The annals of art history are rich with celebrated masters whose works adorn the world's most prestigious galleries and whose lives are meticulously documented. Yet, alongside these luminaries exist countless artists who, despite contributing to the cultural tapestry of their time, remain in relative obscurity. Georg Engelhardt, reportedly active as a painter between 1823 and 1883, appears to be one such figure from 19th-century Germany. Piecing together a comprehensive portrait of Engelhardt presents a fascinating challenge, relying on fragmented references and the broader context of the artistic milieu in which he presumably operated. This exploration seeks to shed light on his potential artistic journey, style, and the world that shaped him.

The 19th century was a period of profound transformation in Europe, and Germany was no exception. It was an era marked by political upheaval, industrial advancement, and a burgeoning national consciousness, all of which found expression in the arts. For a painter like Georg Engelhardt, whose life spanned a significant portion of this dynamic century, the artistic landscape would have been diverse and ever-evolving, offering a multitude of influences and paths.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Information regarding Georg Engelhardt's specific birthdate in 1823 and his early life remains elusive in detailed public records typically associated with prominent artists. However, if he pursued a career as a painter in Germany during this period, his artistic education would likely have followed certain conventional routes. Aspiring artists often began their training under a local master or at one of the burgeoning art academies in cities like Berlin, Munich, Dresden, or Düsseldorf. These institutions, while varying in their pedagogical approaches, generally emphasized rigorous training in drawing, anatomy, and perspective, often with a strong focus on classical ideals and historical subjects.

It is suggested that Engelhardt may have undertaken studies in both Germany and France. If this was the case, his exposure would have been significantly broadened. Germany, in the first half of the 19th century, was still heavily influenced by Romanticism, with artists like Caspar David Friedrich and Philipp Otto Runge exploring themes of nature, spirituality, and national identity. The Nazarene movement, which sought a revival of Christian art based on early Renaissance models, also held sway, with figures like Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius making significant contributions, particularly in fresco painting.

A period of study in France would have exposed Engelhardt to a different, yet equally vibrant, artistic environment. Paris was increasingly becoming the epicenter of the art world. Depending on when he might have studied there, he could have encountered the lingering influence of Neoclassicism, championed by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, or the dramatic fervor of Romanticism as exemplified by Eugène Delacroix. By the mid-century, Realism, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, was challenging academic conventions by depicting everyday life and ordinary people with unvarnished honesty.

This dual exposure, if indeed part of Engelhardt's journey, would have provided a rich tapestry of artistic philosophies and techniques. German art often carried a strong intellectual or spiritual undercurrent, while French art was perhaps more engaged with painterly qualities and contemporary social observation, especially as the century progressed.

Artistic Style and Potential Influences

Georg Engelhardt is described as an artist whose oeuvre included church paintings, allegorical scenes, historical subjects, and portraiture. This range suggests a versatile painter, comfortable across various genres that were popular and commissioned during the 19th century. His style is characterized by "fine details and balanced composition," attributes often associated with academic training. Such a description points towards a meticulous approach, where precision and harmonious arrangement were paramount.

The observation that his work, while technically proficient and balanced, sometimes "lacked innovation" is a common critique leveled at many academically trained artists of the period who adhered closely to established conventions. In an era that saw the rise of revolutionary movements like Impressionism, an artist maintaining a more traditional, detailed style might be perceived as less groundbreaking, yet still highly skilled and valued, particularly for official commissions, religious art, and portraiture.

The mention of French Impressionism as a potential influence is intriguing. If Engelhardt was active until 1883, he would have witnessed the emergence and development of this radical movement, which began to gain prominence in the 1860s and 1870s. Artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir were revolutionizing painting with their emphasis on capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light and color, and scenes of modern life, often painted en plein air. If Engelhardt was indeed influenced by Impressionism, it might have manifested in a lightening of his palette, a looser brushstroke in his later works, or a greater interest in contemporary subjects, though this would need to be substantiated by specific artworks.

Alternatively, he might have remained more aligned with the German artistic traditions. The Düsseldorf school of painting, for instance, was highly influential, known for its detailed and often narrative-driven historical and genre paintings. Artists like Carl Friedrich Lessing and Andreas Achenbach were prominent figures. In Munich, the Piloty School, led by Karl von Piloty, emphasized historical painting with a dramatic, realistic flair, influencing artists like Franz von Lenbach, who became a renowned portraitist, and Hans Makart, whose opulent style was immensely popular in Vienna.

