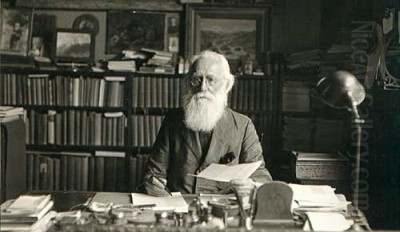

Thomas Mower Martin stands as a foundational figure in the history of Canadian art. Often affectionately referred to as the "Father of Canadian Art," and sometimes the "Dean of Canadian Art," his long and prolific career spanned a crucial period of Canada's development as a nation and the establishment of its artistic identity. Born in London, England, in 1838, Martin immigrated to Canada in 1862, bringing with him European sensibilities that he would adapt to capture the unique grandeur and rugged beauty of his adopted homeland. He passed away in Toronto in 1934, leaving behind a significant body of work and a legacy intertwined with the very institutions that came to define Canadian art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Martin's journey was not initially set towards an artistic career. His contributions primarily lie in landscape painting, but he was also adept at depicting animals, still lifes, and occasionally portraits, working proficiently in oil, watercolour, and etching. His dedication to portraying the Canadian scene, particularly its vast wilderness, helped shape both domestic and international perceptions of the country. He was instrumental in founding key art organizations and played a role in art education, solidifying his importance beyond his own canvases.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in London

Thomas Mower Martin was born into a well-connected London family in 1838. His father held the position of Recorder at the Inner Temple, placing the young Martin in an environment acquainted with legal and literary figures of the day. This background likely provided him with a solid general education, though his formal schooling initially pointed towards a military path. He attended a military school in Enfield, suggesting expectations perhaps lay in service rather than the arts.

However, an artistic inclination began to surface. Martin pursued studies in drawing and painting at the South Kensington Schools in London. This institution, later part of the Royal College of Art, was a significant centre for art and design education. It was here, sources suggest, that he received some guidance in watercolour techniques from artists referred to as the Humphreys, nurturing his burgeoning interest. Despite this formal instruction and his evident talent, Martin largely considered himself self-taught, developing his skills through observation and practice.

A significant personal event occurred when Martin was orphaned at the age of fifteen. He went to live with an aunt, a transition that must have profoundly impacted his youth. Despite these challenges and the initial leanings towards a military life, his passion for art continued to grow. London, as a major global art centre, would have exposed him to a wide range of artistic styles and influences, from the detailed realism of the Pre-Raphaelites to the atmospheric landscapes of J.M.W. Turner, though Martin's own style would develop along more traditional, descriptive lines.

The decision to leave England marked a pivotal moment. In 1862, at the age of 24, Martin, along with his wife Emma Nicolls (whom he had married prior to emigrating), set sail for Canada. Like many immigrants of the era, they were likely drawn by the promise of land and opportunity in the relatively young British colony. This move would irrevocably shift the focus of his life and art towards the landscapes of North America.

Arrival in Canada and Finding His Path

Upon arriving in Canada in 1862, Thomas Mower Martin initially sought to establish himself as a farmer. He purchased a 107-acre parcel of land in the Muskoka District of Ontario, a region known for its scenic lakes and forests but also for its challenging terrain. Martin's experience quickly bore this out. He discovered his property consisted largely of rock and swamp, entirely unsuitable for cultivation. This agricultural failure proved to be a blessing in disguise for Canadian art.

Faced with the inability to make a living from the land, Martin turned to his artistic talents. He began sketching and painting the surrounding Muskoka landscapes, capturing the unique character of the Canadian Shield – its rocky outcrops, dense woods, and reflective waters. This period was crucial in honing his skills and adapting his European-trained eye to the different light, colours, and forms of the Canadian environment. The necessity of earning a living spurred him towards becoming a professional artist.

He and his growing family eventually relocated, settling near Toronto, which was rapidly emerging as the cultural and economic hub of Ontario. This move placed Martin closer to potential patrons, fellow artists, and developing art institutions. He dedicated himself fully to painting, establishing a studio and beginning to build a reputation. His subjects expanded beyond Muskoka to include the gentler landscapes of Southern Ontario, as well as animal studies and still lifes, showcasing his versatility.

