Georges Antoine Rochegrosse stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in French art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Versailles in 1859 and passing away in El Biar, near Algiers, in 1938, his life spanned a period of dramatic artistic change. Rochegrosse carved a distinct niche for himself primarily as a history painter, but his work also embraced the currents of Symbolism and Orientalism, resulting in a rich and complex oeuvre characterized by dramatic intensity, meticulous detail, and a powerful, often sensual, naturalism.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Rochegrosse's upbringing provided a fertile ground for his future artistic inclinations. He grew up in a household steeped in literature and culture. His stepfather was the renowned Parnassian poet Théodore de Banville, a connection that brought the young Rochegrosse into contact with towering figures of the French literary world, including Victor Hugo and the Goncourt brothers. This early immersion in narrative, history, and poetic expression undoubtedly shaped his artistic vision, predisposing him towards grand themes and evocative storytelling.

His formal artistic training took place in the heart of the Parisian art establishment. Rochegrosse studied at the prestigious Académie Julian, a popular alternative to the official École des Beaux-Arts, though he also attended the latter. At these institutions, he honed his skills under the tutelage of respected academic painters. His teachers included Alfred Dehodencq, known for his Orientalist scenes and genre paintings, as well as Jules Joseph Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger, both prominent figures in the academic tradition, known for their polished technique and historical or mythological subjects. This training provided him with a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the academic methods valued at the time.

Despite his evident talent and rigorous training, Rochegrosse faced early setbacks in the traditional path to artistic success. He attempted the highly coveted Prix de Rome competition on two occasions but failed to secure the grand prize, which offered a funded period of study in Rome. This prize was a significant marker of success for aspiring history painters, and missing out might have spurred him to find recognition through other avenues, primarily the annual Paris Salon.

Salon Debut and Early Recognition

Rochegrosse made his impactful debut at the Paris Salon in 1882 with the painting Vitellius Dragged Through the Streets of Rome by the People. This work immediately garnered attention. Its subject matter – a brutal episode from Roman history depicting the ignominious end of the Roman Emperor Vitellius – was characteristic of the historical genre popular at the Salon. The painting was noted for its dramatic composition, its unflinching depiction of mob violence, and its naturalistic rendering of figures and emotions. It signaled Rochegrosse's arrival as a painter capable of tackling large-scale historical narratives with technical skill and emotional force.

This debut marked the beginning of a successful period for Rochegrosse at the Salon. The following year, in 1883, he exhibited Andromaque (Andromache). This monumental canvas, depicting a harrowing scene from the aftermath of the Trojan War based on Racine's tragedy, further solidified his reputation. The work shows the captive Trojan queen Andromache fainting as her son Astyanax is about to be thrown from the city walls, surrounded by the brutal realities of war – violence, death, and despair.

Andromaque was both praised and controversial. Its scale, dramatic intensity, and meticulous attention to historical (or perceived historical) detail were admired. Rochegrosse demonstrated a keen interest in archaeological accuracy, attempting to reconstruct the setting and costumes with care. However, the painting's graphic depiction of violence, including severed heads and bloodied bodies, alongside the prominent nudity of some figures, shocked some contemporary viewers and critics, who found it overly gruesome or sensational. Despite, or perhaps because of, the controversy, the work was a major success, earning Rochegrosse a medal at the Salon and confirming his status as a leading history painter of his generation.

Masterworks of History and Myth

Following his early successes, Rochegrosse continued to produce large, ambitious paintings drawing on historical, mythological, and literary sources. His works often focused on moments of intense drama, violence, or decadence, rendered with a characteristic blend of academic precision and heightened emotionalism. He possessed a talent for orchestrating complex multi-figure compositions and conveying powerful narratives through gesture, expression, and dynamic arrangement.

One of his most famous works from this period is The Fall of Babylon (La chute de Babylone), exhibited at the Salon of 1891. This vast, sprawling canvas depicts the legendary sack of the ancient city, reveling in the chaos, destruction, and debauchery associated with the event. Inspired by historical accounts and perhaps Flaubert's Salammbô, the painting is a tour-de-force of dramatic staging, filled with writhing figures, exotic details, and a sense of overwhelming catastrophe. It exemplifies Rochegrosse's fascination with the perceived brutality and sensuality of the ancient world.

Another significant historical work is The Death of Caesar (La Mort de César), painted later in his career. Revisiting a pivotal moment in Roman history, Rochegrosse depicted the assassination of Julius Caesar within the Roman Senate. True to his style, the painting focuses on the dramatic climax, capturing the chaos, betrayal, and violence of the event with vivid detail and emotional intensity. Such works cemented his reputation as a painter who could bring the past to life, albeit often focusing on its most tumultuous and violent aspects.

These historical paintings showcase Rochegrosse's strengths: his ability to manage complex compositions, his detailed rendering of textures and surfaces, his interest in historical reconstruction, and his flair for the dramatic. While rooted in the academic tradition taught by masters like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Lawrence Alma-Tadema in terms of finish and historical setting, Rochegrosse infused his scenes with a raw energy and emotionalism that bordered on the Romantic, distinguishing his work from more staid academic productions.

