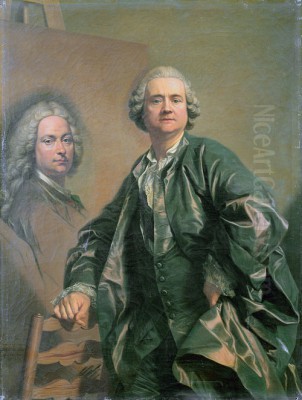

Louis-Michel van Loo stands as a significant figure in eighteenth-century European art, a master portraitist whose career bridged the courts of Spain and France. Born into an extraordinary artistic dynasty, his life and work reflect the grandeur, elegance, and intricate social networks of the Ancien Régime. While perhaps overshadowed in later art historical narratives by proponents of more overtly sensual Rococo or dramatic Neoclassicism, Van Loo's technical brilliance, his ability to capture likeness and status, and his prolific output secured his position as one of the most sought-after painters of his time. His portraits remain invaluable documents of the personalities and power structures that defined mid-eighteenth-century Europe.

An Artistic Dynasty: The Van Loo Family

Understanding Louis-Michel requires acknowledging the remarkable artistic lineage from which he emerged. The Van Loo family, of Dutch origin, established a veritable dynasty of painters whose influence spread across Europe for generations. The patriarch, Jacob van Loo (c. 1614–1670), was a notable painter of the Dutch Golden Age who later fled to Paris. His son, Louis-Abraham van Loo (c. 1653–1712), continued the tradition.

Louis-Abraham's sons, Jean-Baptiste van Loo (1684–1745) and Charles-André van Loo, known as Carle van Loo (1705–1765), achieved even greater fame. Jean-Baptiste, Louis-Michel's father, was a highly successful portraitist and history painter who worked in France, Italy, and England. Carle van Loo, Louis-Michel's uncle, became one of the most dominant figures in French art during the reign of Louis XV, eventually holding the prestigious position of Premier peintre du Roi (First Painter to the King).

Louis-Michel (1707–1771) was Jean-Baptiste's eldest son, born in Toulon, France. He, along with his younger brother Charles-Amédée-Philippe van Loo (1719–1795), who would later become court painter to Frederick the Great of Prussia, carried the family's artistic mantle into the next generation. This dense network of familial talent provided Louis-Michel not only with his initial training but also with invaluable connections and a deep understanding of the art world's mechanics.

Early Life and Training

Louis-Michel's artistic education began under the direct tutelage of his accomplished father, Jean-Baptiste. Growing up surrounded by studio practice, discussions of technique, and the business of art gave him a practical foundation few could rival. He absorbed the family's style, which blended Dutch precision with French elegance and an understanding of Italian composition gleaned from their travels and studies.

His formal training progressed within the established academic system. He studied at the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in Paris, the central institution governing art in France. His talent was recognized early; in 1725 (some sources cite 1726), he won the prestigious Prix de Rome, an award that funded study at the French Academy in Rome. This was a critical step for any ambitious young artist, offering exposure to classical antiquity and the masters of the Italian Renaissance and Baroque.

Between approximately 1727 and 1732, Louis-Michel spent time in Italy, notably in Rome and Turin. He traveled with his uncle Carle, further strengthening their artistic bond. During this period, he honed his skills, studying the works of Italian masters and likely absorbing influences from contemporary Roman artists. Some accounts suggest he studied directly under Benedetto Luti (1666-1724), a prominent Florentine painter working in Rome, known for his soft sfumato and graceful figures, although Luti's death date makes a prolonged tutelage unlikely; perhaps he studied Luti's work or associated with his studio. This Italian sojourn was crucial in refining his technique and broadening his artistic horizons beyond the French tradition.

The Spanish Court: Years in Madrid

A pivotal moment in Louis-Michel van Loo's career arrived in 1736 when he was summoned to Madrid. Philip V, the first Bourbon king of Spain (grandson of France's Louis XIV), sought to emulate the artistic splendor of the French court at Versailles. French artists were often favored, and the Van Loo name carried significant weight. Louis-Michel was appointed Pintor de Cámara, court painter to the King, succeeding Jean Ranc who had died tragically in a fire.

His arrival marked the beginning of a highly productive period lasting until 1752. Van Loo quickly established himself as the leading portraitist at the Spanish court. He was tasked with creating official likenesses of the royal family, nobility, and high-ranking officials. His style, characterized by meticulous detail, rich color, luxurious rendering of fabrics and jewels, and a sense of formal dignity, perfectly suited the requirements of royal portraiture.

During his time in Madrid, Van Loo played a significant role beyond just painting. He was instrumental in the foundation of a formal art academy modeled on the French system. In 1744, preparatory meetings led to the establishment of the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1752, the year Van Loo departed. He served as one of its directors, helping to shape artistic education in Spain for generations to come. This involvement demonstrates his standing not just as a painter but as an influential figure in the institutional art world.

