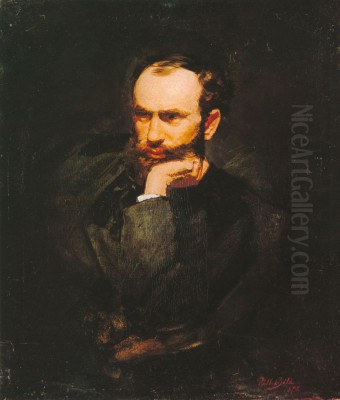

Geza Mészöly stands as a significant figure in the pantheon of 19th-century Hungarian art, celebrated for his evocative landscapes and sensitive portrayals of rural life. His work, imbued with a gentle melancholy and a profound connection to the Hungarian countryside, carved a unique niche that bridged academic traditions with emerging plein-air sensibilities. Mészöly's paintings are more than mere depictions; they are poetic interpretations of nature and the human presence within it, capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere with remarkable subtlety. His legacy endures not only in the canvases he left behind but also in his influence on subsequent generations of Hungarian artists who sought to define a national artistic identity through the depiction of their homeland.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born on May 18, 1844, in Sárbogárd, Hungary, Geza Mészöly's early life was set against the backdrop of a nation grappling with its identity within the Habsburg Empire. While detailed records of his childhood are scarce, it is understood that his artistic inclinations emerged at a young age. The vast plains and tranquil waters of the Hungarian landscape likely provided early inspiration, shaping his lifelong fascination with the natural world. His formal artistic education began not in Hungary, but in the prominent art centers of the era, a common path for ambitious artists from regions with less developed institutional art training.

Mészöly first journeyed to Vienna, enrolling in the Academy of Fine Arts. Vienna, as the imperial capital, offered a rigorous academic environment steeped in the traditions of European art. Here, he would have been exposed to the works of Old Masters and the prevailing academic styles that emphasized meticulous draftsmanship, balanced composition, and historical or mythological subject matter. This foundational training provided him with the technical skills essential for any aspiring painter of the time.

Following his studies in Vienna, Mészöly moved to Munich in 1869, another critical hub for artistic development in Central Europe. He joined the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied under notable figures such as Karl von Piloty, a leading historical painter. However, it was perhaps his association with landscape painters like Adolf Lier and, significantly, Albert Zimmermann, that proved more formative for his future direction. Zimmermann, known for his heroic landscapes, nonetheless encouraged a direct engagement with nature, a principle that Mészöly would increasingly embrace. The Munich school, while still rooted in academicism, was also experiencing the currents of Realism and a growing interest in landscape painting for its own sake.

The Evolution of a Distinctive Style

Upon returning to Hungary in the early 1870s, Mészöly began to synthesize the influences of his academic training with a more personal and direct observation of nature. His style gradually shifted from the stricter confines of academicism towards a more lyrical and atmospheric approach. He was particularly drawn to the Barbizon School painters of France, whose work he would have encountered through reproductions, exhibitions, or word of mouth. Artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Charles-François Daubigny, and Théodore Rousseau championed painting outdoors (en plein air) and sought to capture the transient effects of light and weather, imbuing their landscapes with a sense of mood and poetry.

Mészöly adopted a similar ethos. He became known for his depictions of the Hungarian landscape, particularly the areas around Lake Balaton and the Tisza River. His paintings often feature a characteristic haziness or mistiness, a soft, diffused light that lends his scenes an ethereal quality. This was not merely a stylistic quirk but a deliberate attempt to convey the specific atmospheric conditions of these regions and to evoke an emotional response in the viewer. His palette, while capable of richness, often favored subtle gradations of tone, particularly greys, blues, and earthy browns, contributing to the overall harmony and tranquility of his compositions.

A term sometimes associated with Mészöly and his circle is "agyagrealizmus" or "clay realism," reflecting a deep connection to the soil and the tangible reality of the Hungarian land. While he was a realist in his commitment to depicting recognizable scenes and figures, his realism was tempered by a romantic sensibility. He was less interested in the stark, unvarnished truth of a Gustave Courbet and more inclined towards a gentle, almost elegiac portrayal of his subjects. His figures, often peasants or fishermen, are integrated seamlessly into their surroundings, appearing as natural components of the landscape rather than heroic protagonists.

In the 1880s, his style became somewhat more informal, with a greater emphasis on capturing a specific mood or atmosphere. This later phase shows a closer affinity with the poetic naturalism of Corot, focusing on the overall impression rather than minute detail. His brushwork, while always controlled, could become looser, suggesting forms and textures rather than explicitly defining them.

The Hungarian Landscape as Muse

The Hungarian landscape was undoubtedly Geza Mészöly's primary muse. He possessed an intimate understanding of its varied terrains, from the expansive Puszta (Great Hungarian Plain) to the shimmering waters of its lakes and the winding paths of its rivers. He was particularly captivated by Lake Balaton, Central Europe's largest freshwater lake. Many of his paintings depict its shores, often under soft, overcast skies or in the gentle light of dawn or dusk. He captured the unique interplay of water, sky, and land, the reeds swaying in the breeze, and the distant, hazy outlines of hills.

