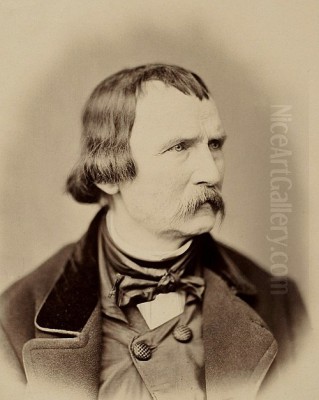

Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874) remains one of the most significant and, in his time, celebrated German painters of the 19th century. An artist of immense ambition and prolific output, he excelled as a painter of monumental historical frescoes, an insightful illustrator, and a powerful figure in the Munich art scene. His career spanned a pivotal period in German art, witnessing the zenith of Romanticism, the academic rigor of historical painting, and the nascent stirrings of new artistic directions. Kaulbach's work, characterized by grand narratives, dramatic compositions, and often a didactic or moralizing undertone, deeply resonated with the national and cultural aspirations of his era.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on October 15, 1805, in Arolsen, then part of the Principality of Waldeck, Wilhelm von Kaulbach's origins were modest. His father, Philipp Karl Friedrich Kaulbach, was a goldsmith and engraver who struggled financially, and his mother was Bavarian. This early exposure to craftsmanship, despite the family's poverty, likely provided an initial artistic impetus. The young Wilhelm received his first art lessons from his father, learning the fundamentals of drawing and engraving.

His formal artistic education began in 1822 when he enrolled at the prestigious Düsseldorf Academy of Art. This institution was rapidly becoming a leading center for art education in Germany, particularly known for its emphasis on historical painting and the Nazarene ideals of spiritual renewal in art. At Düsseldorf, Kaulbach became a pupil of the influential Peter von Cornelius (1783-1867), a leading figure of the Nazarene movement and a master of monumental fresco painting. Cornelius recognized Kaulbach's talent and took him under his wing, profoundly shaping his early artistic development and instilling in him a passion for grand-scale historical and allegorical subjects. Other artists associated with the Düsseldorf school at various times, though perhaps not direct peers in his student years, included figures like Carl Friedrich Lessing and Alfred Rethel, who also specialized in historical subjects.

The Munich Years and the Influence of Cornelius

In 1826, Kaulbach's career took a decisive turn when Cornelius, having been summoned to Munich by King Ludwig I of Bavaria to oversee vast decorative projects, invited his promising student to join him. Munich, under Ludwig I, was being transformed into a "new Athens on the Isar," a vibrant cultural capital adorned with neoclassical architecture and monumental art. Kaulbach thrived in this environment, continuing his studies under Cornelius and quickly becoming involved in major artistic undertakings.

He assisted Cornelius and collaborated with other students on significant commissions, such as the frescoes for the Glyptothek (a museum of Greek and Roman sculptures), the Odeon concert hall, and the arcades of the Hofgarten (Court Garden). These early projects provided invaluable experience in the techniques of fresco painting and the demands of large-scale public art. During this period, Kaulbach's style, while still heavily influenced by Cornelius's emphasis on clear outlines and didactic compositions, began to show signs of his own emerging individuality, particularly in his growing interest in dramatic narrative and psychological expression. He worked alongside other artists who were part of Cornelius's circle, such as Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1794-1872), another prominent Nazarene and historical painter also active in Munich.

Travels and Stylistic Maturation

To further broaden his artistic horizons and study the masterpieces of the past, Kaulbach undertook important study trips. In 1835, he traveled to Venice, where the rich colors and dramatic light effects of Venetian masters like Titian and Tintoretto made a lasting impression on him. This experience began to temper the somewhat austere linearity he had inherited from the Nazarene tradition, introducing a greater sensuousness and painterly quality to his work.

Between 1835 and 1839, Kaulbach made extended visits to Rome. The Eternal City, with its unparalleled artistic heritage from antiquity, the Renaissance, and the Baroque, was a pilgrimage site for artists from all over Europe. Here, he immersed himself in the study of Raphael's frescoes in the Vatican Stanze and Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel ceiling, works that exemplified the "grand manner" of historical painting. These Italian experiences were crucial in refining his compositional skills, his understanding of human anatomy, and his ability to orchestrate complex multi-figure scenes. The influence of Italian art, particularly its emphasis on color and light, became increasingly evident in his subsequent works, distinguishing him from the more strictly linear approach of some of his Nazarene-influenced contemporaries.

