François-Marius Granet (1775-1849) occupies a distinct and fascinating place in the history of French art. Born in the sun-drenched city of Aix-en-Provence, his life spanned a tumultuous period in France, witnessing the Revolution, the rise and fall of Napoleon, the Restoration, and the July Monarchy. Trained in the Neoclassical tradition but drawn to the atmospheric potential of light and shadow, Granet forged a unique path, becoming particularly renowned for his evocative depictions of architectural interiors, especially those he encountered during a long and formative stay in Rome. His work bridges the structured ideals of Neoclassicism with the burgeoning sensibility of Romanticism, leaving behind a legacy preserved notably in the museum bearing his name in his hometown.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Provence and Paris

Born on December 17, 1775, François-Marius Granet grew up in Aix-en-Provence, a city rich in history and culture. His father was a master stonemason, a background that perhaps instilled in the young Granet an early appreciation for structure and form, elements that would later resonate in his architectural paintings. His mother was described as an artist, suggesting a home environment where creative pursuits were valued. From an early age, Granet displayed a pronounced passion for drawing and painting, sketching the landscapes and ancient structures of his native Provence.

His formal artistic education began locally under the guidance of Jean-Antoine Constantin, a landscape painter from Marseille, not Italy as sometimes mistakenly suggested. Constantin was known for his depictions of the Provençal countryside, and his tutelage likely honed Granet's observational skills and his ability to capture the specific light and atmosphere of the South of France. However, the ambition of a young artist in late 18th-century France inevitably led towards Paris, the epicenter of the art world.

Granet made his way to the capital and entered the prestigious studio of Jacques-Louis David. This was a pivotal moment. David was the leading figure of French Neoclassicism, his studio a crucible where rigorous drawing, compositional clarity, and themes drawn from classical antiquity and republican virtue were paramount. Studying under David provided Granet with a strong foundation in academic technique and exposed him to the dominant artistic ideology of the time.

Within David's circle, Granet not only absorbed Neoclassical principles but also formed crucial connections. He befriended fellow artists and importantly, met Auguste de Forbin, a nobleman, painter, and future museum director who would become a lifelong friend and influential supporter. This network, forged in the competitive yet collaborative environment of David's studio, would prove invaluable throughout Granet's career. While absorbing David's lessons, Granet's own artistic inclinations towards more intimate, atmospheric scenes began to subtly diverge from the grand historical narratives favored by his master.

A Revolutionary Interlude: The Siege of Toulon

Granet's artistic development was briefly interrupted by the dramatic events of the French Revolution. In 1793, at the age of eighteen and lacking financial resources, he volunteered for the Republican army during the critical Siege of Toulon. This port city had rebelled against the Republic and was occupied by Royalist forces supported by British and Spanish fleets. Granet was assigned duties in the arsenal, placing him amidst the machinery of war.

This period offered an unexpected, formative encounter. Granet met a young artillery captain named Napoleon Bonaparte, the future Emperor. According to Granet's memoirs, Bonaparte invited him to dinner, where they discussed matters unrelated to the immediate conflict. This brief interaction left an impression and perhaps laid groundwork for future, albeit indirect, patronage connections.

More profoundly, the siege itself was a harsh lesson in reality. Granet witnessed the intense fighting and, after the Republican victory, the subsequent destruction and brutal reprisals within the captured city. This exposure to conflict and its aftermath likely tempered the young artist, adding a layer of lived experience that subtly informed the often quiet, contemplative mood of his later works, even those depicting serene monastic interiors. After the siege, he continued his military service for a time before fully returning to his artistic path.

The Roman Years: A Defining Chapter

In 1802, Granet embarked on a journey that would profoundly shape his artistic identity: he traveled to Rome. Initially intended as a shorter study trip, common for ambitious artists seeking to immerse themselves in classical antiquity and the works of the Renaissance masters, Granet's stay extended for an extraordinary twenty-two years, lasting until 1824. Rome became his second home and the primary source of inspiration for his most characteristic works.

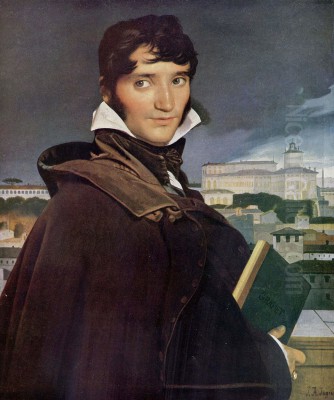

He quickly integrated into the vibrant international community of artists residing in the city. Rome, despite the political upheavals of the Napoleonic era, remained a powerful magnet for painters, sculptors, and architects from across Europe. Granet found camaraderie and intellectual stimulation among fellow French artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who also spent a significant period in Italy, as well as artists from other nations, all drawn by the city's unparalleled artistic heritage. They often gathered in shared studios or residences, sometimes in former monastic buildings, studying and sketching together.

During his Roman sojourn, Granet developed the themes and style that would define his career. While he continued to paint landscapes and historical subjects, he became increasingly fascinated by architectural interiors, particularly the atmospheric spaces within churches and monasteries. He spent countless hours sketching in locations like the Basilica of Saint Francis of Assisi, the Colosseum, and various Roman churches, paying close attention to the play of light and shadow within these ancient and sacred structures.

