Giovanni Battista Cima, known more commonly by his geographical appellation "da Conegliano" (from Conegliano), stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the rich tapestry of Venetian Renaissance art. Active during a period of profound artistic transformation, from the late Quattrocento into the early Cinquecento, Cima carved a distinct niche for himself. His oeuvre is characterized by a gentle, lyrical piety, a mastery of serene landscapes, and a consistent dedication to religious themes, primarily altarpieces and devotional images of the Madonna and Child. While he operated in the shadow of giants like Giovanni Bellini, and his career overlapped with the burgeoning talents of Giorgione and Titian, Cima's contribution to the Venetian school is undeniable, offering a body of work that exudes tranquility, refined craftsmanship, and a deeply felt spirituality.

Origins and Early Career: The Road from Conegliano to Venice

The precise birth year of Giovanni Battista Cima remains a subject of minor scholarly debate, though it is generally accepted to be either 1459 or 1460. He was born in Conegliano, a town in the Veneto region, then part of the mainland territories of the powerful Republic of Venice, now within the province of Treviso. His father, Pietro, was a cloth-shearer, or cimator di panni. It is from this paternal profession that the family name "Cima" (meaning "top" or "shearer," in this context likely referring to the finishing of cloth) is believed to have originated. This humble, artisanal background provides a common narrative thread for many Renaissance artists who rose through skill and patronage.

Little is definitively known about Cima's earliest artistic training. Records indicate his presence as a painter in Vicenza in 1489, where he completed his first documented altarpiece, the Virgin and Child Enthroned with Saints James and Jerome, for the church of San Bartolomeo. This early work already hints at the clarity and compositional balance that would become hallmarks of his style. It is highly probable that during his time in Vicenza, or perhaps even earlier, he came under the influence of Bartolomeo Montagna, a prominent painter active in Vicenza whose style was characterized by a certain sculptural solidity and a somewhat austere gravity, derived in part from the influence of Andrea Mantegna and Antonello da Messina. Montagna's impact can be discerned in the somewhat firm modeling of Cima's early figures.

By 1492, Cima had established himself in Venice, the vibrant artistic and commercial heart of the region. This move was crucial for his development, placing him directly within the orbit of the leading workshops and artistic currents of the time. Venice, with its unique light, its rich tradition of color, and its wealthy patrons (both ecclesiastical and private), offered unparalleled opportunities for an ambitious painter. He would reside and work primarily in Venice for the remainder of his career, though he maintained connections with his hometown, returning to Conegliano for a period in 1516 before his death.

The Development of a Lyrical Style: Influences and Characteristics

Upon arriving in Venice, Cima da Conegliano inevitably encountered the pervasive influence of Giovanni Bellini, the undisputed doyen of the Venetian school at the time. Bellini's workshop was a crucible of talent, and his innovations in the use of oil paint, his mastery of atmospheric light, and his ability to imbue religious scenes with profound human emotion set the standard for Venetian painting. Cima absorbed these lessons deeply, and many scholars consider him one of Bellini's most accomplished, if stylistically distinct, followers or spiritual successors.

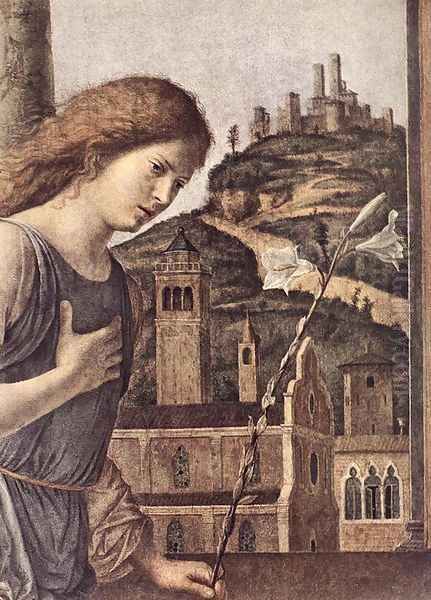

Cima's style, however, was not merely imitative. He developed a personal idiom characterized by a serene and gentle piety. His Madonnas are often depicted with a sweet, contemplative grace, their expressions tender and approachable. The Christ Child, too, is rendered with a naturalism that avoids overt sentimentality. These figures are typically set against meticulously rendered landscapes that play a crucial role in establishing the mood of his paintings. These landscapes, often featuring distant blue mountains reminiscent of his native Conegliano foothills, rolling hills, and carefully observed botanical details, are bathed in a clear, even light that contributes to the overall sense of tranquility. This emphasis on landscape was a growing trend in Venetian art, seen in the works of Bellini, Carpaccio, and later, Giorgione, but Cima's particular fusion of devotional figures with idyllic, almost pastoral backgrounds became one of his signatures.