Key Themes and Subjects in Engelhardt's Work

The reported thematic concerns of Georg Engelhardt – church paintings, allegories, historical subjects, and portraits – place him firmly within the mainstream of 19th-century artistic production. Each of these genres had a significant role and catered to different aspects of societal and cultural life.

Church paintings would have involved creating altarpieces, murals, or other devotional images for religious institutions. In 19th-century Germany, there was a continued demand for such art, fueled by both Catholic and Protestant communities. These works often depicted biblical scenes, lives of saints, or symbolic representations of Christian doctrine, requiring a style that was both inspiring and didactically clear. The Nazarene movement had already laid significant groundwork for a revival of religious art, emphasizing sincerity and spiritual depth.

Allegorical paintings, popular since the Renaissance, use symbolic figures and narratives to convey abstract concepts like justice, virtue, or historical events. These often required a strong understanding of classical mythology, history, and literature. Such works were favored for public buildings, academic institutions, and private collections of the educated elite. Artists like Anselm Feuerbach and Hans von Marées, though developing their own distinct classical styles, worked within this tradition of imbuing classical forms with profound meaning.

Historical subjects were a cornerstone of academic art in the 19th century. These paintings often depicted significant events from national or classical history, intended to edify, inspire patriotism, or provide moral lessons. The scale could be grand, and the compositions complex, demanding meticulous research into costumes, settings, and historical accuracy. Artists like Adolph Menzel in Germany became famous for their vivid and detailed portrayals of Prussian history.

Portraiture remained a consistently important genre, providing a livelihood for many artists. In an age before widespread photography, painted portraits were the primary means of preserving the likeness of individuals – from royalty and aristocracy to the burgeoning bourgeoisie, fellow artists, and family members. A successful portraitist needed not only technical skill in capturing a likeness but also the ability to convey the sitter's personality and status. The "fine details and balanced composition" attributed to Engelhardt would have served him well in this field.

Representative Works: A Matter of Attribution

Pinpointing specific, universally acknowledged painted masterpieces by Georg Engelhardt (1823-1883) is challenging based on readily available, consolidated art historical records. The information landscape can sometimes be fragmented for artists who did not achieve the highest echelons of fame or whose works are primarily in private collections or less-cataloged regional museums.

Interestingly, some historical records associate a Georg Engelhardt of a similar period with theological writings rather than paintings. For instance, works such as Der Seelkornlange nach den Evangelien dargestellt (1861) and Die Bergpredigt nach Matthäus (1864) are attributed to a Georg Engelhardt who was a professor of theology. This raises questions about potential confusion between individuals of the same name or if the painter also engaged in theological scholarship.

However, if we focus on the description of Georg Engelhardt as a painter of "church paintings, allegories, historical subjects, and portraits," his representative works would lie within these categories. Without specific titles, we can surmise the nature of such pieces:

Church Paintings: Perhaps an altarpiece depicting "The Sermon on the Mount" for a church in a significant German town, executed with clarity and devotional feeling, reflecting the stylistic preferences of the commissioning body. Or a series of murals illustrating scenes from the life of a patron saint.

Allegorical Works: A canvas titled "The Triumph of Germania" or "Industry and Art," personified by classical figures, destined for a civic building, showcasing his skill in complex compositions and symbolic representation.

Historical Subjects: A painting like "The Signing of the Peace of Westphalia" or a scene from the life of Frederick the Great, rendered with the detailed accuracy and dramatic narrative popular in historical genre painting of the time.

Portraits: Numerous likenesses of local dignitaries, merchants, and their families, characterized by their "fine details" in rendering attire and features, and "balanced compositions" that convey a sense of order and propriety.

The search for these specific painted works would require in-depth archival research, exploring regional museum catalogs, church records, and private collection histories in areas where Engelhardt might have been active.

