Frederick Ferdinand Schafer stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the grand tradition of nineteenth-century American landscape painting. A prolific artist whose career bridged the artistic sensibilities of his native Germany and the burgeoning identity of the American West, Schafer dedicated his talents to capturing the dramatic vistas and unique atmosphere of a rapidly changing frontier. His canvases offer viewers a window into the mountains, forests, and waterways of California and the Pacific Northwest as they appeared during a pivotal era of exploration and settlement.

Born in Brunswick, Germany, on August 16, 1839, Schafer's early life and artistic training remain somewhat sparsely documented, adding a layer of intrigue to his biography. However, evidence suggests he may have received formal art instruction in Düsseldorf, a major center for landscape painting in Germany. The Düsseldorf Academy was renowned for its detailed, often romanticized, approach to nature, an influence that can be subtly detected in Schafer's later work, particularly in his meticulous rendering of natural forms and his sensitivity to atmospheric effects.

The pivotal moment in Schafer's life and career came in 1876, when, at the age of 37, he immigrated to the United States. He settled initially in San Francisco, a city buzzing with energy and serving as a gateway to the vast, awe-inspiring landscapes of the American West. This move placed him directly into a thriving, competitive art scene and provided him with the subject matter that would define his artistic legacy: the untamed wilderness of the western territories.

Forging an Artistic Identity in the West

Upon arriving in America, Schafer entered a landscape art tradition already being powerfully shaped by painters associated with the Hudson River School, such as Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Edwin Church. While Schafer likely absorbed influences from these East Coast masters, known for their monumental canvases and sometimes highly dramatized depictions of nature, his own path diverged. He established his primary studios not on the East Coast, but in San Francisco and later Oakland, California, immersing himself in the specific light and topography of the Pacific region.

The San Francisco Bay Area in the 1870s and 1880s was a hub for artists drawn to the West's scenic wonders. Schafer became part of this vibrant community, exhibiting his work alongside contemporaries and developing a style that resonated with the prevailing taste for Romantic Realism. His approach shared affinities with fellow California artists like Thomas Hill and William Keith, who also specialized in capturing the grandeur of the Sierra Nevada and other Western landmarks.

Schafer’s style, however, retained a distinct character. While clearly rooted in the realistic depiction of nature, he often employed techniques to heighten the emotional impact of his scenes. He was less concerned with photographic precision than with conveying the overall impression and mood of a place. This sometimes involved a more painterly application of pigment and a focus on the interplay of light and shadow to create atmosphere, a quality that also connects him to artists like Ransom Gillet Holdredge and Juan Buckingham Wandesford, whose works sometimes shared a similar tonal sensitivity prevalent in the San Francisco school.

A Signature Style: Light, Color, and Atmosphere

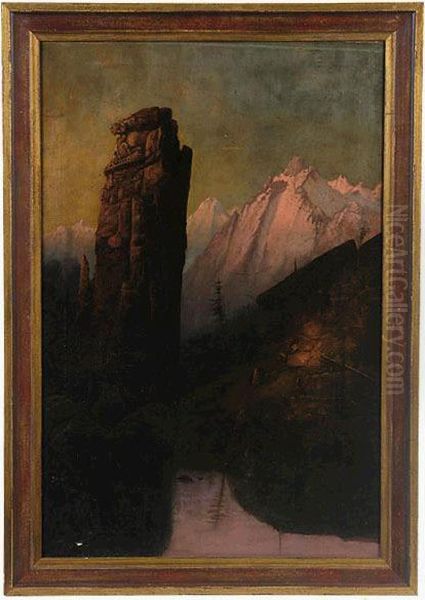

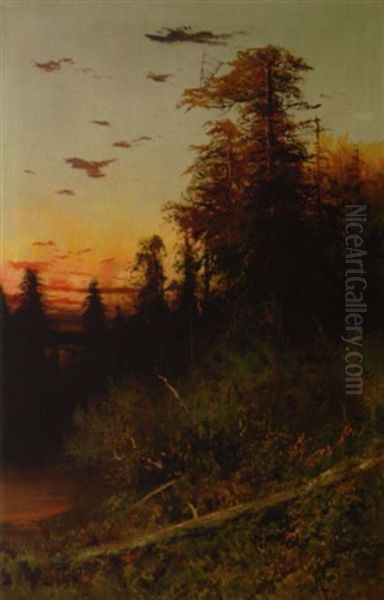

Frederick Schafer's paintings are immediately recognizable for their distinctive handling of light and color. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the varied atmospheric conditions of the West, from the crisp, clear air of the high mountains to the soft, diffused light of coastal fog or the dramatic glow of a sunset. His palettes often feature strong contrasts, juxtaposing the deep shadows of a forest interior with brightly lit clearings or snow-capped peaks, or the cool blues and greens of water against the warm earth tones of rocks and soil.

