François Pascal Simon Gérard stands as a pivotal figure in French art history, a painter whose career spanned the tumultuous decades from the French Revolution through the Napoleonic Empire and into the Bourbon Restoration. Born in Rome on March 12, 1770, to a French father serving as an official at the French embassy and an Italian mother, Gérard's life and art became intrinsically linked with the destiny of France. He died in Paris on January 11, 1837, leaving behind a legacy defined by masterful portraiture and significant historical paintings, executed primarily within the Neoclassical tradition.

Gérard's artistic journey began not in painting, but sculpture. He initially received instruction in Paris from the sculptor Augustin Pajou. However, his true calling lay with the brush, leading him to the studio of the preeminent Neoclassical painter of the era, Jacques-Louis David. Under David's tutelage, Gérard flourished, quickly becoming one of his master's most talented and favored assistants. This apprenticeship was crucial, embedding in Gérard the core tenets of Neoclassicism: clarity of line, balanced composition, noble subjects, and a certain moral gravity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gérard's early life presented significant challenges that undoubtedly shaped his character and resolve. Born abroad, he moved to Paris at a young age. His formative years were marked by personal loss; the early death of his parents left him responsible for his younger brother, Jacques-Alexandre Gérard, who would also pursue a career as a painter before his own premature death in 1832. Navigating these difficulties, often in conditions of poverty, Gérard remained steadfast in his commitment to art, honing his skills within the competitive environment of David's studio.

The studio of Jacques-Louis David was the epicenter of French painting in the late 18th century. It was not merely a place of instruction but a crucible where artistic doctrine was forged and political ideas debated. To be a favored pupil of David meant absorbing the master's rigorous technique, his emphasis on drawing, and his preference for subjects drawn from classical antiquity and republican virtue. Gérard excelled in this environment, mastering the Neoclassical style while beginning to develop his own distinct sensibility.

Ascendancy in Turbulent Times

Gérard began to make his mark during the revolutionary period. An early work mentioned in connection with his rising reputation was related to the events of August 10, 1792, though his major breakthrough came slightly later. His painting Belisarius, exhibited in 1795, demonstrated his command of the Neoclassical idiom, depicting the blinded Byzantine general with pathos and dignity. This work signaled his arrival as a serious contender on the Parisian art scene.

Also in 1795, Gérard painted the remarkable portrait Jean-Baptiste Isabey and his Daughter. Isabey, a fellow artist (a renowned miniaturist and portrait painter) and also a student of David, was a close associate of Gérard. This painting, noted for its blend of Neoclassical clarity and a burgeoning sense of intimacy and individual character, further enhanced Gérard's reputation. It showcased his ability to work within the established style while infusing his subjects with life.

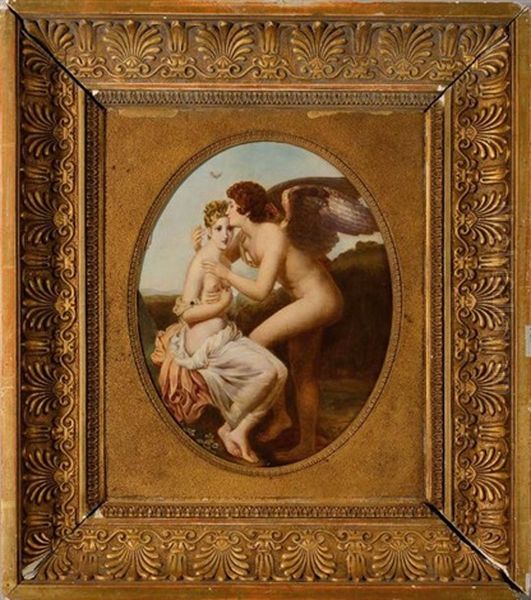

His fame solidified with the exhibition of Cupid and Psyche (also known as Psyché et l'Amour) at the Salon of 1798. This work, now housed in the Louvre Museum, became one of his most celebrated paintings. Depicting the mythological lovers with exquisite grace and tenderness, it perfectly captured the refined elegance that would become a hallmark of Gérard's style. The painting was highly praised, distinguishing Gérard even amongst the talented cohort emerging from David's studio, which included artists like Antoine-Jean Gros and Anne-Louis Girodet.

Portraitist of the First French Empire

The rise of Napoleon Bonaparte provided Gérard with unparalleled opportunities. As Napoleon consolidated power, first as Consul and then as Emperor, he and his court required artists to craft their public image. Gérard, with his elegant Neoclassical style and proven skill in portraiture, was perfectly positioned to meet this demand. He was appointed as an official painter to the Imperial court, a prestigious role that brought him numerous commissions.