Master of Monumental Murals

Kaulbach's reputation as a leading historical painter was firmly established through his monumental mural cycles, which adorned public buildings and royal palaces. His ability to conceive and execute vast, complex compositions teeming with figures and imbued with historical or allegorical significance was unparalleled among his German contemporaries, save perhaps for his mentor Cornelius.

The Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus

Perhaps his most famous single mural, The Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus, was commissioned by King Ludwig I for the Neue Pinakothek in Munich. Executed between 1836 and 1846 (though some sources indicate slightly different timelines for various versions or cartoons), this colossal painting depicts the dramatic and tragic sack of Jerusalem by the Roman army in 70 AD. Kaulbach filled the canvas with a maelstrom of activity: fleeing Israelites, avenging Roman soldiers, the High Priest committing suicide, and the figure of Titus entering on horseback. The work was lauded for its dramatic power, its learned historical detail, and its complex allegorical allusions, which were interpreted as representing the triumph of Christianity over Judaism. A version or large-scale cartoon of this work also found its way to Berlin, highlighting its widespread acclaim.

The Battle of the Huns (Hunnenschlacht)

Another iconic work is The Battle of the Huns, created between 1834 and 1837 as a fresco for the staircase of the Neues Museum in Berlin (though the most famous version is the oil painting). This epic composition visualizes the legendary battle on the Catalaunian Plains in 451 AD between the Huns led by Attila and the Romans and Visigoths. Kaulbach depicted the battle not merely as a terrestrial conflict but as a supernatural event, with the spirits of slain warriors continuing the fight in the heavens above. This imaginative and dramatic interpretation captured the Romantic fascination with the medieval past and the sublime. The painting famously inspired the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt (1811-1886) to write his symphonic poem "Hunnenschlacht" in 1857, a testament to the painting's evocative power and cross-disciplinary influence.

Other Major Mural Cycles

Kaulbach was responsible for extensive fresco cycles in the Neues Museum in Berlin, commissioned by King Friedrich Wilhelm IV of Prussia. These cycles, executed over many years (roughly 1847-1866), aimed to depict the entire history of humanity in six major frescoes: The Tower of Babel, Homer and the Greeks (or The Age of Homer), The Destruction of Jerusalem, The Battle of the Huns, The Crusades (specifically, The Entry of the Crusaders into Jerusalem), and The Age of Reformation. These monumental works showcased Kaulbach's encyclopedic knowledge, his skill in organizing vast narratives, and his ambition to create a visual encyclopedia of world history from a 19th-century German perspective. Unfortunately, many of these Berlin frescoes were severely damaged or destroyed during World War II.

His work for the Neue Pinakothek in Munich also included other significant frescoes beyond The Destruction of Jerusalem, contributing to the museum's role as a showcase of contemporary German art. These large-scale projects solidified his position as a successor to Cornelius in the realm of monumental painting.

A Prolific Illustrator and Satirist

Beyond his monumental frescoes, Wilhelm von Kaulbach was a highly accomplished and popular illustrator. He produced illustrations for a wide range of literary works, demonstrating his versatility and his keen understanding of narrative.

He created memorable illustrations for the works of German literary giants like Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (e.g., Hermann und Dorothea) and Friedrich Schiller. His ability to capture the spirit and key moments of these texts made his illustrated editions highly sought after. He also illustrated Shakespeare, further showcasing his broad literary interests.

Reineke Fuchs (Reynard the Fox)

Kaulbach achieved particular fame for his satirical illustrations, most notably for Goethe's version of the medieval beast epic Reineke Fuchs (Reynard the Fox), published in 1846. His witty and sharply observed drawings, which anthropomorphized animals to satirize human follies and societal vices, were immensely popular. These illustrations revealed a different side of Kaulbach: a keen observer of human nature with a biting sense of humor, contrasting with the high seriousness of his historical frescoes. The success of Reineke Fuchs placed him in the company of other great European illustrators of the era, such as the French artist Gustave Doré (1832-1883), though their styles differed.

