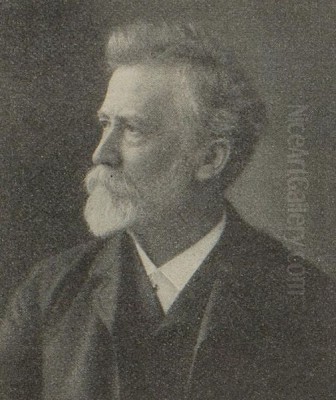

Friedrich von Keller (1840–1914) stands as a significant figure in German art during the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Primarily recognized for his compelling genre scenes and historical paintings, Keller navigated the artistic currents of his time, establishing a distinct voice rooted in realism and narrative depth. His career, largely centered around Stuttgart, saw him rise from a student to an influential professor, leaving a legacy through both his canvases and his teaching. Understanding his work requires placing him within the rich, complex tapestry of German art, a period marked by the dominance of academic traditions, the rise of realism, and the burgeoning influence of impressionism and symbolism.

It is essential, from the outset, to distinguish Friedrich von Keller, the painter, from other notable individuals bearing similar names. He is not Friedrich Ludwig von Keller (1799–1860), the prominent Swiss-German jurist, nor Gottfried Keller (1819–1890), the celebrated Swiss writer. Confusion can also arise with other artists like Ferdinand Keller (1842–1922), a history painter associated with Karlsruhe, or Albert von Keller (1844–1920), a Munich-based painter known for his society portraits and symbolist leanings. This article focuses solely on Friedrich von Keller, the artist born in 1840, whose contributions lie firmly within the realm of painting.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Friedrich Keller was born on October 26, 1840, in Neckarweihingen, a village near Ludwigsburg in the Kingdom of Württemberg. His artistic inclinations led him to pursue formal training at the State Academy of Fine Arts (Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste) in Stuttgart. This institution was a key center for artistic education in southwestern Germany, fostering talent within the region. During his formative years, Keller would have been exposed to the prevailing academic standards, emphasizing draftsmanship, composition, and the study of Old Masters.

The artistic environment in Stuttgart, while perhaps less internationally renowned than Munich or Berlin at the time, provided a solid foundation. Instructors like Bernhard von Neher, known for his historical frescoes, were influential figures at the academy during the mid-19th century. Keller absorbed the principles of careful observation and structured composition, skills that would become hallmarks of his later work. His early development was shaped by the German academic tradition, which valued historical subjects and morally instructive genre scenes.

Development of a Realistic Style

As Keller matured as an artist, his style gravitated towards realism, a movement gaining significant traction across Europe. While perhaps not as radical as the realism championed by Gustave Courbet in France or Wilhelm Leibl in Munich, Keller’s work demonstrated a commitment to depicting scenes with accuracy and a focus on the tangible details of life. He became particularly adept at genre painting, capturing moments from the lives of ordinary people, often peasants or town dwellers from his native Württemberg.

His approach involved meticulous observation of costumes, settings, and human physiognomy. Unlike purely anecdotal genre painters, Keller often imbued his scenes with a sense of narrative weight or psychological insight. His figures are not mere types but individuals engaged in specific activities, conveying emotions ranging from quiet contemplation to strenuous effort. This focus on narrative realism aligned him broadly with trends seen in the Munich School, even though his primary base remained Stuttgart. Artists like Franz von Defregger in Munich explored similar themes of peasant life, though often with a more idealized or romanticized touch compared to Keller's sometimes more sober depictions.

The influence of the Munich School, particularly its emphasis on painterly technique and historical or genre subjects, was pervasive in German art. Keller’s work shows an awareness of these trends, particularly in his handling of light and texture. While maintaining a high degree of finish typical of academic training, his brushwork could, especially in later years, show a slightly looser, more suggestive quality, hinting at an awareness of Impressionistic techniques without fully embracing the style. He remained fundamentally a narrative painter, prioritizing the subject matter and its clear representation.

Professorship and Official Recognition

Keller's growing reputation and skill led to significant professional recognition. In 1877, his contributions to art were acknowledged by King Karl I of Württemberg, who granted him a personal, non-hereditary title of nobility, henceforth allowing him to be known as Friedrich von Keller. This honor underscored his standing within the cultural establishment of Württemberg.

