Georgios Jakobides stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of modern Greek art, a painter whose career bridged the 19th and 20th centuries and whose influence resonated deeply within his homeland and beyond. Born into a world where Greece was forging its modern identity, Jakobides became a leading exponent of the Munich School, a movement that profoundly shaped Greek artistic expression. His dedication to academic realism, his celebrated depictions of childhood, and his instrumental role in establishing national art institutions secure his legacy as a cornerstone of Greek cultural heritage.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Greece

Georgios Jakobides was born on January 11, 1853, in Chidira, a village on the island of Lesbos, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire. His early years were spent in a region rich with ancient history and burgeoning with a renewed sense of Hellenic identity. Seeking broader opportunities, the young Jakobides moved to Smyrna (modern-day Izmir), a vibrant cosmopolitan port city with a significant Greek population, for his initial education. It was here that his artistic inclinations likely began to surface.

The pivotal moment in his early artistic development came when he relocated to Athens, the capital of the newly independent Greek kingdom. Between 1870 and 1876, Jakobides enrolled at the Athens School of Fine Arts (then known as the School of Arts). This institution, though relatively young, was the crucible for aspiring Greek artists. During these formative years, he studied both painting and sculpture, gaining a foundational understanding of classical forms and academic techniques.

A key figure in his Athenian education was Nikiforos Lytras (1832-1904), one of the most important Greek painters of the 19th century and himself a product of the Munich Academy. Lytras, along with Nikolaos Gyzis (1842-1901), was a leading proponent of the Munich School in Greece, and his teachings would have undoubtedly exposed Jakobides to the tenets of German academic realism, emphasizing meticulous draughtsmanship, historical and genre subjects, and a polished finish. Lytras's influence likely steered Jakobides towards a career in painting and instilled in him the academic rigor that would define his oeuvre.

The Munich Years: Forging a Style at the Academy

In 1877, Jakobides' talent was recognized with a scholarship that enabled him to pursue advanced studies abroad. Like many ambitious Greek artists of his generation, he chose Munich, the capital of Bavaria, which had become a major European art center, rivaling Paris in its academic prestige. He enrolled in the prestigious Munich Academy of Fine Arts (Akademie der Bildenden Künste München), where he would spend the next seventeen crucial years of his life, from 1877 to 1900.

At the Munich Academy, Jakobides studied under some of the most renowned artists and teachers of the era. Among his professors was Karl Theodor von Piloty (1826-1886), a celebrated historical painter whose grand, dramatic compositions and meticulous attention to detail were highly influential. Piloty's studio attracted students from across Europe and America, and his emphasis on historical accuracy and theatrical staging left a mark on Jakobides. Other influential teachers included Wilhelm von Lindenschmit the Younger (1829-1895), also known for historical scenes, and Ludwig von Löfftz (1845-1910), who was respected for his genre paintings and portraits, and his mastery of light and shadow.

Living and working in Munich, Jakobides was immersed in an artistic environment dominated by academic realism. This style, characterized by its precise representation of subjects, often drawn from history, mythology, or everyday life, was the prevailing aesthetic. He diligently honed his skills, producing works that included mythological scenes, genre paintings (scenes of everyday life), and portraits. His technique became increasingly refined, marked by strong drawing, balanced compositions, and a rich, often dark, palette typical of the Munich School. During this period, he also established his own studio in Munich in 1883, indicating his growing professional standing.

The Munich School, as it pertained to Greek artists, was not merely an adopted style but a significant cultural phenomenon. Artists like Theodoros Vryzakis (1814-1878), an earlier pioneer, had already established a Greek presence there. Jakobides, alongside contemporaries like Gyzis and Konstantinos Volanakis (1837-1907), who specialized in seascapes, formed a core group of Greek artists who absorbed German academicism and adapted it to Hellenic themes or universal human experiences. Other Greek artists associated with or influenced by the Munich milieu included Polychronis Lembesis (1848-1913) and Symeon Savvidis (1859-1927).

The Painter of Childhood: A Defining Theme

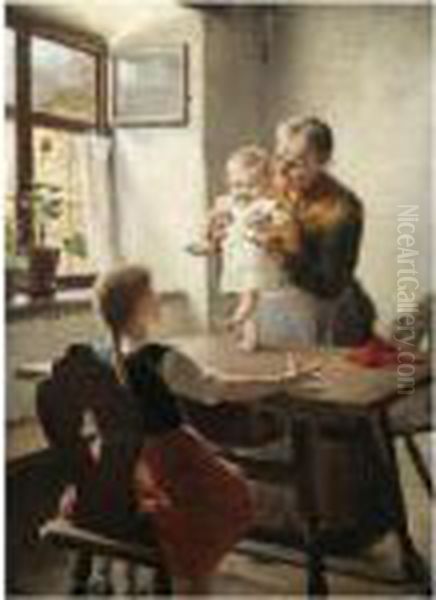

While in Munich, Georgios Jakobides developed a particular affinity for a subject that would become his hallmark: the world of children. He gained widespread recognition and acclaim for his tender and insightful portrayals of children in various everyday situations. These works moved away from grand historical or mythological narratives towards more intimate, sentimental, and universally relatable scenes. His ability to capture the innocence, playfulness, and sometimes melancholic introspection of childhood earned him the affectionate epithet, "the painter of childhood."

