Gabriel Metsu stands as one of the most accomplished and engaging painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Active during the vibrant 17th century, Metsu navigated the artistic currents of Leiden and Amsterdam, developing a remarkably versatile style that encompassed intimate genre scenes, bustling markets, historical narratives, and sensitive portraits. Though his career was relatively brief, spanning roughly two decades, his output was significant, and his reputation during his lifetime and in the century following his death placed him among the era's elite artists. His work is characterized by technical brilliance, psychological insight, and a keen observation of the textures, light, and social nuances of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Leiden

Gabriel Metsu was born in Leiden in January 1629. While the exact date is debated among scholars, baptismal records often point towards this period, with January 26th being a frequently cited date. He hailed from an artistic background; his father, Jaques Metsu, was a painter and tapestry designer originally from the Southern Netherlands. However, Jaques died relatively early in Gabriel's life, and the young artist was raised by his mother and stepfather. Leiden, at this time, was a major center for art, particularly known for the highly detailed style of the fijnschilders (fine painters).

Evidence regarding Metsu's formal training is scarce. While no definitive apprenticeship documents survive, the influence of several key figures is evident in his early work. Most prominently, Gerard Dou, the leading figure of the Leiden school and a former pupil of Rembrandt, seems to have left a mark. Metsu absorbed the fijnschilder emphasis on meticulous detail, smooth finish, and the careful rendering of textures, although his brushwork often retained a slightly greater fluidity than Dou's. Metsu was among the founding members of the Leiden Guild of Saint Luke in 1648, indicating his early establishment as an independent master.

During his Leiden years, Metsu also appears to have absorbed influences from artists beyond the immediate fijnschilder circle. Connections have been drawn to painters associated with Utrecht, such as Nicolaes Knupfer and Jan Baptist Weenix. These artists often tackled historical and biblical subjects with a somewhat broader, more narrative approach, and elements of this can be seen in some of Metsu's earlier, more complex figure compositions. His work from this period demonstrates a willingness to experiment with different themes and stylistic approaches, laying the groundwork for his later versatility.

Another significant Leiden contemporary was Jan Steen, known for his lively, often humorous, and moralizing genre scenes. While their styles differed in finish – Steen's being generally looser – they shared an interest in depicting everyday life, taverns, and domestic interiors. It is likely they knew each other, possibly interacting within the Guild, and a certain shared sensibility in capturing human interactions can sometimes be discerned. Frans van Mieris the Elder, another prominent Leiden fijnschilder slightly younger than Metsu, also rose to prominence during this period, further enriching the city's artistic milieu.

Move to Amsterdam and Mature Style

Around 1657, Gabriel Metsu relocated to Amsterdam, the bustling commercial and cultural heart of the Dutch Republic. This move marked a significant turning point in his career and artistic development. Amsterdam offered a larger, wealthier clientele and a different artistic environment, less dominated by the Leiden fijnschilder tradition and more exposed to the broader currents of Dutch painting, including the lingering influence of Rembrandt and the burgeoning market for elegant genre scenes.

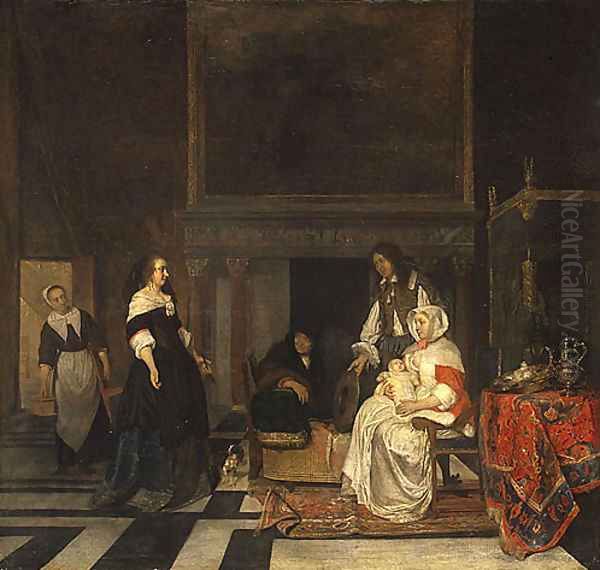

In Amsterdam, Metsu's style evolved towards greater refinement and elegance. He increasingly focused on depicting the comfortable interiors and leisured activities of the affluent merchant class. His brushwork became smoother, his rendering of luxurious fabrics like silk, satin, and velvet reached new heights of verisimilitude, and his compositions often acquired a greater sense of calm and order. This shift reflects not only changing artistic influences but also the demands of the Amsterdam market, which favored scenes of domestic harmony, courtship, and quiet contemplation.