Das Narrenhaus (The Madhouse)

An earlier series of drawings, Das Narrenhaus (circa 1828-1834), also demonstrated his penchant for social commentary and psychological exploration. These powerful and somewhat unsettling images depicted the inmates of a lunatic asylum, exploring themes of madness, societal alienation, and the fragility of the human mind. These works, with their stark realism and empathetic yet unflinching gaze, were quite radical for their time and showed an early interest in subjects that lay outside the conventional academic repertoire. They prefigure later artistic explorations of psychological states and social outcasts.

His illustrations for children's books also enjoyed popularity, showcasing a lighter, more charming aspect of his talent.

Artistic Style, Techniques, and Influences

Wilhelm von Kaulbach's artistic style was a complex amalgamation of various influences, primarily rooted in German Romanticism and academic Classicism. He was a history painter par excellence, believing in art's didactic and moralizing function.

His early training under Cornelius imbued him with the Nazarene emphasis on clear outlines, strong drawing, and compositions that conveyed intellectual or spiritual ideas. However, his Italian travels, particularly his exposure to Venetian color and Roman High Renaissance grandeur, led to a richer, more painterly approach and a greater dynamism in his compositions.

Kaulbach was a master of orchestrating large, multi-figure scenes, often filled with dramatic action and expressive gestures. His historical paintings were meticulously researched, reflecting the 19th-century historicist interest in accuracy of costume and setting, though always subservient to the overall dramatic and allegorical intent. He shared this dedication to historical detail with contemporaries like the Belgian painter Hendrik Leys (1815-1869) or the French historical painters Paul Delaroche (1797-1856) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), though Kaulbach's allegorical tendencies were often more pronounced.

A significant technical aspect of his mural work was his adoption and promotion of stereochromy, also known as "water-glass painting." This technique, developed by Johann Nepomuk von Fuchs and Josef Schlotthauer in Munich, involved using a silica-based binder (water glass) to fix pigments to the wall, resulting in highly durable and luminous frescoes. Kaulbach, along with Cornelius, championed this method, which was seen as an improvement over traditional buon fresco for the German climate.

His style, while grand and often theatrical, could sometimes be perceived as overly academic or declamatory, particularly by later generations with different aesthetic sensibilities. However, within the context of 19th-century official art and the desire for national cultural expression, his work was immensely influential. He was a contemporary of other prominent German-speaking artists like the Romantic painter Moritz von Schwind (1804-1871), known for his fairy-tale subjects, and the Biedermeier master Carl Spitzweg (1808-1885), whose intimate and humorous genre scenes offered a contrast to Kaulbach's monumentalism.

The Director of the Munich Academy

In 1849 (some sources state 1843, but 1849 is more commonly cited for the directorship itself after a period of professorship), Kaulbach achieved a pinnacle of academic recognition when he was appointed Director of the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, succeeding his former mentor, Peter von Cornelius. He held this prestigious position until his death in 1874.

As Director, Kaulbach wielded considerable influence over art education in Munich and, by extension, in Germany. He trained a generation of artists, although the Munich Academy under his tenure, and that of his contemporary Karl von Piloty (1826-1886) who taught history painting, was often seen as upholding a conservative, academic tradition. Piloty, known for his more realistic and coloristically rich historical paintings like Seni an der Leiche Wallensteins, represented a slightly different, though still academic, approach to history painting compared to Kaulbach's more idealized and allegorical style. Students who passed through the Munich Academy during this period included artists who would later break away from academicism, such as Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), a key figure in German Realism, and Franz von Lenbach (1836-1904), who became a celebrated portrait painter.

Later Works and Shifting Perceptions

In his later career, Kaulbach continued to produce large-scale works, including paintings like The Deluge and The Sea Battle of Salamis (1868), the latter for the Maximilianeum in Munich. While these works maintained his characteristic grandeur and ambition, some critics felt his style became increasingly theatrical and, at times, prone to exaggeration or a certain coldness, lacking the freshness of his earlier achievements.

