Carlo Crivelli stands as one of the most distinctive and fascinating painters of the Italian Renaissance. Active primarily in the Marche region of Italy, his work is a unique amalgamation of late Gothic decorative richness and emerging Renaissance naturalism. Born in Venice around 1430 or 1435, Crivelli's artistic journey took him away from the mainstream artistic currents of Florence and Rome, allowing him to cultivate a highly personal and instantly recognizable style. His paintings, characterized by sharp linearity, vibrant colors, elaborate ornamentation, and an almost obsessive attention to detail, offer a window into a singular artistic vision that, though somewhat overlooked in his own time, has captivated art historians and enthusiasts since its rediscovery in the 19th century.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Venice and Padua

Carlo Crivelli was born into a family of painters in Venice, a city renowned for its opulent art and vibrant cultural exchange. His father was identified as Jacopo Crivelli, also a painter, though little is known about his work. This familial background undoubtedly provided Carlo with an initial exposure to the craft. While direct documentation of his earliest training is scarce, art historians generally agree on the formative influences that shaped his distinctive style.

A key figure in Crivelli's early development was likely Francesco Squarcione, a painter and teacher based in Padua. Squarcione's workshop was a significant artistic hub, attracting numerous young talents. He was known for his passion for classical antiquity, amassing a collection of Roman sculptures and artifacts that his pupils studied. This emphasis on classical forms, albeit often interpreted through a somewhat rigid and linear lens, left an indelible mark on many artists who passed through his studio. Among Crivelli's contemporaries in Squarcione's circle were prominent figures like Andrea Mantegna, Cosimo Tura, Marco Zoppo, and Giorgio Schiavone (also known as Juraj Ćulinović). The influence of Mantegna, in particular, with his sculptural figures, sharp outlines, and mastery of perspective, can be discerned in Crivelli's work, though Crivelli would ultimately forge a path less concerned with pure classical humanism and more inclined towards expressive intensity and decorative splendor.

Beyond Squarcione, the artistic environment of Venice itself played a crucial role. The Vivarini family workshop, led by Antonio Vivarini and later his brother Bartolomeo Vivarini and son Alvise Vivarini, was a dominant force in Venetian painting during the mid-15th century. Their style, characterized by bright colors, intricate details, and a lingering Gothic sensibility, shares certain affinities with Crivelli's later output. It is also plausible that Crivelli had contact with the workshop of Jacopo Bellini, father of the more famous Gentile and Giovanni Bellini. Jacopo's sketchbooks, filled with studies of perspective, classical motifs, and naturalistic details, were influential resources for many Venetian artists. The emphasis on rich surfaces, patterned textiles, and gilded elements, so prevalent in Venetian art, clearly resonated with Crivelli's own artistic inclinations.

A Venetian Scandal and Relocation to the Marche

Crivelli's career in Venice was cut short by a personal scandal. In 1457, he was sentenced to six months in prison and fined for adultery, having "abducted and carnally known" Tarsia, the wife of a sailor named Francesco Cortese. This incident seems to have made his continued presence in Venice untenable. Following his release, Crivelli left his native city, never to return. His first documented stop was Zara (now Zadar) in Dalmatia, then under Venetian rule, where he is recorded as a resident and citizen. He spent several years there, and some early works are attributed to this period.

By 1468, Crivelli had moved to the Marche region on the Adriatic coast of central Italy. This region, relatively isolated from the major artistic centers of Florence and Rome, became his adopted home for the remainder of his life. He settled primarily in Ascoli Piceno but also worked extensively in other towns like Fermo, Camerino, and Matelica. The Marche provided a fertile ground for Crivelli's art. The local patrons, often religious confraternities and provincial nobility, appreciated his meticulous craftsmanship and the traditional, yet vibrant, religious imagery he produced. This environment allowed Crivelli to develop his unique style without the pressure to conform to the rapidly evolving trends of High Renaissance art.

His departure from Venice, while forced by circumstance, ultimately contributed to the singularity of his artistic voice. In the Marche, he was a leading master, able to refine his distinctive blend of Gothic decorative traditions and Renaissance observational acuity, largely independent of the stylistic shifts occurring elsewhere in Italy. This relative isolation helped preserve the somewhat archaic, yet intensely personal, qualities of his art.

