The mid-nineteenth century in American art was a period of burgeoning national identity, with landscape painting, particularly the Hudson River School, often taking center stage. Yet, within this vibrant artistic milieu, other genres flourished, contributing significantly to the richness and diversity of American visual culture. Among these, still life painting held a distinct and cherished place, offering intimate glimpses into the era's appreciation for nature's bounty and the quiet beauty of everyday objects. Paul Lacroix (1827-1869), a painter of French or Swiss origin who made America his home, emerged as a notable figure in this tradition, leaving behind a legacy of meticulously rendered and evocative still lifes that continue to captivate audiences.

Early Life and Emigration to America

Born in 1827, Paul Lacroix's early life was rooted in Europe, though specifics regarding his birthplace—whether France or Switzerland—remain somewhat elusive in detailed records. What is clear is that, like many Europeans of his time seeking new opportunities or a different cultural environment, Lacroix made the transformative journey across the Atlantic, immigrating to the United States. He settled in New York City, a rapidly growing metropolis that was fast becoming a significant cultural and artistic hub in the young nation.

His presence in New York City is first formally documented in the city's commercial directories in 1857. This suggests that by this time, he was establishing himself, likely already pursuing his artistic endeavors. New York in the 1850s and 1860s provided a fertile ground for artists. Institutions like the National Academy of Design were pivotal in shaping the American art scene, offering exhibition opportunities and fostering a community of artists. It was within this environment that Lacroix would begin to hone his craft and make his mark.

Emergence as a Still Life Painter

Paul Lacroix’s formal introduction to the New York art world as an exhibitor occurred in 1863. In this year, he presented his still life compositions at the prestigious National Academy of Design. Founded in 1825 by prominent artists such as Samuel F.B. Morse, Thomas Cole, and Asher B. Durand, the National Academy was instrumental in promoting American art and artists. Its annual exhibitions were highly anticipated events, providing a crucial platform for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and engage with their peers.

For Lacroix to exhibit at the National Academy was a significant step, indicating a certain level of skill and acceptance within the artistic community. From this debut in 1863, he became a consistent exhibitor at the Academy for the remainder of his relatively short life. His dedication to the still life genre was unwavering, and his works became a regular feature in these important annual showcases, allowing his style and reputation to grow. Beyond the National Academy, Lacroix's paintings also found their way into other exhibition venues, including the Brooklyn Art Museum, further solidifying his presence in the regional art scene.

Artistic Style: Precision, Detail, and the "Truth to Nature"

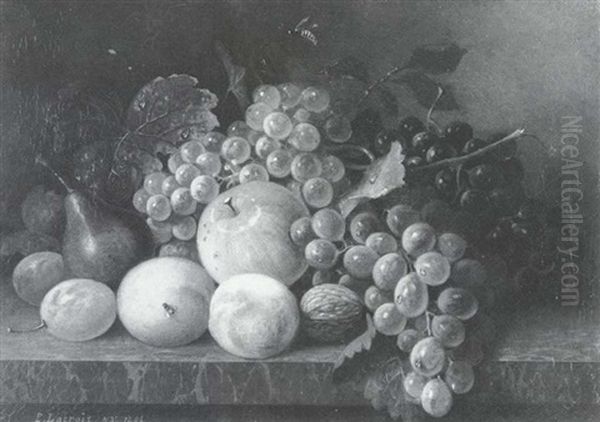

Paul Lacroix’s artistic output is characterized primarily by his dedication to still life, with a particular focus on fruits and flowers. His stylistic development shows an interesting trajectory. His earlier works are often described as possessing a certain simplicity and a rigorous, almost austere, quality in their linear definition. The forms are clearly delineated, and the compositions, while elegant, tend towards a more straightforward presentation.

As his career progressed, particularly into the later 1860s, Lacroix's style evolved towards greater complexity and ambition. His brushwork became more confident, and his compositions grew bolder and more elaborate. He demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture the intricate geometric structures of flowers and the varied textures of fruits. There is a palpable sense of the artist delighting in the visual and tactile qualities of his subjects – the velvety skin of a peach, the translucent gleam of grapes, the delicate unfurling of a rose petal.

A significant influence on Lacroix, and indeed on many artists of his generation, was the English art critic John Ruskin. Ruskin’s famous dictum to artists was to go to nature "rejecting nothing, selecting nothing, and scorning nothing," emphasizing a "truth to nature." This principle resonated deeply with the pre-Raphaelite movement in Britain and had a considerable impact on American artists as well. Lacroix’s commitment to rendering his subjects with fidelity, placing ordinary flowers and fruits on simple tabletops or in naturalistic settings, reflects this Ruskinian ideal. He sought to convey the inherent beauty of these natural forms without excessive idealization, allowing their intrinsic qualities to speak for themselves.

Influences and Comparisons: Chardin and Roesen

While Ruskin provided a philosophical underpinning, Lacroix's visual style also shows affinities with, and likely influence from, established masters of still life. One such figure is the 18th-century French painter Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin. Chardin was renowned for his quiet, intimate still lifes and genre scenes, celebrated for their subtle harmonies of color, masterful handling of light, and profound sense of order and tranquility. Lacroix’s careful attention to composition, the tactile rendering of surfaces, and the play of light on objects may echo Chardin's enduring legacy.

Perhaps a more direct and frequently cited comparison is with the German-born American painter Severin Roesen (c. 1815 – c. 1872). Roesen was a contemporary of Lacroix and a prolific painter of lush, abundant fruit and flower still lifes in the mid-19th century, working primarily in Pennsylvania. Roesen’s style, itself derived from the 17th-century Dutch still life tradition, was characterized by its opulence, vibrant color, and meticulous detail. Art historians often note similarities between Lacroix's and Roesen's work, particularly in the arrangement of fruit, the depiction of dewdrops, and the overall sense of profusion. It is plausible that Lacroix was familiar with Roesen's popular compositions and may have drawn inspiration from his approach to creating visually rich and appealing still lifes. Both artists contributed significantly to the popularity of this genre in America, catering to a growing middle-class desire for art that celebrated domesticity and nature's bounty.

