Introduction: A Master of Quiet Observation

Georg Flegel (1566–1638) stands as a seminal figure in the history of German art, celebrated primarily as one of the earliest and most significant proponents of still life painting north of the Alps. Born in Olmütz, Moravia (now Olomouc, Czech Republic), Flegel spent the most productive years of his career in Frankfurt am Main. In an era when historical and religious subjects dominated the artistic hierarchy, Flegel dedicated his meticulous craft to the depiction of inanimate objects – arrangements of fruit, flowers, tableware, food, and small creatures. His work is characterized by its remarkable precision, subtle compositions, and often profound underlying symbolism, elevating the humble still life to a genre of independent artistic merit and quiet contemplation. He is widely regarded as the first German painter to specialize exclusively in still life, paving the way for future generations.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Georg Flegel's journey into the world of art began not in Germany, but likely in Vienna. While details of his earliest training remain scarce, it is firmly established that by the 1580s, he was working as an assistant in the workshop of the Flemish painter Lucas van Valckenborch the Elder (c. 1535–1597). Valckenborch, a respected artist known for his landscapes, market scenes, and allegorical works, operated a busy studio, first possibly in Antwerp, then Linz, and later Frankfurt. Flegel's role in Valckenborch's workshop was specialized; he was entrusted with painting the detailed still life elements – fruits, vegetables, game, and flowers – that often featured prominently within his master's larger compositions, particularly market and kitchen scenes.

This apprenticeship was crucial for Flegel's development. Working alongside Valckenborch exposed him to the Flemish tradition of detailed realism and compositional structure. Lucas van Valckenborch, along with his brother Marten van Valckenborch, belonged to a large family of painters who had fled the religious turmoil in the Southern Netherlands. Their presence in the German-speaking lands contributed significantly to the cross-pollination of artistic ideas between the Low Countries and Germany. Flegel's task of inserting intricate still life passages into larger narrative scenes honed his skills in observation and precise rendering, preparing him for his eventual focus on still life as an independent subject.

The Move to Frankfurt and Artistic Independence

Around 1592 or 1593, Lucas van Valckenborch relocated his workshop to Frankfurt am Main, a thriving commercial and cultural hub in the Holy Roman Empire. Georg Flegel followed his master to this bustling city, which would become his home and the center of his artistic activity for the rest of his life. Frankfurt's status as a major trade fair city meant it attracted merchants, patrons, and artists from across Europe, creating a vibrant environment conducive to artistic innovation and exchange. The city already hosted a significant community of artists, including immigrants from the Netherlands.

In Frankfurt, Flegel continued to collaborate with Valckenborch for a time. However, he soon began to establish himself as an independent master. A key milestone was achieved on April 28, 1597, when Georg Flegel was granted citizenship (Bürgerrecht) in Frankfurt. This status allowed him to operate his own workshop, take on apprentices, and fully participate in the city's artistic life. It marks the beginning of his mature period, during which he increasingly focused on pure still life painting, moving beyond the role of an assistant to develop his distinctive personal style. His decision to specialize in still life was relatively novel in Germany at the time, distinguishing him from contemporaries who might paint still life elements but rarely as the sole subject.

Frankfurt: A Crucible for Still Life

The city of Frankfurt provided fertile ground for the development of still life painting. Its wealthy merchant class, influenced by both German traditions and the tastes of the nearby Netherlands, constituted a growing market for smaller-scale paintings suitable for domestic interiors. Unlike grand historical or religious commissions often favored by the church or aristocracy, still life paintings appealed to bourgeois patrons who appreciated meticulous craftsmanship, the depiction of familiar objects, and often, the subtle moral or symbolic messages embedded within these works.

Flegel was not entirely alone in his pursuit in the region. While he is considered the leading German pioneer, the environment included other artists exploring related themes. The influence of Flemish and Dutch painters was palpable. Artists like Gillis van Coninxloo III (1544-1607), a prominent landscape painter, also settled in Frankfurt for a period, contributing to the Netherlandish artistic presence. Peter Binoit (c. 1590-1632), another painter active in Frankfurt and nearby Hanau, also specialized in still lifes, particularly flower pieces, around the same time as Flegel, though Flegel's career began earlier. Isaak Soreau (1604-1644), born in Hanau to Flemish parents, became known for his meticulous fruit still lifes, clearly showing the influence of the Frankfurt school initiated by Flegel. Sebastian Stoskopff (1597-1657), from Strasbourg but likely influenced by the Frankfurt developments, would become another major figure in German still life slightly later. Flegel's work, therefore, emerged within a dynamic context of artistic exchange and a burgeoning market for this new genre.