Artistic Style and Techniques: A Fusion of Traditions

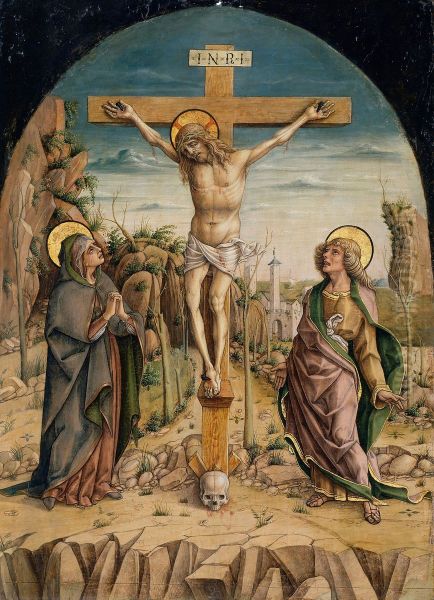

Carlo Crivelli's art is immediately recognizable for its unique synthesis of late Gothic elegance and early Renaissance precision. He worked primarily in tempera on panel, a medium that lends itself to sharp lines and brilliant, jewel-like colors. His figures are often characterized by a certain wiry tension, with expressive, sometimes gaunt, faces and elongated hands. While he demonstrated an understanding of perspective, his spatial constructions often serve more as a stage for intricate detail and symbolic elements than as a pursuit of pure Albertian illusionism.

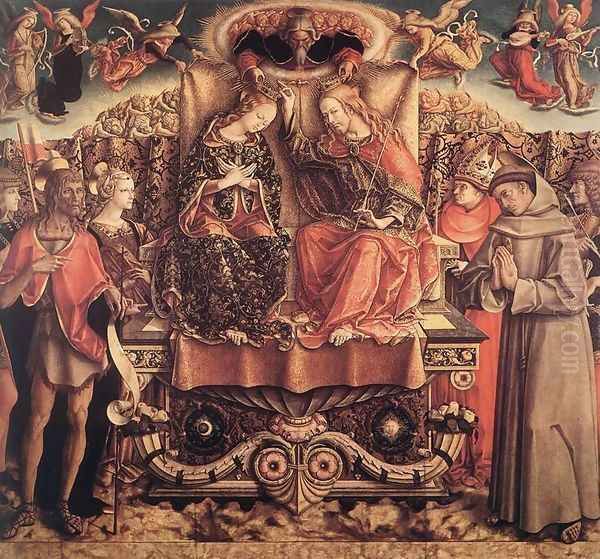

One of the most striking features of Crivelli's work is his lavish use of ornamentation. Gold backgrounds, a hallmark of earlier Gothic painting, persist in many of his altarpieces, lending them an otherworldly, iconic quality. He was a master of pastiglia, a technique involving the application of raised gesso, often gilded or painted, to create three-dimensional details like halos, crowns, armor, and architectural embellishments. This adds a tangible, almost sculptural, richness to the surface of his paintings.

Crivelli also delighted in trompe-l'oeil effects. He frequently included meticulously rendered fruits, flowers, and even insects in his compositions. Swags of apples, pears, and cucumbers, often rendered with astonishing realism, hang in his painted spaces or rest on fictive ledges. These elements are not merely decorative; they are imbued with complex Christian symbolism. For example, apples often allude to the Original Sin, while cucumbers could symbolize redemption or resurrection. A fly, meticulously painted as if resting on the picture surface, might signify the transience of life or the presence of evil.

His approach to human emotion is intense and often dramatic. The grief in his Pietàs is palpable, conveyed through contorted features and anguished gestures. Even in more serene subjects like the Madonna and Child, there is an underlying current of heightened sensibility. His figures, while not always conforming to classical ideals of beauty, possess a powerful psychological presence. This expressive quality, combined with his meticulous detail and decorative richness, sets him apart from many of his contemporaries, such as the more serene and harmoniously balanced compositions of Giovanni Bellini or Perugino.

Major Themes and Representative Works

The vast majority of Crivelli's surviving works are religious in theme, primarily altarpieces (polyptychs and single panels), Madonnas, and depictions of saints. His patrons were largely ecclesiastical institutions and private individuals seeking devotional images.

The Annunciation with Saint Emidius (1486): Perhaps Crivelli's most famous work, now in the National Gallery, London, this painting is a dazzling display of his mature style. Commissioned for the Church of the Santissima Annunziata in Ascoli Piceno, it commemorates the granting of local autonomy to the city by Pope Sixtus IV. The painting is a riot of architectural detail, perspectival complexity, and symbolic minutiae. The Virgin Mary is depicted in an opulent domestic interior, receiving the divine message from the Archangel Gabriel. A ray of golden light, carrying the Holy Spirit as a dove, pierces the wall of her house. Saint Emidius, the patron saint of Ascoli, kneels beside Gabriel, presenting a model of the city. The painting is filled with trompe-l'oeil elements, including a precisely rendered cucumber and apple in the foreground, and a peacock, symbolizing immortality, perched on a balcony. The inscription "LIBERTAS ECCLESIASTICA" celebrates the city's newly acquired freedom.