His palette is noteworthy for its clarity and harmony. Cima often employed rich, warm colors for the draperies of his figures – deep reds, blues, and golds – which stand out against the cooler tones of his landscapes. He demonstrated a fine understanding of light and shadow, using subtle gradations to model forms and create a sense of volume, though he generally avoided the dramatic chiaroscuro that would characterize the work of later artists like Tintoretto or Caravaggio. His light is typically diffused and gentle, contributing to the peaceful atmosphere of his compositions.

While primarily a painter of religious subjects, Cima also demonstrated a keen eye for detail in rendering textures – the sheen of silk, the richness of velvet, the intricacies of architectural ornamentation. This attention to detail, combined with his compositional clarity and harmonious color, lent his works an air of refined elegance. Some art historians have noted a certain conservatism in Cima's style; he largely remained faithful to the Quattrocento ideals of balance and clarity, even as younger artists like Giorgione and Titian began to explore more dynamic compositions and a more sensuous handling of paint. This, however, should not be seen as a limitation but rather as a testament to his consistent artistic vision. He was sometimes referred to as the "Masaccio of Venice," an intriguing comparison suggesting a shared clarity of form and directness, though Cima's temperament was far gentler than the revolutionary Florentine.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

Cima da Conegliano's oeuvre is dominated by altarpieces and smaller devotional paintings, with the Madonna and Child, often accompanied by saints (a format known as a Sacra Conversazione), being a recurrent theme.

One of his most celebrated early altarpieces is the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Peter, Romuald, Benedict, and Paul, painted around 1495-1497 for the church of San Michele in Isola, Venice (now in the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin). This work showcases his developing mastery: the serene Virgin, the carefully individualized saints, and the expansive landscape visible behind the architectural throne. The clarity of the composition and the harmonious integration of figures and setting are characteristic.

The Baptism of Christ, executed around 1492-1494 for the high altar of the church of San Giovanni in Bragora, Venice, where it still resides, is another pivotal work. Here, Cima's ability to render a sacred event with both solemnity and a sense of naturalism is evident. The figures of Christ and John the Baptist are central, flanked by angels, with the River Jordan meandering through a luminous landscape that recedes into the distance. The depiction of light on the water and the delicate rendering of the foliage demonstrate his keen observational skills. This work is often compared to Giovanni Bellini's own treatments of the subject, highlighting both Cima's debt to the master and his own emerging voice.

His Madonna and Child paintings are numerous and consistently popular. A fine example is The Virgin and Child (c. 1496-1499, National Gallery, London), where the Virgin tenderly supports the standing Christ Child, both figures set against a backdrop of a tranquil landscape with a distant town. The intimacy and gentle emotion of such works made them highly sought after for private devotion. Another version, The Virgin and Child (c. 1499-1502), is housed in the Museo Civico in Vicenza, showing the enduring connection to his earlier place of work.

The Madonna Enthroned with Saints (c. 1505), now in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, is a mature example of his Sacra Conversazione format. The Virgin and Child are centrally enthroned, surrounded by saints including John the Baptist, Mary Magdalene, and others, each rendered with distinct character. The architectural setting is grand, yet opens onto a typically serene Cima landscape. The rich colors and meticulous detail are exemplary of his mature style.

The Incredulity of Saint Thomas with Saint Magnus (c. 1504-1505), originally for the Scuola dei Mureri (stonemasons' guild) in Venice and now in the Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice, is a powerful narrative work. It depicts the moment Thomas touches Christ's wound, conveying the emotional intensity of the scene with a restrained dignity. The figures are solid and well-modeled, and the composition is carefully balanced. This work, along with others, demonstrates Cima's ability to handle more complex multi-figure compositions effectively.