His Spanish period produced one of his most ambitious and famous works: The Family of Philip V (1743). This monumental group portrait, now housed in the Prado Museum, depicts the King, his second wife Elisabeth Farnese, and their children, along with Philip's children from his first marriage. It is a masterpiece of composition and detail, showcasing Van Loo's ability to manage a complex arrangement of figures while rendering individual likenesses and the opulent textures of court attire and decor. The painting served as a powerful statement of dynastic continuity and royal authority, blending French elegance with Spanish formality.

Return to Paris: Premier Peintre du Roi

In 1752, Louis-Michel van Loo returned to Paris, his reputation greatly enhanced by his successful tenure at the Spanish court. He was readily admitted into the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. His return coincided with a flourishing period for the arts under Louis XV, though tastes were slowly evolving. The grand Baroque style was yielding to the lighter, more intimate Rococo, championed by artists like François Boucher (1703-1770) and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806).

Van Loo, however, largely maintained a more formal, though still elegant, style suited to official portraiture. He quickly gained favor at the French court. He painted numerous portraits of King Louis XV, members of the royal family, and prominent figures of the aristocracy and the Enlightenment. His skill in capturing not just a physical likeness but also the sitter's rank and persona made him highly sought after.

His career reached its zenith in 1765 when, following the death of his uncle Carle van Loo, Louis-Michel was appointed Premier peintre du Roi. This was the highest official artistic position in France, placing him at the head of the artistic establishment. Concurrently, he also succeeded his uncle as director of the École Royale des Élèves Protégés, a special school affiliated with the Académie designed to prepare the most promising students (often winners of the Prix de Rome) for their studies in Italy. These appointments solidified his status as a leading figure in the French art world.

Master of the Portrait

Portraiture was undeniably Louis-Michel van Loo's métier. His approach combined the meticulous realism inherited from his Dutch forebears with the elegance and compositional grace favored in France, refined by his Italian studies. He excelled at capturing the textures of materials – the shimmer of silk, the intricate patterns of lace, the gleam of polished armor, the sparkle of jewels, and the softness of velvet. These details were not mere embellishments; they were crucial signifiers of the sitter's wealth, status, and identity within the rigid social hierarchy of the time.

His official state portraits, such as those of Louis XV, often employed the conventions of the genre established by predecessors like Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659–1743) and Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746). The monarch is presented in ceremonial robes or armor, surrounded by symbols of power – columns, drapery, crowns, scepters. Van Loo masterfully integrated the figure within these imposing settings, often using grand architectural backgrounds to enhance the sense of majesty. His compositions are typically balanced and clear, the lighting designed to illuminate the face and highlight the luxurious details of the costume.

Beyond royalty, Van Loo painted portraits of aristocrats, ministers, and intellectuals. One of his most celebrated works is the Portrait of Denis Diderot (1767), the influential Enlightenment philosopher and editor of the Encyclopédie. This portrait is notable for its departure from stiff formality; Diderot is depicted in a relatively informal pose, seated at his desk, seemingly paused in thought, quill pen nearby. While still conveying intellectual authority, the portrait offers a more intimate glimpse of the sitter's personality, showcasing Van Loo's versatility.

Key Works Analyzed

Several works stand out in Louis-Michel van Loo's extensive oeuvre, illustrating his skill and the scope of his commissions.

The Family of Philip V (1743): As mentioned, this enormous canvas (measuring over 4 by 5 meters) is a landmark of Spanish Bourbon portraiture. Van Loo skillfully arranges fourteen figures in a richly decorated interior, likely inspired by Velázquez's Las Meninas in its complexity and spatial depth. Each individual is clearly delineated, their features captured with precision. The rendering of the diverse fabrics – silks, velvets, lace, and embroidered brocades – is extraordinary. The painting functions as both a collective dynastic image and a series of individual portraits, demonstrating Van Loo's organizational and technical prowess.

Louis XV, King of France and Navarre (c. 1760-1763): Van Loo painted Louis XV numerous times. A famous example, now at Versailles, depicts the king in his coronation robes. Standing full-length, Louis XV exudes regal authority, yet Van Loo subtly captures a sense of the man beneath the crown – perhaps a hint of the weariness noted by contemporaries. The meticulous rendering of the ermine-lined blue velvet robe, embroidered with gold fleurs-de-lis, the glittering crown and scepter, and the ornate furniture are hallmarks of Van Loo's official style. These portraits were widely copied and disseminated, shaping the public image of the monarch.

Portrait of Denis Diderot (1767): Commissioned by Catherine the Great of Russia, this portrait, now in the Louvre, is considered one of the most iconic images of the Enlightenment thinker. Van Loo presents Diderot without a wig, dressed in simple indoor attire, leaning thoughtfully on his arm amidst the tools of his trade – books and papers. The direct gaze and naturalistic pose create a sense of intellectual presence and accessibility rare in formal portraiture of the era. Diderot himself, however, famously critiqued the portrait, feeling it made him look like an "old coquette," highlighting the complex relationship between artist, sitter, and representation.

These examples demonstrate Van Loo's range, from the grand formality required by state commissions to the more nuanced character studies of individuals like Diderot. His consistent technical excellence is evident across his work.