The transition from aspiring farmer to professional artist was complete. His early Canadian works began to attract attention, reflecting a detailed, realistic approach combined with a sensitivity to the atmosphere of the wilderness. This period laid the groundwork for his later, more extensive explorations of the Canadian landscape and his significant contributions to the country's burgeoning art scene. His personal experience of the Muskoka wilderness likely instilled in him a deep appreciation for the untamed aspects of Canada that would become a recurring theme in his work.

A Prolific Landscape Painter

Thomas Mower Martin's reputation rests primarily on his extensive output as a landscape painter. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the specific details of the Canadian environment, rendering trees, rocks, water, and atmospheric conditions with careful precision. His style remained largely rooted in the realistic traditions popular in the 19th century, favouring accurate depiction over impressionistic or abstract interpretations. This fidelity to nature resonated with audiences eager to see the vastness and variety of their country represented.

He worked confidently in both oil and watercolour. His oils often possess a richness and depth, allowing for detailed rendering of textures and forms, particularly effective in his depictions of forest interiors or mountainous terrains. His watercolours, often used for sketches made during his travels but also for finished works, demonstrate a lighter touch, capturing the transient effects of light and atmosphere on lakes, rivers, and skies. Martin also practiced etching, creating prints that allowed for wider dissemination of his images.

His subject matter was diverse, reflecting his extensive travels across Canada. While his early work focused on Ontario, particularly the Muskoka region and Southern Ontario pastorals, his horizons expanded significantly. He became particularly renowned for his paintings of the Canadian Rockies, capturing their majestic peaks, glaciers, and turquoise lakes. He also painted the Prairies, the Pacific Coast, and even ventured into the Arctic, demonstrating an adventurous spirit and a desire to document the full breadth of the Canadian landscape.

Beyond pure landscapes, Martin frequently incorporated wildlife into his scenes, depicting deer, moose, bears, and birds within their natural habitats. These were not mere accessories but often integral parts of the composition, reflecting his interest in natural history and adding a dynamic element to his work. He also produced dedicated animal studies and still life paintings, often featuring game or fish, which further showcased his technical skill and observational powers. His commitment to realism made his works valuable documents of Canada's natural heritage during a period of significant change.

The Canadian Pacific Railway Connection

A significant chapter in Thomas Mower Martin's career involved his association with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). In the late 19th century, the CPR played a crucial role not only in physically uniting Canada from coast to coast but also in promoting the country, particularly its western territories, to attract immigrants and tourists. Part of this promotional effort involved commissioning artists to travel along the railway lines and capture the scenic wonders, especially the dramatic landscapes of the Rocky Mountains.

Martin was among the first artists to benefit from this patronage, undertaking trips to Western Canada sponsored by the CPR, particularly between 1887 and the early 1900s. These journeys provided him with unparalleled access to regions previously difficult to reach. Armed with sketchbooks and painting materials, he documented the awe-inspiring vistas encountered along the railway route – towering peaks, cascading waterfalls, expansive glaciers, and pristine mountain lakes in areas like Banff and Lake Louise.

His paintings resulting from these trips became powerful advertisements for the railway and for Canada itself. They were exhibited, reproduced as illustrations, and sometimes used directly in CPR promotional materials. Martin's detailed and often romanticized depictions of the Rockies helped shape the popular image of the Canadian West as a land of sublime natural beauty, encouraging tourism and settlement.

He was not alone in this endeavour. The CPR sponsored several other prominent artists of the era, creating a unique body of work focused on the western landscape. Figures like Lucius O'Brien (who also served as the first president of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts), John Arthur Fraser, Frederic Marlett Bell-Smith, and Marmaduke Matthews also traveled under CPR auspices, each bringing their own style to the task. Martin's contributions stand out for their clarity, detail, and consistent focus on capturing the specific character of the mountain environment. This railway patronage was instrumental in broadening Martin's subject matter and cementing his reputation as a painter of the grand Canadian landscape.

Founding Father: Shaping Canadian Art Institutions

Thomas Mower Martin's influence extended far beyond his own artistic production; he was a key figure in establishing the institutional framework for art in Canada, particularly in Ontario. Recognizing the need for artists to organize, exhibit collectively, and promote professional standards, he became involved in the formation of crucial arts bodies during a period of growing national consciousness following Confederation in 1867.

