Paul Désiré Trouillebert stands as a fascinating figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. Born in the bustling heart of Paris in 1829 and passing away there in 1900, his life spanned a period of immense artistic transformation. Primarily celebrated as a painter, Trouillebert navigated the realms of portraiture, the nude, and, most significantly, landscape painting. His artistic identity is deeply intertwined with the Barbizon School, a movement that championed realism and painting directly from nature, and he remains particularly noted for his stylistic kinship with the great Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Trouillebert's career reflects the shifting tastes and artistic debates of his time, positioning him as both a inheritor of tradition and a participant in the move towards modern sensibilities in art.

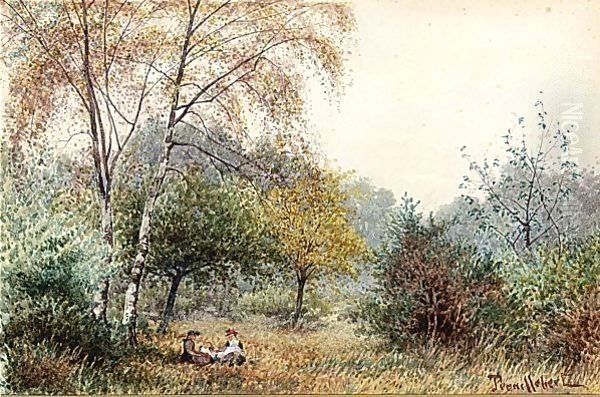

Trouillebert's journey as an artist involved mastering various genres, but it was his evocative landscapes that ultimately secured his reputation. He possessed a distinct ability to capture the subtle moods of the French countryside, particularly the tranquil beauty of its rivers and waterways. His canvases often glow with a soft, atmospheric light, rendered in a palette favouring gentle blues, silvery greys, and muted greens. This approach created scenes imbued with a quiet poetry and a profound sense of peace, resonating with the Barbizon ideal of finding harmony and truth in the natural world. His work found favour not only within France but also internationally, entering prestigious collections and ensuring his name endured beyond his lifetime.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Paul Désiré Trouillebert's artistic path began in Paris, the epicentre of the European art world in the 19th century. His formal training took place at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the cornerstone of academic art education in France. There, he studied under the tutelage of two notable masters: Antoine Auguste Ernest Hébert (often cited simply as Ernest Hébert) and Charles-François Jalabert. These instructors provided him with a solid foundation in the technical skills demanded by the academic tradition.

Ernest Hébert was a versatile artist, respected for his elegant portraits, historical and mythological scenes, and evocative depictions of Italian peasant life and landscapes, often tinged with a melancholic romanticism. His emphasis on refined drawing and subtle emotional expression likely influenced Trouillebert's early work in portraiture and genre scenes. Hébert himself had been a student of the Neoclassical painter Paul Delaroche, linking Trouillebert indirectly to an earlier generation of established artists.

Charles-François Jalabert, another student of Delaroche, was known for his polished academic style, often applied to religious subjects and sophisticated portraits. His instruction would have reinforced the importance of precise draughtsmanship, balanced composition, and a smooth, finished surface – hallmarks of the official art favoured by the Salon. Studying under both Hébert and Jalabert exposed Trouillebert to different facets of the academic system, providing him with the skills necessary to compete within the established art structures of the day, particularly the all-important Paris Salon. This formal training formed the bedrock upon which he would later build his more personal landscape style.

The Embrace of Barbizon and the Shadow of Corot

While Trouillebert's initial training was rooted in academic principles, his artistic spirit found its true resonance with the Barbizon School. This influential group of painters, active roughly from the 1830s to the 1870s, rejected the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism and the dramatic narratives of Romanticism. Instead, they sought a more direct, truthful engagement with nature, often working en plein air (outdoors) in the Forest of Fontainebleau near the village of Barbizon. Key figures like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña pioneered this approach.

Trouillebert became closely associated with this movement, absorbing its core tenets. His landscapes reflect the Barbizon emphasis on capturing the specific character of a place, the effects of light and atmosphere, and the quiet dignity of rural life and scenery. He shared their commitment to observing nature firsthand, translating its nuances onto canvas with sensitivity and skill. His favoured subjects – riverbanks, wooded interiors, tranquil ponds – align perfectly with the Barbizon repertoire.

