Introduction: An Artist Bridging Continents and Styles

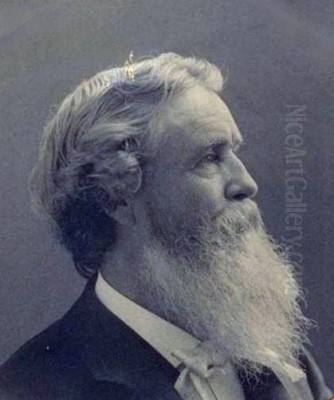

Thomas Hill stands as a significant figure in the pantheon of 19th-century American landscape painters. Born in Birmingham, England, on September 11, 1829, his life and art traversed the Atlantic, ultimately finding their most profound expression in the monumental landscapes of the American West. Migrating to the United States with his family at the age of 15, Hill embarked on an artistic journey that would see him become closely associated with the later generation of the Hudson River School, yet carve out a distinct identity through his breathtaking depictions of California's Sierra Nevada, particularly the Yosemite Valley, and the rugged beauty of New Hampshire's White Mountains. His work captured the romantic spirit of the age, celebrating the sublime power and seemingly eternal grandeur of nature, resonating deeply with a nation forging its identity against the backdrop of vast, untamed wilderness. Hill's legacy is that of an artist who not only documented iconic American vistas but also imbued them with a sense of awe and wonder.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Hill's formative years provided a foundation for his later artistic pursuits. After arriving in the United States around 1844, the family settled initially in the Northeast. His early professional life saw him working in Taunton, Massachusetts, engaged in the practical craft of carriage painting. This experience, while seemingly distant from fine art, likely honed his skills in handling pigments and executing detailed work. However, the allure of landscape painting soon took hold, prompting a shift in his career trajectory.

Seeking formal training, Hill enrolled at the prestigious Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in Philadelphia. There, he studied under the tutelage of Peter Frederick Rothermel, a noted American painter known primarily for his historical scenes and portraits. Rothermel's instruction would have provided Hill with a solid grounding in academic drawing and painting techniques. This period was crucial in transitioning Hill from a decorative painter to a fine artist, equipping him with the technical proficiency needed to tackle the complexities of landscape representation. His time at PAFA exposed him to the burgeoning American art scene and likely solidified his commitment to capturing the natural world on canvas.

The Hudson River School Influence

Thomas Hill's artistic development occurred during the flourishing of the Hudson River School, America's first true school of landscape painting. While perhaps not a core member in the same vein as its founders, Hill was deeply influenced by the movement's aesthetic and philosophical principles. The Hudson River School artists, including pioneers like Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand, sought to portray the American landscape not just as picturesque scenery, but as a manifestation of divine power and a source of national pride. They emphasized detailed observation, dramatic compositions, and often imbued their works with a moral or spiritual dimension.

Hill absorbed these ideals, particularly the emphasis on capturing the sublime – the feeling of awe mixed with a sense of delightful terror evoked by vast, powerful natural phenomena. His work shares affinities with second-generation Hudson River School painters such as Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, who expanded the movement's scope to encompass the more dramatic landscapes of South America and the American West. Hill, like Bierstadt, became renowned for his large-scale canvases depicting majestic mountain ranges and breathtaking vistas, rendered with meticulous attention to detail and often bathed in dramatic, atmospheric light. This connection places Hill firmly within the broader narrative of 19th-century American romantic landscape painting.

The White Mountains Period

Before achieving fame for his Western scenes, Thomas Hill spent considerable time exploring and painting the White Mountains of New Hampshire. This region was a popular destination for artists associated with the Hudson River School, offering rugged peaks, dense forests, and picturesque valleys. During the 1850s and early 1860s, Hill made numerous sketching trips to the area, often in the company of fellow artists.

