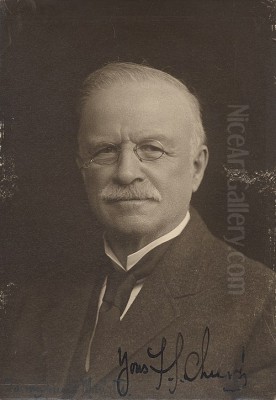

Frederick Stuart Church (1842-1924) stands as a unique figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century American art. Primarily celebrated for his enchanting illustrations and paintings, often featuring animals imbued with human-like qualities and characteristics, Church carved a niche for himself that blended technical skill with a distinctive, imaginative vision. His work, appearing in popular magazines, books, and galleries, brought a sense of gentle humor, romanticism, and allegory to a wide audience. Born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, and living through a period of significant transformation in American society and art, Church's journey from a potential businessman to a beloved artist is a fascinating tale of talent finding its true course.

Early Life and a Path Diverged

Frederick Stuart Church was born in Grand Rapids, Michigan, on December 1, 1842. His family background was rooted in prominence; his father was a respected lawyer and politician, and his mother, Mary Elizabeth Stuart, hailed from a notable family. The expectation, it seems, was for young Frederick to follow a path into the world of commerce, a common aspiration for sons of successful families during that era.

Evidence of his artistic inclinations emerged early, but practicality initially won out. At the young age of thirteen, Church left formal schooling behind and took up a position with the American Express Company in Chicago, which was then a rapidly growing hub of commerce and industry. This early foray into the business world, however, proved to be a detour rather than a destination. The stirrings of artistic ambition and the dramatic interruption of national conflict would soon redirect his life entirely.

The Crucible of War

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 fundamentally altered the trajectory of Church's life, as it did for countless young men of his generation. At nineteen, despite the expectations perhaps held by his family for a business career, Church enlisted in the Union Army. He joined the Chicago Light Artillery, Battery A. His military service was not without incident; sources recount a period of confinement lasting 35 days, reportedly due to his refusal to serve as an infantryman after his artillery unit faced challenges.

This wartime experience, though undoubtedly difficult, seems to have solidified his resolve. The discipline, the exposure to the wider world, and perhaps the confrontation with mortality may have clarified his priorities. Upon the conclusion of the war, Church returned not to the ledgers of American Express, but to the studios of Chicago, determined now to dedicate his life fully to the pursuit of art. This decision marked the true beginning of his artistic journey.

Forging an Artist in Chicago and New York

Back in Chicago after the war, Church began his formal art training in earnest. He enrolled at the Chicago Academy of Design (a precursor to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago). There, he studied under Walter Shirlaw (1838-1909), a respected painter and etcher who would become an influential figure in American art education. Shirlaw's guidance provided Church with a foundational understanding of drawing and painting techniques.

Seeking broader opportunities and more advanced instruction, Church made the pivotal move to New York City around 1870. This relocation placed him at the epicenter of the American art world. He continued his studies at the prestigious National Academy of Design, a bastion of traditional art education. His instructor there was Lemuel Everett Wilmarth (1835-1918), another significant figure associated with the Academy and later with the Art Students League. Wilmarth's teaching likely focused on academic principles, including drawing from casts and life models.

Church also became deeply involved with the Art Students League of New York. Founded in 1875 partly as a reaction against the perceived conservatism of the National Academy, the League offered a more liberal and student-driven environment. Notably, Walter Shirlaw was a key figure in the League's early years, serving as one of its first instructors and presidents. Church maintained a lifelong affiliation with the League, finding a community and an educational home that supported his developing style.

The Illustrator's Eye

While pursuing painting, Frederick Stuart Church rapidly gained recognition as a gifted illustrator. This was the "Golden Age of American Illustration," a period when magazines like Harper's Weekly, Scribner's Monthly, and The Century Magazine flourished, employing talented artists to bring stories and articles to life. Church's unique sensibility, particularly his charming and often humorous depictions of animals, found a ready market.

His illustrations graced the pages and sometimes the covers of these prominent publications, making his work widely accessible to the American public. He developed a reputation for his imaginative compositions and his ability to convey narrative and emotion through his drawings. His skill was not limited to periodicals; he also illustrated books. A notable collaboration involved providing illustrations, alongside the painter and etcher Robert Swain Gifford (1840-1905), for editions of Edgar Allan Poe's works. This project was significant, reportedly influencing how readers visualized and appreciated Poe's famously atmospheric and often dark writings.