Artistic Style: Precision, Composition, and Light

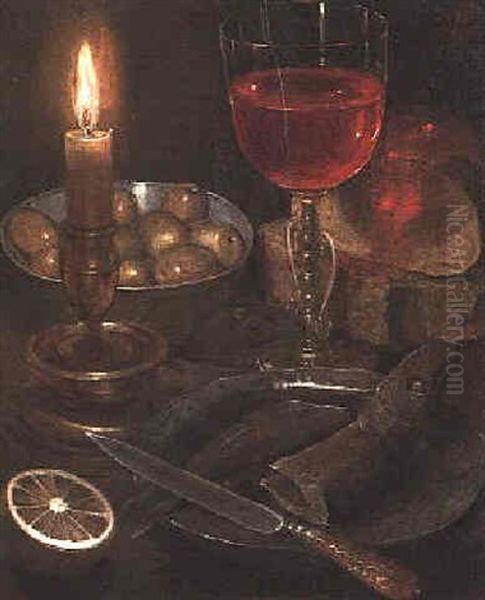

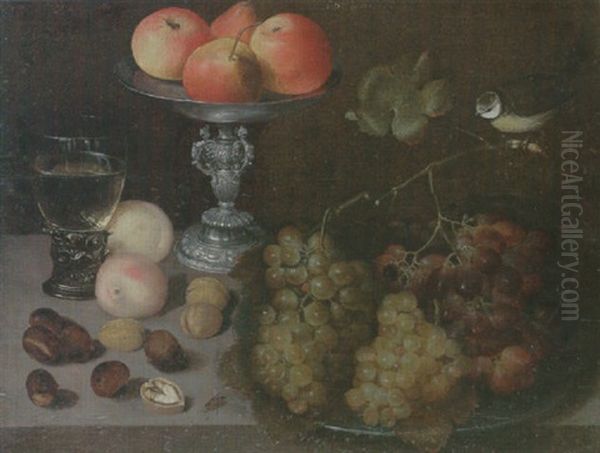

Georg Flegel's style is defined by its clarity, precision, and intimate focus. He typically worked on a relatively small scale, often using oil on panel or copper, mediums that allowed for fine detail. His compositions are usually straightforward, often featuring objects arranged on a simple wooden tabletop, viewed from a slightly elevated perspective. This clarity of arrangement allows the viewer to appreciate each object individually while also grasping the harmony of the whole.

His rendering of textures is exceptionally skillful. Flegel masterfully depicted the smooth, reflective surfaces of glass Roemer wine glasses, the dull gleam of pewter plates, the rough skin of bread, the delicate translucency of grapes, the fuzzy peel of peaches, and the intricate patterns on nuts or confectionery. He paid close attention to the play of light and shadow, using it to model forms and create a sense of volume and space. While often employing a clear, even light, some works incorporate the dramatic effect of candlelight, casting long shadows and imbuing the scene with a sense of intimacy and the passage of time.

Beyond oil painting, Flegel was also a highly accomplished watercolorist. Numerous detailed studies of individual flowers, plants, and insects survive, executed with botanical and entomological accuracy. These watercolors, sometimes used as preparatory studies but often existing as independent works of art, showcase his keen powers of observation and delicate handling of the medium. They rival the nature studies produced by contemporaries like Joris Hoefnagel (1542-1601), known for his manuscript illuminations and natural history illustrations.

Subject Matter: The Everyday Transfigured

Flegel's chosen subjects were drawn from the everyday world around him, particularly items related to meals and domestic life. His paintings frequently feature arrangements of:

Food and Drink: Bread, cheese, nuts, pretzels, confectionery, wine in glasses, beer in stoneware jugs.

Fruits: Grapes, peaches, apples, plums, cherries, strawberries, often depicted with remarkable freshness, sometimes showing signs of incipient decay.

Flowers: Bouquets in simple vases or glasses, featuring common garden flowers like tulips, roses, irises, columbines, and carnations.

Tableware: Pewter plates, knives with ornate handles, ceramic bowls, stoneware jugs, delicate Venetian-style glassware.

Small Creatures: Insects like flies, beetles (famously, the stag beetle), butterflies, and occasionally small animals like mice or birds.

These objects were not merely recorded with dispassionate accuracy; Flegel imbued them with a sense of presence. The arrangements often feel carefully considered, yet naturalistic. The inclusion of insects or slight imperfections (a bruised fruit, a wilting petal) adds a layer of realism and often contributes to the symbolic meaning of the work.

Symbolism and the Vanitas Theme

While Flegel's paintings delight in the realistic depiction of objects, they are rarely just exercises in technical skill. Like many Northern European still lifes of the period, his works are often laden with symbolic meaning, reflecting religious beliefs, moral precepts, and philosophical reflections on life and mortality. This aligns with the Vanitas tradition, which emphasized the transience of earthly pleasures and the inevitability of death.

