Rudolph Friedrich Wasmann (1805–1886) stands as a notable, if sometimes overlooked, figure in 19th-century German art. His career spanned a period of significant artistic transition, from the waning embers of Neoclassicism through the height of Romanticism and into the burgeoning era of Realism and the intimate sensibilities of the Biedermeier period. Born in Hamburg and dying in Meran (Merano), then part of Austria-Hungary, Wasmann's artistic journey took him through key artistic centers like Dresden, Munich, and Rome, exposing him to diverse influences and shaping his unique, often introspective, style. He is particularly recognized for his sensitive portraits, meticulously observed landscapes, and a distinctive use of the "window view" motif, which imbued his scenes with a quiet, contemplative atmosphere.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Friedrich Wasmann was born on August 8, 1805, in Hamburg, a bustling Hanseatic port city that fostered a pragmatic and observant worldview. His artistic inclinations were likely nurtured early on, as his father, Johann Christian Friedrich Wasmann, was also an artist. This familial connection undoubtedly provided initial exposure to the tools and techniques of painting and drawing, laying a foundation for his future career. Hamburg, at the time, was developing its own artistic identity, distinct from the more established academies in southern Germany.

To further his artistic education, Wasmann sought training in more prominent artistic hubs. He studied at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, a venerable institution that had been a crucible for German Romanticism, famously associated with figures like Caspar David Friedrich. While Friedrich's more overtly symbolic and spiritual landscapes differed from Wasmann's later, more naturalistic approach, the Romantic emphasis on individual feeling and the sublime beauty of nature would have been part of the artistic air he breathed in Dresden.

Following his time in Dresden, Wasmann continued his studies in Munich, another major center for the arts in the German Confederation. The Munich Academy was also a vibrant place, attracting artists from across Europe. Here, he would have encountered different artistic currents, including the historical painting tradition and emerging realist tendencies. This period of academic training in both Dresden and Munich equipped him with a solid technical grounding and exposed him to the prevailing artistic debates and styles of the era.

The Pivotal Italian Sojourn

Like many Northern European artists of his generation, Wasmann felt the irresistible pull of Italy, the classical cradle of art and a landscape steeped in history and radiant light. From 1832 to 1835, he resided in Rome, a period that proved immensely formative for his artistic development. Rome was not just a place of ancient ruins and Renaissance masterpieces; it was a vibrant international artists' colony.

During his time in the Eternal City, Wasmann came into contact with several influential figures. He met members of the Nazarene movement, a group of German-speaking Romantic painters who aimed to revive honesty and spirituality in Christian art, drawing inspiration from early Renaissance masters like Raphael and Albrecht Dürer. Key among these was Friedrich Overbeck, a leading figure of the Nazarenes. While Wasmann did not fully adopt the often overtly religious or medievalizing themes of the Nazarenes, their emphasis on clear drawing, heartfelt expression, and a certain purity of form likely resonated with him.

He also encountered the venerable Austrian landscape painter Joseph Anton Koch, whose heroic and idealized Italian landscapes had a profound impact on a generation of artists. Koch's deep understanding of classical composition and his ability to convey the grandeur of the Italian countryside offered a powerful model. Another significant acquaintance was the celebrated Danish Neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, whose studio was a major attraction in Rome. While Thorvaldsen's cool classicism might seem at odds with Romantic sensibilities, his international fame and the intellectual ferment around him contributed to the rich artistic environment Wasmann experienced. It is also noted that he was influenced by the work of the German history painter Carl von Piloty during this period, who himself would later become an influential teacher in Munich.

Wasmann's Roman period was productive. He created numerous landscape studies and paintings, capturing the distinctive light and atmosphere of the Italian Campagna. Works from this era often show a heightened sensitivity to color and a desire to record direct observations of nature, a practice that aligned with the growing interest in plein-air sketching. His famous painting, Die Tarantellen (The Tarantella), depicting a lively dance scene, likely dates from or was inspired by his Italian experiences, showcasing his ability to capture genre scenes with vivacity. Another work, Tanz nach der Weinlese (Dance after the Grape Harvest), similarly reflects his engagement with Italian folk life.