During the Empire, Gérard became the portraitist of choice for the new elite. He painted Napoleon himself, Empress Joséphine, and numerous members of the extended Bonaparte family and the Imperial court. His portrait of Empress Joséphine captured her renowned grace and fashion sense. He also painted figures connected to the Imperial circle, such as Camillo Borghese, the Roman prince who married Napoleon's sister Pauline. These portraits were not mere likenesses; they were carefully constructed images of power, status, and refinement, perfectly suited to the aspirations of the Napoleonic regime.

His success was reflected in his prominence at the Paris Salons, the crucial public exhibitions of the time. At the Salon of 1808, he exhibited an impressive eight paintings, and in 1810, he presented fourteen works. This level of visibility confirmed his status as one of the most sought-after and fashionable painters in Paris. His studio became a hub, attracting patrons from across Europe.

Beyond portraiture, Gérard also undertook major historical commissions celebrating the Empire's triumphs. One significant example is The Battle of Austerlitz, painted around 1806-1810 for the Galerie des Batailles at the Palace of Versailles. This large-scale work depicted one of Napoleon's greatest military victories, showcasing Gérard's ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and dramatic historical narratives, albeit within the structured framework of Neoclassicism.

Artistic Style: Elegance and Refinement

François Gérard's art is fundamentally rooted in the Neoclassicism he learned from Jacques-Louis David. This is evident in the clarity of his drawing, the smooth finish of his surfaces (the fini), the often balanced and stable compositions, and his frequent engagement with historical and mythological subjects. However, Gérard adapted the Neoclassical style, infusing it with a distinctive elegance, grace, and psychological nuance that set his work apart.

Compared to the often severe and didactic style of David, Gérard's Neoclassicism is generally softer and more sensuous. His lines, while pure, often flow with greater fluidity. His color palettes could be rich and saturated, contributing to the luxurious feel of many of his portraits. He excelled at rendering textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of velvet, the gleam of jewels – enhancing the sense of realism and opulence demanded by his elite clientele.

In his portraiture, Gérard demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture not only a physical likeness but also the sitter's personality and social standing. He was particularly adept at portraying women, capturing their elegance, poise, and the fashionable styles of the day. His Madame Récamier (1802, though sometimes dated 1805), now in the Louvre, is an iconic example. It depicts the famous society beauty reclining on a chaise longue, embodying the Neoclassical ideal of grace and simplicity, yet rendered with a palpable sense of individual presence and contemporary chic. This portrait is often compared to David's own unfinished portrait of the same sitter, highlighting Gérard's more polished and perhaps more flattering approach.

While firmly Neoclassical, some scholars detect elements in Gérard's work that anticipate or overlap with Romanticism. This might be seen in the subtle emphasis on individual feeling in his portraits, or in the slightly more dynamic compositions and emotional atmosphere of some of his mythological or historical works compared to stricter Neoclassical precedents. He navigated a path that retained classical structure while allowing for greater sensitivity and charm, a combination that proved immensely popular. His contemporaries included artists exploring different facets of Neoclassicism and early Romanticism, such as the dramatic Napoleonic scenes of Gros, the unique classicism of Girodet, and the softer, more atmospheric style of Pierre-Paul Prud'hon.

The Bourbon Restoration and Later Career

The fall of Napoleon in 1814-1815 did not spell the end of Gérard's success. Unlike his master David, who went into exile, Gérard skillfully navigated the political transition to the Bourbon Restoration. His reputation for elegant portraiture remained intact, and he found favor with the restored monarchy. King Louis XVIII recognized his talent and status, appointing him First Painter to the King and granting him the title of Baron in 1819.

Gérard continued to receive prestigious commissions from the new regime and the aristocracy. He painted official portraits of King Louis XVIII and his successor, King Charles X. He also painted other members of European royalty and nobility who flocked to his Paris studio. His ability to convey status and refinement remained highly valued, ensuring his continued prominence.

During this period, he also completed significant historical paintings. The Entry of Henry IV into Paris (1817), commissioned for the Palace of Versailles, depicted a key moment in French royal history, a theme well-suited to the Restoration's emphasis on legitimist history. This large canvas demonstrated his continued skill in managing grand compositions and historical detail.

He also returned to mythological themes, as seen in Daphnis and Chloe (1824), another work now in the Louvre. This painting revisits the pastoral romance with the characteristic grace and smooth finish of his earlier successes. Another notable work from his oeuvre is The Three Ages of Man (1806), which later came into the collection of King Louis-Philippe and is now housed in the Simón Bolívar Foundation in Mexico City.

Despite this continued success and official recognition, some accounts, including information from the provided source text, suggest that Gérard's absolute preeminence perhaps waned slightly in the later years compared to his Imperial peak. The source also notes that in his later life, Gérard expressed some regret that his fame rested so heavily on portraiture, feeling he had not achieved as much as he might have wished in the more highly esteemed genre of history painting. His output also slowed in his final years due to declining health.