Another significant altarpiece is the Assumption of the Virgin (c. 1500-1502), though its current location and specific details can vary in attribution discussions, it highlights his engagement with grander theological themes. His treatment of such subjects always maintained a sense of order and divine grace.

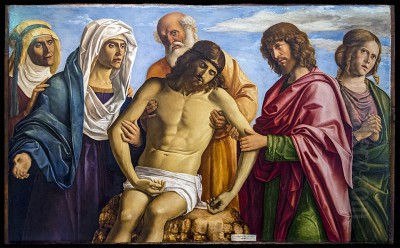

The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (c. 1504), housed in the Galleria Estense, Modena, shows Cima's capacity for conveying profound grief. The figures of the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and Saint John mourn over the body of Christ, set against a dramatic, rocky landscape that amplifies the sorrowful mood. Even in such a tragic scene, Cima avoids excessive melodrama, opting instead for a deeply felt pathos.

His works for his native Conegliano also hold importance, such as the altarpiece for the Duomo (Cathedral) of Conegliano, depicting Saints Peter, John the Baptist, Catherine of Alexandria, and Prosdocimus with Angels (1493). This commission underscores his continued ties to his birthplace even after establishing himself in Venice.

Cima within the Venetian Artistic Milieu: Contemporaries and Context

Cima da Conegliano operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment. His primary point of reference was undoubtedly Giovanni Bellini, whose influence shaped a generation of painters. Cima can be seen as one of the most faithful, yet individual, interpreters of the Bellinesque tradition, particularly in his emphasis on landscape, serene mood, and luminous color. While Bellini's later works moved towards a greater softness and atmospheric fusion, Cima often retained a slightly crisper definition of form, a characteristic that perhaps links back to his earlier contact with Montagna or the broader influence of Paduan art, exemplified by Andrea Mantegna, Bellini's brother-in-law, whose emphasis on line and classical form had a profound impact on Northern Italian art.

He was a contemporary of Vittore Carpaccio, another prominent Venetian painter known for his large narrative cycles, such as the Legend of Saint Ursula. While Carpaccio's focus was often on detailed storytelling and depictions of Venetian life, both artists shared a clarity of style and a love for meticulously rendered settings.

The Vivarini family, particularly Alvise Vivarini, represented another significant workshop tradition in Venice, sometimes seen as rivals to the Bellini. Alvise's style, also influenced by Antonello da Messina (who had a transformative, albeit brief, impact on Venetian painting with his mastery of the oil medium and Netherlandish realism), was characterized by a certain sharpness and intensity, contrasting with Cima's gentler approach.

As Cima's career progressed into the early 16th century, he witnessed the rise of a new generation of Venetian masters who would redefine the school: Giorgione and the young Titian. Giorgione, though his career was tragically short, introduced a new poetic and enigmatic quality to Venetian painting, with a softer, more atmospheric handling of paint (sfumato) and a focus on mood and landscape that often overshadowed narrative clarity. Titian, initially influenced by both Bellini and Giorgione, would go on to become the dominant figure of the Venetian High Renaissance, known for his dynamic compositions, rich color, and dramatic power.

Compared to these emerging giants, Cima's style might appear more conservative, rooted in the Quattrocento. He did not fully embrace the sfumato of Giorgione or the dynamic energy of Titian. Instead, he continued to refine his own vision of serene piety and harmonious landscapes. This consistency, however, ensured a steady stream of commissions from patrons who appreciated his particular blend of traditional devotion and refined aesthetics. Other painters active in Venice or the Veneto during this period, such as Lorenzo Lotto (known for his psychological acuity and sometimes eccentric compositions) or Palma Vecchio (celebrated for his sensuous depictions of female figures and pastoral scenes), further illustrate the diversity of artistic expression in the region. Even earlier figures like Carlo Crivelli, though working mostly in the Marches, came from the Venetian tradition and his highly decorative and linear style offers another point of contrast.

Later Career, Workshop, and Enduring Legacy

Cima da Conegliano maintained a productive workshop in Venice, fulfilling commissions for churches and private patrons throughout the Veneto and beyond. The consistency of his style suggests a well-organized studio practice. While specific pupils are not always easy to identify with certainty, his influence can be seen in the work of lesser-known painters active in the Venetian mainland.