Representative Works: Celebrating Nature's Abundance

Among Paul Lacroix's known works, several stand out as exemplars of his style and thematic concerns. Titles like The Abundance of Summer and Still Life with Grapes and Watermelon are indicative of his focus. These paintings typically feature carefully arranged assortments of fruits, often spilling from baskets or bowls, set against dark, neutral backgrounds that allow the vibrant colors and textures of the subjects to take prominence.

In The Abundance of Summer, one can imagine a composition teeming with the ripe fruits of the season – peaches, plums, berries, and perhaps a melon, all rendered with Lacroix’s characteristic attention to detail. The title itself evokes a sense of plenitude and the fleeting beauty of summer's harvest. Such works would have appealed to Victorian sensibilities, symbolizing prosperity, the bounty of nature, and the comforts of home.

Still Life with Grapes and Watermelon would similarly highlight Lacroix’s skill in capturing different textures and forms. The smooth, taut skin of grapes, often depicted with a delicate bloom or glistening highlights, contrasted with the rough rind and juicy, vibrant flesh of a cut watermelon, would offer a rich visual experience. These paintings were not merely decorative; they were celebrations of the natural world, meticulously observed and translated onto canvas with considerable technical skill. His ability to render the geometric complexity of flower petals and the intricate veining of leaves further attests to his keen observational powers.

The American School of Still Life Painting

Paul Lacroix is considered an important representative of the American school of still life painting in the mid-19th century. This tradition had its roots in the work of colonial-era painters and was significantly advanced by artists like the Peale family of Philadelphia, particularly Raphaelle Peale, in the early 19th century. By Lacroix's time, still life painting had become a well-established genre, popular with patrons and appreciated for its technical demands and aesthetic appeal.

Artists like Lacroix, Roesen, George Henry Hall, and John F. Francis were key figures in this mid-century flourishing. They often depicted abundant displays of fruit and flowers, sometimes in outdoor settings, sometimes on tabletops, reflecting a Victorian era fascination with nature, horticulture, and the cataloging of natural specimens. While the grand landscapes of the Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole, Asher B. Durand, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt, and Sanford Robinson Gifford captured the sublime majesty of the American wilderness, still life painters like Lacroix offered a more intimate, domesticated vision of nature's beauty. Their work complemented the grander narratives of landscape art, providing a different but equally valid perspective on the American experience and its relationship with the natural world. Martin Johnson Heade, though also known for landscapes and "luminist" works, also produced exquisite still lifes, particularly of orchids and hummingbirds, showcasing the diversity within the genre.

Life in an Artists' Community: Hoboken

Towards the end of his life, from approximately 1867 to 1869, Paul Lacroix resided in Hoboken, New Jersey. Situated just across the Hudson River from New York City, Hoboken in this period was developing into a community that attracted artists. Its proximity to the artistic and commercial center of New York, combined with potentially more affordable living and studio spaces, made it an appealing location.

Living in such a community would have offered Lacroix opportunities for interaction with fellow artists, fostering an environment of shared ideas and mutual support. While specific records of his interactions with other Hoboken artists are not extensively detailed, the nature of such communities often leads to informal exchanges and a collective artistic energy. This period in Hoboken marks the final years of his career.

A Brief but Significant Career

Paul Lacroix’s career, though impactful, was relatively short. He passed away in 1869 at the age of just 42. Despite his premature death, he had established himself as a skilled and respected painter of still lifes. His consistent presence at the National Academy of Design exhibitions for nearly a decade ensured that his work was seen and appreciated by a significant audience.

His paintings are valued for their technical proficiency, their adherence to the "truth to nature" ideal, and their contribution to the American still life tradition. They reflect a particular moment in American cultural history, an era of growing prosperity and a burgeoning appreciation for art that celebrated the beauty of the everyday and the natural world. His works can be found in various museum collections, allowing contemporary audiences to appreciate his contribution to 19th-century American art.

The legacy of painters like Lacroix is important for understanding the full spectrum of American art during this formative period. While grand historical narratives and epic landscapes often dominate art historical discussions, the quieter, more intimate genre of still life provided a vital counterpoint, reflecting different aspects of American life and values. Lacroix’s dedication to this genre, his evolving style, and his skillful renderings of nature's bounty secure his place within this important tradition.

The Enduring Appeal of Lacroix's Still Lifes

The enduring appeal of Paul Lacroix's still lifes lies in their meticulous beauty and their quiet celebration of the natural world. In an age increasingly dominated by rapid technological change and fleeting digital images, the tangible, carefully observed reality presented in Lacroix's paintings offers a moment of pause and contemplation. His work invites viewers to appreciate the simple elegance of fruit and flowers, rendered with a skill that makes them almost palpable.

His paintings serve as a window into the aesthetic sensibilities of the mid-19th century, an era that found profound beauty in the detailed representation of nature. The precision of his brushwork, the richness of his colors, and the harmony of his compositions speak to a deep respect for his subjects and a mastery of his craft. While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of some of his landscape-painting contemporaries, Paul Lacroix’s contribution to American art, particularly within the specialized and demanding genre of still life, remains significant and worthy of continued appreciation. His legacy is a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the beauty of the world around us, one carefully rendered fruit and flower at a time. His work, alongside that of artists like Severin Roesen, John William Hill (another Ruskin enthusiast), and the earlier masters like Chardin, continues to inform our understanding of the rich tapestry of 19th-century art.