Analysis of Key Works

Several of Gérard's paintings stand out as particularly representative of his style and contribution:

Cupid and Psyche (1798): This early masterpiece exemplifies Gérard's elegant Neoclassicism. The composition is balanced, the figures idealized according to classical prototypes, yet imbued with a gentle sensuality and tenderness. The smooth, porcelain-like finish of the skin and the delicate rendering of light and shadow are characteristic. It can be compared to contemporary sculptural treatments of the theme, such as those by Antonio Canova, highlighting the shared Neoclassical interest in mythological love stories rendered with grace.

Madame Récamier (1802/1805): This portrait is an icon of Empire style and feminine elegance. Gérard presents Juliette Récamier in a simple white gown, reclining in a pose inspired by classical antiquity, yet thoroughly modern in its sensibility. The painting captures her celebrated beauty and social grace, making it a defining image of the era. It cemented Gérard's reputation as the premier portraitist of elegant women.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey and his Daughter (1795): Significant as an early success, this double portrait demonstrates Gérard's ability to combine Neoclassical formality with a sense of personal connection. The depiction of his friend and fellow artist Isabey with his young daughter has an intimacy that complements the clarity of line and controlled composition.

The Battle of Austerlitz (c. 1806-1810): Representing his work in the grand genre of history painting, this canvas tackles the complexity of a major battle scene. While adhering to Neoclassical principles of organization and clarity, it aims to convey the drama and significance of Napoleon's victory. Such works were crucial for the visual propaganda of the Empire.

Entry of Henry IV into Paris (1817): This later history painting shows Gérard adapting his skills to the political climate of the Restoration. The subject celebrates the return of legitimate monarchy, rendered with historical detail and compositional grandeur, suitable for its placement in the historical galleries at Versailles.

Connections, Contemporaries, and Influence

François Gérard's career cannot be understood in isolation. His primary influence was undoubtedly Jacques-Louis David, whose studio shaped a generation of French artists. Gérard, along with Antoine-Jean Gros, Anne-Louis Girodet, and later Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, formed the core of the Neoclassical school in France, though each developed a distinct style. Gérard maintained a friendly relationship with fellow David student Jean-Baptiste Isabey. His own brother, Jacques-Alexandre Gérard, was also a painter, though less famous.

Gérard operated within a vibrant artistic milieu. He competed for commissions and acclaim with other portraitists, including earlier established figures like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who, although associated with the Ancien Régime, continued to work into the 19th century. His elegant style can be contrasted with the more dramatic or Romantic tendencies emerging in the work of artists like Théodore Géricault and Eugène Delacroix later in his career. He was also contemporary with major Neoclassical sculptors like the Italian Antonio Canova and the Danish Bertel Thorvaldsen, who similarly enjoyed pan-European fame and patronage from figures like Napoleon.

While perhaps not as revolutionary an innovator as David or Ingres, Gérard's influence lay in his perfection of a particular kind of Neoclassical portraiture – elegant, refined, psychologically astute, and technically brilliant. He set a standard for court portraiture across Europe. His ability to adapt and thrive through successive political regimes also speaks to his skill and diplomacy.

Legacy and Re-evaluation

François Gérard was one of the most successful and celebrated painters of his time. His legacy rests primarily on his extraordinary body of portraiture, which provides an invaluable visual record of the leading figures of French society during a period of profound transformation. From the revolutionaries to the Imperial court to the restored monarchy, Gérard captured the faces of an era.

His work embodies a specific moment in the evolution of Neoclassicism, blending its formal rigor with a grace and sensitivity that appealed widely to the tastes of his time. While his reputation may have been somewhat overshadowed in the later 19th century by the rise of Romanticism and subsequent movements, the source material indicates a re-evaluation of his work occurred, particularly with the advent of Modernism, leading to renewed appreciation for his technical skill and historical importance.

Today, Gérard's paintings are held in the collections of major museums worldwide, including the Louvre Museum and the Palace of Versailles in France, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and many others. His works continue to be sought after on the art market, testament to their enduring appeal and historical significance. He remains a key figure for understanding the art, politics, and society of France from the 1790s through the 1830s.

Conclusion

François Pascal Simon Gérard navigated the shifting tides of French history with remarkable success, establishing himself as a leading painter of the Neoclassical era. Trained by David, he developed a distinctive style characterized by elegance, technical polish, and psychological insight. As the favored portraitist of the Napoleonic Empire and later the Bourbon Restoration, he created iconic images of the era's elite. While also accomplished in historical and mythological painting, it is his portraits that constitute his most enduring legacy, offering a refined and captivating window onto a transformative period in European history. His art represents a masterful blend of Neoclassical principles with a sensitivity that ensured his popularity during his lifetime and secures his place as a significant figure in the history of French painting.