Gerard ter Borch the Younger (1617-1681) stands as one of the most refined and influential painters of the Dutch Golden Age. Flourishing during the 17th century, a period of extraordinary artistic output in the Netherlands, Ter Borch carved a unique niche for himself within the Baroque movement. He is celebrated primarily for his exquisite interior genre scenes and his psychologically astute portraits, which capture the quiet elegance and burgeoning prosperity of the Dutch middle and upper classes. His work is distinguished by an unparalleled sensitivity to texture, a subtle command of light and color, and a profound understanding of human interaction and inner life.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born in Zwolle, in the province of Overijssel, Gerard ter Borch was immersed in art from a young age. His father, Gerard ter Borch the Elder, was himself an artist and also held the position of a tax official, ensuring a comfortable and cultured environment for his children. The elder Ter Borch recognized and encouraged his son's talent early on, providing initial instruction. This familial support was crucial in shaping the young artist's path. Several siblings, notably his half-sister Gesina ter Borch, also pursued artistic endeavors, creating a dynamic creative household.

Seeking more formal training, the young Ter Borch traveled first to Amsterdam around 1632. While the exact nature of his studies there remains somewhat speculative, it's believed he may have spent time in the workshops of artists known for their guardroom scenes and small-figure compositions, possibly Willem Cornelisz. Duyster or Pieter Codde. These artists specialized in depicting soldiers and social gatherings, themes that Ter Borch would later adapt with greater refinement.

His training continued in Haarlem, a major artistic center, beginning around 1634. There, he became a pupil of the landscape painter Pieter de Molijn. Although Ter Borch's mature work shows little direct stylistic debt to Molijn's landscapes, the experience in Haarlem was significant. It was likely during this period that he absorbed the influence of the city's most famous resident, the great portraitist Frans Hals. While Ter Borch never adopted Hals's bravura brushwork, Hals's ability to capture lively expressions and the presence of his sitters may have left an impression. In 1635, Ter Borch was admitted into the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke, formally marking his status as an independent professional artist.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Ter Borch embarked on extensive travels to broaden his artistic education and seek patronage. Around 1635, shortly after joining the Haarlem guild, he journeyed to London. This visit was particularly significant as it likely brought him into contact with the work, and possibly the person, of Sir Anthony van Dyck, the leading court painter in England. Van Dyck's elegant, aristocratic portrait style, characterized by refined poses, luxurious fabrics, and an air of sophisticated grace, appears to have deeply influenced Ter Borch. The increased elegance and refinement seen in Ter Borch's subsequent work likely owe a debt to his English sojourn.

His travels did not end there. Over the next few years, he visited Italy and Spain, absorbing the artistic traditions of Southern Europe. In Rome, between 1640 and 1641, he is known to have created portrait etchings, including depictions of Jan Six (a prominent Amsterdam figure later famously painted by Rembrandt) and an unidentified gentleman. His time in Spain brought him to the court in Madrid, where he reportedly gained recognition and even met King Philip IV. However, according to some accounts, court intrigues compelled him to leave Spain and return to the Netherlands. These diverse experiences exposed Ter Borch to different artistic styles, patrons, and cultures, enriching his perspective and contributing to the sophisticated, cosmopolitan air that distinguishes his paintings.

Artistic Style: Elegance and Observation

Gerard ter Borch developed a highly distinctive style characterized by meticulous technique, subtle observation, and an atmosphere of quiet refinement. He excelled in both genre painting and portraiture, bringing a unique sensibility to each.

Genre Painting: Scenes of Quiet Intimacy

Ter Borch is perhaps best known for his genre scenes, which typically depict members of the Dutch upper-middle class in domestic interiors. Unlike the boisterous tavern scenes of Jan Steen or Adriaen Brouwer, Ter Borch's works focus on moments of quiet contemplation, polite social interaction, or private activities. His subjects are often shown engaged in reading letters, making music, conversing, or performing their toilette. These scenes are imbued with a sense of decorum and restraint, yet often contain subtle psychological undercurrents and narrative ambiguity.

He masterfully used composition and light to create intimate, focused spaces. Figures are often placed in sparsely furnished but elegant rooms, drawing the viewer's attention to their interactions and expressions. His handling of light is typically soft and nuanced, illuminating key figures and objects while allowing surrounding areas to recede into shadow, enhancing the sense of privacy and introspection. The narratives are rarely explicit; instead, Ter Borch invites viewers to interpret the subtle glances, gestures, and relationships between the figures, creating scenes rich in suggestion and quiet drama.

