Frank Bramley stands as a significant figure in the narrative of British art during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A pivotal member of the Newlyn School, he was celebrated for his evocative portrayals of rural life, his mastery of light, and his contribution to the development of Post-Impressionist tendencies in Britain. His journey from the quiet fields of Lincolnshire to the vibrant artist colonies of Cornwall and the hallowed halls of the Royal Academy reflects a period of dynamic change and exploration in European art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Sibsey, a village near Boston in Lincolnshire, England, in 1857, Frank Bramley's artistic inclinations emerged early. His formal training commenced at the Lincoln School of Art, where he studied from 1873 to 1878. This foundational education would have provided him with the essential skills in drawing and composition, typical of provincial art schools of the era, which often emphasized rigorous academic discipline.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Bramley, like many ambitious young British artists of his generation, looked to the continent. From 1879 to 1882, he enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. This institution was a magnet for international students, drawn by its strong academic tradition that still bore the influence of Flemish Old Masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, but was also adapting to contemporary trends. In Antwerp, Bramley studied under Charles Verlat, a respected Belgian painter known for his historical scenes, animal paintings, and portraits. Verlat's tutelage would have reinforced a commitment to skilled draughtsmanship and a solid understanding of pictorial construction. The Antwerp academy, at this time, was also a place where students were exposed to the burgeoning realist movements sweeping across Europe, particularly the influence of French artists.

The Call of Newlyn: An Artist Colony in Cornwall

After his continental studies, Bramley spent some time in Venice from 1882 to 1884, a city that had captivated artists for centuries with its unique light and picturesque scenery. Figures like J.M.W. Turner and James McNeill Whistler had famously found inspiration there. However, it was upon his return to England in 1884 that Bramley made a decision that would define his career: he settled in Newlyn.

Newlyn, a fishing village on the coast of Cornwall in the far southwest of England, had begun to attract a community of artists. Drawn by the dramatic coastal scenery, the quality of the light, and the perceived authenticity of the local fishing community's life, these painters sought to escape the industrialization and academic constraints of London. They were inspired by the French plein air (open-air) painters of the Barbizon School, such as Jean-François Millet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, and particularly by the social realism of artists like Jules Bastien-Lepage, whose depictions of rural peasant life resonated deeply.

Bramley quickly became a central figure in what became known as the Newlyn School. He joined a burgeoning group of like-minded artists who were already establishing themselves or arriving around the same time. This artistic fraternity included Stanhope Forbes, often considered the "father" of the Newlyn School, and his future wife Elizabeth Armstrong (later Elizabeth Forbes), Walter Langley, who was one of the earliest to settle in Newlyn, Thomas Cooper Gotch, Henry Scott Tuke, and Norman Garstin. These artists shared a commitment to painting contemporary life directly from nature and from the model, often working outdoors or in makeshift studios that allowed them to capture the nuances of natural light.

Life and Work in Newlyn

Bramley's time in Newlyn was incredibly productive and formative. He fully immersed himself in the local environment, choosing to live among the villagers to better understand their daily lives, struggles, and moments of quiet dignity. This deep engagement with his subject matter was a hallmark of the Newlyn School's approach, aiming for an honest and unsentimental portrayal of working-class life.

He, along with Stanhope Forbes and Walter Langley, was instrumental in shaping the direction and reputation of the Newlyn School. They would often paint together, sharing techniques and critiques, fostering a collaborative yet individually distinct artistic environment. Their subjects were the fishermen and their families, the bustling quayside, the intimate interiors of cottages, and the ever-present, often perilous, sea.

Bramley developed a particular skill for capturing complex lighting conditions, especially the interplay between natural and artificial light in interior scenes. This "square brush" technique, using distinct, visible brushstrokes to build up form and atmosphere, was characteristic of many Newlyn painters and showed an awareness of Impressionist handling, though their palette was often more subdued and their focus more on narrative and social realism than the fleeting optical effects central to French Impressionism as practiced by Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro.

A Hopeless Dawn: A Masterpiece of Social Realism

It was in Newlyn that Bramley created his most famous work, A Hopeless Dawn, completed in 1888. This painting depicts a young woman collapsed in grief at a table, comforted by an older woman, presumably her mother, while another woman, perhaps a sister or neighbour, peers anxiously through the cottage window at the stormy sea. A Bible lies open on the table, and an empty chair poignantly suggests the fisherman lost at sea. The scene is illuminated by the cold, grey light of dawn filtering through the window and the warm, flickering light of a lamp, showcasing Bramley's mastery in handling dual light sources.

A Hopeless Dawn was exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1888 and was met with critical acclaim. It was purchased for the Chantrey Bequest, a fund established to buy works of art for the nation, and is now in the collection of Tate Britain. The painting's emotional power, its sensitive portrayal of human tragedy, and its technical brilliance solidified Bramley's reputation and brought significant attention to the Newlyn School. It encapsulated the movement's concern with the harsh realities faced by fishing communities, where the sea was both a provider and a constant threat. The work resonated with Victorian audiences, who appreciated its narrative clarity and sentimental depth, but also its unvarnished depiction of working-class sorrow.

Other Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

While A Hopeless Dawn remains his most iconic piece, Bramley produced many other significant works during his Newlyn period and beyond. He often focused on themes of community, family, and the quiet dramas of everyday life. Paintings like Domino! (1886), showing a family gathered for a game, or Saved (1889), depicting the rescue of a shipwrecked sailor, further explored these themes.

