Gaetano Mormile (1839-1890) was an Italian painter active during a vibrant period of artistic transformation in Naples and across Italy. While detailed biographical information about Mormile remains somewhat elusive, his attributed works and stylistic characteristics place him within the rich tapestry of 19th-century Neapolitan art, a school known for its dynamic engagement with tradition and modernity. This exploration seeks to situate Mormile within his artistic environment, examining his known contributions and the broader currents that shaped painters of his era.

The Artistic Landscape of 19th-Century Naples

Naples in the 19th century was a bustling metropolis and a significant artistic hub, second only to Paris in population for a time and boasting a long, distinguished artistic heritage. The Royal Academy of Fine Arts (Reale Accademia di Belle Arti) was a central institution, yet the period also saw artists exploring new paths beyond strict academicism. The city's unique light, its vibrant street life, and the dramatic beauty of its surrounding landscapes provided endless inspiration.

Artists in Naples during Mormile's lifetime were navigating a complex interplay of influences. The legacy of the great Neapolitan Baroque masters, such as Luca Giordano (1634-1705) and Francesco Solimena (1657-1747), still resonated, particularly in their dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and dynamic compositions. Concurrently, European Romanticism had taken firm root, emphasizing emotion, individualism, and often a deep connection to local culture and history. Furthermore, a growing interest in realism and verismo encouraged artists to depict everyday life and contemporary social conditions with unflinching honesty.

Gaetano Mormile: Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born in 1839, Gaetano Mormile's career unfolded during the latter half of the 19th century, a period that witnessed the unification of Italy (the Risorgimento) and significant social and cultural shifts. While specifics of his training are not extensively documented, it is probable that he received instruction within the Neapolitan academic system or through apprenticeship with established masters, as was common. Artists of his generation would have been exposed to a curriculum that emphasized drawing from casts and life, perspective, and the study of Old Masters.

The limited available information suggests Mormile was a painter who worked primarily in oils. His style is described as being rooted in 19th-century Italian Romanticism, yet also drawing upon the decorative elegance of Rococo and the compositional strength of the Baroque. This fusion indicates an artist who, while contemporary in sentiment, respected and reinterpreted historical artistic languages. Characteristics attributed to his work include delicate brushwork and a rich color palette, suggesting a concern for both refined execution and visual appeal.

The Neapolitan School and Mormile's Contemporaries

To understand Mormile better, it is essential to consider the broader Neapolitan School of painting in the 19th century. This was not a monolithic entity but rather a constellation of artists with diverse approaches. The Posillipo School, flourishing in the earlier part of the century with figures like Anton Sminck van Pitloo and his student Giacinto Gigante (1806-1876), had already established a strong tradition of landscape painting, capturing the luminous atmosphere of the Bay of Naples.

Later in the century, artists like Domenico Morelli (1826-1901) became leading figures. Morelli was influential as both a painter and a teacher at the Academy. He moved from historical Romanticism towards a more Symbolist and Orientalist vein, known for his dramatic historical and religious scenes, often imbued with a sense of psychological intensity. His work, characterized by rich textures and a vibrant palette, had a profound impact on a generation of Neapolitan painters.

Filippo Palizzi (1818-1899) was another key artist, known for his meticulous realism, particularly in his depictions of animals and rural life. He, along with his brothers Giuseppe, Nicola, and Francesco Paolo, emphasized direct observation from nature. Filippo's commitment to verismo offered a counterpoint to Morelli's more romantic or historical leanings.

Other notable contemporaries included Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884), who, although spending much of his career in Paris and London, retained a Neapolitan sensibility. He became renowned for his elegant depictions of modern urban life, capturing fleeting moments with a sophisticated, almost Impressionistic touch. His international success brought prestige to Italian art of the period.

Antonio Mancini (1852-1930), a student of Morelli and Palizzi, developed a highly individualistic style characterized by thick impasto and a vibrant, almost sculptural use of paint. His portraits and genre scenes, often depicting circus performers or working-class figures, are remarkable for their expressive power and innovative technique.

Francesco Paolo Michetti (1851-1929), from the nearby Abruzzo region but closely linked to Neapolitan artistic circles, was celebrated for his large-scale, vibrant depictions of local peasant life, festivals, and traditions. His work often combined ethnographic detail with a powerful, almost photographic realism, sometimes verging on the monumental.