The German Art Scene in the 19th Century: A Broader Context

To understand a figure like Georg Engelhardt, it's crucial to appreciate the dynamic artistic environment of 19th-century Germany. The century began with Romanticism, which emphasized emotion, individualism, and the sublime beauty of nature. Artists like Caspar David Friedrich created iconic landscapes imbued with spiritual and nationalistic sentiment. Simultaneously, the Nazarenes, based in Rome, sought to revive German religious art by emulating early Italian Renaissance masters.

As the century progressed, Realism gained traction. In Germany, this often took the form of detailed genre scenes, historical paintings, and portraits that aimed for accuracy and truthfulness. Adolph Menzel was a towering figure, known for his meticulous depictions of Prussian history and scenes of everyday life. The Düsseldorf School became internationally renowned for its narrative paintings and landscapes.

Munich also emerged as a major art center, rivaling Berlin and Düsseldorf. The Munich Academy attracted students from across Europe. Wilhelm Leibl, influenced by Courbet, became a leading proponent of Realism in Germany, focusing on peasant life with unsentimental honesty. His circle included artists like Wilhelm Trübner and Carl Schuch.

Towards the end of Engelhardt's reported activity (he purportedly died in 1883), new currents were emerging. The influence of French Impressionism began to be felt, leading to the development of German Impressionism with figures like Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. These artists, while adapting Impressionist techniques, often retained a distinct German character in their work. The Secession movements in Munich, Berlin, and Vienna (though Vienna is Austrian, its influence was felt in Germany) marked a break from academic conservatism, paving the way for modern art.

If Engelhardt studied in France and was influenced by Impressionism, he would have been part of a generation grappling with these new ideas. However, his described style – "fine details and balanced composition" – suggests he might have been more aligned with the academic traditions or the more meticulous forms of German Realism.

Connections and Contemporaries: A Web of Artistic Dialogue

An artist's development is rarely isolated. It occurs within a web of influences, rivalries, friendships, and broader artistic currents. While specific direct collaborations or master-student relationships for Georg Engelhardt are not clearly documented in easily accessible sources, we can consider the artistic figures whose work and ideas would have formed the backdrop to his career.

If he studied in Germany and France, he would have been aware of the leading academic figures of his youth. In Germany, this might include history painters like Peter von Cornelius or landscapists from the Düsseldorf School. In France, the salons would have showcased works by established masters like Ingres or later, the Realists like Courbet.

The mention of his being influenced by French Impressionism, if accurate, places him in dialogue with a revolutionary movement. He would have been contemporary with its key figures: Monet, Renoir, Degas, Pissarro, and Berthe Morisot. Their exhibitions, starting in the 1870s, caused considerable controversy and gradually shifted the course of Western art.

Within Germany itself, artists like Adolph Menzel (1815-1905) would have been a dominant presence, known for his historical paintings and early adoption of plein-air techniques. Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), a key figure of German Realism, would have been a younger contemporary. The portraitist Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904) achieved enormous success painting the prominent figures of his time.

The artistic environment of the late 19th century, which Engelhardt would have experienced in his later career, was incredibly rich and diverse. While his own work is described as more traditional, he would have been aware of the emerging Symbolist movement, with artists like Arnold Böcklin (Swiss-German) and Max Klinger exploring themes of myth, dream, and the subconscious.

The art world was also becoming more international. Artists traveled, studied abroad, and saw works from other countries through exhibitions and publications. Figures who would later become central to modern art, such as the sculptor Auguste Rodin in France, or painters like James Abbott McNeill Whistler (American, active in London and Paris) and John Singer Sargent (American, cosmopolitan), were gaining prominence. The Vienna Secession, founded in 1897 by artists like Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann, though occurring after Engelhardt's reported death, was the culmination of trends that were already building in the preceding decades – a desire for artistic renewal and a break from historicism. Even if Engelhardt was not directly part of these avant-garde circles, their activities would have contributed to the artistic climate of his later years.

Challenges in Documentation and Legacy

The task of reconstructing the life and work of an artist like Georg Engelhardt highlights the challenges inherent in art historical research, especially for figures who may not have achieved widespread contemporary fame or whose works have not been consistently curated and documented. Several factors can contribute to an artist's relative obscurity:

1. Regional Focus: The artist may have been primarily active in a specific region, with their works held in local collections or churches that are not widely digitized or cataloged internationally.

2. Loss or Misattribution of Works: Over time, artworks can be lost, destroyed, or misattributed, especially if signatures are unclear or if records are incomplete.

