Louis Hersent (1777-1860) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of French art during the tumultuous late 18th and early 19th centuries. Born in Paris, a city then on the cusp of revolutionary upheaval and soon to become the epicenter of European artistic innovation, Hersent's career spanned the decline of Neoclassicism, the rise of Romanticism, and the establishment of the academic tradition that would dominate much of the century. As a painter of historical subjects, mythological scenes, and, notably, portraits, he carved out a successful career, navigating the shifting tastes of patrons and the critical landscape of the Parisian Salons. His work, characterized by technical proficiency and a sensitivity to his subjects, offers a valuable lens through which to view the artistic currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Revolutionary Era

Born on March 10, 1777, Louis Hersent's formative years coincided with the dramatic events of the French Revolution. This period of profound social and political transformation inevitably shaped the cultural environment in which he would develop as an artist. Paris, even amidst chaos, remained a vibrant center for artistic training. Hersent showed early promise and was fortunate to become a pupil of the preeminent master of Neoclassicism, Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825).

David's studio was the crucible of French painting in the late 18th century, a place where rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and classical principles was paramount. Under David's tutelage, Hersent would have absorbed the tenets of Neoclassicism: clarity of form, emphasis on line, noble and serious subject matter drawn from classical history or mythology, and a commitment to moral didacticism. The influence of David was profound, shaping not only Hersent's technical skills but also his initial thematic preoccupations.

The Prestigious Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A testament to his talent and the quality of his training, Hersent achieved a significant milestone early in his career: in 1797, he was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome. This coveted prize, granted by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (later the Académie des Beaux-Arts), provided young artists with a scholarship to study at the French Academy in Rome. For aspiring painters, sculptors, and architects, a period in Rome was considered an essential component of their education.

The Italian sojourn offered unparalleled opportunities to study firsthand the masterpieces of classical antiquity and the High Renaissance. Exposure to the works of artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, and the classical sculptors whose works filled Roman collections would have deepened Hersent's understanding of form, composition, and idealized beauty. This experience was crucial in solidifying the Neoclassical foundations of his art, even as he would later incorporate elements more aligned with emerging Romantic sensibilities.

Salon Debuts and Shifting Thematic Focus

Upon his return to Paris, Louis Hersent began to establish his reputation through regular participation in the Parisian Salons. The Salon, an official, juried exhibition, was the primary venue for artists to display their work, attract patrons, and gain critical recognition. Hersent made his Salon debut in 1802 with a painting titled The Metamorphosis of Narcissus. This choice of subject, drawn from Greek mythology, was typical of a young artist trained in the Neoclassical tradition.

Initially, Hersent's oeuvre was dominated by mythological and classical scenes. Works from this period often showcased his strong draftsmanship, balanced compositions, and an idealized treatment of the human form, all hallmarks of his Davidian training. However, as his career progressed, and as the political and cultural landscape of France continued to evolve through the Napoleonic Empire and the Bourbon Restoration, Hersent's thematic range expanded. He increasingly turned his attention to historical subjects, particularly those drawn from French history, including the reign of Louis XVI and events of the Napoleonic era.

Master of Historical Painting

Hersent's historical paintings were noted for their meticulous attention to detail, careful research into costume and setting, and their ability to convey dramatic narratives. One of his most celebrated works in this genre is Louis XVI Distributing Alms to the Poor During the Harsh Winter of 1788, exhibited at the Salon of 1817. This painting, created during the Bourbon Restoration, served a clear political purpose, aiming to present the executed king in a compassionate and benevolent light, thereby bolstering the legitimacy of the restored monarchy. The work is characterized by its sentimental appeal and its focus on royal virtue, themes that resonated with the prevailing mood of the Restoration period.

Another significant historical painting, The Monks of Saint Gothard (also known as The Hospice of Saint Bernard), painted in 1824, depicts monks and their famous dogs rescuing travelers in the snowy Alps. This work, while still demonstrating a strong compositional structure, incorporates elements of Romanticism, particularly in its dramatic setting, its emphasis on human emotion, and its theme of humanitarianism in the face of nature's power. It highlights Hersent's ability to adapt his style to evolving tastes, blending Neoclassical clarity with Romantic expressiveness.

