Introduction: Clarifying an Identity

In the annals of Italian art history, the name Michelangelo resonates with unparalleled grandeur, primarily associated with the Renaissance titan Michelangelo Buonarroti. However, the rich tapestry of Italian art features another significant figure bearing this name, albeit one who carved his niche in a different era and genre: Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio. It is crucial from the outset to distinguish this Michelangelo, a prominent painter of the Baroque period specializing in still life, from his vastly more famous namesake.

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio, often simply referred to as "il Campidoglio," was an Italian artist active primarily in Rome. While Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) dominated the High Renaissance with his monumental sculptures, frescoes, and architectural designs, Michelangelo Pace (believed to have been born around 1610 or 1620 and died around 1670) flourished during the subsequent Baroque era. His domain was not the human form in dramatic narrative or divine representation, but the intricate beauty and symbolic potential of inanimate objects – fruits, flowers, and the accoutrements of daily life.

This artist belongs firmly to the Baroque period, a time of dramatic intensity, rich color, and profound emotional depth in art, following the intellectual complexities of Mannerism and the High Renaissance. His work is particularly associated with the development of still life painting in Rome, a genre that gained significant traction during the 17th century. He became renowned for his highly refined and detailed depictions, contributing significantly to the Roman school of still life.

Understanding Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio requires setting aside the shadow of Buonarroti and appreciating his contributions within his specific context: the vibrant, competitive, and artistically fertile environment of 17th-century Rome, where the still life genre was blossoming into a respected and sought-after form of artistic expression. His legacy lies in the exquisite quality of his canvases and his role in shaping the trajectory of Baroque still life painting in Italy.

The Flourishing Genre: Still Life in Baroque Rome

The 17th century witnessed a remarkable rise in the popularity and status of still life painting across Europe, and Rome was a vibrant center for this development. Previously often considered a lesser genre compared to history painting or portraiture, still life found fertile ground in the cultural and economic climate of the Baroque era. Several factors contributed to its ascent in the Eternal City.

Patronage played a crucial role. Wealthy Roman families, cardinals, and visiting dignitaries developed a taste for paintings that celebrated nature's bounty, displayed technical virtuosity, or conveyed complex symbolic meanings. Collections like those of the Barberini, Chigi, and Pamphilj families often included exquisite examples of still life, demonstrating the genre's acceptance within elite circles. These patrons appreciated the decorative qualities of still lifes, using them to adorn their palaces and villas.

The influence of Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571-1610) cannot be overstated, even though he was primarily a figure painter. His revolutionary naturalism and dramatic use of chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) profoundly impacted Roman art. His famous `Basket of Fruit` (c. 1599) is often cited as a seminal work in Italian still life, showcasing an unprecedented level of realism and attention to the specific textures and imperfections of nature. This approach inspired subsequent generations of painters, including still life specialists.

Furthermore, Rome was a cosmopolitan hub attracting artists from across Italy and Europe, particularly from the Netherlands and Flanders, where still life traditions were already highly developed. Painters like Abraham Brueghel (1631-1697), Karel van Vogelaer (1653-1695), and Christian Berentz (1658-1722) brought their Northern sensibilities – meticulous detail, rich textures, complex compositions, and often intricate symbolism – to the Roman scene. This influx created a dynamic exchange of ideas and techniques, enriching the local school.

Within this context, Roman still life developed its own characteristics. While influenced by Northern precision, it often retained a certain Italianate grandeur, sometimes featuring more opulent arrangements or incorporating elements related to classical antiquity. The themes explored ranged from simple depictions of market produce to elaborate allegorical compositions, often touching upon vanitas subjects – reminders of the transience of life and the fleeting nature of earthly pleasures, symbolized by decaying fruit, wilting flowers, or skulls. Artists like Mario Nuzzi (1603-1673), known as 'Mario de' Fiori' for his specialization in flower painting, became highly successful, indicating the genre's commercial viability and artistic recognition.

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio: Life Amidst Roman Splendor

Biographical details about Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio remain relatively scarce compared to his more famous contemporaries, a common fate for artists specializing in genres outside the traditional academic hierarchy. Sources suggest a birth year around 1610 or, as indicated in some initial analyses, possibly 1620. His death is generally placed around 1670. His moniker, "del Campidoglio," likely refers to the Capitoline Hill (Campidoglio) in Rome, suggesting he may have lived or worked near this prominent landmark, or perhaps received patronage connected to institutions located there.