A further testament to his stature came in 1883 when he was appointed Professor at the Stuttgart Art Academy, his alma mater. This position allowed him to shape the next generation of artists in the region. His teaching would likely have emphasized the principles of realism, solid draftsmanship, and narrative composition that defined his own work. Holding this professorship for many years cemented his role as a leading figure in Stuttgart's art scene until his later years. His influence extended through his students, perpetuating a tradition of skilled figurative painting in the region.

Themes and Subject Matter

Friedrich von Keller's oeuvre encompasses a range of subjects, but he is best known for his genre scenes and historical or biblical narratives. His genre paintings often depict rural or small-town life in Württemberg. These are not merely picturesque views but often focus on moments of labor, quiet domesticity, or social interaction. He portrayed farmers, artisans, and families with a degree of empathy and realism that avoids excessive sentimentality. Works like Stonebreakers on a Narrow Bridge exemplify this focus on the dignity and hardship of manual labor, rendered with careful attention to detail and setting.

Historical and biblical subjects also formed a significant part of his output. These paintings allowed Keller to engage with grander themes and more complex compositions. His approach to these subjects was typically grounded in historical research and a desire for accuracy in costumes and settings, characteristic of 19th-century history painting influenced by figures like Karl von Piloty in Munich. However, Keller often focused on the human drama within these historical or religious events, emphasizing emotional interactions and psychological states.

His religious paintings, such as the Foot Washing of Christ by Maria Magdalena (1903), demonstrate his ability to handle traditional themes with sensitivity and technical skill. These later works sometimes show a softer handling of light and form compared to his earlier, more sharply defined style. Keller also undertook portrait commissions, applying his observational skills to capture the likeness and character of his sitters.

Analysis of Major Works

Several key paintings stand out in Friedrich von Keller's body of work, showcasing his stylistic range and thematic concerns.

Daughter of Jairus (Jairi Töchterlein): This painting, depicting the New Testament miracle where Jesus raises a young girl from the dead, became one of Keller's most celebrated works. It demonstrates his skill in composing a multi-figure narrative scene, balancing emotional intensity with a sense of solemnity. The rendering of the figures, the textures of fabrics, and the play of light within the interior setting highlight his technical mastery. The work resonated widely, showcasing his ability to interpret profound religious themes with human sensitivity.

Stonebreakers on a Narrow Bridge (Steinschläger an schmalem Steg): This work is a prime example of Keller's engagement with social realism. It portrays laborers engaged in the physically demanding task of breaking stones, a common theme for realist painters wishing to depict the conditions of the working class. Keller’s composition emphasizes the toil and the rugged environment. The detailed rendering of the figures and their tools, set against a specific landscape, lends the scene authenticity and avoids romanticizing the labor. It stands in dialogue with similar subjects tackled by artists like Courbet, though perhaps with a less overtly political edge.

Minstrel with Wine Glass in a Tavern (Sänger mit Weinglas in einer Schenke, 1880): This painting exemplifies Keller's skill in capturing atmospheric genre scenes. The depiction of a minstrel in an intimate tavern setting allows for exploration of character, mood, and the interplay of light and shadow in an interior space. Such works highlight his interest in everyday social life and his ability to create engaging narrative vignettes. The attention to detail in the setting and the figure's expression invites the viewer to contemplate the story behind the moment.

The Anatomy Lesson (Die Anatomie): Engaging with a theme famously depicted by Rembrandt, Keller’s version likely reflects the 19th-century interest in science and historical accuracy. Such a subject allowed him to demonstrate his skill in portraiture, complex group composition, and the rendering of different textures and surfaces under specific lighting conditions. It places him within a long tradition of artists tackling subjects that bridge art, science, and history.

Foot Washing of Christ by Maria Magdalena (1903): Created later in his career, this painting revisits a poignant biblical episode. It likely reflects the continued demand for religious art and Keller's sustained ability to handle such themes. Stylistically, works from this period might show influences from contemporary trends, perhaps a slightly looser brushwork or a different approach to color, while still retaining the narrative clarity central to his art.