Symbolism and The Knight of the Flowers

While best known for his historical epics, Rochegrosse's artistic interests were not confined to that genre. He was also receptive to the Symbolist movement, which gained prominence in the late nineteenth century, emphasizing subjectivity, spirituality, and the evocative power of suggestion over direct representation. This influence is most famously seen in his 1894 painting, Le Chevalier aux Fleurs (The Knight of the Flowers), now housed in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

This painting departs significantly from the historical violence of works like Andromaque or The Fall of Babylon. It depicts a scene inspired by Richard Wagner's opera Parsifal. The knight Parsifal, clad in armour, walks resolutely through a magical garden filled with seductive flower maidens (the Blumenmädchen) who attempt to lure him from his sacred quest. The atmosphere is one of enchantment and temptation, contrasting the knight's purity and determination with the sensual allure of the surrounding figures.

Le Chevalier aux Fleurs is a key work of French Symbolism. Its themes of spiritual struggle, temptation versus purity, and the mystical quest align perfectly with Symbolist preoccupations. Stylistically, while retaining Rochegrosse's characteristic detail, the painting employs a brighter palette and a more decorative quality, particularly in the rendering of the flowers and the ethereal female figures. It demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with the leading artistic currents of his time, moving beyond pure historical narrative towards allegory and mood. Other artists exploring similar Symbolist themes included Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, though Rochegrosse's approach remained grounded in a more solid, naturalistic rendering of form.

Orientalism and the Algerian Influence

Like many European artists of the nineteenth century, Rochegrosse was drawn to the perceived exoticism and sensuality of the "Orient," a term broadly encompassing North Africa and the Middle East. This fascination, known as Orientalism, manifested in his work through choices of subject matter, setting, and a vibrant colour palette. His interest was likely encouraged by teachers like Dehodencq and contemporaries such as Benjamin-Constant or Jean-Léon Gérôme, who were renowned Orientalist painters.

Rochegrosse's connection to the Orient became deeply personal later in his life. He eventually moved to El Biar, a suburb of Algiers in French Algeria, where he spent his final years and ultimately died in 1938. This direct experience of North African life and landscape profoundly influenced his later work. He became an active member of the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français (Society of French Orientalist Painters) and even served as a juror for the Salon des Artistes Algériens in Algiers.

His Orientalist works often blend biblical or mythological themes with North African settings and details, creating a unique fusion. He painted scenes inspired by Flaubert's Salammbô, set in ancient Carthage, and explored themes from the Bible and mythology, often imbuing them with a distinctly North African atmosphere. These works are characterized by rich colours, attention to decorative detail in costumes and architecture, and a continued interest in dramatic and sensual themes. Artists like Étienne Dinet, who also lived and worked in Algeria, shared this deep engagement with the local culture, though Rochegrosse often maintained a more fantastical or historical lens.

Rochegrosse as Illustrator

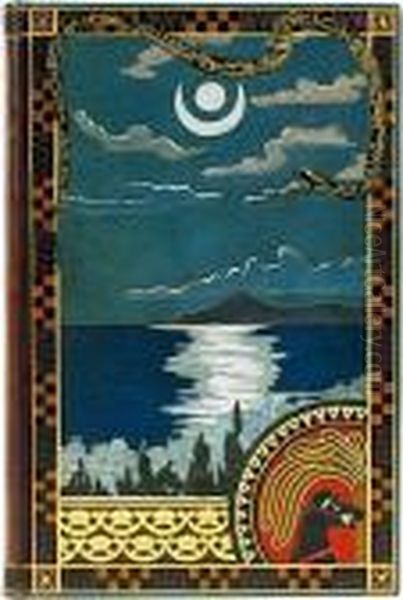

Beyond his large-scale paintings, Rochegrosse was also a prolific and accomplished illustrator. He created illustrations for numerous books, bringing his dramatic style and meticulous detail to the printed page. This aspect of his career allowed his work to reach a wider audience and demonstrated his versatility across different mediums.

His illustrative work often mirrored the themes found in his paintings. He produced illustrations for editions of classical texts like Petronius's Satyricon and Homer's Odyssey, tackling ancient narratives with his characteristic flair. He was particularly drawn to themes involving powerful or dangerous women, creating notable illustrations for works centered around the figure of Salome, such as Gustave Flaubert's Hérodias or Oscar Wilde's Salome. These illustrations often emphasized the sensuality, decadence, and dramatic tension inherent in the stories. His skill in composition and detailed rendering translated effectively to the smaller scale of book illustration.

Style and Technique Summarized

Georges Antoine Rochegrosse's artistic style is multifaceted, reflecting the diverse influences and movements of his time, yet unified by certain core characteristics. His foundation was firmly rooted in the French Academic tradition, evident in his skilled draughtsmanship, polished finish, and preference for historical and mythological subjects. However, he infused this academic base with a potent dose of Romantic drama and emotional intensity.

