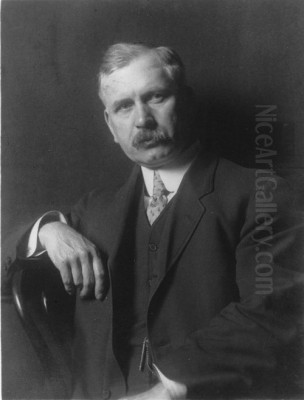

George Horne Russell stands as a notable figure in the Canadian art landscape of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A painter recognized for his landscapes and portraits, Russell navigated a period of significant artistic development in Canada, contributing through his work and his leadership within established art institutions. While perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries who would later forge a distinctly Canadian modernist path, Russell's career reflects the prevailing tastes and artistic currents of his era, particularly the enduring influence of European academic traditions.

Early Life and Transatlantic Journey

Born in the picturesque town of Banff, Scotland, in 1861, George Horne Russell's early life was steeped in the rich artistic and cultural heritage of his homeland. The dramatic landscapes of Scotland likely provided an initial, if subconscious, inspiration for his later artistic pursuits. The precise details of his early artistic training in Scotland are not extensively documented, but it is clear that he developed a proficiency that would serve him well upon his decision to emigrate.

In 1889, at the age of 28, Russell made the significant move across the Atlantic to Canada, choosing Montreal as his new home. Montreal, at this time, was a burgeoning metropolis and a key centre for commerce, culture, and artistic activity in Canada. This decision marked the beginning of his professional career in a new country, one that was itself in the process of forging its own national identity, with art playing an increasingly important role in that endeavour.

Establishing a Career in Montreal and the Notman Connection

Upon his arrival in Montreal, Russell quickly integrated into the city's artistic circles. One of his early and significant engagements was with the renowned photographic firm of William Notman & Son. In 1889, he was employed to colour photographs, a common practice at the time that bridged the gap between the monochrome reality of early photography and the public's desire for the vividness of painting. Working for Notman, a dominant figure in Canadian photography whose studio chronicled Canadian life and landscape extensively, would have provided Russell with invaluable exposure to Canadian subject matter and the visual tastes of the era.

The Notman studio was a hub of artistic activity, employing various artists for finishing, retouching, and colouring. This experience likely honed Russell's skills in observation and chromatic application, even if the medium was different from his primary pursuit of painting. It also placed him in contact with a commercial art world that was closely tied to the documentation and romanticization of Canada, themes that would recur in his later work, particularly his commissions.

The St. Andrews Retreat and Architectural Collaborations

While Montreal remained his primary base for many years, George Horne Russell developed a deep affection for St. Andrews, New Brunswick. This charming coastal town became his regular summer retreat, offering a different palette of landscapes and a tranquil environment conducive to artistic creation. He spent many summers there, capturing its scenic beauty in his works, particularly in a series of watercolors that showcased his skill in this medium.

His connection to St. Andrews was further solidified by his collaboration with the prominent Canadian architect William Sutherland Maxwell. Maxwell, along with his brother Edward Maxwell, formed one of Canada's most important architectural firms, responsible for many iconic buildings. Russell and William S. Maxwell enjoyed a close professional and personal relationship. This friendship led to Maxwell designing a summer residence for Russell in St. Andrews.

One notable architectural project linked to Russell is "Derry Bay," a custom-designed residence in St. Andrews. While the initial prompt mentions Russell designing custom works for Derry Bay, it is more accurately stated that the architectural firm Maxwell and Pitts (William Sutherland Maxwell being a principal) designed the house for George Horne Russell in 1924. This residence, and potentially another, stands as a testament to his presence in the community and his association with leading architectural figures of the day. Hope Horne Russell, presumably a relative, also resided with him in St. Andrews, sharing in this idyllic summer lifestyle.

Leadership at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts

George Horne Russell's standing within the Canadian art community grew steadily, culminating in a significant leadership role. In the early 1920s, he served as the President of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA) for a period of four years. The RCA, founded in 1880 under the patronage of the Marquis of Lorne, Canada's Governor General, and his wife, Princess Louise, was the preeminent art institution in Canada at the time. Its mission was to encourage and promote the visual arts in Canada through exhibitions, the establishment of a National Gallery, and the education of artists.

Serving as President of the RCA placed Russell at the forefront of the Canadian art establishment. This was a period of transition in Canadian art. While the RCA traditionally upheld academic standards rooted in European traditions, new artistic voices were beginning to emerge, challenging these conventions. Figures like Lucius O'Brien, the first president of the RCA, and later Robert Harris, known for his painting "The Fathers of Confederation," had established a strong foundation for the institution. Russell's presidency occurred just as artists like Tom Thomson (though deceased by then, his influence was growing) and the future members of the Group of Seven – including Lawren Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald, Arthur Lismer, Frederick Varley, Frank Johnston, Franklin Carmichael, and later A.Y. Jackson – were beginning to articulate a vision of Canadian landscape painting that was more rugged, nationalistic, and distinct from European models.

Russell's leadership would have involved navigating these evolving artistic currents, organizing RCA exhibitions, and representing Canadian art nationally. His tenure reflects a period where the academic tradition, which he largely represented, still held considerable sway, even as modernist influences began to take root. He was also an active member of the Canadian Handicrafts Guild, serving on its committee in 1910, indicating a broader interest in the applied arts and crafts movement which shared some philosophical ground with artists like William Morris in Britain.