One significant collaborator during this period was Benjamin Champney, another prominent White Mountain painter. Together, they would venture into the wilderness, making plein air sketches that would later serve as studies for larger studio compositions. This practice of direct observation was fundamental to the Hudson River School ethos, championed by figures like Asher B. Durand in his "Letters on Landscape Painting." Hill's experiences in the White Mountains honed his skills in capturing the specific atmospheric conditions and geological features of mountainous terrain. Works from this era, such as the notable Mount Lafayette in Winter, demonstrate his growing mastery of landscape composition and his ability to convey the stark beauty and challenging environment of the New England wilderness, establishing his reputation as a capable landscape artist even before his move west. Other artists drawn to this region included Jasper Francis Cropsey and Sanford Robinson Gifford, contributing to a rich artistic tradition centered on these mountains.

The Call of the West: California Bound

The trajectory of Thomas Hill's career took a decisive turn in the early 1860s (sources vary slightly, often citing 1861 or his presence there by 1856, settling more permanently later) when he moved to California, settling in San Francisco. The burgeoning state, flush with Gold Rush wealth and brimming with dramatic, largely unpainted landscapes, offered immense opportunities for an ambitious artist. San Francisco was rapidly becoming a cultural center, and Hill quickly established himself within its growing art community.

The move West proved transformative. The scale and character of the Californian landscape, particularly the Sierra Nevada mountains and the Yosemite Valley, were unlike anything he had encountered on the East Coast. These monumental scenes perfectly suited his inclination towards the grand and the sublime, providing subjects that would define the remainder of his career. It was in California that Hill found the landscapes that would become synonymous with his name, allowing him to create the large-scale, panoramic canvases for which he is best known. His arrival coincided with a growing national fascination with the West, fueled by exploration reports, photographs, and early artistic depictions.

Collaboration and Documentation: Watkins and Yosemite

Upon arriving in California, Hill's exploration of the state's natural wonders was significantly aided by his association with the pioneering photographer Carleton Watkins. Watkins was already making groundbreaking photographic expeditions into the Yosemite Valley, producing stunning large-format images that captured the public imagination and played a role in the eventual preservation of the area.

Hill accompanied Watkins on several trips to Yosemite, beginning as early as 1862. This collaboration was mutually beneficial. Watkins' photographs provided detailed visual records that Hill could reference in his studio work, while Hill's paintings offered a dimension of color, atmosphere, and artistic interpretation that photography at the time could not fully convey. Traveling and working alongside Watkins allowed Hill intimate access to Yosemite's most iconic viewpoints and fostered a deep connection with the valley's unique geology and atmosphere. These early visits were crucial in establishing Yosemite as a central theme in Hill's oeuvre, leading to numerous sketches and paintings that helped solidify both his and the valley's fame.

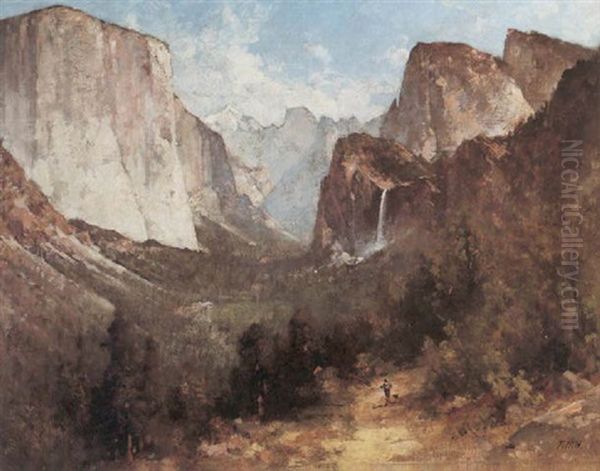

Yosemite: The Defining Subject

While Hill painted various landscapes throughout his career, the Yosemite Valley became his most enduring and iconic subject. He returned to the valley repeatedly over several decades, drawn by its unparalleled concentration of natural wonders: the sheer granite cliffs of El Capitan and Half Dome, the delicate cascades of Bridalveil and Vernal Falls, the towering Giant Sequoias of the Mariposa Grove, and the tranquil Merced River winding through the valley floor.