His work often carried a strong social undercurrent. He was interested in the lives of ordinary people, particularly the women who waited anxiously for their men to return from the sea, and the elderly who faced an uncertain future. Fireside Tales (also known as The Chimney Story) is another example, showing an older woman sharing a story with a younger girl by the hearth, highlighting intergenerational connection and the oral traditions within these communities. This focus on social issues and the human condition aligned him with other socially conscious artists of the period, such as Luke Fildes or Hubert von Herkomer, though Bramley's approach was generally less overtly didactic and more observational.

Bramley's artistic style continued to evolve. While his early Newlyn works were characterized by a more detailed realism and a relatively sombre palette, his later paintings sometimes showed a brighter range of colours and a looser brushwork, indicating an increasing engagement with Impressionist principles, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere. This shift can be seen in works like Reading in the Garden (1909), which displays a lighter, more vibrant palette.

Later Career, Recognition, and Personal Life

In 1891, Frank Bramley married Katherine Graham, a fellow artist. The couple had three children. They initially lived at Belle Vue Cottage in Newlyn, a hub for artistic gatherings. However, by the mid-1890s, the initial impetus of the Newlyn School began to wane as artists moved on or developed in different directions. Bramley himself left Newlyn around 1895, moving first to Droitwich in Worcestershire and later to Grasmere in the Lake District, before finally settling at Chalford Hill in Gloucestershire.

Despite leaving Cornwall, Bramley continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy in London, a key venue for artists seeking national recognition. His talent was formally acknowledged when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1894, a significant honour. He achieved full Academician status (RA) in 1911. These accolades cemented his position within the British art establishment.

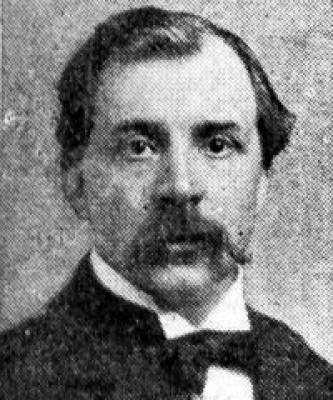

His circle of friends and colleagues extended beyond the Newlyn group. He maintained a friendship with William Wainwright, a Birmingham-based artist who painted a portrait of Bramley. His early training under Charles Verlat in Antwerp also connected him to a broader European academic tradition. While his direct interactions with French Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro are not well-documented, his stylistic development clearly shows an awareness of their innovations, likely absorbed through exhibitions, publications, and discussions with fellow artists who had spent time in Paris, such as Stanhope Forbes. He would also have been aware of the work of James McNeill Whistler, whose tonal harmonies and aesthetic concerns offered an alternative to both academic art and strict Impressionism.

A notable incident in his later career involved a disagreement with the influential artist and critic Walter Sickert, a leading figure in the Camden Town Group. This conflict reportedly led to Bramley's withdrawal from the New English Art Club (NEAC), an exhibiting society founded as a more progressive alternative to the Royal Academy, though many Newlyn painters, including Bramley, exhibited at both.

Artistic Style Revisited: Light, Colour, and Narrative

Bramley's enduring contribution lies in his sensitive and atmospheric depictions of human experience, particularly within domestic and rural settings. His early Newlyn works are characterized by their "square brush" technique, a method also employed by Stanhope Forbes and others, influenced by French painters like Bastien-Lepage. This involved using flat, square-ended brushes to apply paint in distinct patches, building up form and texture while retaining a sense of immediacy.

His palette, especially in the 1880s, often featured muted tones – greys, browns, and blues – which effectively conveyed the often-sombre mood of his subjects and the soft, diffused light of the Cornish coast. However, his genius truly shone in his handling of complex interior lighting. He masterfully balanced the cool, natural light from a window with the warm, artificial glow of a lamp or fire, creating scenes of great depth and emotional resonance. This technical skill set his work apart.

As he moved into the 20th century, his style showed a gradual shift. His brushwork became somewhat looser, and his palette brightened, reflecting a greater absorption of Impressionist influences. Works from this later period often feature sunnier outdoor scenes or more brightly lit interiors, though he never fully abandoned his commitment to narrative and human interest. He remained, at heart, a painter of people and their stories.

Legacy and Influence

Frank Bramley's health began to decline in his later years. He passed away in Chalford Hill, Gloucestershire, in August 1915, at the relatively young age of 58.

Today, Frank Bramley is remembered as one of the foremost figures of the Newlyn School and a significant British painter of his generation. His work successfully bridged the gap between Victorian narrative painting and emerging modern influences. He, along with Stanhope Forbes, Walter Langley, and others like T.C. Gotch and Henry Scott Tuke, helped to establish a distinctly British form of social realism infused with an appreciation for the effects of light and atmosphere. The Newlyn School itself had a lasting impact, inspiring subsequent generations of artists in Cornwall, including later figures associated with St Ives such as Lamorna Birch and, much later, the St Ives modernists like Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, though their artistic aims were vastly different.

His paintings are held in numerous public collections, including Tate Britain, the Royal Academy of Arts, Penlee House Gallery & Museum in Penzance (which has an excellent collection of Newlyn School works), Nottingham Castle Museum, and various regional galleries throughout the UK. These collections ensure that his contribution to British art continues to be appreciated.

Bramley's legacy is that of an artist who combined technical skill with profound empathy. He captured the dignity and hardship of ordinary lives, creating images that were both specific to their time and place, and universal in their emotional appeal. His exploration of light was innovative, and his role in the Newlyn School was crucial to its success and enduring influence on the course of British painting. He remains a testament to the power of art to illuminate the human condition with honesty and compassion.