Gioacchino Toma (1836-1891), a contemporary of Mormile, was known for his poignant and often melancholic interior scenes, depicting domestic life with a quiet intimacy and psychological depth. His works often carried subtle social commentary, reflecting the hardships and resilience of ordinary people.

These artists, among many others, created a dynamic and multifaceted artistic environment. They engaged with international trends like Realism and, later, Impressionism, while also exploring uniquely Italian and Neapolitan themes. The influence of photography was also beginning to be felt, impacting artists' approaches to composition and representation.

Mormile's Known Work: "Basse cour"

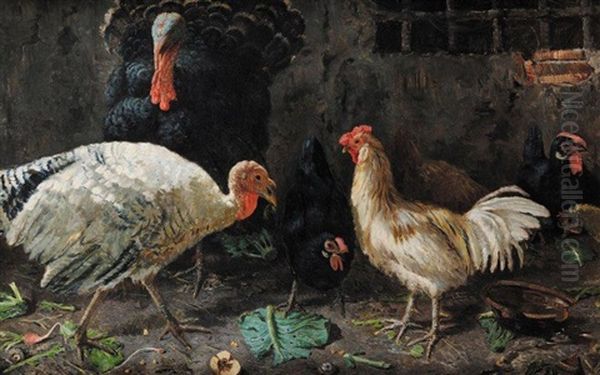

One of the few specifically identified works by Gaetano Mormile is an oil painting titled "Basse cour" (Farmyard or Lower Courtyard). This painting, measuring 88.5 x 142 cm and signed by the artist in the lower right, is dated to the 19th century. Its subject matter, a farmyard scene, aligns with the 19th-century taste for genre painting – depictions of everyday life and rural settings. Such scenes were popular across Europe, offering a sense of rustic charm or, at times, a more realistic portrayal of agricultural life.

The description of "Basse cour" as exhibiting Baroque compositional elements suggests a structured and perhaps dynamic arrangement of figures and forms within the pictorial space. The influence of Baroque art could manifest in strong diagonal lines, a sense of depth, and a lively interplay of light and shadow, even within a seemingly humble genre scene. The fact that this painting has appeared at auction, with an estimated value of €2700 to €3000 at one point, indicates a degree of market recognition for Mormile's work, at least within specialized collecting circles.

The choice of a "Basse cour" subject places Mormile in the company of artists like Filippo Palizzi, who excelled in rendering animals and rural environments with great fidelity. However, Mormile's purported blend of Romanticism with Baroque and Rococo influences might have resulted in a treatment that was less strictly veristic than Palizzi's, perhaps imbuing the scene with a more picturesque or emotionally resonant quality.

Stylistic Threads: Baroque, Rococo, and Romanticism

The assertion that Mormile's art was influenced by Baroque and Rococo traditions, alongside 19th-century Romanticism, points to a complex stylistic profile. The Baroque legacy in Naples was profound, characterized by dynamism, emotional intensity, and often dramatic lighting. If Mormile drew from this, his works might feature strong compositions, a rich, often dark palette, and a sense of movement or theatricality.

The Rococo influence, typically associated with the 18th century, suggests an appreciation for elegance, lighter palettes, curvilinear forms, and often intimate or charming subject matter. A Rococo sensibility in a 19th-century context might translate into a refinement of touch, a decorative quality, and a focus on the graceful aspects of a scene. The "delicate brushwork" attributed to Mormile could align with this.

Romanticism, the dominant artistic and intellectual movement of the early to mid-19th century, emphasized emotion, individualism, the sublime power of nature, and often a fascination with history and folklore. In Italy, Romanticism also intertwined with the nationalist sentiments of the Risorgimento. For a painter like Mormile, Romanticism could manifest in the choice of evocative subjects, an attempt to capture a particular mood or atmosphere, or a more personal and expressive approach to painting.

The interplay of these stylistic threads suggests that Mormile was not a strict adherent to any single dogma but rather an artist who selectively drew from various traditions to forge his own visual language. This eclecticism was not uncommon in the 19th century, as artists grappled with a rich historical inheritance while seeking new forms of expression.

Religious Themes and Commissions

Beyond genre scenes like "Basse cour," there are indications that Gaetano Mormile may have also undertaken religious commissions. The source material mentions the possibility of him creating multi-panel paintings for religious institutions in Naples, such as a Dominican convent, with these works also reflecting Baroque artistic characteristics. Naples has a vast number of historic churches and convents, many of which continued to commission art throughout the 19th century.