Portraiture: Refined Likenesses

Ter Borch's portraits share the refinement and psychological acuity of his genre scenes. He often worked on a relatively small scale, creating intimate likenesses rather than grand public statements. His sitters, usually members of the prosperous merchant class or local dignitaries, are presented with an air of calm dignity. He avoided overt flattery, instead focusing on capturing a truthful likeness while conveying the sitter's social standing through their posture, clothing, and reserved demeanor.

His palette in portraiture was often restrained, dominated by blacks, whites, grays, and subtle earth tones, which allowed the meticulously rendered textures of clothing and the delicate modeling of faces and hands to take center stage. Backgrounds are typically dark and plain, further concentrating attention on the sitter. This approach resulted in portraits that are both elegant and introspective, conveying a sense of the individual's inner life beneath the composed exterior. His ability to capture personality with such subtlety places him among the leading portraitists of the era, alongside figures like Rembrandt van Rijn, though Ter Borch's style remained distinctly more reserved and polished.

Mastery of Texture

A hallmark of Gerard ter Borch's art is his extraordinary ability to render textures, particularly fabrics. He is renowned for his depictions of satin, silk, velvet, wool, and lace. His rendering of white satin, in particular, is considered unparalleled. He achieved these effects through incredibly fine, almost invisible brushwork, carefully modulating tones and highlights to capture the precise way light reflects off different surfaces. The shimmering sheen of silk, the soft depth of velvet, the crispness of linen, and the intricate patterns of lace are all rendered with breathtaking verisimilitude.

This technical virtuosity was not merely for show; it served to enhance the realism of his scenes and underscore the wealth and status of his subjects. The luxurious materials depicted were markers of the prosperity enjoyed by the Dutch elite during the Golden Age. Ter Borch's meticulous attention to these details contributes significantly to the overall sense of elegance and refinement that pervades his work, influencing contemporaries like Gabriel Metsu and Frans van Mieris the Elder, who also specialized in highly finished depictions of upper-class life.

Key Works and Themes

Ter Borch's oeuvre, though not vast (estimated at around 80 surviving paintings), includes several masterpieces that exemplify his style and thematic concerns.

The Oath of Ratification of the Treaty of Münster (1648): This is perhaps Ter Borch's most famous work and a unique piece within his output. It is a historical group portrait depicting the solemn moment when Dutch and Spanish delegates swore an oath to uphold the treaty that ended the Eighty Years' War and formally recognized the independence of the Dutch Republic. Ter Borch himself witnessed the event in Münster's town hall and meticulously recorded the likenesses of the numerous participants. The painting is remarkable for its historical significance, its detailed portrayal of the dignitaries, and its sophisticated composition, capturing the gravity of the occasion with characteristic restraint.

Paternal Admonition (also known as Gallant Conversation) (c. 1654-1655): This iconic genre scene depicts a standing man addressing a seated young woman whose back is turned to the viewer, while another woman sips wine nearby. The young woman's shimmering white satin dress is a tour-de-force of textural painting. The exact subject has been debated for centuries – is it a father admonishing his daughter, or a suitor making a proposition in a brothel setting (as suggested by a coin in the man's hand in some versions)? This ambiguity, combined with the psychological tension and exquisite execution, makes it one of Ter Borch's most compelling works.

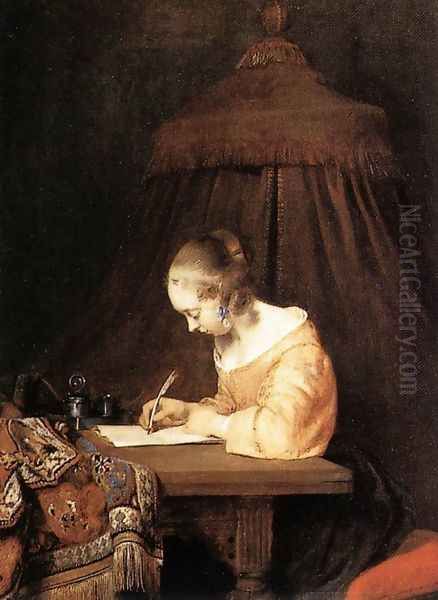

Woman Writing a Letter (c. 1655) and related works like The Letter (early 1660s) and Curiosity (c. 1660): Ter Borch frequently explored the theme of letter writing and reading, popular subjects in Dutch genre painting that often alluded to love, news from afar, or private thoughts. These paintings typically feature elegantly dressed women engrossed in their correspondence, often attended by messengers or companions. Works like Curiosity, showing one woman reading a letter while two others lean in eagerly, highlight themes of intimacy, privacy, and female social networks. The depiction of these private moments raised contemporary discussions about decorum and the inner lives of women.