The influence of artists like Gerard ter Borch becomes particularly apparent during Metsu's Amsterdam period. Ter Borch, known for his supremely elegant depictions of upper-class life, excelled at rendering textures and capturing subtle psychological nuances in quiet interior scenes. Metsu adopted a similar focus on refined subjects and exquisite detail, particularly in his portrayal of satin dresses, a hallmark of Ter Borch's work. However, Metsu often imbued his scenes with a slightly warmer palette and a more accessible narrative quality.

Comparisons are also frequently made with Johannes Vermeer of Delft. While direct contact is unproven, the parallels in their work from the late 1650s and 1660s are striking. Both artists excelled at depicting tranquil domestic interiors illuminated by natural light, often featuring solitary female figures engaged in quiet activities like reading letters or making music. They shared a mastery of light, color harmony, and the creation of a palpable atmosphere. For a long time, particularly in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Metsu's reputation arguably overshadowed Vermeer's, and some of his works were even attributed to the Delft master after Vermeer's rediscovery.

During his time in Amsterdam, Metsu achieved considerable success. His paintings commanded high prices, and he was sought after by collectors. His personal life also saw changes; records indicate he married Isabella de Wolff in 1658. She came from a family with artistic connections – her mother was the painter Maria de Grebber. This marriage likely further integrated him into Amsterdam's artistic and social circles. Some scholars suggest Isabella may have served as a model for figures in his paintings. Earlier sources mention other potential marriages, but the union with Isabella de Wolff is the most clearly documented during his successful Amsterdam years.

Thematic Versatility: Beyond the Drawing Room

While Metsu is perhaps best known today for his elegant interior genre scenes, a defining characteristic of his oeuvre is its remarkable thematic range. Unlike specialists such as Willem Kalf (still life) or Philips Wouwerman (battle scenes), Metsu moved fluidly between different types of painting, demonstrating proficiency in multiple areas. This versatility catered to a broad market and showcased the breadth of his technical skill and observational powers.

His interior scenes remain central to his legacy. Works like Man Writing a Letter and its pendant Woman Reading a Letter (both c. 1664-1666, National Gallery of Ireland) exemplify his mature Amsterdam style. These paintings depict quiet moments of private communication within well-appointed rooms, rendered with exquisite attention to detail – the textures of clothing, the play of light on objects, the subtle expressions of the figures. The Music Lesson (National Gallery, London) presents a similarly elegant scene of courtship and refinement, rich in symbolic detail and demonstrating his mastery of complex spatial arrangements.

However, Metsu also frequently depicted less rarefied environments. His market scenes, such as the Vegetable Market in Amsterdam (Louvre, Paris), are vibrant compositions teeming with life. They capture the hustle and bustle of public commerce, showcasing a diverse array of figures – vendors, shoppers, children, animals – rendered with lively characterization. These works reveal a different facet of Metsu's talent: his ability to organize complex multi-figure compositions and capture the energy of urban life. Tavern scenes and depictions of blacksmith shops also feature in his work, demonstrating an interest in the activities of artisans and the lower strata of society.

Metsu did not entirely abandon historical and biblical subjects after moving to Amsterdam. Though less frequent than his genre paintings, works like Christ and the Adulteress (Louvre, Paris) show his continued engagement with narrative painting on a grander scale. This particular work reveals the lingering influence of Rembrandt's circle in its dramatic lighting (chiaroscuro) and emotional intensity. He also painted allegorical subjects and occasional portraits, further demonstrating his adaptability.

Elements of still life are prominent throughout Metsu's work, often integrated seamlessly into his genre scenes. He rendered objects – musical instruments, tableware, textiles, food items – with the same meticulous attention to texture and light that he applied to his figures. These still-life elements not only add to the realism and richness of the scene but often carry symbolic weight, contributing to the painting's narrative or theme. His skill in this area rivals that of dedicated still-life painters of the period.

Artistic Style and Technical Mastery

Gabriel Metsu's art is defined by a combination of technical virtuosity, keen observation, and narrative skill. His ability to render textures was exceptional. Whether depicting the shimmering highlights on silk, the soft pile of an oriental carpet, the rough weave of a peasant's tunic, or the cool gleam of metal, Metsu conveyed the material qualities of objects with uncanny realism. This tactile quality invites the viewer into the painted world, enhancing the sense of presence and intimacy.

His handling of light and color is equally masterful. Often employing a primary light source from a window to the side, typical of Dutch interior painting, Metsu modulated light and shadow to define form, create atmosphere, and direct the viewer's attention. His palette could range from the bright, clear colors seen in some market scenes to the more subdued, harmonious tones of his elegant interiors. He understood how light interacted with different surfaces and used this knowledge to create scenes of remarkable luminosity and depth.