Madonna and Child Compositions: Crivelli produced numerous variations on the theme of the Madonna and Child, each imbued with his characteristic style. The Madonna and Child in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan (often called the "Brera Madonna" by Crivelli, not to be confused with Piero della Francesca's work of the same common name), shows the Virgin enthroned, holding the Christ Child, surrounded by meticulously rendered fruits and a rich brocade backdrop. The Ancona Madonna (Pinacoteca Civica Francesco Podesti, Ancona) is another notable example, showcasing his ability to combine regal solemnity with tender intimacy. The fruits and flowers in these paintings are never incidental; they carry layers of theological meaning related to Christ's sacrifice, Mary's purity, and the promise of salvation.

Pietàs and Lamentations: Crivelli's depictions of the dead Christ supported by angels or mourned by the Virgin and saints are among his most emotionally powerful works. The Lamentation over the Dead Christ (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Rome) and The Dead Christ Supported by Two Angels (National Gallery, London) exemplify his capacity for conveying profound grief through angular forms, expressive faces, and a focus on the wounds of Christ. These works often feature a stark, almost unsettling realism in the depiction of Christ's suffering, combined with the decorative splendor of gilded backgrounds and elaborate halos.

Polyptychs: Many of Crivelli's major commissions were for large, multi-paneled altarpieces, or polyptychs. The Polyptych of San Domenico from Camerino (now dispersed, with panels in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, and elsewhere) and the Polyptych of Porto San Giorgio (also dispersed) are prime examples. These complex structures allowed Crivelli to depict a range of saints and narrative scenes, each panel a miniature masterpiece of detail and color. The central panel typically featured the Madonna and Child or a significant saint, flanked by other saints, with smaller predella panels below illustrating scenes from their lives or the life of Christ.

Saint George and the Dragon (c. 1470): Housed in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston (though a version is also attributed to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), this work showcases Crivelli's ability to handle dynamic narrative subjects. The chivalric theme of the knight vanquishing evil is rendered with characteristic energy and attention to the ornate details of armor and costume. The dramatic intensity of the scene is heightened by the almost calligraphic rendering of the dragon and the landscape.

Mary Magdalene (c. 1476): Often depicted as a sumptuously dressed, elegant figure, Crivelli's portrayals of Mary Magdalene (e.g., Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam) emphasize her traditional attribute, the jar of ointment. Her rich attire and refined features are rendered with Crivelli's typical precision, highlighting her transformation from sinner to saint. These images combine sensuous beauty with spiritual devotion.

Other saints frequently depicted by Crivelli include Saint Jerome, often shown with his lion and cardinal's attire, Saint Peter with his keys, and Saint Sebastian, whose martyrdom offered artists an opportunity to depict the idealized male nude, though Crivelli's interpretations often retain a certain Gothic angularity.

Crivelli and His Contemporaries: A Singular Path

While Crivelli's early training connected him to the artistic currents of Padua and Venice, his long career in the Marche set him on a somewhat independent trajectory. His relationship with Francesco Squarcione and the Paduan circle, including Andrea Mantegna, Cosimo Tura, and Marco Zoppo, provided a foundation in linear precision and an interest in classical motifs. However, Crivelli's interpretation of these elements was always highly personal, leaning more towards decorative richness and expressive intensity than Mantegna's rigorous classicism or Tura's often unsettling, metallic forms.

In Venice, the dominant figures during Crivelli's formative years and later were the Vivarini family and, increasingly, the Bellini family. Giovanni Bellini, in particular, moved towards a softer, more atmospheric style, emphasizing color and light to create harmonious and emotionally resonant compositions. Crivelli's art, by contrast, remained committed to sharp outlines, brilliant, localized color, and a more overtly decorative aesthetic. While both artists achieved profound emotional depth, their means were different: Bellini through subtle gradations of tone and light, Crivelli through expressive linearity and symbolic detail.

Crivelli's brother, Vittorio Crivelli, was also a painter and seems to have followed Carlo to Dalmatia and later worked in the Marche. Vittorio's style is heavily indebted to Carlo's, but generally considered less inventive and refined. He often replicated his brother's compositions and motifs, contributing to the dissemination of the "Crivellesque" style in the region.