Commissions and Notable Works: The C.P.R. and Beyond

Like many artists of his time, George Horne Russell undertook commissions, which provided financial support and public visibility. One of the most significant patrons of Canadian art during this period was the Canadian Pacific Railway (C.P.R.). The C.P.R. played a crucial role in opening up the Canadian West and actively commissioned artists to create works that would promote tourism and immigration by showcasing the grandeur of the Canadian landscape, particularly the Rocky Mountains.

Russell contributed to this body of C.P.R.-sponsored art. His painting "Kicking Horse Pass," dated 1900, is cited as his last known C.P.R. commission. This work would have depicted one of the iconic mountain passes traversed by the railway, a subject favored by many artists working for the C.P.R. However, some art historical accounts suggest that Russell's contributions to the C.P.R. project, while present, might not have reached the same level of acclaim or impact as those of some of his contemporaries who also worked for the railway, such as John Hammond or William Brymner. Brymner, an influential teacher and painter, also served as RCA president at a later date and produced significant works for the C.P.R. Similarly, F.M. Bell-Smith was another artist renowned for his depictions of the Rockies, often under C.P.R. patronage.

It's noted that the quality of C.P.R. commissions may have seen a shift after Thomas Shaughnessy became president of the company, with potentially more demanding requirements for artists. Russell's departure from direct C.P.R. commissions around 1900 might reflect these changing dynamics or his own shifting artistic focus.

Beyond specific C.P.R. works, Russell was known for his landscapes, including "Beaver Valley, Selkirk Mountains" and "The Hermit Range." These titles suggest a continued engagement with the majestic mountain scenery of Western Canada, a popular theme among Canadian artists aiming to capture the unique character of the nation's wilderness. His aforementioned watercolors of St. Andrews also form an important part of his oeuvre, showcasing a more intimate and perhaps personal engagement with the landscape of the Maritimes. His portraiture, though less specifically detailed in available records, was another facet of his artistic practice, common for academically trained artists of the period.

Artistic Style and Influences

George Horne Russell's artistic style was largely rooted in the academic traditions prevalent in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This typically involved a commitment to representational accuracy, skilled draughtsmanship, and a balanced compositional approach. His landscape paintings, whether of the grand Rockies or the coastal scenes of St. Andrews, would have aimed to capture the visual truth of the scene, often imbued with a romantic sensibility that emphasized the beauty and sometimes the sublime power of nature. His use of watercolors for some of his St. Andrews scenes aligns with a strong British tradition in that medium.

There is no strong evidence to suggest that Russell embraced the more avant-garde artistic movements that were developing in Europe and beginning to influence North America during his career, such as Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, or Cubism. He does not appear to have been directly associated with movements like Synchromism, an American modernist art movement founded by Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell (a different Russell) that focused on color abstraction.

Instead, George Horne Russell's work would have found kinship with other Canadian artists who adhered to a more traditional, albeit often highly skilled, approach to painting. Contemporaries like Homer Watson, known for his depictions of the Doon Pilon, Ontario, landscape, or Maurice Cullen and James Wilson Morrice, who, while more influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, still operated within a broadly representational framework before the full impact of the Group of Seven. Russell's art, therefore, can be seen as representative of a particular stream of Canadian art that valued established techniques and aesthetic ideals. The input mentioning "symbolism" and "sprites and fairies" or a focus on "inner light" seems to be a conflation with the Irish poet and painter George William Russell, known as "Æ," whose mystical and Theosophical themes are distinct from the known work of George Horne Russell, the Canadian artist.

Later Career and Legacy

Information about George Horne Russell's career after his presidency of the RCA in the early 1920s is less prominent. This period marked the ascendancy of the Group of Seven, who dramatically shifted the focus and style of Canadian landscape painting, championing a more nationalistic and modernist aesthetic. Artists adhering to older, more academic styles, while still respected, often found themselves outside the main thrust of critical and public attention which was increasingly captivated by this new vision of Canadian art.

Despite this shift, Russell's contributions remain part of the fabric of Canadian art history. His work for the C.P.R., his leadership of the RCA, and his consistent production of landscapes and portraits over several decades mark him as a dedicated professional artist. His paintings would have been exhibited regularly through the RCA and other venues, contributing to the cultural life of Canada.

The assessment that his contribution to Canadian art development was "relatively small" might reflect a comparison with more transformative figures. However, artists like Russell played an essential role in maintaining artistic institutions, fostering a general appreciation for art, and documenting the Canadian scene through a traditional lens. His connection with architect William S. Maxwell also highlights the interdisciplinary connections within the arts community of the time. Figures like Ozias Leduc, a Quebec painter known for his serene landscapes and church decorations, also worked in a more personal, less overtly nationalistic style, yet holds an important place.

Conclusion

George Horne Russell was an artist of his time, a Scottish immigrant who became a significant figure in the Canadian art establishment of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. From his early work colouring photographs for William Notman & Son to his presidency of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Russell demonstrated a consistent commitment to his craft. His landscapes, whether the grand vistas of the Canadian Rockies commissioned by the C.P.R. or the more intimate scenes of St. Andrews, reflect a traditional academic approach, skillfully executed.

While he may not have been an avant-garde innovator in the vein of the Group of Seven or other modernists, Russell's work, his institutional leadership, and his collaborations, notably with architect William S. Maxwell, contribute to a fuller understanding of the Canadian art world during a period of significant growth and transition. His paintings, such as "Kicking Horse Pass," "Beaver Valley, Selkirk Mountains," and "The Hermit Range," remain as testaments to his engagement with the Canadian landscape, and his career provides a valuable perspective on the artistic currents that shaped Canadian art before the dominance of modernism. He was part of a generation of artists, including figures like Wyly Grier and Edmund Morris, who upheld and disseminated artistic traditions while Canada was forging its cultural identity.