Return to Germany and Later Years in Meran

After his transformative years in Italy, Wasmann returned to Germany. He spent time in his native Hamburg, where he continued to paint, focusing on portraits and landscapes. Hamburg's artistic scene, while perhaps not as grand as Munich or Berlin, had its own distinct character, with artists like Christian Morgenstern and Adolph Friedrich Vollmer contributing to a local tradition of realistic landscape painting. Wasmann's work found a place within this context, though his more introspective and sometimes experimental approach might not have always aligned with mainstream tastes.

Later in his life, in 1868, Wasmann moved to Meran in South Tyrol (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now Merano, Italy). This picturesque spa town, nestled in the Alps, offered a new range of landscapes and a different cultural environment. He continued to be active as a painter in Meran, producing landscapes and portraits until his death on May 10, 1886. His time in Meran represents the final phase of his artistic journey, likely characterized by a mature synthesis of his earlier experiences and influences.

The Hamburger Kunsthalle today holds a significant collection of Wasmann's works, including many drawings and oil sketches, testament to his connection with his birth city and his enduring, if quiet, contribution to German art. His autobiography, Ein deutsches Künstlerleben, von ihm selbst geschildert (A German Artist's Life, Described by Himself), provides invaluable insights into his life, his artistic thoughts, and the circles in which he moved.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Friedrich Wasmann's art is characterized by a blend of Romantic sensibility, Biedermeier intimacy, and an early form of Realism. He was not a painter of grand historical narratives or dramatic mythological scenes, but rather an artist who found significance in the everyday, the personal, and the closely observed natural world.

Landscape Painting and the Window Motif:

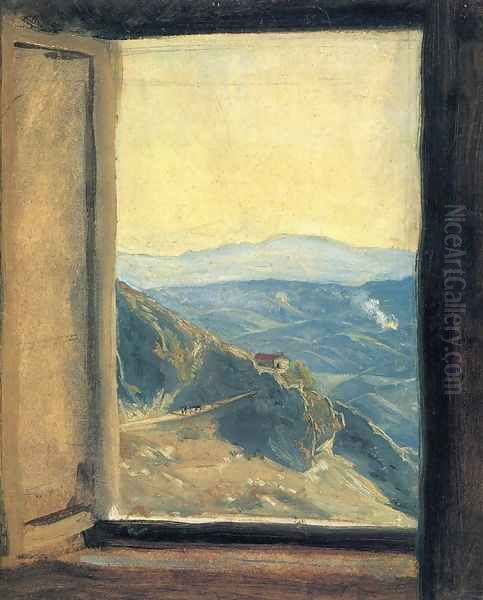

Wasmann's landscapes are notable for their careful observation and subtle rendering of light and atmosphere. He was particularly adept at capturing the specific character of a place, whether it was the sun-drenched plains of the Italian Campagna or the more muted tones of Northern Germany. A distinctive feature in his oeuvre is the "window view" or Fensterblick. Works like View from a Window (1832) or Open Window (1830-35) use the architectural frame of a window to mediate the viewer's gaze onto the landscape beyond. This device creates a sense of interiority and contemplation, a common theme in Romantic and Biedermeier art, suggesting a longing for the outside world from a secure, domestic space. The window acts as both a connection and a separation, enhancing the feeling of depth and inviting the viewer into a quiet, personal moment. This motif was also explored by contemporaries like Caspar David Friedrich and later by artists such as Adolph Menzel, though each invested it with their own particular meaning.

Portraiture:

Wasmann was a skilled portraitist, known for his sensitive and unpretentious depictions of individuals. His portraits often focus on capturing the sitter's personality and inner life rather than on ostentatious display. He painted numerous portraits of women and children, such as Mädchen mit Zopfrisur (Portrait of a Girl with Braids), where the innocence and directness of the subject are conveyed with gentle empathy. These works align closely with the Biedermeier ethos, which valued domesticity, family, and the portrayal of individual character. His approach was often direct, with a focus on clear delineation of features and a subtle use of color to model form. He reportedly received numerous portrait commissions in Rome through his connections with fellow artists like Nolken and Bockelmann.