His paintings often depicted children at play, interacting with family members (especially grandparents), or engrossed in simple activities. These scenes were rendered with meticulous detail, a warm palette, and a sensitive understanding of child psychology. He masterfully used light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create a sense of volume and atmosphere, often imbuing his subjects with a gentle, almost palpable presence. The textures of fabrics, the softness of a child's skin, and the specific details of domestic interiors were all rendered with remarkable skill.

This focus on genre scenes, particularly those involving children, resonated with the bourgeois tastes of the late 19th century, which valued sentimentality and depictions of domestic virtue. However, Jakobides' works often transcended mere sentimentality through their keen observation and psychological depth. He avoided overt idealization, instead presenting children with a naturalism that was both charming and believable.

Return to Greece: A National Role in Art

After seventeen successful years in Munich, where he had established a strong reputation and participated in numerous exhibitions, Georgios Jakobides was called back to Greece in 1900. The invitation reportedly came from King George I himself, a testament to the esteem in which he was held. His return marked a new chapter in his career, one focused on contributing to the artistic infrastructure and education of his homeland.

One of his most significant contributions was his instrumental role in the founding of the National Gallery of Greece in Athens. He became its first curator or director, a position he held from its inception in 1900 until 1918. In this capacity, he was responsible for shaping the early collection, organizing exhibitions, and establishing the gallery as a key institution for the preservation and promotion of Greek art. His leadership was crucial in laying the groundwork for what would become the country's foremost art museum.

Concurrently with his work at the National Gallery, Jakobides also took on a prominent role in art education. In 1904, he was appointed as a professor of oil painting at the Athens School of Fine Arts, the very institution where he had begun his artistic journey. He taught there for twenty-five years, until 1929, influencing a new generation of Greek artists. His teaching would have emphasized the academic principles he had mastered in Munich – strong drawing, compositional harmony, and a respect for traditional techniques. Among the many students who passed through the Athens School of Fine Arts during his tenure, some would go on to explore different artistic paths, such as the notable naive painter Theophilos Hatzimihail (c. 1870-1934), though Theophilos's style was distinctly different from academic norms.

Artistic Philosophy and Opposition to Modernism

Georgios Jakobides remained a staunch advocate of academic realism throughout his career. His artistic philosophy was rooted in the traditions of the Munich School, emphasizing technical skill, verisimilitude, and often, a narrative or anecdotal element in his paintings. His style was characterized by its clear forms, careful modeling, rich colors (though sometimes somber in the Munich tradition), and a polished finish. He excelled in capturing the play of light and creating a sense of depth and volume.

As artistic movements like Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and early modernism (such as Fauvism and Cubism) began to gain traction in Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jakobides remained largely resistant to these new trends. He, like many academic painters of his generation, viewed these emerging styles as a departure from the established principles of good draftsmanship and a perceived decline in artistic standards. His commitment was to the representational art that he believed best conveyed human emotion and narrative.

This conservative stance was not uncommon among artists of the Munich School, which, by the turn of the century, was seen by some as an established, if somewhat old-fashioned, bastion against the avant-garde. While artists in Paris like Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) were revolutionizing painting with their focus on light and fleeting moments, Jakobides continued to work within the academic framework. His German contemporary, Fritz von Uhde (1848-1911), while also trained in a traditional manner, began to incorporate Impressionistic light and color into his religious and genre scenes, showing a path of synthesis that Jakobides did not fully embrace. Similarly, the German realist Wilhelm Leibl (1844-1900), though not an Impressionist, focused on an unvarnished portrayal of peasant life that differed from Jakobides' more sentimental genre scenes.

Notable Works and Their Characteristics

Georgios Jakobides produced a significant body of work during his long career. Many of his most beloved paintings feature children and domestic scenes, showcasing his characteristic style and thematic concerns.

_The Naughty Grandson_ (or _Grandpa's Naughty Boy_) (c. 1884-1886): This is one of his most famous and reproduced works. It depicts an elderly man, presumably a grandfather, attempting to work or read while a mischievous young boy playfully disrupts him, perhaps tugging at his beard or climbing on his back. The painting beautifully captures the affectionate exasperation of the grandfather and the innocent exuberance of the child. The details of the room, the textures of clothing, and the expressive faces are rendered with great skill.

_The First Steps_ (c. 1889-1892): Another iconic piece, this painting portrays a tender family moment: a young child taking its first tentative steps, supported by an older sibling or parent, while other family members look on with encouragement and joy. The scene is filled with warmth and familial love, a common theme in Jakobides' work. The interplay of light, often from a window, illuminates the figures and creates a gentle, domestic atmosphere.

