Baroque manner that was widely admired and imitated.

Although artistic tastes shifted towards Neoclassicism later in the 18th century, leading to a temporary decline in the appreciation of Baroque masters like Solimena, his historical importance has long been recognized. His works remain key holdings in major museums and collections worldwide, including institutions in London, Paris, and St. Petersburg, testifying to his international stature during his lifetime and his enduring significance in the history of art. He is remembered as the last great master of the Neapolitan Baroque, a brilliant technician, a master of dramatic composition, and an influential teacher who guided a generation of artists. His self-portrait, mentioned as part of his estate, serves as a final testament to a long life dedicated to the art of painting. Anecdotal records also mention his charitable donations of art and cash, as well as his involvement in complex financial dealings, painting a picture of an artist deeply integrated into the social and economic fabric of his time.