Within the Barbizon sphere, one figure exerted a particularly profound influence on Trouillebert: Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. Corot, though often associated with Barbizon, maintained a unique style characterized by its poetic lyricism, soft focus, feathery brushwork, and masterful handling of silvery light. Trouillebert deeply admired Corot's work, and this admiration manifested clearly in his own landscapes. The similarities in their choice of subject matter, their palettes often dominated by subtle greys, greens, and blues, and their ability to evoke a specific, often misty or dawn-like, atmosphere are undeniable.

This stylistic proximity to Corot became a defining feature of Trouillebert's career, bringing both recognition and complication. His skill in capturing a Corot-like sensibility was remarkable, leading viewers and critics to frequently compare the two artists. While this association highlighted Trouillebert's talent, it also sometimes overshadowed his own distinct artistic voice, creating a complex legacy where his name would forever be linked, for better or worse, to that of the older master. Other Barbizon painters, like Constant Troyon known for his animal paintings within landscapes, or Jules Dupré with his more dramatic, heavily impastoed scenes, show the variety within the school, further contextualizing Trouillebert's specific affinity for Corot's gentler vision.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Techniques

Paul Trouillebert's artistic output demonstrates a versatility that extended beyond his celebrated landscapes. His early career saw him engage seriously with portraiture and genre painting, likely influenced by his academic training under Hébert and Jalabert. His portraits, such as the Mademoiselle A exhibited at his Salon debut in 1865, or La Servante (The Servant Girl) shown in 1874, likely displayed the technical proficiency expected by the Salon juries, focusing on accurate likeness and character portrayal within established compositional norms.

However, it was his transition to landscape painting in the 1860s that marked the defining shift in his career. Trouillebert developed a distinctive landscape style deeply rooted in the Barbizon tradition yet infused with his own sensibility. He excelled at depicting the serene waterways of France, frequently painting scenes along the banks of the Oise, Vienne, and Loire rivers. These works are characterized by their tranquil mood, often capturing the soft light of early morning or late afternoon. His palette, as noted, leaned towards cool, harmonious tones – silvery greys, muted greens, soft blues – which contributed to the overall poetic and atmospheric quality of his work.

Trouillebert's technique involved careful observation of nature, likely including plein air sketching, combined with studio refinement. His brushwork could vary, sometimes displaying the feathery touch reminiscent of Corot, at other times employing a slightly more defined approach. He paid close attention to the rendering of light and reflection on water, a recurring motif in his oeuvre. The interplay of light filtering through foliage and shimmering on the river's surface became one of his signature effects, lending his paintings a sense of immediacy and naturalism.

Intriguingly, Trouillebert also explored other themes. He produced a number of nudes, often set in landscape settings, such as The Bathers. These works sometimes incorporated elements of Orientalism, a popular trend in 19th-century French art fascinated with depictions of the Middle East and North Africa, although Trouillebert's interpretations were generally more subdued compared to the dramatic visions of artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme or Eugène Delacroix. This thematic diversity showcases an artist willing to explore different genres while maintaining a consistent painterly quality across his work.

Key Works and Salon Recognition

Trouillebert's career was significantly anchored by his participation in the Paris Salon, the official, juried exhibition that was the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage in 19th-century France. He made his debut in 1865 and continued to exhibit regularly for nearly two decades, until 1884. This consistent presence indicates his ambition and his acceptance within the mainstream art establishment, even as his style aligned with the more progressive Barbizon group.

Several works stand out as representative of his achievements. Au Bois Rossignollet (In the Rossignollet Woods), exhibited at the Salon of 1869, is often cited as a key landscape painting that garnered significant positive attention. This work likely exemplified his mature landscape style, showcasing his ability to capture the dense, yet light-filled atmosphere of a woodland interior, a theme favoured by Barbizon painters like Théodore Rousseau. The positive reception of such works helped solidify his reputation as a skilled landscape artist.