Hill's Yosemite paintings range from intimate studies of specific features to vast, panoramic canvases encompassing the entire valley. Works like Yosemite Valley (numerous versions exist, including a famous one from 1887) and Vernal Falls are considered among his masterpieces. He captured the valley in different seasons and varying light conditions, showcasing its dramatic moods and sublime beauty. His depictions often emphasized the immense scale of the landscape, sometimes including small human figures to accentuate the towering cliffs and waterfalls, a common trope in Romantic landscape painting used to evoke feelings of awe and human insignificance before the power of nature. His dedication to this subject was so profound that in 1873, he built a studio gallery in Wawona, near the southern entrance to the park, allowing him to work on-site and cater to the growing tourist trade interested in his depictions of the famous valley. This studio later became a community center.

Artistic Style and Technique

Thomas Hill's style evolved throughout his career but remained rooted in the traditions of Romanticism and the Hudson River School. His work is characterized by a commitment to topographical accuracy combined with a heightened sense of drama and grandeur. He excelled at creating panoramic compositions that offered sweeping views of expansive landscapes, meticulously rendering geological details, foliage, and atmospheric effects.

His use of light was often dramatic, employing strong contrasts between illuminated peaks and shadowed valleys to enhance the sense of depth and monumentality, reminiscent of the Luminist tendencies within the Hudson River School, although perhaps less focused on tranquility and more on grandeur. His color palette was rich and varied, capable of capturing both the vibrant hues of a California sunset and the cool tones of a snow-capped mountain. While influenced by European landscape traditions, particularly the Barbizon School's emphasis on looser brushwork in his earlier pieces, his mature style, especially in his large Western canvases, prioritized detailed realism combined with idealized compositions. He aimed not just to record a scene but to convey the emotional impact of experiencing such majestic nature, aligning with the ideas of theorists like John Ruskin who advocated for "truth to nature."

Major Works and Commissions

Beyond his numerous Yosemite scenes, Thomas Hill produced several other significant works that cemented his reputation. One of the most famous is The Last Spike, painted in 1881. This large historical landscape commemorates the joining of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads at Promontory Summit, Utah, in 1869, an event that symbolically and physically united the nation. While commissioned years after the event by Leland Stanford (who was dissatisfied with the original, more documentary painting by A.J. Russell), Hill's version is a grand, somewhat idealized depiction featuring portraits of key figures involved in the railroad's construction, set against a dramatic landscape backdrop.

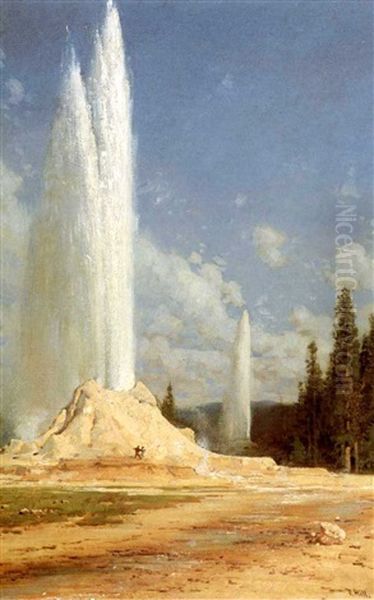

Another important commission came from the famed naturalist and conservationist John Muir. Muir, a passionate advocate for wilderness preservation, asked Hill to paint the Muir Glacier in Alaska. Hill undertook the journey and produced a stunning depiction of the massive tidewater glacier, capturing its icy grandeur and scale. This painting, now housed in the Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center, stands as a testament to Hill's willingness to travel to remote locations to capture extraordinary natural phenomena and his connection to the burgeoning conservation movement through figures like Muir. Other notable works include Great Canon of the Sierra and Yellowstone Geysers, showcasing his versatility in depicting different types of dramatic Western landscapes.

Artistic Circles: Collaborators and Contemporaries

Thomas Hill was an active participant in the art scenes of both the East and West Coasts. His early collaborations in the White Mountains with Benjamin Champney have already been noted. In California, his association with Carleton Watkins was pivotal. He also traveled and painted with other artists, including Virgil Williams, who became the first director of the California School of Design (later the San Francisco Art Institute).