He was unequivocally an Italian artist, active throughout his career in Rome. The city during his lifetime was the undisputed center of the Catholic world and a major European artistic capital, undergoing significant urban transformation under papal patronage. This environment provided both opportunities and intense competition for artists. While the grand commissions for churches and palaces often went to figure painters and architects like Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) or Pietro da Cortona (1596-1669), there was a thriving market for other genres, including still life.

Details about Campidoglio's training are speculative. He may have apprenticed with an established still-life painter in Rome, perhaps absorbing techniques from both Italian traditions and the increasingly influential Northern artists active in the city. His style suggests a deep understanding of natural forms, meticulous observation, and a sophisticated handling of paint, indicating rigorous training.

His patrons likely included members of the Roman aristocracy and high clergy who appreciated the decorative elegance and technical skill evident in his work. The demand for high-quality still lifes to adorn private galleries and studioli was significant. Campidoglio's reputation for refinement and detail, noted even in early accounts, would have made his work desirable to discerning collectors seeking luxury goods that reflected their taste and status.

While specific documented interactions with other major artists are limited, he operated within a vibrant artistic milieu. He would have been aware of the works of leading painters like Andrea Sacchi (1599-1661) and the ongoing stylistic debates between the High Baroque exuberance of Cortona and the classicizing tendencies of Sacchi. More directly, he would have known the work of, and likely competed with, fellow still-life specialists like the aforementioned Mario Nuzzi and the various Northern painters who made Rome their temporary or permanent home. His career unfolded against the backdrop of Rome solidifying its position as the cradle of the Baroque style.

Artistic Style: Detail, Light, and Nature's Theater

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio earned renown for a style characterized by meticulous detail, refined execution, and a palpable sense of naturalism, all hallmarks highly valued in Baroque still life. His approach combined careful observation with a sophisticated artistic sensibility, transforming humble objects into subjects of compelling visual interest.

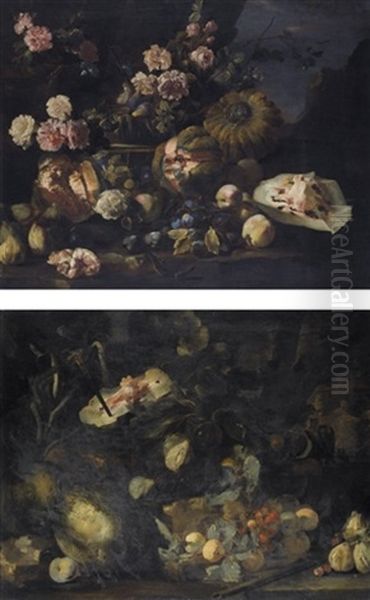

One of the most frequently noted aspects of his work is the high degree of finish and precision. He rendered the varied textures of fruits and flowers with remarkable skill – the velvety skin of a peach, the taut, reflective surface of grapes, the delicate translucency of petals, the rough rind of a melon. This attention to detail often extended to capturing ephemeral effects like dewdrops clinging to leaves or the subtle bloom on plums, enhancing the illusion of reality and showcasing his technical prowess. This pursuit of verisimilitude, sometimes bordering on trompe-l'oeil (fool the eye), was a popular feature of Baroque art, delighting patrons with its cleverness.

His compositions, while grounded in naturalism, often exhibit a Baroque dynamism. Rather than static, symmetrical arrangements, his still lifes frequently feature abundant, tumbling displays of fruit or flowers, creating diagonals and curves that lead the viewer's eye through the painting. Objects might spill over the edge of a table or ledge, seemingly entering the viewer's space, another characteristic Baroque device used to break down the barrier between the artwork and the observer.

The use of light is fundamental to his style. While perhaps not always employing the stark, dramatic chiaroscuro of Caravaggio's followers, Campidoglio skillfully used light and shadow to model forms, create depth, and highlight textures. Objects emerge from often dark, undefined backgrounds, spotlit to emphasize their color, shape, and tactile qualities. This controlled illumination adds a sense of theater and focuses attention on the beauty and richness of the natural world he depicted.