Naturalism, particularly a form described as "sensual" or "emotional naturalism," is central to his work. He aimed for a high degree of realism in depicting figures, textures, and settings, often based on careful research (including archaeological details). Yet, this naturalism was employed in the service of heightened emotion and dramatic effect, sometimes pushing towards the theatrical or even sensational.

Symbolist elements appear notably in works like Le Chevalier aux Fleurs, where mood, allegory, and suggestion take precedence over literal narrative. His engagement with Orientalism brought vibrant colour, exotic settings, and a focus on sensuality to many of his paintings and illustrations. Throughout his career, Rochegrosse demonstrated a mastery of large, complex compositions, a fascination with historical and exotic detail, and a consistent ability to convey powerful, often visceral, emotions. He was a painter of grand narratives, dramatic moments, and intense feelings.

Contemporaries and Connections

Rochegrosse operated within a vibrant and evolving Parisian art world. His teachers, Jules Joseph Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger, connected him directly to the heart of the Academic establishment. He exhibited alongside countless artists at the annual Salons, competing for attention and honours. His historical and Orientalist works place him in dialogue with prominent figures like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, and Benjamin-Constant, who explored similar themes, albeit often with different stylistic emphases.

His Symbolist leanings connect him to artists such as Gustave Moreau, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Odilon Redon, and even Belgian Symbolists like Fernand Khnopff, although Rochegrosse generally maintained a more concrete and less ethereal style than many of them. His membership in the Société des Peintres Orientalistes Français placed him alongside specialists in that field, including Nasreddine Dinet (Étienne Dinet). Furthermore, his family connections through Théodore de Banville linked him to the literary elite, including Victor Hugo and the Goncourt brothers, highlighting the cross-pollination between literature and the visual arts during this period.

Controversies and Reception

Despite achieving considerable success at the Salon and receiving official recognition, Rochegrosse's work was not without controversy, and his critical reception fluctuated. The explicit violence and nudity in early works like Andromaque provoked debate, with some critics finding them overly graphic or pandering to sensationalism. Similarly, the dramatic intensity of paintings like Vitellius was sometimes criticized as being exaggerated or melodramatic.

While his technical skill was generally acknowledged, the perceived excesses in his subject matter and emotional pitch sometimes drew censure. Furthermore, as artistic tastes evolved towards the end of the nineteenth century with the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, Rochegrosse's adherence to a more academic, narrative style meant his work fell out of favour with the avant-garde, though he continued to exhibit and receive commissions.

His later Symbolist and religious works also met with mixed reactions, sometimes seen as lacking the immediate impact or relevance of his earlier historical dramas. There's also the suggestion that while artistically significant, he perhaps lacked broader social recognition or fame compared to some contemporaries. His personal life also intertwined with his art; his wife, Marie Leblanc, whom he was married to for nearly three decades, frequently served as his model, appearing in works like The Masked Woman (Femme au masque), potentially influencing the emotional depth of his portrayal of female figures.

Later Life, Legacy, and Contemporary Evaluation

Rochegrosse spent his later years primarily in Algeria, continuing to paint and remaining active in the local art scene. His dedication to his art was recognized with official honours; he was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1892 and later received the prestigious Medal of Honour at the Salon of 1906 for his painting La Joie Rouge (The Red Joy). His works were exhibited not only in France but also internationally, including in Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, indicating a degree of renown beyond French borders.

Today, Georges Antoine Rochegrosse is recognized as an important figure within the context of late 19th and early 20th-century French painting. While perhaps overshadowed during the modernist era, his work has been re-evaluated and appreciated for its technical mastery, its dramatic power, and its unique synthesis of Academicism, Romanticism, Symbolism, and Orientalism. He is considered a significant exponent of the historical genre painting that flourished at the Salons, known for bringing ancient and historical worlds to life with visceral intensity.

His legacy lies in his powerful, often unsettling, depictions of historical drama, his contribution to Symbolist imagery with works like Le Chevalier aux Fleurs, and his engagement with Orientalist themes, enriched by his personal experience in North Africa. His paintings offer a fascinating window into the artistic tastes and cultural preoccupations of his time, particularly the fascination with history, myth, exoticism, and intense emotion. While sometimes criticized for sensationalism, his ability to create visually stunning and emotionally charged narratives remains undeniable. His works continue to captivate viewers with their blend of meticulous detail and dramatic force, securing his place as a distinctive voice in the rich tapestry of French art.

Conclusion

Georges Antoine Rochegrosse navigated the complex artistic landscape of fin-de-siècle France with a distinctive vision. From the brutal realism of his early historical paintings to the mystical allure of his Symbolist works and the vibrant exoticism of his Orientalist scenes, he consistently demonstrated technical brilliance and a flair for the dramatic. His immersion in literature, history, and myth, combined with his academic training and personal experiences, resulted in an oeuvre that is both spectacular and deeply felt. Though subject to the shifting tides of critical favour, Rochegrosse's powerful compositions, meticulous detail, and exploration of intense human emotion ensure his enduring significance as a master of historical and imaginative painting. His art remains a compelling testament to the enduring power of narrative and the dramatic possibilities of the canvas.