Sebastiano Ricci stands as a pivotal figure in the transition from the grandeur of the High Baroque to the lighter elegance of the Rococo. Born in Belluno in the Republic of Venice on August 1, 1659, and dying in Venice on May 15, 1734, Ricci's prolific career spanned Italy and extended across Europe, revitalizing the Venetian school of painting with his vibrant palette, dynamic compositions, and masterful decorative schemes. His work, deeply rooted in the Venetian tradition yet open to diverse influences, left an indelible mark on eighteenth-century European art.

Early Life and Formative Years

Ricci's artistic journey began around the age of twelve or fourteen when he moved from Belluno to Venice. His initial apprenticeship was under Federico Cervelli, a painter whose style leaned towards the dramatic tenebrism influenced by Luca Giordano. This early exposure in Venice grounded Ricci in the city's rich artistic heritage, particularly the emphasis on color and light that characterized the works of masters like Titian and Tintoretto. However, Venice was only the first stop in his artistic education.

A tumultuous event marked Ricci's youth. In 1678, he was implicated in a scandal involving an unwanted pregnancy and an alleged attempt to poison the young woman involved to avoid marriage. This led to his imprisonment, from which he was reportedly released through the intervention of a nobleman, possibly from the influential Pisani family. This incident necessitated his departure from Venice, prompting a move that would prove crucial for his artistic development.

Ricci relocated to Bologna, a city renowned for its strong academic tradition rooted in the Carracci reforms. There, he entered the studio of Giovanni Gioseffo Dal Sole, a prominent painter of the Bolognese school. He also came into contact with, and likely collaborated with, Carlo Cignani, another leading figure whose style blended Bolognese classicism with Correggio's softness. In Bologna, Ricci absorbed the principles of structured composition and refined draughtsmanship, balancing the Venetian emphasis on colore with the Central Italian focus on disegno. His exposure to the works of the Carracci family, particularly Annibale Carracci, and the High Baroque master Pietro da Cortona, further shaped his evolving style.

Travels and Commissions Across Italy

Ricci's ambition and talent soon led him beyond Bologna. His early commissions included works like the Beheading of St. John the Baptist for the Confraternity of St. John of the Florentines in Bologna (around 1682). He worked in Parma around 1687-1688, executing commissions for the Duchess Farnese and undoubtedly studying the masterpieces of Correggio and Parmigianino, whose graceful figures and sfumato techniques left a visible imprint on his subsequent work.

The 1690s saw Ricci move further south. He spent time in Rome, absorbing the lessons of High Baroque masters like Pietro da Cortona and Giovanni Battista Gaulli (Baciccio). He worked on decorative frescoes, notably in the Palazzo Colonna, demonstrating his growing proficiency in large-scale, illusionistic ceiling painting. This Roman sojourn deepened his understanding of grand manner decoration and complex allegorical programs.

Following Rome, Ricci moved to Florence around 1694, where he received a significant commission from Grand Prince Ferdinando de' Medici. He worked extensively in the Palazzo Pitti, creating mythological and allegorical scenes. A particularly important project was the decoration of several rooms in the Palazzo Marucelli-Fenici (completed around 1706-1707), where his frescoes displayed a lighter, more airy quality, prefiguring the Rococo. His Florentine period also allowed him to further study Renaissance masters and engage with the city's vibrant artistic milieu. He also worked briefly in Milan during this period.

Throughout these travels, Ricci demonstrated a remarkable ability to synthesize diverse influences. He blended the rich colorism of the Venetians (especially Paolo Veronese, whose work he deeply admired and often emulated), the dynamic composition of the High Baroque (Cortona, Giordano), the grace of Correggio, and the academic structure of the Bolognese school into a distinctive personal style.

International Acclaim: Vienna, London, and Paris

By the turn of the century, Ricci's reputation had grown considerably, attracting patronage from beyond Italy. In 1702, he traveled to Vienna at the invitation of Emperor Leopold I. His most significant work there involved the decoration of the Blue Lacquer Room (or Millionenzimmer) in Schönbrunn Palace for Emperor Joseph I. These frescoes, depicting scenes from the life of Alexander the Great, are celebrated for their luminous colors, elegant figures, and sophisticated compositions, marking a high point in his decorative work and showcasing a style moving towards Rococo sensibilities.