Naturalism and Detail:

A strong current of naturalism runs through Wasmann's work. He possessed a keen eye for detail, evident in his studies of plants, such as Study of a Grapevine, where the textures and forms of nature are rendered with precision. This commitment to accurate observation links him to the burgeoning realist tendencies of the 19th century. However, his naturalism is rarely cold or purely objective; it is usually infused with a lyrical quality and a sense of personal engagement with the subject.

Use of Color and Light:

Wasmann's palette could vary depending on the subject and location. His Italian scenes often feature brighter, warmer colors, reflecting the Mediterranean light. In some works, he experimented with quite vivid pigments, including turquoise and amethyst, to enhance the expressive power of his color. He was particularly interested in the effects of light, whether it was the diffuse light of an interior, the clear light of an open landscape, or the subtle atmospheric changes of different times of day. His smaller, experimental oil sketches were often explorations of these fleeting effects.

Romantic and Biedermeier Sensibilities:

While trained in academic traditions, Wasmann's art is deeply imbued with the spirit of Romanticism, particularly in its emphasis on individual feeling, the beauty of nature, and a certain introspective mood. His connection with the Nazarenes in Rome further exposed him to Romantic ideals. Simultaneously, much of his work, especially his portraits and intimate landscapes, resonates strongly with the Biedermeier style. This Central European artistic and cultural period (roughly 1815-1848) emphasized domesticity, simplicity, piety, and a focus on the private sphere. Wasmann's quiet, unassuming art, with its appreciation for the small beauties of life and nature, fits well within this framework. Artists like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller in Austria or Ludwig Richter in Germany are other exemplars of Biedermeier painting.

Analysis of Key Works

Several works stand out in Friedrich Wasmann's oeuvre, illustrating his characteristic themes and stylistic approaches.

View from a Window (Blick aus dem Fenster), 1832:

This painting, created during his time in Italy, is perhaps one of his most iconic. It exemplifies his use of the window motif. The viewer looks out from a shadowed interior, through an open window with simple wooden shutters, onto a sunlit Italian landscape, likely the Campagna. The window frame neatly divides the composition, creating a strong sense of depth and perspective. The contrast between the dim interior and the bright exterior is palpable. The scene outside is serene – rolling hills, scattered trees, and a distant building under a clear sky. The painting evokes a sense of quiet contemplation, a peaceful observation of the world from a sheltered vantage point. It captures a moment of stillness and introspection, characteristic of both Romantic and Biedermeier sensibilities. The careful rendering of light and the subtle gradations of color in the landscape demonstrate Wasmann's observational skills.

Mädchen mit Zopfrisur (Portrait of a Girl with Braids):

This portrait showcases Wasmann's talent for capturing the unadorned charm and innocence of youth. The young girl is presented directly, her gaze meeting the viewer's with a quiet confidence. Her hair, neatly braided and coiled, frames a face rendered with sensitivity and attention to individual features. The lighting is soft, and the background is typically understated, ensuring that the focus remains entirely on the sitter. There is no attempt at idealization or flattery; instead, Wasmann seeks an honest and empathetic portrayal. This work is a fine example of Biedermeier portraiture, valuing sincerity and individual character over grandeur.

Die Tarantellen (The Tarantella):

This painting, likely inspired by his Italian sojourn, depicts a lively folk dance, the tarantella, traditionally performed in Southern Italy. It shows Wasmann's ability to handle more complex figural compositions and to convey a sense of movement and energy. The scene is filled with dancers in traditional costume, caught in the midst of their exuberant performance. The colors are vibrant, and the composition is dynamic, capturing the spirit of the communal celebration. While different in mood from his quieter landscapes and portraits, Die Tarantellen demonstrates his versatility and his engagement with the local culture he encountered in Italy. It shares a thematic interest in folk life with other contemporary artists who traveled to Italy, such as Louis Léopold Robert.