Compositionally, Metsu arranged his scenes with care, balancing figures and objects within believable spatial settings. He often used framing devices, like doorways or curtains, to enhance the sense of looking into a private space. His perspective is generally convincing, contributing to the illusion of reality. While his compositions are typically well-ordered, they often retain a sense of naturalness, avoiding rigid formality.

Beyond technical skill, Metsu was a gifted storyteller. His genre scenes are rarely mere depictions of activities; they often imply a narrative, hint at relationships between figures, or explore themes of love, domesticity, virtue, or temptation. He conveyed emotions and psychological states through subtle gestures, facial expressions, and the careful arrangement of figures and symbolic objects. This narrative richness engages the viewer, inviting interpretation and contemplation. Compared to Vermeer's often enigmatic stillness, Metsu's narratives tend to be more explicit, though still handled with delicacy. In contrast to Jan Steen's often boisterous and overtly moralizing scenes, Metsu's approach is generally more restrained and observational.

His brushwork adapted to his subject matter. While capable of the highly polished finish associated with the Leiden fijnschilders, particularly in his later Amsterdam works, he could also employ looser, more visible brushstrokes when depicting rougher textures or suggesting movement, especially in his earlier pieces or outdoor scenes. This adaptability underscores his technical command and his focus on achieving the appropriate effect for each specific subject.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as quintessential examples of Gabriel Metsu's artistry and are central to understanding his contribution to Dutch art.

Man Writing a Letter and Woman Reading a Letter (c. 1664-1666, National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin): This pair is often considered the pinnacle of Metsu's mature Amsterdam style. The paintings depict a wealthy couple engaged in correspondence, separated physically but connected by the letters. The meticulous rendering of fabrics (the man's Persian silk robe, the woman's yellow silk jacket trimmed with ermine), the intricate still-life details (silver inkstand, Turkish carpet, seascape painting), and the subtle play of light create an atmosphere of quiet intimacy and luxury. The narrative hints at courtship or private communication, handled with characteristic sensitivity.

The Sick Child (c. 1664-1666, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam): This painting is remarkable for its emotional tenderness. A mother holds her listless child, gazing at it with concern. The muted colors, soft lighting, and the mother's gentle expression convey a profound sense of parental love and anxiety. The work departs from Metsu's more typical scenes of elegant leisure, showcasing his ability to handle themes of universal human experience with empathy and restraint. Its emotional depth has led some scholars to draw parallels with religious imagery, particularly the Pieta.

The Music Lesson (c. 1658-1661, National Gallery, London): An earlier example of his Amsterdam interior scenes, this painting depicts a woman at a virginal and a man standing beside her, presumably her tutor or suitor. The composition is rich in detail, including a cello, a Turkish carpet, and paintings on the wall. Music-making was a common theme in Dutch art, often associated with love and harmony. Metsu captures the elegance of the setting and the ambiguous relationship between the figures with characteristic skill.

Vegetable Market in Amsterdam (c. 1660-1661, Louvre, Paris): This work showcases Metsu's ability to handle complex, bustling outdoor scenes. It presents a vibrant cross-section of Amsterdam life, filled with vendors selling their wares, shoppers inspecting produce, and various figures interacting. The lively characterizations, detailed rendering of goods, and dynamic composition make it a compelling depiction of 17th-century urban commerce. It contrasts sharply with the quietude of his interior scenes, highlighting his versatility.

Christ and the Adulteress (1653, Louvre, Paris): An important example of his earlier work, likely painted during his Leiden period or shortly after. This biblical scene demonstrates his ambition in tackling historical subjects. The dramatic lighting, reminiscent of Rembrandt's circle, focuses attention on Christ and the accused woman. The varied reactions of the surrounding figures add to the narrative intensity. It shows a different, more overtly dramatic side of Metsu's art compared to his later genre paintings.

Contemporaries and Artistic Dialogue

Gabriel Metsu did not work in isolation. He was part of a rich network of artists, and his work reflects an ongoing dialogue with his contemporaries and predecessors. His relationship with Gerard Dou in Leiden was foundational, establishing a basis in meticulous technique. His interactions or shared milieu with Jan Steen likely influenced his interest in genre themes and narrative detail, though their approaches diverged. Frans van Mieris the Elder, another Leiden star, shared Metsu's dedication to fine painting and elegant subjects.

In Amsterdam, the influence of Gerard ter Borch is undeniable, particularly in the adoption of refined subjects, elegant attire (especially satin), and subtle psychological portrayal. The parallels with Johannes Vermeer, though perhaps indirect, are significant, suggesting shared interests in light, domesticity, and quietude that were current in Dutch art of the period. Pieter de Hooch, another painter of luminous interiors and courtyards, active in Delft and later Amsterdam, explored similar themes of domestic life, though often with a greater emphasis on geometric structure and spatial clarity.