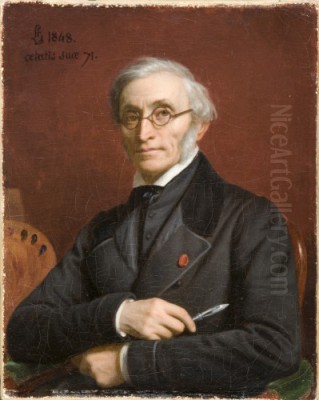

Acclaimed Portraitist of an Era

While his historical and mythological paintings secured his academic reputation, Louis Hersent also excelled as a portrait painter. In an era that saw the rise of a new aristocracy under Napoleon and the re-establishment of the old nobility during the Restoration, there was a considerable demand for portraiture. Hersent's portraits were highly sought after by the elite of French society.

His skill lay in his ability to capture not only a faithful likeness but also the character and social standing of his sitters. He painted numerous prominent figures, including members of the royal family, aristocrats, intellectuals, and fellow artists. His portraits are characterized by their refined elegance, subtle psychological insight, and meticulous rendering of textures and fabrics.

Among his notable portraits are those of Sophie Gay (1824), a prominent writer and salonnière, and her daughter, Delphine Gay (later Delphine de Girardin), also a respected literary figure. These portraits are sensitive and insightful, capturing the intelligence and grace of his subjects. He also painted Maria Amalia Teresa of Naples and Sicily, Queen of France, wife of Louis-Philippe I, in 1831. This royal commission underscores his status as a favored portraitist of the ruling class. His style in portraiture, while maintaining a degree of Neoclassical formality, often allowed for a greater intimacy and a more nuanced exploration of individual personality than was typical in his grander historical compositions.

Navigating Neoclassicism and Romanticism

Louis Hersent's artistic career unfolded during a period of significant stylistic transition in European art. He was trained in the Neoclassical tradition, which, under the leadership of his master Jacques-Louis David, had become the dominant artistic language of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Neoclassicism emphasized reason, order, clarity, and moral virtue, drawing inspiration from the art of ancient Greece and Rome.

However, by the early 19th century, the emotional intensity, individualism, and emphasis on imagination characteristic of Romanticism began to challenge Neoclassical hegemony. Artists like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) with his groundbreaking Raft of the Medusa (1819), and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), with works like The Barque of Dante (1822) and Liberty Leading the People (1830), championed a more dynamic, colorful, and emotionally charged approach to painting.

Hersent, while firmly rooted in his Neoclassical training, was not immune to these evolving currents. His work often exhibits a careful balance between the two styles. While his compositions remained structured and his figures often idealized in the Neoclassical manner, his later works, particularly in their choice of subject, emotional content, and sometimes in their handling of color and light, show an engagement with Romantic themes and sensibilities. He can be seen as a transitional figure, one who adapted the principles of Neoclassicism to suit the changing tastes of the early to mid-19th century, incorporating elements that appealed to a growing Romantic sensibility without fully abandoning his classical foundations. This nuanced position allowed him to maintain a successful career across different political regimes and artistic climates.

Other notable works that illustrate his stylistic range include Achilles Parting from Briseis (exhibited 1806), a subject from Homeric epic that allowed for both classical heroism and emotional drama. Daphnis and Chloe (1817) explored pastoral romance, a theme popular in both classical and romantic traditions. His earlier mythological work, Atala in the Arms of Cupid (or similar titles focusing on Atala, a character from Chateaubriand's Romantic novel), if accurately attributed and dated, would further point to an early engagement with Romantic literary sources, though Las Casas malade soignée par les sauvages (1808), depicting the Spanish missionary Bartolomé de las Casas being cared for by indigenous people, certainly touches upon themes of exoticism and humanitarianism that resonated with Romantic thought.

Hersent as a Teacher and His Influence

Like many successful artists of his time, Louis Hersent also played an important role as a teacher, running a studio that attracted numerous aspiring painters. The master-apprentice system was still central to artistic education, and established artists like Hersent were responsible for passing on their knowledge and skills to the next generation. His studio would have provided training in drawing, painting techniques, and composition, likely following the academic principles he himself had learned from David.

Among his pupils were artists who would go on to establish their own careers, though perhaps not reaching the same level of fame as the students of David or later masters. Some of his known students include Louis-Marie-Eugène Bertier, Auguste Bigand, Jacques-Raymond Brascassat (known for animal painting), Louise Adélaïde Desnos (who also became a friend and documented his studio), Félicie de Fauveau (a notable female sculptor who initially studied painting with him), and Antoine François Mauduit. The presence of female students like Desnos and Fauveau in his circle is noteworthy for the period.