Church's success as an illustrator was built on his keen observational skills, honed by studying animals at zoos and circuses, and his dedication to understanding anatomy. This foundation allowed him to depict animals realistically, even when placing them in fantastical or anthropomorphic scenarios. His work stood out for its blend of technical proficiency and imaginative flair, appealing to both adults and children. He even penned his own stories, such as "The White Tiger," further showcasing his narrative talents.

Master of Whimsy: Animals and Anthropomorphism

The defining characteristic of Frederick Stuart Church's art is undoubtedly his fascination with animals, often portrayed with human-like expressions and engaged in whimsical activities. Bears, tigers, flamingos, rabbits, and other creatures populate his canvases and illustrations, frequently interacting with elegant, idealized female figures or acting out charming allegories on their own.

This wasn't mere cartooning; Church possessed a deep understanding of animal anatomy and movement, which lent credibility to his imaginative scenes. He didn't just draw animals; he seemed to understand their character, infusing them with personality and emotion. A bear might be depicted contemplating love, owls might appear scholarly, or flamingos might engage in a graceful dance. This anthropomorphism was gentle and humorous, rarely satirical in a biting way, distinguishing his work from artists like William Holbrook Beard (1824-1900), another American painter known for satirical animal scenes.

Church's approach often carried symbolic weight. Animals could represent aspects of human nature, comment on social mores, or simply exist in harmonious, dreamlike settings that evoked a sense of peace and beauty. His frequent pairing of graceful women with wild animals suggested a romanticized vision of nature, where innocence and wildness could coexist peacefully. This focus on charming, often narrative scenes featuring animals became his signature, beloved by collectors and the public alike.

The Etcher's Touch

Beyond painting and illustration, Frederick Stuart Church was also an accomplished etcher. He embraced this medium during a period known as the American Etching Revival, which gained momentum in the 1870s and 1880s. Etching, with its potential for fine lines, rich tonal variations, and intimate scale, appealed to artists seeking alternatives to large-scale academic painting and the reproductive demands of commercial illustration.

Church studied etching techniques and quickly mastered the craft. His skill was recognized by his peers, leading to his election as a member of the influential New York Etching Club. This organization played a crucial role in promoting etching as a fine art form in America, holding exhibitions and publishing portfolios. Church's etchings often explored the same themes found in his paintings and illustrations – whimsical animals, allegorical scenes, and graceful figures.

His participation in the Etching Revival placed him alongside other prominent American artists exploring the medium, such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) (though primarily based in Europe), Thomas Moran (1837-1926), Mary Nimmo Moran (1842-1899), Stephen Parrish (1846-1938), and his former collaborator Robert Swain Gifford. Church's etchings were highly regarded, sought after by collectors, and even commissioned by prestigious international publications like the Parisian journal L'Art, demonstrating the reach of his reputation.

Style and Influences: Romanticism, Symbolism, and Individuality

Frederick Stuart Church's artistic style is often characterized as Romantic, though it incorporates elements that align with Symbolism and the broader Aesthetic Movement of the late 19th century. His work consistently emphasizes emotion, imagination, and beauty over strict realism or social commentary. The influence of his teacher, Walter Shirlaw, known for his decorative sensibilities, can perhaps be seen in Church's fluid lines and harmonious compositions.

A key feature of his style is the delicate handling of light and atmosphere. He often employed soft, diffused light or subtle chiaroscuro to create a dreamlike or idyllic mood. His color palette tended towards harmonious tones, enhancing the gentle, often lyrical quality of his scenes. While grounded in careful observation, particularly of animals, his work transcends mere representation, aiming instead for evocation and suggestion.

Church's focus on idealized female figures, often depicted in flowing robes and interacting serenely with nature or animals, connects him to Aesthetic Movement ideals, which prioritized "art for art's sake" and the pursuit of beauty. While not explicitly part of a Symbolist group, the allegorical nature of many of his works, where animals and scenes carry deeper meanings, resonates with Symbolist tendencies seen in contemporaries like Albert Pinkham Ryder (1847-1917), albeit with a much lighter and less mystical tone.

He remained somewhat independent of the major stylistic shifts occurring during his career, such as the rise of American Impressionism championed by artists like Childe Hassam (1859-1935) or John Henry Twachtman (1853-1902). Church maintained his unique focus on narrative, whimsy, and a romanticized view of the natural world, creating a distinctive and personal artistic language.