Light is paramount in Schafer's work. He masterfully depicted the way sunlight filters through trees, strikes the face of a cliff, or reflects off the surface of a lake or river. His sunsets are particularly noteworthy, often rendered with saturated hues of orange, pink, and gold that convey both the beauty and the ephemeral nature of the day's end. These effects, while dramatic, generally avoid the operatic intensity found in the most famous works of Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, grounding his scenes in a more observable reality.

Schafer's treatment of space also contributes significantly to the impact of his paintings. He often constructed his compositions with planes parallel to the picture surface, leading the viewer's eye deep into the scene. In his forest interiors, dense trees might fill the canvas, obscuring the horizon entirely and creating an immersive, almost claustrophobic sense of enclosure within the woods. Conversely, his mountain vistas often emphasize vast distances, using atmospheric perspective to render distant peaks in soft, hazy tones, enhancing the feeling of immense scale.

Water is another element Schafer rendered with particular skill. Rivers flow convincingly, waterfalls cascade with energy, and the still surfaces of lakes offer believable, often subtly blurred, reflections of the surrounding landscape. This facility with depicting water in its various forms adds dynamism and realism to his compositions, whether portraying the tranquil Merced River in Yosemite or the rugged coastline of the Pacific.

The Human Element in Vast Landscapes

While Schafer's primary subject was the landscape itself, his paintings frequently include small figures that serve multiple purposes. Often, these are Native Americans, depicted singly or in small groups, sometimes near encampments suggested by tipis and campfires. Other times, pioneers, hunters, prospectors, or even animals like deer or bears populate the scenes. These figures are almost invariably small in scale, positioned in the middle ground or distance.

This deliberate scaling emphasizes the overwhelming majesty and vastness of the natural environment. The human presence appears diminutive, even fragile, against the backdrop of towering mountains, immense forests, or expansive plains. This compositional strategy underscores a common theme in nineteenth-century landscape painting: the relationship between humanity and nature, often highlighting nature's power and indifference to human endeavors.

These small figures also add narrative interest and focal points to the compositions. A tiny campfire glowing in the twilight, a lone rider traversing a mountain pass, or a Native American fishing by a stream invites the viewer to imagine the stories unfolding within the scene. These elements, often rendered as small, bright accents of color – a red blanket, the orange flicker of a fire – draw the eye and add touches of warmth or intrigue to the otherwise wild landscapes.

Depicting the Untamed Wilderness

Schafer's work is particularly valuable for its depiction of the American West before widespread development transformed the landscape. He seemed especially drawn to portraying the wild, unmanaged character of the region's forests. Unlike the often manicured woodlands of Europe, Schafer's painted forests frequently feature fallen logs, dense undergrowth, and a sense of untamed, primordial nature. This fidelity to the specific character of the American wilderness distinguishes his work.

His subjects spanned a wide geographical range across the West. He painted numerous scenes in California, including iconic locations like Yosemite Valley, the Sierra Nevada mountains, Mount Shasta, and the coastal regions. His travels also took him to Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Montana, and possibly Utah and British Columbia, allowing him to capture the diverse scenery of the Pacific Northwest and the Rocky Mountains.

Whether depicting the granite cliffs of Yosemite, the volcanic cone of Mount Shasta rising above forested slopes, a tranquil mountain lake, or a desert landscape under a vast sky, Schafer consistently sought to convey the unique character and mood of each location. His paintings document not only the topography but also the changing seasons and times of day, capturing the West in its myriad aspects.

Key Subjects and Representative Works

Throughout his prolific career, estimated to encompass over 500 paintings, certain subjects recurred frequently in Schafer's oeuvre. Yosemite Valley was a clear favorite, with numerous canvases dedicated to its famous waterfalls, granite domes, and the Merced River winding through the valley floor. Mount Shasta, with its imposing, often snow-covered peak, was another signature subject, depicted from various vantage points and under different lighting conditions.

Scenes featuring Native American life were common, typically portraying small encampments nestled within grand landscapes, often at dawn or dusk, imbued with a sense of quietude or mystery. Twilight and sunset scenes, regardless of location, allowed Schafer to explore his fascination with dramatic light and color effects. Forest interiors, coastal views, and expansive mountain panoramas rounded out his primary thematic interests.

While many of his works reside in private collections, notable examples can be found in public institutions. A painting titled Mountain Landscape, dated between 1875 and 1900 and housed at the Fairfield University Art Museum, exemplifies his typical approach, harmoniously combining elements of land, mountains, sky, trees, and water. Another significant work, depicting Mount Shasta, is associated with the San Francisco Art Association. The Alameda Free Library in California holds an 1880s Schafer landscape, donated in 1894 by a family connected to the Southern Pacific Railroad, highlighting the contemporary appreciation for his work.

Exhibitions and Recognition in His Time

Frederick Schafer actively participated in the art world of his adopted home. He regularly submitted his paintings to exhibitions held by the San Francisco Art Association, a prestigious organization that played a crucial role in the city's cultural life. His work was also featured at the popular Mechanics' Institute Fairs in San Francisco, large public expositions that included art displays and helped artists reach a broader audience.