Teaching and Influence

As director of the École Royale des Élèves Protégés and a professor at the Académie Royale, Louis-Michel van Loo played an active role in educating the next generation of artists. The French academic system emphasized rigorous training based on drawing from casts, live models, and the study of Old Masters. Van Loo, with his extensive experience in France, Italy, and Spain, was well-positioned to guide students.

His time in Madrid also left a lasting mark. His involvement in founding the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando helped institutionalize French academic principles in Spain, influencing Spanish art for decades. While Francisco Goya (1746-1828) would later forge a radically different path, the academic structures Van Loo helped establish formed the backdrop against which Goya initially developed.

One specific student associated with Van Loo's Madrid workshop is Luis Egidio Meléndez (1716–1780). Although Meléndez primarily worked as a copyist of Van Loo's royal portraits during his time there (a common practice for disseminating official images), he later emerged as arguably Spain's greatest still-life painter of the eighteenth century. While their artistic paths diverged significantly, Meléndez's early exposure to Van Loo's meticulous technique and attention to detail may have informed his own later precision in rendering everyday objects. Other Spanish artists, like Miguel Jacinto Meléndez (Luis Egidio's uncle, though more a contemporary/competitor than student), were also active during Van Loo's time in Madrid.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Competitions

The eighteenth-century art world was a competitive environment, particularly for portraitists vying for prestigious commissions. Louis-Michel van Loo operated alongside many talented contemporaries. In France, his main rivals in portraiture included Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766), known for his idealized and allegorical portraits of court ladies; Louis Tocqué (1696–1772), Rigaud's son-in-law, noted for his realistic and psychologically astute portraits; the pastel specialists Maurice Quentin de La Tour (1704–1788) and Jean-Baptiste Perronneau (1715–1783); and the Swedish painter Alexander Roslin (1718–1793), who enjoyed immense success in Paris with his dazzling depictions of fabrics.

While competition was fierce, collaboration also occurred. The creation of large-scale decorative schemes or the production of artworks often involved multiple specialists. Van Loo is known to have collaborated with craftsmen like the goldsmith Jacques Roettiers, reflecting the interconnectedness of the arts under court patronage. His family connections also represented a form of built-in collaboration and support network, unique in its scope and influence.

Evidence suggests Van Loo was aware of his competitors and protective of his status. An anecdote relates his criticism of the portraitist Jean Laboury, whom he apparently deemed technically deficient, indicating the professional rivalries and critical judgments common among artists of the period. His position as Premier Peintre placed him at the apex, but required constant navigation of court politics and artistic trends.

Artistic Style and Technique

Louis-Michel van Loo's style is best characterized as a refined and elegant form of late Baroque or early Rococo classicism, primarily applied to portraiture. His Dutch heritage likely contributed to his meticulous attention to detail and texture. His Italian training instilled a sense of compositional structure and idealized grace. His French context demanded elegance, sophistication, and adherence to the protocols of court representation.

Technically, he was highly accomplished. His brushwork is typically smooth and controlled, allowing for precise rendering of features and materials. He masterfully handled light and shadow to model form and create a sense of presence. His color palettes are rich and harmonious, often employing deep reds, blues, and golds for official portraits, reflecting the luxury of his sitters' attire and surroundings.

While capable of capturing psychological nuance, as seen in the Diderot portrait, his primary focus, especially in state commissions, was on conveying dignity, status, and an idealized version of the sitter. He excelled at what art historians call the "portrait d'apparat" – the ceremonial portrait where costume, setting, and pose are carefully orchestrated to project power and social standing. This required not just artistic skill but also a keen understanding of social codes and symbolism.

Legacy and Art Historical Reception

Louis-Michel van Loo died in Paris in 1771, at the height of his official career. He left behind a vast body of work, primarily portraits, that document the elite society of mid-eighteenth-century France and Spain. His immediate legacy was significant; he held the highest artistic posts, influenced academic training, and his portraits shaped the visual identity of monarchs and influential figures.

However, his posthumous reputation has fluctuated. The late nineteenth century, particularly under the influence of critics like the Goncourt brothers, tended to favor the more overtly sensual or intimate aspects of Rococo found in artists like Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), Boucher, or Fragonard. Van Loo's more formal, official style was sometimes dismissed as academic or lacking in originality. His technical perfection could be seen as coldness, his adherence to convention as conservatism.

Twentieth and twenty-first-century art history has taken a more balanced view. While acknowledging that Van Loo was not a radical innovator, scholars recognize his exceptional skill, his importance within the court systems of France and Spain, and the value of his work as historical documents. His portraits are studied for their insights into eighteenth-century fashion, social hierarchy, and the representation of power. His role in the establishment of the San Fernando Academy in Madrid is also acknowledged as a significant contribution to Spanish art history.

In conclusion, Louis-Michel van Loo was a consummate professional, a master technician, and a key figure in the artistic landscape of eighteenth-century Europe. Born into a dynasty of painters, he navigated the complex worlds of the Spanish and French courts with skill and diplomacy, rising to the highest official positions. His portraits, characterized by meticulous detail, rich color, and formal elegance, captured the likenesses and status of kings, queens, aristocrats, and intellectuals, leaving behind an invaluable visual record of his time. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, his artistry and influence solidify his place as a major portrait painter of the Ancien Régime.