The Tisza River, another recurring subject, offered different compositional possibilities. Mészöly painted its banks, its ferry crossings, and the life that unfolded along its course. These river scenes often convey a sense of quietude and timelessness, the slow-moving water reflecting the sky, the trees along the banks casting soft shadows. He was adept at rendering the subtle shifts in color and light that occur throughout the day and across the seasons, giving his landscapes a palpable sense of place and time.

His depictions of the Puszta, while perhaps less frequent than his water scenes, also hold significance. He captured the vastness of the plains, the characteristic draw-wells, and the herdsmen with their animals. These works often emphasize the horizontal expanse of the land, creating a feeling of openness and solitude. Through his dedicated focus on these native scenes, Mészöly contributed to the growing movement in Hungarian art that sought to establish a distinct national iconography, moving away from the universal themes favored by academic art towards subjects that resonated specifically with Hungarian identity and experience.

Depicting Rural Life with Empathy

Integral to Mészöly's landscapes are the figures that inhabit them. He primarily depicted peasants, fishermen, and herdsmen, individuals whose lives were intrinsically linked to the land and water. Unlike some contemporary genre painters who might sentimentalize or caricature rural figures, Mészöly approached his subjects with empathy and respect. His figures are typically engaged in their daily tasks – fishing, tending livestock, traveling along a country road – and are portrayed with a quiet dignity.

These figures are rarely the central focus in a dramatic sense; rather, they are harmonious elements within the larger composition. They underscore the human connection to the environment, suggesting a traditional way of life lived in close accord with the rhythms of nature. In works like "Fisherman's Hut" or scenes of peasants by a lake, the human element adds a layer of narrative and emotional depth without overwhelming the landscape itself. The mood is often one of peaceful coexistence, a gentle melancholy perhaps, but rarely one of overt hardship or social commentary in the vein of Jean-François Millet, though a shared respect for the peasant class is evident.

Mészöly's portrayal of rural life contributed to a broader European artistic interest in peasant themes during the 19th century. However, his approach was distinctly Hungarian, rooted in his personal observation and affection for the people and places he painted. He avoided grand gestures or overt storytelling, preferring to capture the quiet, everyday moments that defined the lives of his subjects.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Several paintings stand out in Geza Mészöly's oeuvre, encapsulating his artistic vision and technical skill.

"Fisherman's Hut" (Halászkunyhó), painted around 1874, is arguably his most iconic work. This painting depicts a simple thatched hut on the reedy shore of a lake, likely Balaton, under a soft, luminous sky. A small boat is pulled up nearby, and the overall atmosphere is one of profound tranquility and solitude. The subtle play of light on the water and the delicate rendering of the reeds showcase Mészöly's mastery of atmospheric effects. The painting's significance was further cemented when it was chosen to feature on the reverse of the Hungarian 1 million milpengő banknote issued in 1946, a testament to its enduring place in the national consciousness.

"Lido" (1877) represents a fascinating, though somewhat atypical, work in his output. Painted during his honeymoon in Venice, it displays a brighter palette and a more overtly Impressionistic handling of light and brushwork than his typical Hungarian scenes. The shimmering water, the fleeting effects of sunlight, and the lively atmosphere of the Venetian lagoon are captured with a freshness that suggests an engagement with the more avant-garde currents of European painting. While he did not fully embrace Impressionism, "Lido" demonstrates his awareness of and ability to work within its principles when the subject and environment called for it.

"Hay Wagon on the Puszta" (Szekér a pusztán), also known as "Carriage on the Grass," is another significant piece, likely from the early 1870s. It depicts a horse-drawn wagon traversing the vast Hungarian plain under a wide, expressive sky. The work captures the sense of space and the characteristic features of the Puszta, with the figures and wagon providing a focal point within the expansive landscape.

Other notable works include "Lake Balaton with Figures," "Pasture" (Legelő), "The Tisza Ferry," "Sand Mine" (Homokbánya), and "Iron Gate" (Vaskapu). Each of these paintings reinforces his commitment to depicting the Hungarian landscape with sensitivity and a keen eye for its unique character. His scenes often feature a low horizon line, giving prominence to the sky, which he rendered with great skill, capturing its myriad moods from serene calm to impending storm.

Mészöly in the Context of European Art

Geza Mészöly's art, while deeply rooted in Hungary, resonates with broader European artistic trends of the 19th century. His affinity with the French Barbizon School is paramount. Like Corot, Daubigny, and Rousseau, Mészöly valued direct observation of nature, plein-air sketching (though many larger works were finished in the studio), and the pursuit of capturing a specific mood or "impression" of a landscape. Corot's silvery tones and poetic sensibility find a clear echo in Mészöly's hazy, atmospheric scenes. Daubigny's river landscapes, often painted from his studio boat, also share common ground with Mészöly's depictions of the Tisza.