Hill's success inevitably placed him in comparison, and sometimes competition, with other prominent landscape painters of the era. His most significant contemporary in depicting the grand landscapes of the West was Albert Bierstadt. Both artists created large, dramatic, and highly detailed canvases of Yosemite, the Rockies, and other Western landmarks, often competing for patronage and public acclaim. While their styles shared similarities, Bierstadt often employed a more overtly theatrical and sometimes exaggerated approach, influenced by the Düsseldorf school, whereas Hill, while still dramatic, often maintained a slightly more grounded naturalism. Hill was also a contemporary of other California artists like William Keith, known for his more Tonalist and Barbizon-influenced landscapes, and Charles Christian Nahl, known more for historical and genre scenes but also part of the San Francisco art milieu. Hill's brother, Edward Hill, was also a landscape painter, though he never achieved the same level of fame.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Associations

Throughout his career, Thomas Hill actively exhibited his work and gained significant recognition. His exhibition history began relatively early, with a showing of thirty oil paintings in Boston in 1858. He exhibited at the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York, showing a Yosemite scene in 1865. That same year, his work gained international exposure at the Paris Exposition Universelle.

In California, he quickly became a leading figure. He won an award from the Art Union of San Francisco in 1865. His national reputation was further solidified when he received awards at the important Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876, celebrating the nation's 100th anniversary. He also received a medal from his alma mater, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, during an exhibition in 1884. Demonstrating his commitment to the local art community, Hill was a key figure in the founding of the San Francisco Art Association in 1871 and served as its interim director for a period, contributing significantly to the institutional development of art in California. His painting View of the Yosemite Valley received renewed attention when it was chosen as the backdrop for President Barack Obama's inaugural luncheon in 2009, commemorating Abraham Lincoln's signing of the Yosemite Grant.

Later Career, Legacy, and Reappraisal

Thomas Hill enjoyed considerable success and popularity during the 1870s and 1880s, becoming one of California's most celebrated and financially successful artists. His large canvases commanded high prices, and his Wawona studio became a popular stop for affluent tourists visiting Yosemite. However, towards the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, artistic tastes began to shift. The rise of Impressionism, Tonalism, and other modern art movements led to a decline in the popularity of the detailed, panoramic style of the Hudson River School and artists like Hill and Bierstadt.

Consequently, Hill's work, once highly sought after, fell somewhat out of favor and was considered old-fashioned by proponents of newer styles. Despite this shift in taste, he continued to paint, primarily based near Yosemite, until his death in Raymond, California, on June 30, 1908, at the age of 79. For much of the 20th century, his work was relatively overlooked by mainstream art history. However, beginning in the latter half of the century, there was a significant reappraisal of 19th-century American art. Scholars and curators began to re-evaluate the contributions of the Hudson River School and related artists.

Today, Thomas Hill is recognized as a major figure in American landscape painting. His works are held in numerous prestigious museum collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (de Young and Legion of Honor), the Oakland Museum of California, and many others. His paintings are admired for their technical skill, their historical significance as documents of the American West, and their powerful evocation of the sublime beauty of nature. His Wawona studio remains a historic landmark within Yosemite National Park.

Conclusion: Capturing the American Sublime

Thomas Hill's artistic journey mirrors the expansionist spirit and evolving identity of 19th-century America. From his beginnings in industrial England to his immersion in the wilderness of New England and finally his career-defining encounters with the monumental landscapes of the American West, Hill dedicated his life to capturing the grandeur of the natural world. As a prominent figure associated with the later Hudson River School, he skillfully blended detailed realism with Romantic sensibility, creating canvases that conveyed both the specific character of place and a universal sense of awe.

His depictions of the Yosemite Valley, in particular, remain iconic representations of one of America's most cherished natural treasures. Through his prolific output, numerous exhibitions, and active participation in the art community, Hill played a vital role in shaping the visual culture of California and contributing to the broader tradition of American landscape painting. Though his style fell out of fashion for a time, the enduring power and beauty of his work have ensured his place as a significant chronicler of the American sublime, whose paintings continue to inspire appreciation for the nation's natural heritage.