_Children's Concert_ (or _Family Recital_) (c. 1894-1900): This work shows a group of children engaged in a playful musical performance in a well-appointed interior. One child might be "conducting" while others play toy instruments or sing. It exemplifies Jakobides' ability to create lively, multi-figure compositions that tell a story and evoke the imaginative world of childhood.

_Cold Shower_ (or _The Cold Bath_): This painting typically depicts a child, often a young boy, reacting with surprise or discomfort to a stream of cold water, perhaps during a bath. It's a scene that combines humor with a realistic portrayal of a child's sensory experience. The rendering of the child's body and the glistening water showcases Jakobides' technical prowess.

_Grandmother’s Favorite_: Similar to _The Naughty Grandson_, this theme often explores the special bond between grandparents and grandchildren. Such paintings would depict a grandmother doting on a child, perhaps telling a story or sharing a quiet moment.

_The Flower Seller_: While best known for his child-centric scenes, Jakobides also painted other genre subjects. A work like _The Flower Seller_ would depict a scene from everyday street life, allowing him to explore different character types and social settings, though still with a focus on human interaction and detailed realism.

His portraits, though perhaps less famous than his genre scenes, were also accomplished, demonstrating his ability to capture a sitter's likeness and character. He also painted some mythological subjects, particularly earlier in his career, in line with the academic training he received.

Awards, Exhibitions, and International Recognition

Georgios Jakobides' talent did not go unnoticed during his lifetime. He received numerous awards and accolades, both in Greece and internationally, underscoring his status as a significant artist.

His works were frequently exhibited in prestigious venues. He participated in international exhibitions in:

Berlin (1891): Where he received an award.

Paris (1900): At the Exposition Universelle, a major international showcase, where he also won an award (a gold medal).

Other exhibitions included those in Munich, Athens, Bremen, and Rome.

Some of the specific honors he received include:

A gold medal in Athens (1888).

The "Award of Excellence in Arts and Letters" from the Greek state.

He was made an Officer of the Order of the Redeemer by the Greek state.

The Academy of Athens awarded him the "Excellence in Arts and Letters" prize in 1926.

His paintings were sought after by collectors and institutions. Today, his works are prominently featured in the National Gallery of Greece in Athens, the Averoff Gallery in Metsovo, the Leventis Gallery in Nicosia, Cyprus, and in numerous private collections and museums worldwide. The continued appreciation for his art is a testament to its enduring appeal.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Georgios Jakobides passed away in Athens on December 13, 1932, at the age of 79. He left behind a rich artistic legacy and an indelible mark on the development of modern Greek art. His influence can be seen in several areas:

Champion of Academic Realism: He was one of the foremost Greek exponents of the Munich School and academic realism. While later generations of artists would embrace modernism, Jakobides' work represents a high point of academic achievement in Greek art.

The Painter of Childhood: His sensitive and insightful portrayals of children remain his most celebrated contribution, creating a genre within Greek painting that was both popular and artistically respected.

Institution Builder: His role as the first director of the National Gallery of Greece was crucial in establishing a national institution dedicated to preserving and promoting Greek art.

Educator: As a long-serving professor at the Athens School of Fine Arts, he directly influenced generations of Greek artists, transmitting the technical skills and artistic values of the academic tradition. Even those who later diverged from his style would have benefited from the rigorous training.

Cultural Icon: His paintings, particularly those of children and family life, have become iconic images in Greece, widely reproduced and cherished for their warmth, sentimentality, and technical brilliance.

In recognition of his importance, the Jakobides Digital Museum was established in his birthplace, Chidira, Lesbos. Opened in 2007, it is Greece's first fully digital art museum. It uses interactive digital technologies to present his life and work, allowing visitors to explore his paintings in detail, learn about his biography, and understand his artistic context. This innovative approach helps to keep his legacy alive and accessible to new generations.

His son, the actor Michalis Iakovides (Michael Jakobides), also played a role in preserving his father's legacy, notably by donating a significant part of his father's personal archives and potentially some artworks to state institutions after the painter's death.

Conclusion: A Pillar of Greek Artistic Identity

Georgios Jakobides was more than just a skilled painter; he was an artist who captured the ethos of his time while contributing significantly to the cultural infrastructure of modern Greece. His journey from the island of Lesbos to the art academies of Athens and Munich, and back to a leading role in his nation's artistic life, is a story of talent, dedication, and profound impact.

While artistic tastes have evolved, and the avant-garde movements he resisted have long since become part of the art historical canon, Jakobides' work retains its power and charm. His meticulous technique, his empathetic portrayal of human relationships, especially the world of childhood, and his dedication to the principles of academic art ensure his enduring place as a master of 19th and early 20th-century Greek painting. He remains a beloved figure, whose art continues to speak to audiences with its timeless themes of family, innocence, and the quiet beauty of everyday life, firmly establishing him as a pillar of Greek artistic identity. His connection to the broader European tradition through the Munich School, and his specific contributions to the Greek national scene, make him a fascinating subject for art historical study and appreciation.