In 1872, Martin was a driving force and founding member of the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA). This organization quickly became the leading venue for artists in the province, holding regular exhibitions, fostering camaraderie, and advocating for the visual arts. The OSA provided a vital platform for Martin and his contemporaries, like John Arthur Fraser, Marmaduke Matthews, Robert Ford Gagen, and James Griffiths, to showcase their work and engage with the public. Martin remained actively involved with the OSA for many years.

His commitment to art education led to his appointment as the first Director of the Ontario Government Art School in Toronto from 1877 to 1879. This institution, which eventually evolved into the Ontario College of Art and Design University (OCADU), was established to provide formal training for aspiring artists and designers. Martin's leadership during its formative years helped set its initial direction, emphasizing foundational skills in drawing and painting.

Perhaps his most significant institutional contribution came in 1880 when he became one of the charter members of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA), founded under the patronage of the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, and his wife, Princess Louise. The RCA aimed to establish a national body of professional artists, modelled after the Royal Academy in London. Its founding members included prominent artists from across the country, such as Lucius O'Brien (its first president), Robert Harris (famous for painting the Fathers of Confederation), Allan Edson, Henry Sandham, Otto Jacobi, and Napoleon Bourassa. Martin's inclusion underscored his established reputation and his commitment to professionalizing the arts in Canada. These institutions played a critical role in fostering a distinct Canadian art scene, and Martin was central to their creation.

Mentorship and Contemporaries

While largely self-taught, Thomas Mower Martin did engage in teaching and interacted extensively with the artistic community of his time. His role as the first Director of the Ontario Government Art School indicates a formal commitment to art education. Furthermore, some sources suggest that during his time teaching at the Art Association of Montreal (the precursor to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), his students included notable figures like Lucius O'Brien and John Colin Forbes. If accurate, this places Martin in a direct mentorship role with artists who would become significant in their own right – O'Brien as a leading landscape painter and president of the RCA, and Forbes as a renowned portraitist.

Beyond any formal teaching, Martin's position as a founder of both the OSA and the RCA placed him at the centre of the Canadian art world. He worked alongside, exhibited with, and undoubtedly influenced and was influenced by a wide circle of contemporaries. This network included the aforementioned founders like O'Brien, Fraser, Harris, Jacobi, Sandham, Matthews, and Edson, but also other important painters active during his long career.

These contemporaries included figures such as Frederic Arthur Verner, known for his depictions of Plains Indigenous peoples and buffalo; Homer Watson, whose landscapes of the Doon region of Ontario earned international acclaim; William Brymner, an influential teacher and painter based in Montreal; George Agnew Reid, known for his large-scale figurative works and murals, and also a principal of the Ontario College of Art; and Frances Anne Hopkins, famous for her depictions of voyageur canoe travel.

Martin's realistic style was shared by many of his contemporaries, particularly in the earlier part of his career, reflecting the prevailing tastes of the Victorian era. While later movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism began to influence younger Canadian artists towards the end of Martin's life (such as the members of the Group of Seven, whose approach differed markedly from Martin's), Martin remained steadfast in his detailed, descriptive approach. His career provides a valuable link between the colonial art traditions and the development of a distinctly Canadian school of painting, interacting with multiple generations of artists.

Notable Works and Recognition

While specific paintings by Thomas Mower Martin are numerous and held in various collections, perhaps his most widely recognized contribution in published form is the book Canada, published in London in 1907. This volume featured 77 full-colour reproductions of his paintings, accompanied by text written by the Canadian poet Wilfred Campbell. The book served as a visual celebration of the Dominion, showcasing landscapes from across the country, particularly the majestic scenery of the West that Martin had captured during his CPR-sponsored travels. Canada brought Martin's vision of the nation to a broad audience, both domestically and internationally, solidifying his reputation as a preeminent painter of the Canadian scene.

He also illustrated other publications, including a book titled Kew Gardens. His work was frequently exhibited throughout his career at the annual shows of the OSA and RCA, as well as at major international exhibitions, including the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in London (1886) and the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago (1893). This exposure helped build his reputation outside of Canada.

Martin's paintings were acquired by prominent collectors and institutions during his lifetime and after. Today, his works are held in major Canadian collections, including the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. His paintings were also appreciated by royalty; Queen Victoria acquired some of his work, and pieces are reportedly held in the Royal Collection at Windsor Castle.