Notable Works and Themes

Throughout his long career, Frederick Stuart Church created a significant body of work across painting, illustration, and etching. Several pieces stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. A Symphony, Nineteenth Century and The Viking's Daughter are often cited, showcasing his interest in allegorical themes, idealized female figures, and a sense of harmony or narrative drama within a romanticized setting.

Other notable works further illustrate his range and signature subjects:

The Lion in Love: A classic example of his anthropomorphic animal themes, likely depicting the fable with gentle humor.

Pandora: Featuring a typical Church female figure, likely exploring the mythological theme with his characteristic grace and perhaps a touch of playful curiosity rather than impending doom.

Flamingo Duet or similar flamingo paintings: Church was particularly fond of depicting these elegant birds, often in graceful, dance-like compositions that highlight their form and color.

Knowledge is Power: Often depicting owls or other creatures associated with wisdom, showcasing his allegorical inclinations.

Illustrations for Joel Chandler Harris's Uncle Remus: While specific verification can be complex, Church's style was well-suited to animal-centric folk tales, and he was active during the period these stories gained immense popularity. His known skill with animal illustration makes such commissions plausible and aligns with his oeuvre.

Recurring themes in his work include the harmony between humanity (represented by idealized women) and the animal kingdom, the gentle power of nature, the beauty of innocence, and allegorical explorations of love, wisdom, and music. His art consistently offers an escape into a world more beautiful, harmonious, and gently humorous than reality.

A World of Contemporaries

Frederick Stuart Church worked during a vibrant and diverse period in American art history. His career overlapped with artists representing a wide spectrum of styles and movements. Understanding his place requires acknowledging these contemporaries:

Teachers and Mentors: Walter Shirlaw and Lemuel Wilmarth were crucial figures in his education and early career development.

Hudson River School Legacy: While distinct in style, Church worked in the shadow of the preceding generation of landscape painters like Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900) – whose name often caused confusion – Asher B. Durand (1796-1886), and Thomas Cole (1801-1848). Their emphasis on nature provided a backdrop, even as Church took a more imaginative approach.

Fellow Illustrators: He was a leading figure in the Golden Age of Illustration, alongside giants like Howard Pyle (1853-1911), N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), and Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944).

Etching Revival Peers: His work in etching connected him with James McNeill Whistler, Thomas Moran, Mary Nimmo Moran, Robert Swain Gifford, and Stephen Parrish.

Painters of Different Sensibilities: His contemporaries included Tonalists like George Inness (1825-1894), mystics like Albert Pinkham Ryder, and the emerging American Impressionists. Winslow Homer (1836-1910) and Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) represented powerful realist trends.

Animal Painters: William Holbrook Beard offered a more satirical take on anthropomorphism.

Navigating this complex artistic environment, Church maintained his unique vision, borrowing perhaps from the decorative qualities of the Aesthetic Movement but ultimately following his own path focused on whimsical naturalism and illustration.

Later Life and Legacy

Frederick Stuart Church continued to work and exhibit throughout the later decades of the 19th century and into the early 20th century. He maintained his studio in New York City, a familiar and respected figure in the art community. His distinctive style remained popular with a segment of the public and collectors who appreciated his charm, technical skill, and imaginative subjects, even as modernism began to challenge traditional artistic values.

He passed away in New York City in 1924 at the age of 81. His legacy is that of a highly skilled and imaginative artist who successfully bridged the worlds of fine art painting, popular illustration, and printmaking. He holds a special place as one of America's foremost painters of animals, particularly known for his gentle anthropomorphism and romantic sensibility.

Today, his works are held in the collections of major American museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and others. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, Frederick Stuart Church created a body of work that continues to delight viewers with its unique blend of realism, fantasy, and gentle humor, securing his position as an American original.

Conclusion

Frederick Stuart Church navigated the American art world of the late 19th and early 20th centuries with a distinctive and personal vision. From his early detour in business through his formative experiences in the Civil War and his dedicated studies in Chicago and New York, he emerged as a master illustrator, a sensitive painter, and a skilled etcher. His enduring fame rests on his charming and imaginative depictions of animals, often imbued with human-like qualities and placed in idyllic, romantic settings. A member of the New York Etching Club and a frequent contributor to leading magazines, Church brought his unique blend of technical facility and whimsical storytelling to a broad audience. His art offers a gentle, harmonious view of the world, securing his legacy as a beloved and unique figure in American art history.