His participation in these venues indicates that he achieved a degree of recognition and acceptance within the competitive California art market. While perhaps not reaching the national fame of Bierstadt or Moran, whose monumental works toured the country, Schafer was a respected and productive member of the West Coast art community. His style, blending German training with American subjects and a sensitivity to the specific qualities of Western light and landscape, found favor with local patrons and collectors.

The economic context of the late nineteenth century, including periods of financial panic, undoubtedly impacted the art market and artists like Schafer. However, his consistent production over several decades suggests he was able to sustain a professional career as a landscape painter, finding buyers for his evocative depictions of the West.

Schafer and His Contemporaries: Comparisons and Context

Placing Schafer within the broader context of nineteenth-century American art reveals both connections and distinctions. His potential Düsseldorf training links him to other German-American artists who made significant contributions to landscape painting, such as Hermann Herzog, who also painted Western scenes, and Worthington Whittredge, though Whittredge is more associated with the Hudson River School's eastern subjects.

Compared to the epic scale and sometimes theatrical drama of Bierstadt and Moran, Schafer's work often feels more intimate and atmospheric, even when depicting grand vistas. While he employed strong light and color, his realism generally kept him from the more overt romanticism or sublime terror found in some canvases by Church or Bierstadt. His focus remained steadfastly on the landscape itself, rendered with sensitivity and a keen eye for natural effects.

Within the California school, his work sits alongside that of Thomas Hill and William Keith, both highly successful painters of Yosemite and the Sierras. While sharing subject matter, Schafer's technique often differed, perhaps showing a slightly looser brushwork or a greater emphasis on mood over precise detail compared to Hill's sometimes tighter rendering. He also seems distinct from California artists focused on still life, like Samuel Marsden Brookes, or those specializing in tropical scenes, like Norton Bush, or genre painting, like Carl Wilhelm Hahn. Schafer remained dedicatedly a landscape specialist.

His relationship with artists like Holdredge and Wandesford points to the shared stylistic currents within the San Francisco art scene of the period – a tendency towards tonalism and atmospheric representation that coexisted with the more detailed realism favored by others. Schafer navigated these trends, developing a personal style that blended careful observation with expressive handling of light and color.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

Frederick Ferdinand Schafer continued to paint actively into the early twentieth century, with his main body of work dating from the mid-1870s to around 1911. He spent his later years primarily in the San Francisco Bay Area, maintaining a studio in Oakland for a significant period. He passed away in Oakland, California, on July 18, 1927, at the age of 87.

His legacy rests on the substantial body of work he produced, offering a comprehensive visual record of the American West during a transformative period. While overshadowed in popular recognition by a few contemporaries who achieved international fame, Schafer's paintings hold significant historical and artistic value. They capture the unique atmosphere, light, and untamed character of Western landscapes with a distinctive blend of realism and romantic sensibility.

For collectors of Western American art and regional art history enthusiasts, Schafer remains an important figure. His works document specific locations, reflect the artistic tastes of the era, and showcase a personal vision honed over decades of observing and painting the diverse scenery of California and the Pacific Northwest. The relative scarcity of detailed biographical information only adds to the quiet allure of this dedicated chronicler of the West.

Collections and Market Presence

Today, works by Frederick Ferdinand Schafer are held in various public and private collections. Key institutional holdings include the Oakland Museum of California, which has a strong collection of California art, the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, and the previously mentioned Alameda Free Library and Fairfield University Art Museum. His connection with the San Francisco Art Association also suggests potential holdings related to that institution's historical collections.

While detailed, comprehensive auction records were not readily available in the source material consulted, Schafer's paintings regularly appear on the art market. They are offered through galleries specializing in historical American art and appear at auctions featuring Western or Californian painting. The value of his works varies depending on size, subject matter, condition, and provenance, but his consistent market presence confirms an ongoing appreciation for his contribution to American landscape art.

His depictions of iconic locations like Yosemite and Mount Shasta, as well as scenes featuring Native Americans, tend to be particularly sought after. The enduring appeal of his work lies in its ability to transport viewers to the nineteenth-century West, offering glimpses of its natural splendor through the eyes of a skilled and sensitive artist.

Conclusion: A Vision of the Untamed West

Frederick Ferdinand Schafer carved a unique niche for himself within the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century American landscape painting. As a German immigrant who embraced the American West as his primary subject, he brought a distinct perspective, possibly shaped by his European training, to the depiction of New World scenery. His prolific output, characterized by dramatic yet believable light and color, atmospheric sensitivity, and a focus on the untamed aspects of the wilderness, provides a valuable and evocative record of California and the Pacific Northwest during an era of profound change.

Though perhaps not as widely celebrated as some of his contemporaries, Schafer's contribution is significant. His paintings offer more than just topographical records; they convey a sense of mood, place, and the overwhelming power of nature, often subtly contrasted with the small scale of human presence. Through his consistent dedication and distinct artistic vision, Frederick Ferdinand Schafer secured his place as an important chronicler of the majestic, luminous, and untamed landscapes of the American West.