While not an Impressionist in the French sense – he did not adopt their scientific interest in color theory or their broken brushwork consistently – Mészöly shared their concern for light and atmosphere. His work can be seen as a form of lyrical Realism or poetic Naturalism, akin to that practiced by some members of the Hague School in the Netherlands, such as Anton Mauve or Jozef Israëls, who also depicted rural life and landscapes with a similar blend of realism and atmospheric sensitivity.

His training in Munich under artists like Albert Zimmermann connected him to the German landscape tradition, which itself had roots in Romanticism and an evolving Realism. The emphasis on capturing the "truth" of nature, albeit often an idealized or heroic truth in Zimmermann's case, provided a foundation that Mészöly adapted to his more intimate and lyrical vision. He can be seen as part of a generation of Central European artists who sought to reconcile academic training with the new impulses towards realism and plein-air painting emanating from France.

Hungarian Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Within Hungary, Geza Mészöly was part of a vibrant artistic scene. He was a contemporary of several other important Hungarian painters who were also shaping the course of the nation's art.

Mihály Munkácsy (1844–1900) was perhaps the most internationally famous Hungarian artist of the era. While Munkácsy also painted landscapes, he was best known for his dramatic genre scenes and large-scale historical and biblical paintings. Munkácsy's realism was often more robust and dramatic than Mészöly's, his figures more monumental, and his narratives more explicit. However, both artists shared a commitment to depicting Hungarian life and themes, albeit with different stylistic emphases.

László Paál (1846–1879) was another key contemporary landscape painter, and one whose artistic concerns closely mirrored Mészöly's. Paál spent much of his tragically short career in France, where he was deeply influenced by the Barbizon School. His forest interiors and moody landscapes share Mészöly's sensitivity to atmosphere and light, though Paál's work often possesses a more intense, sometimes melancholic, romanticism. Both artists were pivotal in introducing Barbizon principles into Hungarian art.

László Mednyánszky (1852–1919), though slightly younger, also became a leading figure in Hungarian landscape painting. Mednyánszky's work, often characterized by its mystical and pantheistic qualities, explored themes of transience and the sublime in nature. While his style evolved significantly throughout his career, his early landscapes share some common ground with Mészöly's atmospheric approach.

Pál Szinyei Merse (1845–1920) was a groundbreaking figure who pioneered plein-air painting and a form of Hungarian Impressionism. His famous work "Picnic in May" (1873) was radical for its time in its bold use of color and light. While Mészöly's style was generally more subdued, both he and Szinyei Merse were part of the broader movement towards modernism in Hungarian art, emphasizing direct observation and the depiction of contemporary life and landscape.

Other notable Hungarian artists of the period include historical painters like Bertalan Székely and Viktor Madarász, and Károly Lotz, known for his allegorical murals and portraits. While their primary genres differed from Mészöly's, they all contributed to the rich artistic tapestry of 19th-century Hungary. Later figures like Károly Ferenczy, a leading member of the Nagybánya artists' colony, would build upon the foundations laid by Mészöly and others in developing a distinctly Hungarian modern art. Sándor Bihari and Árpád Feszty also contributed to the diverse artistic expressions of the era.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Geza Mészöly passed away relatively young, on November 12, 1887, in his birthplace of Sárbogárd, at the age of 43. Despite his comparatively short career, he left an indelible mark on Hungarian art. His primary contribution lies in his sensitive and poetic interpretation of the Hungarian landscape, which he elevated to a subject of national importance. He successfully fused academic training with the emerging plein-air sensibilities of the Barbizon School, creating a style that was both technically accomplished and emotionally resonant.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of Hungarian landscape painters who continued to explore the beauty and unique character of their homeland. He helped to popularize a more intimate and atmospheric approach to landscape painting, moving away from the heroic or overly picturesque conventions of earlier periods. His focus on specific regions like Lake Balaton and the Tisza River helped to establish these locations as iconic subjects in Hungarian art.

The enduring appeal of Mészöly's work lies in its quiet beauty, its subtle emotional depth, and its authentic connection to the Hungarian land and its people. His paintings evoke a sense of nostalgia for a simpler, more harmonious way of life, and a deep appreciation for the transient beauty of the natural world. The continued display of his works in major Hungarian galleries, such as the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest, and their recognition, as exemplified by the banknote featuring "Fisherman's Hut," attest to his lasting significance. He remains a beloved figure, a painter who captured the soul of the Hungarian landscape with a gentle and lyrical touch.

Conclusion

Geza Mészöly was more than just a skilled painter of landscapes; he was a visual poet of the Hungarian countryside. His ability to capture the subtle nuances of light and atmosphere, combined with his empathetic portrayal of rural life, resulted in a body of work that is both timeless and deeply rooted in its national context. By embracing the principles of plein-air painting and the spirit of the Barbizon School, while adapting them to the specific character of his homeland, Mészöly played a crucial role in the development of modern Hungarian art. His legacy is one of quiet beauty, profound sensitivity, and an unwavering dedication to capturing the essence of Hungary on canvas, ensuring his place as one of the nation's most cherished artists.