His long career and foundational role earned him considerable respect within the Canadian art community, leading to the honorific titles "Dean" or "Father" of Canadian Art. While artistic tastes evolved, and his detailed realism might have seemed conservative compared to later modernist movements, the historical significance and technical proficiency of his work remain acknowledged. He successfully captured the spirit of an era and the visual identity of a nation in formation.

Personal Life and Later Years

Thomas Mower Martin's personal life was anchored by his long marriage to Emma Nicolls. They married in England before emigrating to Canada in 1862 and together raised a large family of nine children. Family life undoubtedly formed a backdrop to his busy artistic career, providing stability and perhaps influencing his choice of subjects at times, though his primary focus remained the landscape. The demands of supporting a large family likely fueled his prolific output and his willingness to undertake commissions and sponsored travel.

After the initial challenging years in Muskoka, the family settled in Toronto, which remained Martin's base for the rest of his life. He maintained a studio in the city and was an active participant in its cultural life through his involvement with the OSA and RCA. His home and studio would have been gathering places for artists and patrons, reflecting his central position in the Toronto art scene.

He continued to paint and exhibit well into his later years, remaining productive even as new artistic styles emerged. His extensive travels across Canada provided him with a vast reservoir of sketches and memories to draw upon for studio paintings. He witnessed significant changes in Canada during his lifetime, from the Confederation era through the expansion into the West, the Klondike Gold Rush, World War I, and the societal shifts of the early 20th century. His art, however, largely remained focused on the enduring beauty and power of the natural landscape.

Thomas Mower Martin passed away in Toronto in 1934 at the venerable age of 96. His long lifespan allowed him to witness the full arc of 19th-century Canadian art and the beginnings of 20th-century modernism. His death marked the end of an era for Canadian painting. In 1944, a significant collection of his personal papers, sketches, and records was deposited with the Public Archives of Canada (now Library and Archives Canada), providing valuable insight into his life, career, and the artistic milieu in which he worked.

Legacy and Assessment

Thomas Mower Martin's legacy in Canadian art history is multifaceted. As a painter, he was incredibly prolific, creating a vast body of work that documented the Canadian landscape from coast to coast with meticulous detail and sincere appreciation. His paintings, particularly those of the Rocky Mountains and the Muskoka region, helped define the visual identity of Canada for both Canadians and international audiences during a critical period of nation-building. His realistic style, while perhaps falling out of favour with the rise of modernism, appealed greatly to the tastes of his time and remains admired for its technical skill and descriptive power.

Equally important was his role as an institution builder. As a founding member of both the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, and as the first director of what would become OCAD University, Martin played an indispensable part in creating the structures that supported the professionalization and development of art in Canada. These organizations provided vital platforms for exhibition, education, and advocacy, fostering generations of Canadian artists.

His travels, especially those sponsored by the Canadian Pacific Railway, not only provided him with rich subject matter but also contributed to the broader cultural project of promoting Canadian expansion and tourism. He, along with contemporaries like Lucius O'Brien and F.M. Bell-Smith, helped create the iconic imagery of the Canadian West that persists to this day.

While later artists, notably Tom Thomson and the Group of Seven, would offer more stylized and emotionally charged interpretations of the Canadian landscape, Martin's work represents a crucial earlier phase. He captured the wilderness with the eye of a dedicated observer, combining Victorian sensibilities with a genuine connection to his adopted country. The title "Father of Canadian Art," though perhaps overlooking earlier figures and Indigenous traditions, reflects the deep respect he commanded and his foundational contributions during the formative years of Canada's professional art scene. His work remains a valuable record of Canada's natural heritage and a testament to a long and dedicated artistic career.

Conclusion

Thomas Mower Martin occupies a significant and respected place in the annals of Canadian art. From his arrival as an immigrant with failed farming aspirations to his death as a celebrated painter and institutional founder, his life mirrored the growth and development of Canada itself. His dedication to capturing the diverse landscapes of his adopted country, rendered with detailed realism and evident affection, provided a visual narrative for a young nation. Through his tireless work as an artist, his pioneering travels, and his crucial role in establishing the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Martin laid essential groundwork for the future of Canadian art. He remains a pivotal figure, a true chronicler of the Canadian wilderness whose influence and contributions continue to be recognized.