Compared to Central Italian masters like Piero della Francesca, known for his serene monumentality and mathematical perspective, or Perugino, with his sweet-faced Madonnas and harmonious Umbrian landscapes, Crivelli's art appears more idiosyncratic and rooted in an earlier, Gothic sensibility. He did not fully embrace the High Renaissance ideals of idealized naturalism and classical harmony that came to dominate Italian art in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Instead, he perfected a unique visual language that, while incorporating Renaissance elements like anatomical observation and perspectival awareness, remained deeply personal and infused with a late medieval spirit. Other artists like Gentile da Fabriano, active earlier in the Marche, also showcased a love for intricate detail and courtly elegance, suggesting a regional taste that Crivelli might have tapped into.

Later Career, Recognition, and Knighthood

Carlo Crivelli remained highly productive throughout his career in the Marche, receiving numerous commissions and maintaining a successful workshop. His distinctive style found favor with local patrons, and he seems to have enjoyed considerable esteem. A significant mark of recognition came in 1490 when Ferdinand II of Naples conferred a knighthood upon him. Thereafter, Crivelli often added the title "Miles" (Knight) to his signature, as seen in works like the Madonna della Candeletta (Pinacoteca di Brera). This honor suggests that his reputation extended beyond the immediate confines of the Marche.

Despite this recognition, Crivelli's art remained somewhat outside the mainstream of Italian Renaissance development. His geographical isolation from major artistic centers like Florence, Rome, and even Venice (after his departure) meant that he was less directly influenced by the rapid stylistic innovations occurring in those cities. This allowed him to cultivate his unique style, but it also meant that his work did not have the widespread impact of artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, or Michelangelo.

Carlo Crivelli is believed to have died in Ascoli Piceno around 1495. His artistic legacy in the Marche was continued to some extent by his brother Vittorio and other local painters who imitated his style, but his highly individual manner did not lend itself to a broad school of followers.

Legacy and Rediscovery: An Enduring Fascination

After his death, Carlo Crivelli's fame gradually faded. His style, with its emphasis on intricate detail, gold backgrounds, and somewhat archaic forms, fell out of fashion as the High Renaissance and later Mannerist and Baroque aesthetics came to dominate. For centuries, he remained a relatively obscure figure in the grand narrative of Italian art.

It was not until the 19th century that Crivelli's work began to be rediscovered and appreciated anew. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England, with their admiration for the art of the "primitives" (artists before Raphael), found a kindred spirit in Crivelli's meticulous detail, brilliant color, and sincere religious feeling. Critics like John Ruskin also championed early Italian painters, contributing to a reassessment of artists who had been overlooked by earlier generations focused on the High Renaissance. Figures like Edward Burne-Jones, a prominent second-generation Pre-Raphaelite, were particularly drawn to the decorative qualities and intense emotionalism of artists like Crivelli and Mantegna.

Museums and private collectors began to acquire Crivelli's works, and art historians started to study his oeuvre in greater depth. His paintings, once dismissed as merely eccentric or old-fashioned, came to be valued for their unique beauty, technical brilliance, and profound spiritual intensity. The very qualities that had made him seem out of step with the High Renaissance – his sharp linearity, his love of ornament, his blend of realism and stylization – were now seen as strengths, evidence of a singular artistic vision.

Modern scholarship continues to explore the complexities of Crivelli's art, examining his iconography, his relationship to his patrons, and his place within the broader context of 15th-century Italian painting. His works are now prized possessions in major museums around the world, and exhibitions dedicated to his art attract considerable public and critical attention.

Conclusion: A Master of Singular Vision

Carlo Crivelli remains a captivating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the history of art. His journey from Venice to the relative seclusion of the Marche allowed him to cultivate a style that was deeply personal, blending the decorative traditions of International Gothic with the observational acuity of the early Renaissance. His paintings, with their jewel-like colors, meticulous details, elaborate ornamentation, and intense emotional expression, stand apart from the work of many of his contemporaries.

While he may not have shaped the overarching trajectory of Renaissance art in the way that figures like Masaccio, Donatello, or Leonardo da Vinci did, Crivelli perfected a unique and compelling visual language. His commitment to craftsmanship, his mastery of complex symbolism, and his ability to imbue traditional religious themes with a vibrant, almost startling, immediacy ensure his enduring appeal. The rediscovery of his work in the 19th century rightfully restored him to a prominent place among the masters of the Italian Quattrocento, a testament to the timeless power of his singular artistic vision. His art continues to fascinate, offering a glimpse into a world where spiritual devotion, meticulous observation, and decorative splendor coexist in breathtaking harmony.