In 1516, Cima returned to his native Conegliano. The reasons for this move are not entirely clear; perhaps it was a desire to spend his final years in his hometown, or it may have been related to specific commissions. He continued to be active as a painter during this period. Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano died in Conegliano, likely in 1517 or 1518. Tax records and other documents help pinpoint this timeframe.

For a period, particularly in the 19th century, Cima's reputation was somewhat overshadowed by the more famous names of the Venetian High Renaissance like Titian, Veronese, and Tintoretto, and even by the enigmatic allure of Giorgione. However, modern art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized his distinct contribution. His works are prized for their gentle beauty, their technical refinement, and their sincere devotional quality. He is seen as a crucial figure who, while deeply indebted to Giovanni Bellini, forged a personal style that perfectly captured a particular strain of Venetian piety – calm, contemplative, and deeply connected to the beauty of the natural world.

Scholarly Perspectives and Unresolved Questions

While much is known about Cima's career and output, some areas remain open to scholarly discussion. The exact nature and extent of his early training, particularly his relationship with Bartolomeo Montagna, continue to be debated. The precise chronology of some of his undated works can also be a subject of discussion, often relying on stylistic analysis.

The interpretation of specific iconographies or the identification of all the saints in his complex altarpieces can sometimes present challenges, requiring deep knowledge of local cults and hagiography. The question of workshop participation in some of his later or larger commissions is also a standard area of art historical inquiry for prolific Renaissance masters.

The very name "Cima" being derived from his father's profession as a cimator is widely accepted, but the nuances of such occupational surnames and their adoption are part of broader socio-historical studies. The reasons for his relatively late return to Conegliano also invite speculation, though concrete evidence is scarce.

Despite these minor areas of ongoing research, Cima's artistic identity is remarkably coherent. His consistent style and thematic concerns make his works readily identifiable. The "unresolved mysteries" surrounding Cima are less about dramatic lacunae in his biography and more about the finer points of connoisseurship and contextual understanding that enrich the study of any Old Master.

Cima's Works in Collections Today

Today, works by Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano can be found in many of the world's leading museums, as well as in churches in Venice and the Veneto.

Key Italian collections include:

Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice: Holding several important altarpieces, including The Incredulity of St. Thomas and Madonna of the Orange Tree.

Churches in Venice: Such as San Giovanni in Bragora (Baptism of Christ).

Duomo of Conegliano: Still housing his 1493 altarpiece.

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan: Possesses significant works like Saints Peter Martyr, Nicholas of Bari, Benedict and an Angel Musician.

Uffizi Gallery, Florence: Home to the Madonna Enthroned with Saints.

Galleria Estense, Modena: Houses The Lamentation.

Museo Civico, Vicenza: Contains The Virgin and Child (c. 1499-1502).

Parma, Galleria Nazionale: Holds works attributed to Cima.

Internationally, his paintings are well-represented:

National Gallery, London: Features several key pieces, including The Virgin and Child (c. 1496-99) and The Incredulity of St Thomas.

Gemäldegalerie, Berlin: Owns the Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints Peter, Romuald, Benedict, and Paul.

Louvre Museum, Paris: Has examples of his Madonnas.

National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.: Collections include Madonna and Child with Saint Jerome and Saint John the Baptist.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Holds works by Cima.

Walters Art Museum, Baltimore: Has examples of his devotional panels.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna: Also among the collections with his works.

Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg: Features paintings by Cima.

This widespread distribution attests to his historical importance and the enduring appeal of his art.

Conclusion: The Enduring Appeal of a Gentle Master

Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano was a painter of remarkable consistency and refined sensibility. He successfully navigated the dynamic artistic landscape of late 15th and early 16th century Venice, creating a body of work that, while perhaps not as revolutionary as some of his contemporaries, possesses a timeless appeal. His serene Madonnas, his harmonious compositions, and his luminous landscapes continue to resonate with viewers, offering moments of calm contemplation and spiritual solace. As a key figure in the Bellinesque tradition, Cima played an important role in disseminating and personalizing the core tenets of Venetian Renaissance painting, leaving behind a legacy of gentle beauty and sincere piety that secures his place in the annals of art history. His art serves as a testament to the enduring power of quiet devotion and meticulous craftsmanship in an era of grand artistic ambitions.