Other works, such as historical scenes like Hexenverfolgung (Witch Hunt) or numerous depictions of peasant gatherings and domestic interiors, further illustrate the breadth of his thematic interests and his consistent focus on human figures within specific, carefully rendered environments.

Keller in the Context of Late 19th-Century German Art

To fully appreciate Friedrich von Keller's contribution, it is helpful to view him alongside his contemporaries and the broader artistic landscape of Germany. The late 19th century was a dynamic period. The academies, particularly in Munich and Berlin, still held considerable sway, promoting history painting (Karl von Piloty, Anton von Werner) and polished genre scenes (Franz von Defregger). Keller’s work aligns with this academic tradition in its emphasis on skill and narrative.

Simultaneously, realism gained ground, most powerfully represented by the circle around Wilhelm Leibl in Munich. Leibl and his associates, like Wilhelm Trübner, advocated for direct observation and often a more painterly technique, focusing on capturing the unvarnished reality of their subjects, frequently rural life. While Keller shared the realists' interest in everyday subjects and accurate depiction, his style generally retained a more detailed finish and narrative structure compared to the often more purely formal concerns of the Leibl circle.

The period also saw the rise of German Impressionism, spearheaded by artists like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. These artists embraced lighter palettes, looser brushwork, and a focus on capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere. Fritz von Uhde uniquely blended impressionistic techniques with religious and social realist themes. While Keller’s later work might show a subtle softening or brightening, he never fully adopted an impressionistic style, remaining closer to the realist-academic tradition. His contemporary in Stuttgart, Christian Landenberger (though younger), moved more decisively towards Impressionism.

Furthermore, Symbolism offered another artistic direction, explored by figures like Arnold Böcklin and Franz von Stuck, who delved into mythology, allegory, and dreamlike states. Keller’s art, with its focus on tangible reality and clear narratives, stands apart from the evocative ambiguities of Symbolism. Similarly, the expressive intensity beginning to emerge in the work of artists like Lovis Corinth or the early Expressionists was distinct from Keller's more measured approach.

Keller can thus be positioned as a master within the established traditions of genre and history painting, adapting realist principles to his narrative aims. He represented a significant regional force in Stuttgart, maintaining high standards of craftsmanship while navigating the diverse artistic currents of his time. He worked alongside contemporaries like Hans Thoma, who developed a unique style blending realism and idealism, and Gotthardt Kuehl, known for his impressionistic cityscapes and interiors.

Legacy and Conclusion

Friedrich von Keller passed away on September 8, 1914, in Munich, although his artistic life and influence were predominantly linked to Stuttgart. His legacy rests on his substantial body of work, characterized by technical proficiency, narrative clarity, and a sensitive depiction of human life, whether in everyday settings or historical contexts. As a long-serving professor at the Stuttgart Art Academy, he played a crucial role in educating artists and upholding standards of figurative painting in Württemberg.

His paintings offer valuable insights into the social and cultural life of his time, particularly in southwestern Germany. While perhaps not an avant-garde innovator who radically broke with tradition, Keller was a highly respected artist who skillfully synthesized academic training with realist observation. His work found appreciation among the public and official circles, evidenced by his ennoblement and professorship.

Today, his paintings are held in various German museums, particularly in Stuttgart, and occasionally appear at auction. They serve as important examples of German realism and narrative painting from a period of significant artistic transition. Friedrich von Keller remains a testament to the enduring power of skilled representation and storytelling in art.

Clarifying the Name

It bears repeating that Friedrich von Keller (1840–1914), the painter discussed here, should not be confused with his namesakes. The jurist Friedrich Ludwig von Keller (1799–1860) was a legal scholar and politician. The writer Gottfried Keller (1819–1890) was a major figure in Swiss literature. The inventor Friedrich Gottlieb Keller (1816–1895) pioneered wood pulp paper production. Within the art world itself, Ferdinand Keller (1842–1922) was a history painter known for works like the Apotheosis of Emperor Wilhelm I, associated with the Karlsruhe school, while Albert von Keller (1844–1920) was a Munich Secession member noted for his elegant portraits and mystical scenes. Recognizing these distinctions is crucial for accurately assessing the life and work of Friedrich von Keller, the Stuttgart-based master of genre and history painting.