The 18th century was a period of immense artistic flourishing, particularly in France, where the Rococo style reached its zenith before giving way to Neoclassicism. Within this vibrant milieu, the Eisen family, notably François Eisen and his more renowned son Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen, carved out their distinct artistic paths. While François Eisen laid a foundation rooted in Flemish traditions and religious art, it was Charles who would become one of the era's most prolific and recognizable illustrators, embodying the grace and charm of the Rococo aesthetic. This exploration delves into the lives and works of these two artists, seeking to distinguish their contributions and understand their place within the rich tapestry of 18th-century art.

François Eisen: The Flemish Patriarch

François Eisen, born around 1695, hailed from a Flemish artistic background, with his own father reportedly being a painter from Brussels. This heritage undoubtedly shaped his early artistic sensibilities. While detailed records of his formative years are somewhat scarce, it is known that François established himself as a painter and, to some extent, an engraver. He spent a significant period of his working life in Valenciennes, a city in northern France with strong Flemish cultural ties, where his son Charles would later be born.

François Eisen's oeuvre appears to have been significantly dedicated to religious commissions. Historical accounts mention his work for various religious orders and churches, particularly in Brussels. He is credited with painting altarpieces and sacred images for institutions such as the Béguines, the Brigittines, and the Ursulines. These commissions suggest a painter adept at conveying devotional themes, likely working in a style that blended late Baroque and emerging Rococo sensibilities, filtered through a Flemish lens. His work would have been characterized by the rich colors and dynamic compositions often associated with the art of the Southern Netherlands.

One notable, though perhaps less typical, work attributed to François Eisen is a symbolic portrait of Empress Maria Theresa. This painting reportedly depicted the Empress with her army and family members, serving as a powerful statement of dynastic strength and political alliance. Such a commission, if accurately attributed, would indicate a broader range of subject matter than solely religious scenes and point to a reputation that extended to significant patrons.

François Eisen's direct influence was most profoundly felt in the upbringing of his son, Charles, to whom he provided initial artistic training. While François may not have achieved the widespread international fame of some of his contemporaries, his role as a practicing artist and a progenitor of an artistic lineage is an important aspect of his legacy. He passed away in 1778, the same year as his more famous son.

Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen: The Rococo Illustrator Par Excellence

Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen, often referred to simply as Charles Eisen, was born in Valenciennes in 1720. He received his foundational artistic education from his father, François, before venturing to Paris to further hone his skills. In the French capital, a bustling center of art and culture, Charles Eisen entered the studio of the esteemed engraver Jacques-Philippe Le Bas. Le Bas was a master of his craft, known for his reproductive engravings after contemporary painters like Jean-Baptiste Oudry and for his lively genre scenes. This apprenticeship was crucial in shaping Charles Eisen's proficiency in drawing and the techniques of printmaking, which would become central to his career.

Eisen's talent did not go unnoticed. He possessed a facile hand and a keen understanding of the prevailing Rococo taste, characterized by its elegance, charm, and often playful sensuality. His abilities as a draughtsman led to prestigious appointments. He became a drawing master to Madame de Pompadour, the influential mistress of King Louis XV and a paramount patron of the arts. This connection provided him with access to the highest echelons of French society and numerous opportunities. He was also appointed dessinateur du Roi (Draughtsman to the King).

His ambition extended to official recognition within the Parisian art establishment. Eisen sought membership in the Académie de Saint-Luc, a guild for painters and sculptors that offered an alternative to the more exclusive Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. After some initial difficulties, reportedly involving fee disputes that required legal intervention, he successfully joined the Académie de Saint-Luc around 1750, where he would later hold a position as an assistant professor. His works were also exhibited, including at the Salon of the Académie de Saint-Luc.