The Music Lesson (c. 1658), The Concert (c. 1661-1662), and The Duet: Singer and Theorbo Player: Music-making was another favorite theme, often carrying connotations of harmony, courtship, and refined leisure. Ter Borch depicted individuals playing instruments like the lute, theorbo, or virginal, sometimes alone, sometimes in duets or small groups. These scenes allowed him to explore the interplay between figures, the textures of instruments and clothing, and the effects of interior light, often creating a romantic or contemplative mood. A Woman Playing a Theorbo for a Cavalier is another fine example of this theme.

Boy Delousing his Dog (c. 1670): This work shows a different facet of Ter Borch's genre painting, depicting a more humble, everyday scene with sensitivity and careful observation. It reflects an interest in the details of daily life across different social strata, although his primary focus remained on the elite.

Other notable works demonstrating his range include early pieces like Man on Horseback (1634), showing his skill with dynamic poses, genre scenes like The Knife Grinder's Family (1653) and The Suitor's Visit (1654), and fine portraits such as the Magistrates of Deventer (1667), Burgomaster Jan van Duren, and the poignant Posthumous Portrait of Moses ter Borch (1667), depicting his younger brother who had died serving in the navy.

Contemporaries and Influence

Gerard ter Borch operated within a vibrant artistic community. His training connected him with Pieter de Molijn and potentially Willem Duyster and Pieter Codde. His style reflects an awareness of Frans Hals and Anthony van Dyck. He was a contemporary of the towering figure of Dutch art, Rembrandt van Rijn, although their styles differed significantly – Rembrandt's dramatic chiaroscuro and expressive brushwork contrasting with Ter Borch's polished refinement.

Ter Borch's most significant impact was arguably on Johannes Vermeer. Several of Vermeer's compositions, themes (especially women in interiors engaged in quiet activities like reading letters or making music), and his interest in light effects seem indebted to Ter Borch's pioneering work in these areas. While Vermeer developed his own unique style, Ter Borch's influence is undeniable.

Other contemporaries who explored similar themes of elegant interior genre scenes include Pieter de Hooch, known for his complex spatial arrangements and light-filled courtyards; Gabriel Metsu, whose work often rivals Ter Borch's in refinement and detail; Jacob Ochtervelt, who also depicted upper-class domestic life; and Frans van Mieris the Elder, a leading figure of the Leiden 'fijnschilders' (fine painters) known for their meticulous technique. Nicolaes Maes, initially a genre painter influenced by Rembrandt, later turned to elegant portraiture somewhat akin to Ter Borch's style.

Ter Borch also played a role as a teacher. His most notable pupil was Caspar Netscher, who successfully adopted his master's refined style, particularly in small-scale portraiture, becoming a highly fashionable painter in his own right. Ter Borch's talented half-sister, Gesina ter Borch, was also an artist and frequently served as a model in his paintings, embodying the ideal of feminine grace central to his work.

Later Life and Legacy

In 1654, Gerard ter Borch settled in Deventer, another town in his native province of Overijssel. He married Geertruyt Matthys in the same year and became a respected citizen, eventually holding public office as a 'gemeensman' (common councilman). He continued to paint, producing some of his finest works during his Deventer period, including portraits of local dignitaries like the magistrates. He remained active as an artist until his death in Deventer in December 1681.

Despite his considerable success and influence, Ter Borch was perhaps less widely famous during his lifetime than some contemporaries. However, his reputation grew steadily after his death. His unique contribution lies in his elevation of genre painting to a level of unprecedented elegance and psychological subtlety. He perfected the art of depicting the textures of fine materials and captured the nuances of social interaction and private emotion with extraordinary sensitivity.

His influence, particularly on Vermeer, secured his place in art history. He offered a vision of Dutch Golden Age life that emphasized decorum, prosperity, and quiet introspection, complementing the more varied depictions offered by other masters. His work remains highly prized for its technical perfection, its serene beauty, and its insightful portrayal of human character.

Collections and Market Presence

Gerard ter Borch's meticulous technique meant his output was relatively limited. Today, only around 80 paintings are confidently attributed to him, making his works comparatively rare and highly valued. They are held in major museums around the world.

Significant holdings include:

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (housing around six works)

The Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (also with approximately six paintings)

The Louvre Museum, Paris (holding five works)

The Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden (with four paintings)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles (possessing three works)

The Wallace Collection, London (holding two significant examples)

The National Gallery, London, the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and the Mauritshuis, The Hague, also hold important paintings by Ter Borch.

His works occasionally appear on the art market, where they command high prices due to their rarity and quality. Historical auction records attest to their long-standing desirability. For instance, a version of The Messenger saw its price increase dramatically over the 18th and 19th centuries, reflecting growing appreciation. While specific auction results vary, paintings by Gerard ter Borch remain sought after by major collectors and institutions, cementing his status as a key master of the Dutch Golden Age whose intimate and elegant visions continue to captivate viewers centuries later.