Common symbolic interpretations in Flegel's work include:

Bread and Wine: Directly referencing the Eucharist, symbolizing Christ's sacrifice and the promise of salvation. Their frequent inclusion elevates a simple meal scene to a moment of quiet religious contemplation.

Fish: Often associated with Christ (the ichthys symbol) and also with fasting or Lent.

Fruits and Flowers: Can symbolize the bounty of nature and God's creation, but also their ephemeral nature. Blooming flowers and ripe fruit represent life and beauty, while wilting petals, decaying fruit, or the presence of insects serve as reminders of decay and the fleetingness of life (Vanitas). Specific flowers, like roses (love, martyrdom) or irises (sorrow of the Virgin), carried particular connotations.

Insects: Flies were often symbols of decay, sin, or the devil. Butterflies could symbolize the resurrected soul. Beetles, like the stag beetle, might carry complex associations, sometimes linked to Christ due to misconceptions about their life cycle, or simply representing the wonders and details of God's creation.

Snuffed Candles or Oil Lamps: Direct symbols of the passage of time and the brevity of human life.

Glassware: The fragility of glass could symbolize the fragility of life. Wine within the glass often carried Eucharistic significance.

Nuts: Sometimes symbolized the hidden divinity of Christ (kernel within the shell).

Flegel's symbolism is generally subtle, integrated naturally into the composition rather than being overtly didactic. The overall mood is often one of quiet reflection, inviting the viewer to contemplate the beauty of the material world while remaining mindful of its impermanence and spiritual significance. This blend of realism and symbolism was characteristic of still life painting in both the Netherlands, by artists like Osias Beert the Elder (c. 1580-1624) and Clara Peeters (fl. 1607-1621), and in Flegel's German context.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several key works exemplify Georg Flegel's style and thematic concerns:

_Still Life with Bread and Confectionery_ (c. 1630, Städel Museum, Frankfurt): This painting showcases Flegel's mastery in rendering different textures. A simple meal of bread, wine in a Roemer glass, and nuts is laid out on a table. Notably, it includes candied fruit or other sweets, displaying the crystalline structure of sugar with incredible precision. The work highlights the introduction of sugar, still a relative luxury, into the European diet. The composition is balanced, the lighting clear, emphasizing the materiality of the objects.

_Still Life with Stag Beetle_ (1635, Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne): One of Flegel's most famous works, this painting features a diagonal composition leading the eye from a bread roll and knife in the foreground, past fruits (peaches, grapes) and nuts, towards a tall glass of wine. A prominent stag beetle rests near the fruit. The inclusion of the beetle adds a point of interest and potential symbolic weight – perhaps representing nature's resilience, or even carrying Christological undertones debated by scholars. The meticulous detail, especially in the beetle and the reflections on the glass, is characteristic of Flegel's late style.

_Breakfast Still Life with Lidded Goblet_ (also known as _Dessert Still Life_) (c. 1630-1638, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna): This work presents a more elaborate arrangement, perhaps a dessert course. It features a tall, ornate lidded goblet (Deckelpokal), various fruits, nuts, and a bread roll, arranged on a white tablecloth. The complexity of the reflections on the goblet and the varied textures demonstrate Flegel's technical prowess. The richness of the items might hint at worldly wealth, while their inherent perishability subtly invokes the Vanitas theme.

_Flower Pieces_: Flegel created numerous paintings and watercolors focusing solely on flowers. Works like _Bouquet of Flowers in a Vase_ (various versions exist, e.g., in the Historisches Museum, Frankfurt) depict carefully arranged assortments of different species, often including insects. These works celebrate the beauty of nature but also, through the mix of flowers at different stages of bloom and the presence of insects, remind the viewer of the cycle of life and death. They stand alongside the work of dedicated flower painters like Ambrosius Bosschaert the Elder (1573-1621) and Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) in the Low Countries.

_Collaboration with Valckenborch_: Works like _Vegetable Market_ (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna), primarily painted by Lucas van Valckenborch, clearly show Flegel's contribution in the detailed rendering of the abundant vegetables and fruits displayed in the market stalls. These early collaborative works provide insight into Flegel's formative years and his initial specialization.

Relationships with Contemporary Artists

Flegel's career unfolded within a network of artistic relationships, primarily centered around Frankfurt.

Lucas van Valckenborch: His most significant relationship was with his master. Flegel's early style was shaped by Valckenborch's workshop practices, and their collaboration lasted for several years even after the move to Frankfurt. Valckenborch provided Flegel with foundational training and professional integration into the Frankfurt art scene.