Another notable work is La corvée d’eau (Fetching Water or Water Duty). While specific exhibition details might vary, paintings with this theme, often depicting figures by a riverbank engaged in daily tasks, were characteristic of his output. These works combined his skill in landscape with elements of genre painting, portraying a harmonious vision of rural life. The emphasis would typically be on the atmospheric setting, the play of light on water, and the integration of the figures within the natural environment, rendered in his signature cool palette.

His painting Lion d'Or et lac Léman à Saint-Gingolph, Suisse (Lion d'Or Hotel and Lake Geneva at Saint-Gingolph, Switzerland) demonstrates his application of the Barbizon aesthetic to locations beyond the immediate Fontainebleau area. This work, later documented in his studio sale catalogue of 1894, captures a specific view with the characteristic attention to light and atmosphere associated with his style. Similarly, depictions of famous landmarks, such as El castillo de Chenonceaux (The Château de Chenonceaux), show him applying his landscape techniques to architectural subjects integrated within their natural surroundings.

His portrait La Servante, exhibited in 1874, reminds us of his continued engagement with figure painting alongside his landscape work. The regular exhibition of both landscapes and figurative works at the prestigious Salon underscores Trouillebert's competence across different genres and his sustained effort to build a successful artistic career within the competitive Parisian art world. His works were not only exhibited but also collected, eventually finding their way into major museum collections across the globe.

The Corot Controversy: Imitation or Affinity?

The close stylistic relationship between Paul Trouillebert and Camille Corot led to one of the most discussed aspects of Trouillebert's career: the frequent comparison and occasional confusion between their works. This similarity reached a point of public controversy, most notably in an incident involving the renowned French writer Alexandre Dumas fils (son of the author of The Three Musketeers).

In 1883, Dumas fils purchased a landscape painting attributed to Corot. Subsequently, it was revealed or alleged that the painting was actually the work of Trouillebert. This led to a legal case or significant public dispute. The incident highlighted the challenges of attribution in the art market, particularly when one artist worked closely in the style of another, more famous figure. It also inevitably cast a shadow on Trouillebert's reputation, raising questions about whether the similarity was merely stylistic affinity or, in some instances, perhaps intentional imitation aimed at capitalizing on Corot's fame and market value.

It's crucial to approach this issue with nuance. The 19th-century art market was rife with copies, pastiches, and outright forgeries. Corot himself was one of the most imitated artists of his time, partly due to his generosity in encouraging younger painters and sometimes even signing students' work. Trouillebert's mastery of a Corot-like style was undeniable, and it's plausible that some dealers or collectors intentionally or unintentionally misattributed his works to the more sought-after Corot.

There is no definitive evidence to suggest Trouillebert systematically engaged in fraudulent activity himself. He signed his own works, and his consistent participation in the Salon under his own name indicates an artist building his own career. However, the Dumas fils affair cemented the perception of Trouillebert as a highly skilled "follower" or even "imitator" of Corot. While this acknowledged his technical prowess, it also potentially limited the appreciation of his own unique contributions and artistic merits. The controversy underscores the complex interplay between artistic influence, market forces, and reputation in the art world. It remains a significant anecdote in Trouillebert's biography, illustrating the powerful, and sometimes problematic, legacy of his connection to Corot.

Trouillebert and His Contemporaries

Paul Trouillebert operated within a vibrant and dynamic artistic milieu in 19th-century Paris. His connections extended beyond his teachers and his primary influence, Corot, placing him in dialogue with various artistic currents of the time. His association with the Barbizon School naturally brought him into contact or shared exhibition spaces with its leading figures. Besides Corot, Rousseau, Millet, and Daubigny, he would have been aware of the work of Diaz de la Peña, known for his richly coloured forest scenes and mythological figures, and Jules Dupré, whose landscapes often possessed a more dramatic, turbulent quality compared to Trouillebert's prevailing serenity.

The Paris Salon was the main arena where Trouillebert encountered the broader spectrum of contemporary art. Here, his landscapes, rooted in Barbizon realism, were exhibited alongside works representing vastly different styles. He would have seen the highly finished, often sentimental or historical paintings of academic giants like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Alexandre Cabanel, who enjoyed immense official success. Their polished surfaces and idealized subjects stood in stark contrast to the Barbizon emphasis on observed nature and textured brushwork.