His particular focus became the depiction of monastic life, especially scenes set within Capuchin monasteries. He was captivated by the quiet rhythms of religious observance, the textures of aged stone, and the dramatic effects of light filtering through high windows into dimly lit chapels and choir stalls. These scenes resonated with a sense of history, piety, and tranquility that appealed strongly to contemporary tastes, offering a contrast to the turbulence of the recent past.

The Breakthrough: The Choir of the Capuchin Church

Granet's dedication to these interior scenes culminated in his breakthrough work, Le Chœur de l'église des capucins à Rome (The Choir of the Capuchin Church in Rome). Exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1819, the painting was an immediate and sensational success. It depicted Capuchin friars gathered for prayer, enveloped in the deep shadows of their church choir, with shafts of light dramatically illuminating parts of the architecture and the figures. The painting's mastery of chiaroscuro, its evocative atmosphere, and its perceived spiritual depth captivated the public and critics alike.

The success was so significant that the painting was acquired by Caroline Murat, Napoleon Bonaparte's sister and the Queen of Naples. This prestigious patronage cemented Granet's reputation. The demand for the image was such that Granet produced numerous replicas – sources suggest as many as sixteen – varying slightly in detail but retaining the core composition and atmospheric effect. This work became his signature piece, widely disseminated through engravings and establishing his fame across Europe.

Other works from his Roman period explored similar themes, such as depictions of artists within historical settings, like Stella Painting the Virgin on his Prison Wall or scenes related to the life of the painter Sodoma. He also continued to produce exquisite watercolors and drawings of Roman monuments and landscapes, often using brown ink washes to achieve subtle tonal variations and capture the specific quality of Italian light. His friendship with patrons like the Genoese nobleman Giovanni Battista Cattaneo provided support during these productive years.

Artistic Style: Light, Shadow, and Atmosphere

François-Marius Granet's artistic style is characterized by a unique synthesis of his Neoclassical training and a more personal, Romantic sensibility, expressed primarily through his masterful manipulation of light and his choice of subject matter.

Mastery of Light and Shadow (Chiaroscuro): This is arguably Granet's most defining characteristic. He possessed an exceptional ability to render the subtle gradations of light and shadow, particularly within interior spaces. His paintings often feature dimly lit environments – church choirs, monastic cells, crypts, artists' studios – dramatically punctuated by focused sources of light, whether from a high window, a hidden lamp, or a doorway. This technique, reminiscent of Dutch Golden Age masters like Rembrandt van Rijn or Johannes Vermeer, was used not just for realistic effect but to create mood, focus attention, and imbue the scene with a sense of mystery or spirituality.

Religious and Monastic Themes: Granet frequently depicted scenes of religious life, but his approach was distinct. Rather than focusing on grand biblical narratives or iconic images of Christ and the saints in the manner of traditional religious painting, he concentrated on the human element within sacred spaces. He portrayed monks at prayer, artists working in chapels, or the quiet solitude of monastic cloisters. This indirect approach conveyed a sense of piety and historical continuity, often tinged with a nostalgic longing for a perceived stability and faith associated with the past, particularly appealing in the post-Revolutionary era.

Architectural Focus: His father's profession as a mason may have influenced his lifelong fascination with architecture. Granet rendered buildings, both intact and ruined (like his views of the Colosseum), with sensitivity to their structure, texture, and the way light interacted with their forms. His interiors are not mere backdrops but active participants in the composition, their arches, vaults, and columns shaping the space and guiding the viewer's eye. His attention to detail in depicting stonework, wood grain, and architectural ornamentation added to the realism and tactile quality of his scenes.

Neoclassical Roots vs. Romantic Sensibility: While trained by David in the rigors of Neoclassical drawing and composition, Granet's mature style moved towards a more Romantic expression. The emphasis shifted from didactic clarity and idealized form towards atmosphere, emotion, and the picturesque. His use of a often subdued, tonal palette, dominated by browns, ochres, and greys, contributed to the melancholic or contemplative mood of many works. His landscape sketches, particularly his watercolors, sometimes display a freedom and immediacy in capturing light effects that have led some later critics to see hints of pre-Impressionism.

Materials and Techniques: Granet was highly proficient in both oil painting and watercolor. His watercolors and ink washes, often executed with remarkable subtlety and transparency, were particularly admired. He frequently used brown ink and wash over graphite sketches, building up tones to create depth and luminosity. This technique allowed for both detailed rendering and broad atmospheric effects, perfectly suited to his preferred subjects.

Return to France: Official Recognition and Curatorial Roles

In 1824, after more than two decades in Italy, Granet returned to France. His reputation, largely built on the success of his Roman works, preceded him. He settled in Paris and soon received significant official recognition. His friend Auguste de Forbin was now the Director-General of the Royal Museums, which likely facilitated Granet's appointment as a Curator at the Musée du Louvre. This prestigious position acknowledged his standing in the art world and his connoisseurship.