If Mormile engaged in religious painting, he would have been working within a long and venerable tradition. Subjects such as the Madonna and Child, scenes from the lives of saints, or altarpieces would have been common. A Baroque influence in such works would likely translate into dramatic compositions, fervent emotional expression, and rich, symbolic use of color and light, echoing the grand manner of earlier Neapolitan masters. This would contrast with, yet complement, the more intimate scale of a genre painting like "Basse cour."

The ability to work across different genres, from everyday scenes to sacred art, would demonstrate versatility. Many 19th-century artists, particularly those with academic training, were expected to be proficient in various types of painting, including historical, religious, portrait, and genre subjects.

Broader Italian Artistic Context: The Macchiaioli and Verismo

While Mormile was primarily a Neapolitan painter, it's useful to consider the wider Italian artistic landscape. In Tuscany, the Macchiaioli movement emerged around the mid-19th century, with artists like Giovanni Fattori (1825-1908), Silvestro Lega (1826-1895), and Telemaco Signorini (1835-1901). They advocated for painting outdoors (en plein air) and used "macchie" (patches or spots of color) to capture the effects of light and shadow, often focusing on scenes of contemporary Italian life, landscapes, and military subjects related to the Risorgimento. While distinct from the Neapolitan school, the Macchiaioli represented a significant push towards modernism in Italian art.

The broader trend of Verismo (Realism) in Italian art and literature also gained traction in the latter half of the 19th century. This movement sought to depict life with truthfulness and objectivity, often focusing on the lives of ordinary people, including peasants and the urban poor. Artists like Palizzi in Naples, and others throughout Italy, contributed to this current. If Mormile's "Basse cour" leaned towards a realistic depiction of a farmyard, it would align with this Verist impulse.

The preeminent Italian Romantic painter, Francesco Hayez (1791-1882), though based in Milan, set a standard for historical Romanticism with his large-scale paintings, often depicting medieval or Renaissance subjects imbued with patriotic undertones. His influence was felt across Italy, shaping the public's and artists' expectations for grand historical narratives.

Mormile's Potential Legacy and Challenges in Assessment

Assessing Gaetano Mormile's precise historical standing presents challenges due to the relative scarcity of comprehensive scholarly research dedicated solely to him. He appears to be one of many talented artists active in a fertile period, whose individual contributions can sometimes be overshadowed by more famous contemporaries or by the sheer volume of artistic production.

However, the existence of signed works like "Basse cour" and their appearance in the art market confirm his activity and a degree of contemporary or subsequent appreciation. His stylistic blend, drawing from the rich heritage of Neapolitan Baroque and Rococo while engaging with 19th-century Romanticism, suggests an artist who was both historically aware and responsive to the aesthetic currents of his own time.

Further research, including the potential discovery and attribution of more works, could illuminate his oeuvre more fully. Examining his paintings in detail, comparing them with those of his Neapolitan contemporaries, and searching for mentions in period exhibition records or art criticism could provide a clearer picture of his career, his thematic concerns, and his reception.

The artists of 19th-century Naples, including figures like Mormile, contributed to a vibrant chapter in Italian art history. They navigated the transition from deeply entrenched academic traditions to more modern modes of expression, reflecting the changing social, political, and cultural landscape of their time. Their work often reveals a deep love for their region, its people, and its unique atmosphere, while also engaging with broader European artistic dialogues.

Conclusion: An Artist of His Time and Place

Gaetano Mormile (1839-1890) emerges as a representative of the Neapolitan school of painting in the latter half of the 19th century. While not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like Domenico Morelli or Antonio Mancini, his work, exemplified by pieces such as "Basse cour," demonstrates a skillful engagement with genre subjects and a stylistic approach that synthesized Romantic sensibilities with enduring influences from the Baroque and Rococo periods.

His activity in Naples placed him at the heart of a dynamic artistic milieu, where traditions were honored yet also reinterpreted in light of new ideas about realism, emotional expression, and the role of art in society. Whether depicting humble farmyard scenes or potentially more elevated religious subjects, Mormile likely contributed to the rich visual culture of his city.

The study of artists like Gaetano Mormile is crucial for a nuanced understanding of 19th-century Italian art. It moves beyond the handful of celebrated masters to appreciate the broader spectrum of talent and the diverse artistic practices that characterized the era. Each artist, through their unique vision and skill, added to the collective artistic heritage, reflecting the complexities and beauties of their world. Gaetano Mormile, as a painter of 19th-century Naples, remains a figure worthy of continued attention and appreciation within this historical context.