He also witnessed the rise of Realism, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet. Courbet's unvarnished depictions of rural life and his politically charged canvases challenged academic conventions in a more confrontational way than the gentler naturalism of Barbizon. While Trouillebert's work shared Realism's focus on contemporary subjects and observation, it lacked Courbet's overt social commentary and rugged execution.

Furthermore, Trouillebert's career overlapped with the emergence of Impressionism. Artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Alfred Sisley, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who began exhibiting independently in the 1870s, pushed the principles of plein air painting further than the Barbizon generation. They focused on capturing the fleeting effects of light and colour with broken brushwork and a brighter palette, dissolving form in a way that Trouillebert generally did not. While Trouillebert's atmospheric landscapes, particularly his river scenes, can be seen as precursors to Impressionism in their sensitivity to light and reflection, his style remained more grounded in the tonal harmonies and structured compositions associated with Corot and the Barbizon tradition. He represented a bridge, upholding the values of mid-century landscape painting while the next generation forged a more radical path.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

In the later decades of his life, Paul Trouillebert continued to paint, maintaining his focus on the landscapes that had become his specialty. He remained active, producing views of the French countryside, particularly river scenes, characterized by the soft light and tranquil atmosphere that were his hallmarks. While the rise of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism shifted the avant-garde focus, Trouillebert's work continued to find appreciation among collectors who favoured the established Barbizon aesthetic and its poetic interpretation of nature.

His participation in the Paris Salon appears to have ceased after 1884, but this does not necessarily mean he stopped painting or exhibiting elsewhere. Studio sales, like the one documented in 1894, indicate he remained an active professional artist. He passed away in Paris in 1900, leaving behind a substantial body of work encompassing landscapes, portraits, and nudes.

Trouillebert's legacy is somewhat complex, largely due to the persistent comparisons with Corot. For many years, he was primarily seen as a talented follower rather than an innovator. However, contemporary art historical perspectives tend to offer a more balanced view. While acknowledging the profound influence of Corot, scholars and curators now also recognize Trouillebert's individual skill in capturing light and atmosphere, his consistent quality, and his contribution to the Barbizon tradition. His paintings are appreciated for their intrinsic beauty, their technical competence, and their evocative portrayal of the French landscape.

His works are held in numerous public collections around the world, testifying to his enduring appeal and historical significance. Prestigious institutions such as the Musée d'Orsay in Paris (inheriting works from the Louvre's collection), the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and the National Museum of Western Art in Tokyo, among others, include paintings by Trouillebert. This presence in major museums ensures that his art continues to be seen, studied, and appreciated, securing his place as a significant, if sometimes underestimated, figure in 19th-century French painting.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Nature

Paul Désiré Trouillebert navigated the rich and often turbulent currents of 19th-century French art with considerable skill and dedication. From his academic training under Hébert and Jalabert to his deep immersion in the ethos of the Barbizon School, he forged a path that, while profoundly influenced by Camille Corot, ultimately bore his own distinct signature. His primary contribution lies in his landscape painting, where he masterfully captured the serene beauty and subtle atmospheres of the French countryside, particularly its rivers and forests.

His work embodies the Barbizon pursuit of naturalism and truth in representation, rendered with a poetic sensibility that resonates with viewers even today. The characteristic silvery light, the harmonious cool palettes, and the tranquil moods of his canvases offer a calming, contemplative vision of nature. While the shadow of Corot and the controversies surrounding attribution shaped his historical reception, a closer look reveals an artist of genuine talent and consistent quality.

Trouillebert stands as an important link between the mid-century realism of Barbizon and the later developments in French landscape painting. His dedication to observing and interpreting the natural world, his technical proficiency across multiple genres, and the enduring appeal of his evocative scenes secure his position as a noteworthy artist of his era. His paintings, found in museums worldwide, continue to offer a window onto the landscapes of 19th-century France, seen through the eyes of a sensitive and skilled painter.