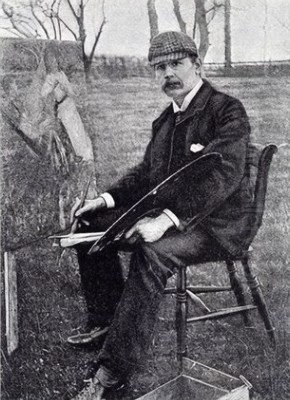

Henry Herbert La Thangue (1859-1929) stands as a significant figure in British art history, renowned primarily as a painter associated with rural realism and the burgeoning influence of French Naturalism and Impressionism on British shores. His career spanned a period of considerable artistic change, and he navigated these currents with a distinctive style characterized by vibrant light, textured brushwork, and a profound empathy for the lives of rural working people. A British national, La Thangue dedicated his professional life to painting, leaving behind a legacy of works that capture the essence of the countryside, both in England and Southern Europe, with remarkable sensitivity and technical skill.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Croydon, Surrey, near London, in 1859, Henry Herbert La Thangue came from a background with mixed European heritage; his father was of French Huguenot descent, and his mother was Irish. This connection to France would perhaps subtly predispose him to the artistic developments occurring across the Channel later in his life. His formal artistic education began at Dulwich College, a notable institution where he likely first honed his observational skills.

His talent was evident early on, leading him to the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. Here, he excelled, demonstrating a commitment that culminated in winning the coveted Gold Medal in 1879. This award came with a valuable scholarship, providing him with the means to further his studies abroad. During his time at the RA Schools, he formed important early friendships with fellow students who would also make their mark on British art, most notably Stanhope Forbes, who would become a lifelong friend and artistic compatriot. Another contemporary at Dulwich, though perhaps less closely associated later, was Frederick Goodall.

Following his success at the Royal Academy, La Thangue made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the time. He enrolled at the renowned École des Beaux-Arts, securing a place in the studio of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme was a highly respected, albeit traditional, academic painter known for his historical and Orientalist scenes. Studying under Gérôme provided La Thangue with rigorous training in drawing and composition, grounding him in academic discipline even as he began to absorb the more radical artistic ideas circulating in the French capital.

Embracing French Naturalism and Plein-Air Painting

Paris in the early 1880s was a crucible of artistic innovation. While La Thangue received academic training under Gérôme, he was inevitably exposed to the powerful currents of Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism. The influence of the Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-François Millet and Camille Corot, who had championed direct observation of nature and peasant life decades earlier, was still palpable. More immediately impactful was the work of contemporary French Naturalists, particularly Jules Bastien-Lepage.

Bastien-Lepage's meticulous yet atmospheric depictions of rural life, painted with a high degree of realism but also sensitivity to light and mood, resonated deeply with many younger artists, including La Thangue. This approach offered a compelling alternative to both staid academicism and the looser, more purely optical concerns of the Impressionists like Claude Monet. La Thangue embraced the Naturalist ethos, focusing on authentic portrayals of rural existence and adopting the practice of plein-air (open-air) painting.

A key moment in this development was his trip to Brittany in 1881, undertaken with his friend Stanhope Forbes. Brittany, with its rugged landscapes and traditional ways of life, was a popular destination for artists seeking authentic, 'unspoiled' subjects. Painting directly from nature, capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, became central to La Thangue's practice. This experience solidified his commitment to rural themes and the techniques required to render them convincingly outdoors.

The Newlyn Connection and the New English Art Club

Upon returning to Britain, La Thangue became associated with the burgeoning group of artists known as the Newlyn School, although he never permanently settled in the Cornish fishing village himself. His friend Stanhope Forbes was a central figure in establishing this colony, alongside others like Frank Bramley and Thomas Cooper Gotch. The Newlyn artists shared La Thangue's interest in depicting rural and coastal life with truthfulness, often focusing on the hardships and heroism of working people, and employing techniques influenced by French Naturalism and plein-air painting. La Thangue's work from this period certainly aligns with the Newlyn ethos.