Study of a Grapevine (Studie einer Weinrebe):

This detailed study highlights Wasmann's commitment to the close observation of nature. The intricate structure of the grapevine, its leaves, tendrils, and fruit, are rendered with botanical accuracy yet also with an artist's eye for form and texture. Such studies were crucial for 19th-century artists, serving as preparatory work for larger compositions or as exercises in understanding the natural world. This piece underscores the empirical, almost scientific, aspect of his artistic practice, which coexisted with his more Romantic inclinations. It shows an appreciation for the inherent beauty of natural forms, a theme also explored by artists like Philipp Otto Runge, albeit with more symbolic intent.

Blick ins Etschthal mit Kindern auf einem Hügel (View into the Adige Valley with Children on a Hill), 1830:

Created before his main Italian period, this work already shows his interest in landscape and the inclusion of figures that animate the scene without dominating it. The view into the Adige Valley (Etschtal) suggests an early appreciation for alpine scenery. The children on the hill add a touch of genre and human interest, a common feature in Biedermeier landscapes where nature is often depicted as a harmonious setting for human life. The composition likely balances a broad vista with carefully observed details in the foreground.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Artistic Circles

Friedrich Wasmann's artistic journey was shaped by his interactions with a diverse array of contemporary artists and his immersion in various artistic circles.

In Hamburg, he was part of a local art scene that included figures like Christian Morgenstern (1803-1867) and Adolph Friedrich Vollmer (1806-1875). Morgenstern, in particular, was a significant landscape painter who, like Wasmann, spent time in Munich and was known for his realistic depictions of nature. They were contemporaries who both contributed to the development of realism in Northern Germany. The great Norwegian Romantic painter Johan Christian Dahl (1788-1857), who spent much of his career in Dresden but also had connections to Hamburg, was another influential figure in German and Scandinavian landscape painting whose work emphasized direct observation of nature.

His time in Dresden would have brought him into the orbit of the legacy of Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), the preeminent German Romantic landscape painter. While their styles differed, Friedrich's profound impact on the perception and depiction of nature in German art was undeniable. Other Dresden artists like Ludwig Richter (1803-1884), known for his idyllic landscapes and illustrations, represented the Biedermeier aspect of German Romanticism.

In Rome, his encounters were particularly significant. His association with Friedrich Overbeck (1789-1869) and other Nazarenes like Peter von Cornelius (1783-1867, though more active in Munich later) exposed him to their ideals of artistic renewal through religious piety and the study of early Renaissance masters. The Austrian landscapist Joseph Anton Koch (1768-1839) was a towering figure whose heroic Italian landscapes influenced many. The Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844) was an international celebrity in Rome, representing the Neoclassical tradition. Wasmann also knew the German painter Carl Wagner (1796-1867) in Rome. These interactions provided a rich tapestry of artistic ideas, from Romantic spiritualism to Neoclassical form and detailed naturalism.

The influence of Carl von Piloty (1826-1886), though younger, is mentioned in relation to Wasmann's Roman period. Piloty later became a leading history painter and influential professor at the Munich Academy, championing a form of realism in historical subjects. Other Munich artists of the broader era included figures like Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871), known for his late Romantic, fairy-tale subjects, and Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885), the quintessential Biedermeier genre painter. While direct connections to all these Munich figures are not always clear for Wasmann, they formed part of the artistic milieu of one of his study locations.

Wasmann's art, with its blend of intimacy and observation, also shares affinities with the Danish Golden Age painters like Wilhelm Bendz (1804-1832) and Christen Købke (1810-1848), who similarly excelled in sensitive portraiture and luminous, carefully constructed depictions of their everyday surroundings.

Connection to Art Movements

Friedrich Wasmann's work is best understood at the intersection of several key 19th-century art movements:

Romanticism: This was the dominant artistic and intellectual movement of the early 19th century. Wasmann's emphasis on individual feeling, his contemplative landscapes, the evocative use of the window motif, and his connection with the Nazarenes all place him firmly within the broader Romantic tradition. Unlike the more dramatic or sublime aspects of Romanticism found in, for example, Caspar David Friedrich or Carl Blechen, Wasmann's Romanticism was often quieter and more personal.