The Zenith of Book Illustration: Charles Eisen's Masterpieces

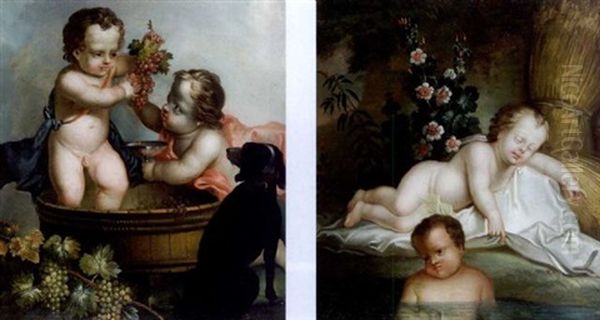

While Charles Eisen produced paintings, including mythological and allegorical scenes like "Hercule et Omphale" (Hercules and Omphale) and "L'Automne" (Autumn), his most enduring fame rests upon his prolific work as a book illustrator. In an era when illustrated books were highly prized luxury items, Eisen emerged as one of the foremost artists in this field. His designs, translated into engravings by skilled printmakers, adorned some of the most celebrated literary editions of the mid-18th century.

Perhaps his most famous achievement in book illustration is his work for the "Fermiers Généraux" edition of Jean de La Fontaine's Contes et Nouvelles en vers (Tales and Novellas in Verse), published in 1762. This lavish, two-volume edition is considered a masterpiece of Rococo book production. Eisen provided numerous designs for full-page illustrations and charming vignettes, which were then engraved by artists such as Aliamet, Baquoy, Choffard, and de Longueil. His interpretations of La Fontaine's often risqué tales are filled with wit, elegance, and a delicate eroticism that perfectly captured the spirit of the text and the tastes of the time. These illustrations are celebrated for their graceful figures, intricate compositions, and the seamless integration of image and text.

Eisen's talents were sought after for a wide array of publications. He provided illustrations for Voltaire's epic poem La Henriade, Ovid's Metamorphoses, and the works of Boccaccio. He also illustrated Claude Joseph Dorat's Les Baisers (The Kisses, 1770), a collection of poems. While his work for Dorat was considered elegant, some critics of the time, and later art historians, found his style in this particular publication less refined than that of his contemporary and rival in illustration, Hubert-François Gravelot. Gravelot, who had spent time in England and influenced artists like Thomas Gainsborough, was another leading figure in French book illustration, known for his delicate and precise style.

Other notable works illustrated by Eisen include editions of Torquato Tasso and an architectural treatise, Essai sur l’Architecture, for which he provided an allegorical frontispiece. His designs were not limited to literary works; he also created decorative patterns and designs for various applications, showcasing his versatility. The sheer volume of his output was remarkable, and his illustrations appeared in a vast number of important French books of the period.

Artistic Style, Influences, and Contemporaries

Charles Eisen's artistic style is firmly rooted in the Rococo. His drawings and designs are characterized by flowing lines, graceful figures often depicted in dynamic or languid poses, and a light, airy atmosphere. He had a particular skill for composing intricate scenes within the confined spaces of book pages, often employing asymmetrical arrangements and decorative flourishes typical of the Rococo. His figures, whether mythological deities, amorous couples, or historical personages, exude an undeniable charm and elegance.

A significant influence on Eisen's style was François Boucher, one of the leading Rococo painters of the era. Boucher's sensuous depictions of mythological scenes, pastoral idylls, and portraits of courtly figures set the tone for much of French art in the mid-18th century. Eisen absorbed Boucher's penchant for graceful curves, delicate color palettes (when his designs were intended for painting or colored prints), and charming subject matter. However, Eisen's work, particularly in illustration, often possessed a more intimate and delicate quality, suited to the smaller scale of the book.

Eisen worked within a vibrant community of artists in Paris. Besides his teacher Jacques-Philippe Le Bas and the influential Boucher, he was a contemporary of other prominent Rococo artists such as Jean-Honoré Fragonard, whose playful and erotic scenes share some affinities with Eisen's illustrations. Other notable figures in the world of French illustration and engraving during this period included Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger, a prolific draughtsman and engraver who also documented courtly life, and Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune, who became famous for his detailed depictions of Parisian society and customs. Jean-Baptiste Oudry, known for his animal paintings and tapestry designs, was also a significant book illustrator, particularly for editions of La Fontaine's Fables.