La Thangue was also a key figure in challenging the established art institutions in Britain, particularly the Royal Academy. He felt, along with many of his contemporaries who had experienced the more progressive atmosphere of Paris, that the RA was too conservative and resistant to new artistic ideas. This dissatisfaction led to the formation of the New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1886.

While sources suggest he was involved in the initial discussions and attempts to reform the RA that preceded the NEAC's formal creation, and though he wasn't present at the very first meeting, La Thangue quickly became one of the NEAC's most prominent and, at times, controversial exhibitors. The NEAC provided a vital alternative venue for artists influenced by French developments, including figures like Philip Wilson Steer, Walter Sickert, and George Clausen, another painter deeply invested in rural themes. La Thangue's commitment to realism and modern techniques made his work central to the NEAC's early identity as a progressive force in British art.

Signature Style and Technique

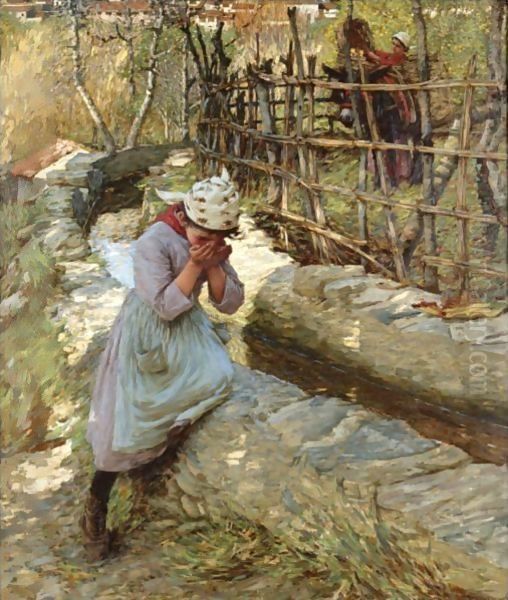

Henry Herbert La Thangue developed a highly individual painting style that blended meticulous observation with a vibrant handling of paint and light. One of his most distinctive technical features was his use of the "square brush" technique. This involved applying paint in relatively uniform, squarish dabs, creating a textured surface that effectively conveyed the vibration of light and the solidity of form without resorting to smooth, academic blending. This method, likely adapted from French influences, gave his canvases a lively, mosaic-like quality.

His palette was notable for its brightness and reliance on opaque colours. He masterfully captured the effects of natural light, whether the dappled sunlight filtering through leaves, the cool light of early morning, or the warm glow of late afternoon. His paintings often explore the interplay of light and shadow across figures and landscapes, demonstrating a keen sensitivity to atmospheric conditions and the changing seasons. This focus on light aligns him with Impressionist concerns, though his commitment to solid form and narrative detail often keeps him closer to the Naturalist camp.

In his early works, such as The Return of the Reapers (1886), some critics noted an interest in photographic realism, suggesting he may have used photographic aids – a practice not uncommon among realist painters seeking accuracy. However, his painterly technique always remained paramount, preventing his work from becoming mere photographic transcription. He favoured painting directly onto the canvas, often without extensive preliminary drawings, working alla prima to capture the immediacy of the scene before him.

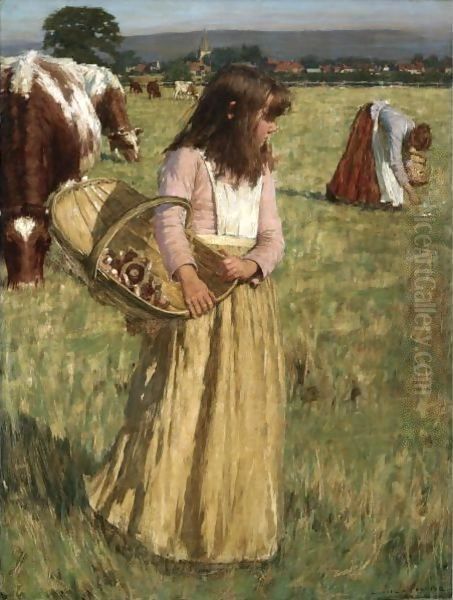

Major Themes and Subjects

The dominant theme throughout La Thangue's oeuvre is rural life. He possessed a deep and abiding interest in the people who worked the land and lived in close connection with nature. His paintings frequently depict agricultural labourers engaged in their tasks: harvesting, ploughing, resting. Works like The Last Furrow and Harvesters Eating portray these activities with dignity and realism, often highlighting the physical demands of rural work. He avoided romanticizing poverty but instead presented an honest, often empathetic view of his subjects.