Nazarenes: His direct contact with Friedrich Overbeck and other Nazarenes in Rome was significant. While he didn't become a Nazarene in the strict sense of adopting their predominantly religious subject matter or their communal workshop practices, their emphasis on clear drawing, sincerity of expression, and inspiration from early Italian and German masters likely reinforced his own tendencies towards careful craftsmanship and heartfelt depiction.

Biedermeier: This cultural and artistic period, flourishing in German-speaking lands and Scandinavia between roughly 1815 and 1848, is perhaps the most fitting context for much of Wasmann's art. Biedermeier art valued domesticity, simplicity, piety, and the depiction of everyday life and modest pleasures. Wasmann's intimate portraits, his quiet window views, and his unpretentious landscapes resonate strongly with Biedermeier ideals. His focus on the personal and the closely observed, rather than the heroic or monumental, aligns perfectly with this sensibility.

Early Realism: Wasmann's commitment to direct observation of nature, his detailed studies like Study of a Grapevine, and the naturalistic rendering in his portraits also connect him to the emerging currents of Realism. This was not the politically charged Realism of Gustave Courbet in France, but rather a more general 19th-century trend towards depicting the world with greater fidelity and less idealization. His outdoor studies and his precise rendering of details show an empirical approach that was a hallmark of early realist tendencies.

Wasmann did not rigidly adhere to any single movement but rather synthesized elements from each, creating a personal style that was both of its time and uniquely his own.

Legacy and Art Historical Standing

Friedrich Wasmann's position in art history is somewhat nuanced. He was not one of the towering, revolutionary figures who dramatically altered the course of art, nor did he achieve the widespread international fame of some of his contemporaries. However, his work holds a distinct and valuable place, particularly within the context of German Romanticism and Biedermeier art.

His contributions are most evident in his sensitive and introspective approach. His window views are considered significant examples of this motif, capturing a particular mood of quiet contemplation and connection with the outside world. His portraits are valued for their psychological insight and their unpretentious honesty, offering a glimpse into the lives of ordinary individuals of his time. His landscape sketches and studies demonstrate a keen observational skill and an early engagement with plein-air practice.

There has been some discussion or "controversy" regarding his art historical standing, primarily in the sense that his achievements may have been historically undervalued or overshadowed by more prominent names. Some critics and art historians argue that the experimental nature of his smaller oil sketches and his nuanced explorations of light and atmosphere were not fully appreciated during his lifetime or in subsequent art historical narratives. He was, perhaps, too quiet, too introspective for an era that also celebrated grander gestures. In Hamburg, for instance, he might not have achieved the same level of recognition as a figure like Christian Morgenstern.

However, institutions like the Hamburger Kunsthalle, which holds a substantial collection of his works, have played a crucial role in preserving his legacy and enabling a reassessment of his contributions. Modern scholarship tends to view him as an important representative of the Biedermeier sensibility in Northern Germany, an artist who skillfully blended Romantic feeling with careful observation. His autobiography also provides a valuable contemporary account of an artist's life in the 19th century.

While he may remain a more specialized interest compared to giants like Caspar David Friedrich, Wasmann's art offers a rewarding exploration for those interested in the quieter, more personal currents of 19th-century European painting. His work reveals an artist of considerable skill, sensitivity, and a unique vision that captured the subtle beauties of his world.

Conclusion

Friedrich Wasmann was an artist whose career navigated the rich and complex artistic landscape of 19th-century Germany and Italy. From his early training in Hamburg, Dresden, and Munich to his formative years in Rome and his later life in Meran, he absorbed diverse influences while cultivating a distinctive artistic voice. His paintings, characterized by a blend of Romantic introspection, Biedermeier intimacy, and an emerging realist observation, offer a unique window into his era.

His sensitive portraits, meticulously observed landscapes, and particularly his evocative "window views" reveal an artist attuned to the subtle nuances of light, atmosphere, and human emotion. While perhaps not always in the brightest spotlight of art history, Friedrich Wasmann's legacy endures through his thoughtful and beautifully crafted works, which continue to resonate with viewers for their quiet honesty and gentle poetry. He remains a significant figure for understanding the more personal and introspective dimensions of German art in a century of profound change.