The concept of "Natura Morta" (still life, literally "dead nature") finds rich expression in his work. He celebrated the visual appeal of inanimate objects, finding beauty in the everyday bounty of nature. His subjects predominantly included fruits – grapes, figs, peaches, pomegranates, melons – and flowers, often arranged in baskets, on stone ledges, or combined with foliage. Some interpretations suggest that, in line with Baroque sensibilities, his works occasionally carried vanitas undertones. The depiction of overripe fruit or flowers past their prime could serve as subtle reminders of the passage of time, mortality, and the ephemeral nature of beauty and earthly possessions, a theme hinted at by the "Death and Fruits" or "Death and Nature" descriptions found in some analyses of his work.

Representative Works: Celebrating Abundance

While specific, universally recognized titles like Leonardo's `Mona Lisa` or his namesake's `David` do not dominate the discussion of Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio's oeuvre, his reputation rests firmly on a body of high-quality still life paintings, many of which are now housed in major museums and private collections. His representative works are best understood as variations on recurring themes, primarily centered on lavish displays of fruits and, to a lesser extent, flowers.

His fruit still lifes are perhaps his most characteristic creations. These paintings typically feature generous assortments of seasonal produce, often depicted with a sense of overflowing abundance. Grapes, with their complex clusters and translucent skins, were a favorite motif, rendered with exceptional skill. Peaches, plums, figs, pomegranates bursting open to reveal their jewel-like seeds, melons, and pears are also common subjects. These fruits are often arranged in baskets, on ornate platters, or directly onto stone ledges or draped cloths.

The compositions frequently create a sense of opulence and natural richness. Campidoglio masterfully captured the specific colors and textures of each fruit, making them appear almost tangible. The interplay of light across these varied surfaces – the soft fuzz of a peach contrasted with the smooth gleam of an apple – is a testament to his observational powers and technical facility. The dark backgrounds commonly employed serve to accentuate the vibrant colors and forms of the produce, pushing them forward towards the viewer.

Flower paintings, though perhaps less numerous or central to his identified output than fruit pieces, also form part of his known work, sometimes integrated with fruit arrangements. When depicted, flowers like roses, tulips (a popular subject in Baroque floral painting), carnations, and others are rendered with the same meticulous attention to detail seen in his fruit still lifes. The delicate structure of petals, the subtle gradations of color, and the freshness of the blooms are carefully conveyed.

While often celebratory in tone, showcasing the beauty and bounty of nature, the potential for underlying vanitas themes, as mentioned earlier, adds a layer of complexity. An insect resting on a piece of fruit, a slightly bruised apple, or a flower beginning to wilt could subtly invoke reflections on decay and the transient nature of life, enriching the viewing experience beyond mere visual delight. These works, therefore, stand as prime examples of Roman Baroque still life, balancing decorative appeal with technical virtuosity and potential symbolic depth.

Influences, Contemporaries, and Artistic Dialogue

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio did not create in a vacuum. His artistic development and style were shaped by the prevailing artistic currents of his time and his interactions, direct or indirect, with other artists. Understanding these connections helps to situate his work within the broader landscape of 17th-century European painting.

The shadow of Caravaggio looms large over most Roman Baroque art, and still life is no exception. Caravaggio's intense naturalism, his focus on depicting objects and people as they truly appeared, and his dramatic use of light provided a powerful model. While Campidoglio's lighting might be softer and his mood less overtly dramatic than Caravaggio's, the commitment to realism and the use of chiaroscuro to enhance form and texture clearly owe a debt to the earlier master. The very elevation of humble subjects like fruit to the status of high art can be traced back to Caravaggio's influence.

The mention of Titian (Tiziano Vecellio, c. 1488/1490-1576) as an influence, though from a much earlier period (High Renaissance Venice), might point towards an appreciation for rich color and painterly texture. Venetian painting, known for its emphasis on colorito (color and painterly application) over Florentine disegno (drawing and design), had a lasting impact on Italian art. Campidoglio's vibrant palette and tactile rendering of surfaces could reflect this broader Italian heritage, where sensuous visual appeal was highly valued.

More direct influences and parallels can be drawn with contemporary still-life painters active in Rome. Mario Nuzzi ('Mario de' Fiori') was a leading specialist, particularly known for his exuberant flower paintings, often collaborating with figure painters by adding floral garlands or backgrounds. Campidoglio's work, while perhaps more focused on fruit, shares the Baroque love for abundance and decorative richness seen in Nuzzi's canvases.