Beyond agricultural labour, La Thangue explored other facets of country existence. The Village Fountain likely depicted a central point of community life, while Fisherman in Provence shows his interest extended to coastal communities as well. His painting The Mushroom Gatherers (c. 1890s) is a poignant example, depicting children engaged in foraging, touching upon themes of childhood, rural economy, and perhaps the hardships faced by families. These works sometimes carried a subtle social commentary, reflecting contemporary concerns about rural depopulation, poverty, and changing agricultural practices.

Landscape itself was also a crucial subject. Whether depicting the fields and lanes of Norfolk and Sussex in England, or later the sun-drenched environments of Southern Europe, La Thangue showed a remarkable ability to capture the specific character and atmosphere of a place. His landscapes are rarely empty scenes; they are almost always settings for human activity or show the imprint of human presence, reinforcing his focus on the relationship between people and their environment.

Key Works and Exhibitions

La Thangue's reputation was built through regular exhibitions at major venues, primarily the Royal Academy (despite his reformist stance, he continued to exhibit there, becoming an Associate in 1898 and a full Academician in 1912) and the New English Art Club. Several specific works stand out as milestones in his career and exemplify his artistic concerns.

In the Dauphiné (exhibited 1886) is an early, significant work reflecting his time in France. Its subject matter and style were seen as demonstrating his allegiance to French Naturalism and marked him as a proponent of the 'new' painting.

The Return of the Reapers (1886) is another crucial early painting, showcasing his interest in rural labour and his developing technique. Its detailed realism, possibly informed by photography, combined with its focus on ordinary working people, made it a strong statement within the context of British art at the time.

The Last Furrow continued his exploration of agricultural themes, likely depicting the end of a long day's work with characteristic empathy and attention to the effects of light.

The Mushroom Gatherers (c. 1890s) represents his sensitive portrayal of children within the rural landscape, capturing a moment of quiet activity tinged with the realities of rural life.

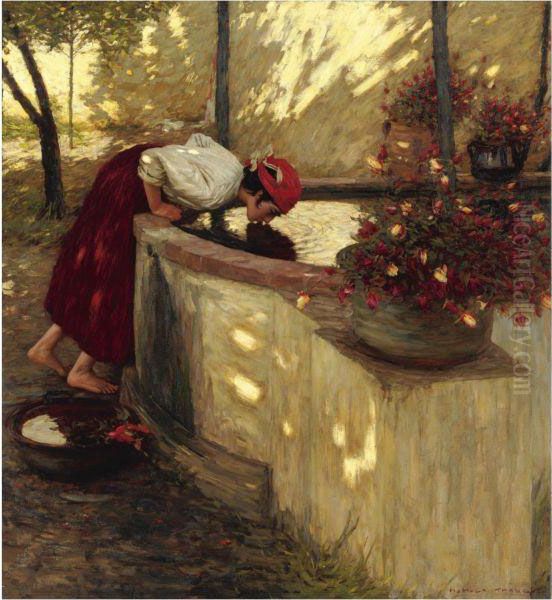

Works from his later period, spent largely in the Mediterranean, such as Ligurian Roses, In a Ligurian Garden, From a Ligurian Spring, and Winter in Liguria, demonstrate a shift towards even brighter light and colour, capturing the intense sunshine and vibrant flora of the region. These paintings often feature figures, particularly women and children, in sunlit gardens or landscapes, blending genre scenes with stunning depictions of light and atmosphere. A Morning Walk (1881, though possibly dated later or a different work with a similar title) suggests his enduring interest in everyday moments within a landscape setting.

Travels and Mediterranean Influence

Around 1901, La Thangue made a significant life change, moving away from England to spend extended periods in Southern Europe. He travelled and worked extensively in Provence in the South of France, Liguria on the Italian Riviera, and also visited the Balearic Islands. This move had a profound impact on his art.