His personal life saw a shift in religious conviction; originally Protestant, he developed a strong sympathy for Catholicism, which reportedly led to a cooling of his relationship with the staunchly Protestant Cornelius. This internal spiritual journey, however, did not overtly manifest in a radical change in his public artistic themes, which remained broadly historical and allegorical.

By the time of his death, artistic tastes were beginning to shift. The rise of Realism, and soon Impressionism, challenged the dominance of academic historical painting. Artists like Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) in France had already championed a more direct engagement with contemporary life, and in Germany, figures like Adolph Menzel (1815-1905) were also moving towards a more realistic and less idealized depiction of history and everyday scenes.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Kaulbach's most significant collaborative relationship was undoubtedly with Peter von Cornelius, his teacher and early mentor. They worked together on numerous projects in Munich, and Cornelius's influence on Kaulbach's commitment to monumental, idea-driven art was profound.

His connection with Franz Liszt through The Battle of the Huns is a notable example of inter-artistic inspiration. While not a direct collaboration in the sense of working together on a single piece, the mutual respect and influence were clear.

In Munich, Kaulbach was a central figure in a vibrant artistic community. Besides those already mentioned (Cornelius, Schnorr von Carolsfeld, Piloty, Schwind, Spitzweg, Lenbach, Leibl), other important artists active in or associated with Munich during parts of his career included the classicist history painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829-1880) and the Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin (1827-1901), both of whom spent time in the city. The artistic environment was rich and varied, even if the Academy under Kaulbach represented a more traditionalist stance. The mention of "Der Blaue Reiter" in the initial prompt seems anachronistic for direct collaboration, as this Expressionist group was founded much later, in 1911, by artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, though they too were based in Munich and reacted against the academic traditions that Kaulbach had represented.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Wilhelm von Kaulbach died in Munich on April 7, 1874, during a cholera epidemic. At the time of his death, he was one of Germany's most famous and honored artists, a Knight of the Prussian Order Pour le Mérite for Arts and Sciences, and a member of numerous European academies. His son, Hermann von Kaulbach (1846-1909), also became a painter, specializing in genre scenes and portraits, continuing the family's artistic lineage.

Kaulbach's influence on subsequent generations of painters was significant, particularly in the realm of historical and monumental painting in Germany. His students and followers continued his tradition, though the grand, allegorical style he championed gradually fell out of favor as modern art movements gained ascendancy.

His innovations in mural technique, particularly his use of stereochromy, had a lasting impact on the practice of wall painting. His illustrations, especially the satirical Reineke Fuchs, maintained their popularity long after his death and are still appreciated for their wit and draftsmanship.

While his monumental historical paintings might seem less aligned with contemporary aesthetic sensibilities, they remain crucial documents of 19th-century German culture, reflecting its historical consciousness, national aspirations, and the prevailing artistic ideals of the era. His exploration of profound themes such as war, faith, madness, and the sweep of human history, even if presented in a highly theatrical manner, speaks to the ambitious intellectual scope of his art. Artists like Hans Makart (1840-1884) in Vienna, with his own opulent historical and allegorical canvases, shared a similar ambition for grand-scale "Makartstil" painting, reflecting a broader Central European trend.

The destruction of many of his Berlin frescoes in World War II was a tragic loss, depriving future generations of the full impact of some of his most ambitious undertakings. However, surviving works, cartoons, and reproductions continue to attest to his formidable talent and his central role in 19th-century German art.

Conclusion

Wilhelm von Kaulbach was a product of his time and a shaper of its artistic landscape. A master of the grand historical narrative, a witty illustrator, and an influential academic figure, he embodied the ambitions and contradictions of 19th-century German art. His dedication to art as a vehicle for moral and historical instruction, combined with his technical skill and imaginative power, secured him a prominent place in the pantheon of German artists. While tastes may have evolved, his work remains a vital key to understanding the cultural and artistic currents of his era, a testament to a vision that sought to capture the entirety of human experience on a monumental scale. His legacy, though perhaps less universally lauded today than in his lifetime, endures in the history of art as that of a true colossus of his age.