The competitive landscape of book illustration meant that artists like Eisen were often compared to their peers. While his work was immensely popular, some critics, then and later, occasionally found his output to be uneven or his figures sometimes lacking in the profound grace or "nobility" attributed to artists like Gravelot. Nevertheless, his ability to capture the spirit of the Rococo and his sheer productivity made him an indispensable figure in 18th-century publishing.

Challenges, Later Years, and Demise

Despite his successes and prestigious connections, Charles Eisen's career was not without its difficulties. Sources suggest that his personal life may have been somewhat tumultuous. He reportedly fell out of favor with Madame de Pompadour, possibly due to a "dissolute lifestyle" or behavior deemed inappropriate for the courtly circles in which he moved. Such a loss of patronage would have had significant financial and professional repercussions.

The art world itself was also undergoing changes. By the 1770s, the Rococo style was beginning to wane as the more austere and morally serious Neoclassical movement, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David (though David's major impact would be slightly later), gained traction. This shift in taste may have affected the demand for Eisen's particular brand of Rococo charm.

In 1776, the Académie de Saint-Luc, with which Eisen had been closely associated, was dissolved. This event, part of broader reforms in the organization of trades and guilds, likely impacted many artists who relied on such institutions for status and commissions. Around 1777, perhaps facing declining prospects in Paris or seeking a change of environment, Charles Eisen moved to Brussels, the city with strong ties to his family's Flemish origins.

Unfortunately, his time in Brussels was short-lived and reportedly marked by declining health and continued financial struggles. Charles Dominique Joseph Eisen died in Brussels in 1778, the same year as his father, François. Some accounts suggest he died in poverty, a poignant end for an artist who had once enjoyed the patronage of the French court and whose work had graced some of the most luxurious publications of his time.

The Enduring Legacy of the Eisen Family

Assessing the legacy of the Eisen family requires distinguishing between the contributions of father and son. François Eisen, the elder, was a competent painter in the Flemish tradition, contributing primarily to religious art in Valenciennes and Brussels. His direct legacy is perhaps most clearly seen in the initial artistic training he provided to his son and in the surviving examples of his devotional works, which offer a glimpse into the regional artistic production of his time.

Charles Eisen, on the other hand, achieved a far wider and more lasting reputation. His name is inextricably linked with the golden age of French Rococo book illustration. His designs for La Fontaine's Contes, Voltaire's Henriade, and numerous other works set a standard for elegance and charm that defined the genre in the mid-18th century. His illustrations not only enhanced the texts they accompanied but also served as influential visual interpretations that shaped how these literary works were perceived by contemporary audiences.

The delicacy, wit, and technical skill evident in Charles Eisen's drawings and the engravings made after them continue to be admired by collectors, scholars, and art enthusiasts. His work provides an invaluable window into the aesthetic sensibilities and cultural preoccupations of 18th-century France. While the Rococo style eventually gave way to Neoclassicism, the charm and artistry of Charles Eisen's illustrations ensured their enduring appeal. Artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Lancret had earlier set the stage for the Rococo's playful elegance, and Eisen, alongside contemporaries like Boucher and Fragonard, carried this spirit into the realm of graphic arts with remarkable success. Even later artists, such as Vincent van Gogh, are noted in some art historical accounts to have found inspiration in the design principles of earlier French illustrators, a testament to the lasting power of their visual language.

In conclusion, while François Eisen represents a more localized, traditional artistic practice, his son Charles Eisen rose to become a significant figure in the international art world of the 18th century. Charles's prolific output and his mastery of Rococo illustration left an indelible mark on the history of graphic arts, ensuring that the Eisen name, particularly his, remains recognized for its contribution to the elegance and refinement of a bygone era. Their combined story reflects the transmission of artistic skill within a family and the differing paths to recognition in a dynamic and evolving art world.