Jacob Marrel (1613/14–1681): Flegel's most important pupil was Jacob Marrel, who entered his workshop around 1627. Marrel absorbed Flegel's meticulous style and focus on still life, particularly flower painting. Marrel later moved to Utrecht, where he studied with the flower painter Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606–1684), further developing his style. Marrel himself became a significant still-life painter and, importantly, was the teacher of Abraham Mignon (1640–1679), another famous flower painter, thus transmitting Flegel's influence to subsequent generations. Marrel also maintained connections with Frankfurt throughout his life.

Frankfurt Milieu: Flegel interacted with the broader community of artists in Frankfurt. While direct collaborative evidence beyond Valckenborch is limited, he would certainly have been aware of, and likely known personally, other painters active in the city, including fellow still-life specialists like Peter Binoit. The presence of numerous Flemish and Dutch artists created an environment of stylistic exchange.

Wider Context: Flegel's work should be seen in the context of early Baroque still life painting across Northern Europe. His precision and symbolic depth resonate with the work of Flemish pioneers like Osias Beert the Elder and Clara Peeters, and Dutch masters such as Floris van Dijck (c. 1575-1651) and Nicolaes Gillis (fl. 1601-c. 1632), who specialized in 'ontbijtjes' (breakfast pieces) and 'banketjes' (banquet pieces). While direct influence is hard to trace definitively without more documentation, the shared cultural and artistic currents are evident. Balthasar van der Ast (1593/94–1657), known for his detailed shell and flower paintings, was a contemporary whose work shows parallel developments in meticulous realism.

Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688): The artist and influential art historian Joachim von Sandrart mentioned Flegel in his seminal work, the "Teutsche Academie" (German Academy) of 1675. Sandrart praised Flegel's skill, particularly in depicting flowers and confectionery, helping to preserve his name and reputation for posterity, even if briefly mentioned.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Georg Flegel's primary importance lies in his pioneering role in establishing still life as an independent and respected genre within German art. At a time when German painting was arguably less innovative than that of Italy or the Netherlands, Flegel carved out a niche of exceptional quality and influence.

His contributions include:

Establishing German Still Life: He was arguably the first German artist to dedicate his career almost exclusively to still life, demonstrating its potential for artistic expression and intellectual depth.

Technical Mastery: His meticulous technique, particularly in rendering textures and details, set a high standard for realism in the genre. His watercolors are among the finest natural history studies of the period.

Subtle Symbolism: He skillfully integrated symbolic meaning into his depictions of everyday objects, enriching the genre beyond mere representation and connecting it to broader cultural and religious concerns (Vanitas, Eucharist).

Influence: Through his own work and his pupil Jacob Marrel, Flegel's influence extended to later still-life painters in Germany and potentially the Netherlands. He helped shape the character of the Frankfurt school of still life painting.

Despite his significance, Flegel fell into relative obscurity for centuries after his death. The Thirty Years' War (1618-1648), which ravaged German lands during the latter part of his life and after, disrupted artistic production and patronage. Furthermore, shifts in taste in later periods perhaps favored grander or more dramatic styles. It was only in the late 19th and 20th centuries that art historians rediscovered Flegel's work and recognized his crucial role in the development of still life painting.

Challenges in Studying Flegel

Research on Georg Flegel faces certain challenges. Biographical information remains limited, pieced together primarily from archival records like his citizenship grant and mentions by contemporaries like Sandrart. Many details about his training, travels (if any beyond Vienna and Frankfurt), patrons, and workshop practices are unknown.

Furthermore, the surviving body of his work, while significant, is not vast. Around 110 oil paintings are generally attributed to him, along with numerous watercolors. Many works may have been lost over the centuries due to wars, neglect, or misattribution. Dating his works precisely is often difficult, as he rarely signed and dated them, requiring stylistic analysis to establish a chronology. These factors make a complete understanding of his artistic development and output challenging, though ongoing research continues to shed light on his life and work.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Quiet Beauty

Georg Flegel remains a pivotal figure in the history of European still life. As Germany's first major specialist in the genre, he brought a unique sensibility to the depiction of the inanimate world. His paintings are characterized by an extraordinary combination of meticulous realism, compositional clarity, and subtle symbolic resonance. He found profound beauty and meaning in the everyday objects of the pantry and the table, rendering them with a dedication that elevates them beyond the mundane.

Working in the bustling artistic center of Frankfurt, Flegel absorbed influences from the Netherlandish tradition through his master Lucas van Valckenborch, yet forged a distinctively German interpretation of the still life genre. His legacy endured through his pupil Jacob Marrel and his influence on the Frankfurt school, contributing significantly to the rich tapestry of Northern European Baroque art. Though once overlooked, Georg Flegel is now rightly celebrated as a master of quiet observation, whose works continue to captivate viewers with their intricate detail, serene beauty, and contemplative depth. His art reminds us of the value of close looking and the potential for finding significance in the seemingly ordinary aspects of life.