The intense light and vibrant colours of the Mediterranean environment led to a noticeable brightening of his palette and a greater emphasis on capturing the effects of strong sunlight. Subjects shifted towards the characteristic landscapes and activities of these regions: olive groves, vineyards, coastal scenes, sun-drenched gardens filled with flowers. He painted local people, often women engaged in traditional crafts like lace-making in Liguria, or simply enjoying the warmth and light outdoors.

Paintings like Ligurian Roses and Winter in Liguria exemplify this phase. They are characterized by brilliant sunshine, deep shadows often rendered in blues and purples, and the same textured, square-brush application of paint, now used to convey the shimmering heat and dazzling light. While the subject matter changed from the often more sombre agricultural labour of England, his fundamental interest in realism, light, and the human figure within a specific environment remained constant. His time in the Mediterranean solidified his reputation as one of Britain's foremost painters of sunlight.

Later Years and Legacy

Although he spent much of the early 20th century abroad, La Thangue eventually returned to England, settling in the village of Graffham in Sussex. He continued to paint actively in his later years, drawing inspiration from the Sussex countryside while also revisiting themes and memories from his time in the Mediterranean. He remained a respected figure in the British art world, continuing to exhibit his work.

Henry Herbert La Thangue died in London in 1929. He left behind a substantial body of work that occupies an important place in the narrative of British art from the late Victorian era through the early 20th century. His primary legacy lies in his role as a key proponent of rural Naturalism and as one of the leading figures of British Impressionism – a term used somewhat broadly to encompass artists influenced by French plein-air techniques and a focus on light, even if their styles differed from French Impressionists like Monet or Renoir.

He successfully synthesized French influences with a distinctly British sensibility, creating works that were both modern in technique and deeply rooted in the observation of everyday life. His commitment to depicting rural labour with honesty and empathy provides a valuable social document of the era. His distinctive square-brush technique and masterful handling of light continue to be admired. Today, his works are held in major public collections, including the Tate Britain, the National Gallery in London, and numerous regional galleries throughout the UK, ensuring his contribution to art history is preserved and appreciated. His influence can be seen as part of a broader movement towards realism and modernism in British art, alongside contemporaries like George Clausen and Stanhope Forbes, and paving the way for later generations of landscape and figure painters.

Market Recognition

The enduring appeal and artistic significance of Henry Herbert La Thangue's work are reflected in its strong performance on the art market. His paintings are sought after by collectors of British Impressionism and late Victorian art, often commanding high prices at auction.

Specific examples illustrate this market recognition. In 2010, Christie's offered works such as A Morning Walk with an estimate of £100,000-£150,000, and Ligurian Grapes estimated at £200,000-£300,000, indicating significant value. A notable result was achieved in 2007 when From a Ligurian Spring sold for £456,000 (approximately 7,727 at the time), exceeding its pre-sale estimate.

More recently, in 2024, his painting Winter in Liguria achieved an impressive 3,000 at auction, surpassing its estimate of 0,000-0,000. Even works with more modest subjects, like Bracken, carried substantial estimates (£71,100-£89,000 in a 2023 auction preview). These figures demonstrate a consistent and high level of demand for La Thangue's paintings, particularly those from his desirable Mediterranean period, confirming his status as a major name in his field whose work continues to resonate with collectors and art enthusiasts.

Conclusion

Henry Herbert La Thangue carved a unique path through the complex art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Educated in the academic traditions of London and Paris, he embraced the progressive influences of French Naturalism and plein-air painting, forging a distinctive style characterized by bold brushwork, luminous colour, and a profound engagement with rural life. Whether depicting the toil of English farmworkers or the sunlit leisure of the Mediterranean, his work consistently reveals a deep sensitivity to light, atmosphere, and the human condition. As a founding influence on the New English Art Club and a respected member of the Royal Academy, he played a role in shaping the direction of British art. His legacy endures through his captivating paintings, which continue to be celebrated for their technical brilliance, emotional honesty, and timeless depiction of life lived in harmony and struggle with the natural world.