3. Changing Tastes: Artistic styles fall in and out of favor. Artists who were respected in their own time might be overlooked by later generations with different aesthetic preferences.

4. Lack of Self-Promotion or Biographical Record: Some artists are less adept at or interested in promoting their careers or leaving behind detailed personal records, letters, or diaries that can aid future historians.

5. Confusion with Contemporaries: As noted, the name Georg Engelhardt is not unique, and there were other individuals with similar names active in different fields during the 19th century. This can lead to confusion in attributions and biographical details. For instance, the British miniaturist George Engleheart (1750/52–1829) was a highly prolific and successful artist, but from an earlier period and different nationality. Similarly, the Viennese painter Josef Engelhart (1864–1941) was a significant figure in the Vienna Secession, but his dates and artistic circle are distinct.

The description of Georg Engelhardt's work as "balanced and not obtrusive, but sometimes lacking artistic innovation" might also play a role. While such qualities indicate solid craftsmanship and reliability, art history often tends to prioritize and celebrate the innovators, the rule-breakers, and those who dramatically shifted artistic paradigms. Artists who worked competently within established traditions, fulfilling commissions and contributing to the cultural fabric of their communities, can sometimes receive less scholarly attention.

Despite these challenges, the pursuit of understanding such artists is valuable. It provides a more nuanced and complete picture of art history, moving beyond the handful of great masters to appreciate the broader ecosystem of artistic production that existed in any given period.

Later Years and Potential Artistic Evolution

If Georg Engelhardt lived and worked until 1883, his career would have spanned a period of significant artistic shifts. The late 1870s and early 1880s saw Impressionism becoming more established, even if still controversial. In Germany, the foundations for Naturalism and later, German Impressionism, were being laid. The academic system was still powerful, but it was increasingly being challenged.

It is conceivable that Engelhardt's style might have evolved in his later years. Perhaps the "fine details" became somewhat looser, or his palette brightened under the influence of newer trends, even if he did not fully embrace Impressionism. Alternatively, he might have doubled down on his established style, continuing to serve patrons who appreciated traditional craftsmanship and subject matter. His portraiture, for example, might have continued to find a ready market among the conservative bourgeoisie.

His work in church painting might have continued, as religious institutions often favored more traditional styles. The demand for historical and allegorical paintings might have waned somewhat with changing tastes, but there would still have been opportunities for such commissions, particularly for public and official purposes.

Without access to a clear chronology of his works, tracing such an evolution remains speculative. However, it is rare for an artist to remain entirely static over several decades of practice. The changing world around them, new artistic ideas, and personal development invariably leave their mark.

Conclusion: An Artist in His Time

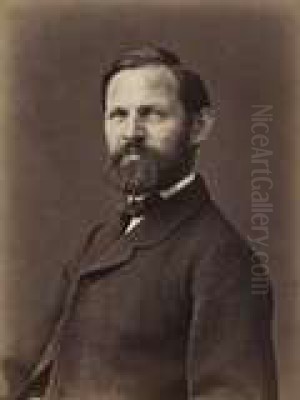

Georg Engelhardt (1823-1883), as depicted through the available fragments of information, emerges as a potentially skilled and versatile German painter of the 19th century. His work, encompassing church decoration, allegorical and historical scenes, and portraiture, suggests an artist well-versed in the academic traditions of his time. His style, characterized by meticulous detail and balanced composition, would have found appreciation among patrons who valued craftsmanship and established aesthetic norms.

While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or later avant-garde movements, his contributions, if they could be more fully documented and assessed, would likely reveal an artist who diligently plied his craft and contributed to the visual culture of his era. He operated within a rich and complex German art world, a contemporary to figures ranging from the late Romantics and Realists like Menzel to the emerging generation that would embrace Impressionism and Symbolism.

The story of Georg Engelhardt serves as a reminder of the vastness of art history and the many dedicated individuals whose work forms the intricate background to the more celebrated narratives. Further research into regional archives, church records, and private collections might one day bring his specific achievements into clearer focus, allowing for a more complete appreciation of this 19th-century German painter and his place within the artistic currents that shaped his world. His life and work, like that of many artists of his caliber, reflect the enduring human need to create, to represent, and to find meaning through the visual arts.