Through his teaching, Hersent contributed to the continuity of the French academic tradition. While the art world was evolving rapidly, the foundational skills and classical principles he imparted remained relevant. His influence, therefore, extended beyond his own canvases to the work of those he trained. He was also married to Marie-Jeanne-Louise Mauduit, who herself was a painter, particularly of miniatures, and exhibited under the name Louise Hersent. This artistic partnership likely enriched his personal and professional life.

Contemporaries and the Parisian Art World

Louis Hersent operated within a vibrant and competitive Parisian art world. He was a contemporary of some of the most celebrated names in French art. Besides the towering figures of David, Géricault, and Delacroix, other notable artists of his era included Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), another prominent pupil of David who became a staunch defender of Neoclassicism and a rival to Delacroix. Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), also a David student, became famous for his Napoleonic battle scenes, infusing them with a proto-Romantic dynamism.

Pierre-Paul Prud'hon (1758-1823) offered a softer, more sensual alternative to Davidian Neoclassicism, often characterized by his sfumato technique. François Gérard (1770-1837) was a highly successful portraitist and historical painter, much like Hersent. The Vernet dynasty, including Carle Vernet (1758-1836) and his son Horace Vernet (1789-1863), were immensely popular for their battle scenes, genre paintings, and Orientalist subjects. Jean-Baptiste Isabey (1767-1855) was a renowned miniaturist and portrait painter, particularly active during the Napoleonic era.

Hersent's interactions with these artists, whether as colleagues, competitors, or influences, shaped his career. The Salons were arenas where these diverse talents were showcased, and critical debates about style and subject matter were common. Hersent's ability to consistently exhibit and receive commissions in this environment speaks to his skill and adaptability.

Later Career, Recognition, and Critical Reception

Louis Hersent enjoyed a long and productive career, continuing to exhibit at the Salon until 1831. He received numerous honors and official commissions, reflecting his esteemed position within the French art establishment. He was elected a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in 1822, a significant mark of recognition from his peers. He was also appointed a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts, further cementing his role as an influential figure in academic art education.

While he achieved considerable success and was popular with patrons, particularly the emerging bourgeoisie and the restored aristocracy, his work was not without its critics, especially as Romanticism gained ascendancy. Some later critics, particularly those championing the more radical innovations of Delacroix or, later, the Realists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877), might have viewed Hersent's art as too conventional or academic. There are mentions of him receiving negative criticism for technical aspects in the 1831 Salon, which may have contributed to his decision to cease exhibiting there regularly.

However, his sustained success over several decades indicates that his blend of Neoclassical discipline and restrained Romantic sentiment appealed to a significant segment of the art-buying public and the official arbiters of taste. His ability to produce dignified portraits and engaging historical narratives ensured his continued relevance.

Legacy and Enduring Significance

Louis Hersent passed away in Paris on October 2, 1860. He left behind a substantial body of work that reflects the artistic transitions of his era. While he may not be as widely known today as some of his more revolutionary contemporaries like Géricault or Delacroix, or his iconic master David, Hersent's contribution to French art is undeniable.

His paintings are held in numerous French museums, including the Louvre, the Palace of Versailles, and various regional museums. These works serve as important documents of their time, offering insights into the tastes, values, and historical events of early 19th-century France. His portraits, in particular, provide a visual record of the prominent personalities who shaped the era.

Hersent's legacy also lies in his role as a bridge between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. He demonstrated that it was possible to adapt the rigorous principles of academic training to new thematic and emotional demands. As a respected teacher, he also played a part in shaping the next generation of artists, contributing to the continuity of the French artistic tradition.

In the broader narrative of art history, Louis Hersent exemplifies the successful academic painter of the early 19th century – skilled, adaptable, and attuned to the demands of his patrons and the official art institutions. His career highlights the complexities of an art world in transition, where established traditions coexisted and interacted with emerging movements. A re-evaluation of his work allows for a more nuanced understanding of the diverse artistic landscape of France during a pivotal period of its history. His dedication to his craft, his technical mastery, and his ability to capture the spirit of his age ensure his place in the annals of French art.