His career received further accolades in 1830 when he was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts, one of the highest honors for a French artist. Under the July Monarchy of King Louis-Philippe, Granet was entrusted with a major project: the creation and direction of the new Musée de l'Histoire de France (Museum of French History) housed in the Palace of Versailles. Opened in 1837, this vast museum aimed to reconcile the nation with its complex past by illustrating French history through thousands of paintings and sculptures. Granet served as its first curator, overseeing the immense task of assembling, arranging, and displaying the collections.

These administrative roles inevitably consumed much of his time and energy, perhaps limiting his output as a painter compared to his prolific Roman years. However, he continued to paint and exhibit, sometimes revisiting his popular Roman themes or undertaking commissions related to his official duties. His work from this later period, while technically accomplished, perhaps lacked some of the innovative spark and intense focus of his Italian scenes.

Contemporaries and Artistic Circle

Throughout his long career, Granet moved within significant artistic circles, interacting with many of the leading figures of his time. His formative experience in Jacques-Louis David's studio placed him alongside other notable pupils who would shape French art, such as Antoine-Jean Gros, known for his Napoleonic battle scenes, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson, a painter with a distinct proto-Romantic style, and perhaps François Gérard and Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, though their paths diverged. His early friendship with Auguste de Forbin remained a constant, providing support and institutional connections later in life.

His extended stay in Rome brought him into close contact with Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, another giant of French painting who spent many years in Italy. While their styles differed – Ingres pursuing a refined linearity derived from Raphael, Granet focusing on light and atmosphere – they shared the experience of expatriate life and the deep study of Italian art. Granet's interactions likely extended to sculptors active in Rome, such as the internationally renowned Antonio Canova or Bertel Thorvaldsen, although painting remained his focus.

His patrons were also significant figures. Caroline Murat, Queen of Naples, provided a crucial early endorsement. Giovanni Battista Cattaneo offered friendship and support in Rome. Later, King Louis-Philippe became a major patron through the Versailles project. Granet's artistic influences, beyond his direct teachers like Constantin and David, clearly included Dutch masters like Rembrandt and Vermeer, and likely landscape traditions represented by artists such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, whose structured compositions may have informed his architectural views.

Later Years, Shifting Reputation, and Controversy

Despite the official honors and prestigious positions he held upon returning to France, Granet's artistic reputation experienced a gradual decline from its peak around 1820. The art world was changing rapidly, with Romanticism gaining ascendancy and new artistic concerns emerging. While his mastery of light was still acknowledged, his focus on monastic interiors and his somewhat conservative style began to seem less relevant to some critics and collectors.

A notable instance of negative reception occurred at the Paris Salon of 1834. Some critics found his religious paintings overly pious or sentimental, even accusing them of "hypocrisy" in a France that was navigating complex secular and religious tensions. This criticism, combined with the changing artistic landscape, contributed to his work being somewhat overshadowed in the later decades of his career. His fame became more localized, particularly strong in his native Provence.

The political upheaval of the 1848 Revolution, which overthrew the July Monarchy, prompted Granet, then in his early seventies, to retire from his official duties. He left Paris and returned to the city of his birth, Aix-en-Provence, seeking the familiar surroundings and tranquility of his youth. He spent his final year in Aix, surrounded by the landscapes that had first inspired him.

Legacy and the Musée Granet

François-Marius Granet died in Aix-en-Provence on November 21, 1849. His most enduring legacy, apart from his significant body of work, is the museum that bears his name in his hometown. During his lifetime and through his will, Granet bequeathed a substantial portion of his personal art collection, including many of his own paintings and drawings, as well as works by other artists he owned, to the city of Aix.

This generous donation formed the core of the city's art museum, which was subsequently renamed the Musée Granet in his honor. Today, it houses the most important collection of Granet's works anywhere, offering a comprehensive overview of his career, from early sketches to major Roman paintings and later works. It allows visitors to appreciate the consistency of his vision and the evolution of his technique. The museum also holds works by his contemporaries and later artists, including another famous son of Aix, Paul Cézanne, who studied Granet's paintings in the museum as a young man and admired his predecessor's handling of structure and light.

After a period of relative obscurity following his death, Granet's reputation began to revive in the 20th century. Art historians and curators reassessed his contribution, recognizing the unique quality of his vision, his technical brilliance, particularly in watercolor, and his significant role as a transitional figure between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. His evocative depictions of light-filled interiors and his sensitive rendering of architectural spaces secured his place as a distinctive master within the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art.

Conclusion

François-Marius Granet stands as a testament to the power of a singular artistic vision pursued with dedication over a long career. Grounded in the discipline of Neoclassicism, he found his true voice in the atmospheric interiors and historical settings of Rome, becoming a celebrated master of light and shadow. His depictions of monastic life, imbued with a quiet spirituality and historical resonance, captured the imagination of his contemporaries. Though his fame fluctuated during his lifetime and after, his substantial body of work, particularly his sensitive watercolors and evocative oils, reveals a consistent artistic temperament drawn to tranquility, structure, and the transformative power of light. Through his paintings and his foundational bequest to the Musée Granet, François-Marius Granet left an indelible mark on French art history, his work continuing to resonate with viewers drawn to its quiet beauty and masterful execution.