After Vienna and a return to Italy (working again in Florence and Venice), Ricci embarked on another major international journey around 1711-1712, this time to England, likely encouraged by his nephew, the landscape painter Marco Ricci, who was already working there. In London, Ricci received prestigious commissions, including the Resurrection altarpiece for the chapel of the Royal Hospital Chelsea (completed around 1714) and paintings for Burlington House, the residence of the influential patron and architect Lord Burlington.

His time in England also involved a notable competition. Ricci vied with the English painter Sir James Thornhill for the commission to decorate the dome of St. Paul's Cathedral. Although Thornhill ultimately won the prestigious project, Ricci's presence and the quality of his work significantly impacted the English art scene, introducing a more vibrant and fluid Continental Baroque style. His paintings were highly sought after by English collectors and nobility.

During his return journey to Venice around 1716, Ricci likely passed through Paris. His fame preceded him, and in 1718, he was admitted to the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. This recognition underscored his international stature and his role in the broader European artistic exchange of the era. His style resonated with the emerging Rococo tastes favored by French artists like Antoine Watteau and François Boucher.

Return to Venice and Final Flourishing

Ricci spent the last two decades of his life primarily in Venice, enjoying immense prestige and a steady stream of commissions. He became a dominant figure in the city's artistic life, contributing significantly to the revival of large-scale decorative painting that had waned after the era of Veronese and Tintoretto. His workshop was highly productive, and he received commissions for numerous churches and palaces.

Notable works from this late period include paintings for the church of San Stae, where he contributed modelli for sculptures on the facade and painted the Liberation of Saint Peter. He also executed important works for San Zaccaria and the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. His style in these later years retained its characteristic brilliance and dynamism, often displaying an even greater lightness and fluidity, fully embracing the decorative potential of the Rococo aesthetic while maintaining Baroque energy.

He continued to receive honors, including election to the Accademia Clementina in Bologna in 1727. His influence extended through his own work and through his nephew Marco Ricci, with whom he sometimes collaborated, seamlessly integrating Marco's landscapes into his own figural compositions. Sebastiano Ricci died in Venice in 1734, leaving behind a rich legacy as one of the most accomplished and influential European painters of his generation.

Artistic Style and Technique

Sebastiano Ricci's style is characterized by its synthesis of various Italian artistic traditions, culminating in a vibrant Late Baroque manner that paved the way for the Rococo. His most defining feature is his use of color: bright, luminous, and applied with a fluid, painterly touch reminiscent of Paolo Veronese. He employed a high-keyed palette, often juxtaposing rich blues, reds, yellows, and whites to create dazzling effects.

Compositionally, Ricci favored dynamic arrangements, often using diagonal thrusts, swirling movement, and dramatic foreshortening to imbue his scenes with energy and theatricality. His figures, while elegant and graceful, possess a sense of vitality and movement derived from High Baroque masters like Pietro da Cortona and Luca Giordano. He excelled at handling complex multi-figure compositions, whether in large-scale frescoes or easel paintings.

Ricci masterfully employed light and shadow (chiaroscuro), though his approach generally favored clarity and brightness over the intense drama of Caravaggio or Rembrandt. Light serves to model forms, enhance color, and create atmospheric effects, contributing to the overall luminosity and airiness of his works, particularly in his later period.

His subject matter primarily encompassed religious, mythological, and historical themes, all treated with a sense of grandeur and decorative flair. He was particularly adept at depicting dramatic narratives and celestial visions, filling his canvases with animated figures, billowing drapery, and expansive architectural or landscape settings. His skill extended to both monumental fresco decorations, designed to integrate seamlessly with architecture, and smaller, highly finished oil paintings intended for private collectors.

Collaboration and Influence

While a master in his own right, Ricci occasionally collaborated with other artists. His most significant collaborator was his nephew, Marco Ricci (1676-1730). Marco specialized in landscape and architectural ruins, often providing evocative settings for Sebastiano's figures. Their joint works represent a harmonious blend of figure painting and landscape, popular among collectors. Sebastiano also collaborated earlier in his career with specialists like the quadratura painter Ferdinando Galli-Bibiena in Bologna.