While Metsu moved away from the overt drama of Rembrandt's history paintings, the elder master's pervasive influence on Dutch art, particularly in the handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and emotional depth, can still be felt in some of Metsu's works, like Christ and the Adulteress or The Sick Child. Other Amsterdam contemporaries included figure painters like Ferdinand Bol and Govaert Flinck, both former Rembrandt pupils who developed successful careers. Metsu's ability to carve out a distinct and highly successful niche amidst such talent speaks to his unique skills and adaptability. His work, in turn, likely influenced younger painters specializing in genre scenes, such as Jacob Ochtervelt and Eglon van der Neer.

The anecdote, recounted by the early art biographer Arnold Houbraken, about Metsu being accused by a neighbor of stealing chickens in Leiden, while perhaps embellished, paints a picture of a young artist possibly living a somewhat bohemian life before achieving major success. His documented marriage to Isabella de Wolff in Amsterdam suggests a more settled and prosperous existence later on. The occasional variation in his signature (sometimes adding an extra 'E' – "G. Metsue") is a minor curiosity noted by scholars, possibly reflecting variations in contemporary spelling or a personal quirk.

Legacy and Shifting Reputation

Gabriel Metsu died relatively young, in October 1667, and was buried in Amsterdam's Nieuwe Kerk on October 24th. He was only 38 years old but had already produced a substantial and highly regarded body of work. In the decades following his death, and throughout the 18th century, his reputation remained exceptionally high. His paintings were eagerly sought after by prominent collectors across Europe, including the Electors of Saxony and figures who acquired works now in major collections like the Wallace Collection in London. His prices at auction often rivaled or exceeded those of almost any other Dutch master, including Rembrandt and, at that time, the largely forgotten Vermeer.

His popularity stemmed from the appealing nature of his subjects, his dazzling technique, and the narrative charm of his scenes. The elegance, refinement, and meticulous finish of his Amsterdam-period works resonated particularly well with 18th-century Rococo tastes. He was praised for his versatility and his ability to capture the spirit of Dutch life with both realism and grace.

The 19th century witnessed a gradual shift in artistic taste and art historical focus. The "rediscovery" of Johannes Vermeer, championed by critics like Théophile Thoré-Bürger in the 1860s, led to a dramatic reappraisal of Vermeer's genius. As Vermeer's star ascended, Metsu's, while still respected, began to be somewhat overshadowed. Vermeer came to be seen as the supreme poet of light and quietude, and Metsu, despite the similarities in some works, was sometimes viewed as perhaps more anecdotal or less profound. His very versatility, once a key strength, perhaps counted against him in an era that increasingly valued perceived specialization and unique artistic vision.

Despite this relative decline from the pinnacle he occupied in the 18th century, Metsu never fell into obscurity. His works remained prized possessions in major museums and private collections. However, he received less focused scholarly attention compared to figures like Rembrandt, Hals, or Vermeer for much of the 20th century.

The early 21st century has seen a significant resurgence of interest in Gabriel Metsu. Major retrospective exhibitions, notably one organized collaboratively by the National Gallery of Ireland, the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, and the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. (2010-2011), brought his work back into the spotlight. These exhibitions allowed for a comprehensive reassessment of his career, highlighting his technical brilliance, his thematic range, and his crucial role within the network of Dutch Golden Age painters. Contemporary scholarship now recognizes him not merely as a follower of trends but as an innovative and highly influential artist in his own right, a master storyteller whose works offer captivating glimpses into 17th-century Dutch life.

Conclusion: An Enduring Master

Gabriel Metsu remains a pivotal figure in the study of Dutch Golden Age art. His journey from Leiden to Amsterdam mirrors the broader shifts within Dutch painting, moving from the detailed precision of the fijnschilders towards the elegant genre scenes favored by the wealthy urban elite. His remarkable versatility allowed him to excel in various genres, capturing everything from the quiet intimacy of domestic interiors to the vibrant energy of public markets and the drama of historical narratives.

His technical mastery, particularly in rendering textures and the effects of light, places him among the most skilled painters of his era. Beyond mere technique, his works possess a narrative charm and psychological insight that continue to engage viewers today. While his reputation has fluctuated over the centuries, overshadowed at times by the singular genius of Vermeer, modern reassessments have reaffirmed his status as a major master. Gabriel Metsu's paintings offer a rich, detailed, and often beautiful window onto the world of the Dutch Republic, securing his enduring importance in the history of art.