The presence of Northern artists in Rome was crucial. Flemish painters like Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625), though slightly earlier, had established a tradition of highly detailed and often encyclopedic flower and fruit paintings that influenced Italian artists. Later arrivals like Abraham Brueghel brought this Northern precision directly into Campidoglio's milieu. Comparing Campidoglio's work with that of Dutch masters of opulent still life, such as Willem Kalf (1619-1693), reveals shared interests in depicting luxury items and rich textures, although Campidoglio's style generally retains a distinctly Italian flavor, perhaps less focused on minute symbolic detail than some Northern counterparts.

Other Italian still-life painters offered different approaches. Fede Galizia (1578-1630), working mainly in Milan, was an early pioneer of the genre in Italy, known for her more austere and formally arranged compositions. Later, Evaristo Baschenis (1617-1677) in Bergamo specialized almost exclusively in still lifes of musical instruments, demonstrating the thematic diversification within the genre. Campidoglio's focus on fruit and flowers places him firmly within the mainstream of Roman still life production, where he distinguished himself through the quality and refinement of his execution. His work represents a successful synthesis of Italian traditions and Northern influences, tailored to the tastes of Roman patrons.

Legacy: A Refined Vision of Nature

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio occupies a significant, if specialized, place in the history of Italian Baroque art. While not a revolutionary figure on the scale of Caravaggio or Bernini, he excelled within his chosen genre, contributing substantially to the development and prestige of still life painting in 17th-century Rome. His legacy is primarily defined by the technical excellence and aesthetic appeal of his work.

His paintings were highly regarded in his own time for their refinement and detailed naturalism. He demonstrated that still life could be a vehicle for considerable artistic skill and sophisticated visual pleasure. By consistently producing works of high quality, he helped to solidify the genre's status among Roman patrons and collectors, moving it beyond mere decoration towards appreciated artistry. His success likely encouraged other artists to pursue still life specialization.

His style, characterized by meticulous rendering, rich color, often dynamic compositions, and skillful use of light, became influential within the Roman school of still life. Subsequent painters working in Rome likely looked to his works as models of technical achievement and compositional elegance. He set a standard for quality in the depiction of fruits and flowers that resonated with the Baroque taste for both naturalism and abundance.

While the vanitas elements in his work may be subtle compared to some Northern examples, his paintings participate in the broader Baroque exploration of themes related to nature, time, and sensory experience. They invite contemplation of the beauty of the created world, while perhaps gently hinting at its impermanence. This blend of visual delight and potential deeper meaning contributed to the genre's intellectual respectability.

Today, his works are sought after by museums and collectors specializing in Baroque art and still life painting. They are valued not only as beautiful objects but also as important documents of artistic taste and practice in 17th-century Rome. His paintings offer a window onto the period's fascination with the natural world, its appreciation for technical virtuosity, and the ways in which artists transformed everyday objects into compelling works of art.

Though often overshadowed by his towering namesake, Michelangelo Buonarroti, and by the leading figure painters of his own era, Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio carved out a distinct and admirable reputation. He remains a key figure for understanding the flourishing of still life painting in Baroque Italy, celebrated for his refined vision and masterful execution within this captivating genre. His canvases continue to delight viewers with their vibrant depiction of nature's bounty, captured with enduring skill and artistry.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of Campidoglio's Still Lifes

Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio stands as a testament to the depth and diversity of artistic talent flourishing in Baroque Rome. By dedicating his career to the genre of still life, he achieved a level of mastery and refinement that earned him recognition in his own time and ensures his relevance in art history today. Distinct from the monumental achievements of Michelangelo Buonarroti, Campidoglio's contribution lies in the intimate yet opulent world of "Natura Morta."

His paintings, predominantly lush arrangements of fruit rendered with meticulous detail and vibrant color, exemplify the high standards of Roman Baroque still life. He skillfully blended Italianate sensibilities for form and composition with the detailed naturalism spurred by Caravaggio and Northern European traditions. His work captured the Baroque era's fascination with the richness of the natural world, the appreciation of technical virtuosity, and the subtle interplay between sensory delight and deeper symbolic meaning, often touching upon themes of abundance and transience.

Navigating a competitive artistic environment that included masters like Mario Nuzzi and influential foreign painters like Abraham Brueghel, Campidoglio established a distinct reputation for quality and elegance. His legacy endures in the canvases that survive, admired for their technical brilliance, compositional harmony, and the sheer visual pleasure they offer. He remains a significant figure for anyone studying the evolution of still life painting in Italy, a master whose focused dedication produced works of lasting beauty and historical importance. Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio, the "Michelangelo of the Capitoline," thus holds his own unique and respected place in the grand narrative of Italian art.