Ricci's influence on subsequent generations was profound, particularly within Venice. He is widely considered a key figure in the resurgence of Venetian painting in the 18th century. His bright palette, fluid brushwork, and decorative sensibility directly inspired the greatest Venetian painter of the next generation, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Tiepolo adopted and further developed Ricci's airy compositions and luminous colors, bringing Venetian decorative painting to its zenith.

Other Venetian contemporaries and successors also felt his impact, including Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini and Jacopo Amigoni, who, like Ricci, enjoyed successful international careers. Even view painters like Canaletto and Francesco Guardi worked within the revitalized artistic environment that Ricci helped foster. His influence extended beyond Venice, impacting decorative painting trends in Austria, Germany, and England. Artists like Antonio Balestra and the pastel portraitist Rosalba Carriera were also part of this vibrant Venetian scene.

Key Works and Legacy

Sebastiano Ricci's oeuvre is vast and geographically dispersed. Among his most representative and celebrated works are:

Frescoes in the Palazzo Marucelli-Fenici, Florence (c. 1706-07): Mythological and allegorical scenes showcasing his move towards a lighter, proto-Rococo style.

Frescoes in Schönbrunn Palace, Vienna (c. 1702-04): Particularly the Blue Lacquer Room, demonstrating his mastery of grand decorative schemes for imperial patrons.

The Resurrection, Royal Hospital Chelsea, London (c. 1714): A major altarpiece from his English period, displaying his characteristic dynamism and color.

Finding of Moses (various versions, e.g., Royal Collection, UK): A popular subject treated with elegance and rich color.

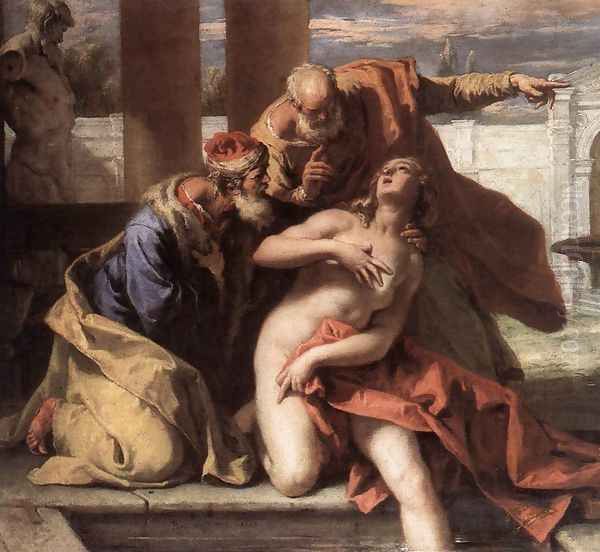

Susanna and the Elders (various versions, e.g., National Gallery, London): Demonstrating his skill in rendering dramatic narratives and the female form.

Venus and Adonis (e.g., Getty Museum, Los Angeles): A recurring mythological theme handled with sensuousness and pathos.

St. Gregory the Great Interceding for Souls in Purgatory, Sant'Alessandro della Croce, Bergamo (c. 1731): A powerful late religious work.

The Liberation of Saint Peter, San Stae, Venice (c. 1722-24): Part of a significant cycle by various artists, showcasing his mature Venetian style.

Assumption of the Virgin, Karlskirche, Vienna (c. 1734): One of his last major works, completed shortly before his death.

Sebastiano Ricci's legacy lies in his role as a bridge between the Baroque and Rococo, his revitalization of the Venetian painting tradition, and his creation of a vibrant, internationally influential style. He successfully synthesized the lessons of past masters with contemporary tastes, producing works characterized by dazzling color, dynamic composition, and decorative elegance. His influence, particularly on Tiepolo, ensured the continuation of the grand tradition of Venetian painting well into the 18th century, marking him as a crucial figure in European art history.

Conclusion

Sebastiano Ricci navigated the complex artistic landscape of late 17th and early 18th century Europe with remarkable skill and adaptability. From his early training in Venice and Bologna to his triumphant commissions across Italy, Austria, and England, he forged a distinctive style that captivated patrons and influenced fellow artists. His brilliant color, fluid brushwork, and dynamic compositions breathed new life into the Venetian school and played a significant role in the transition towards the Rococo aesthetic. As a master of both large-scale decoration and easel painting, Ricci left an enduring legacy, securing his place as one of the last great exponents of the Italian Baroque and a key precursor to the decorative splendors of the 18th century.