Introduction: The Artist and His Time

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo stands as a pivotal figure in the rich tapestry of Italian Baroque art, celebrated particularly for his mastery of still life painting. Active primarily in Naples during the latter half of the 17th century, Ruoppolo carved a distinct niche for himself within the vibrant Neapolitan school. Born in Naples in 1629 and passing away in the same city in 1693, his life spanned a period of intense artistic activity and cultural exchange. He specialized in the genre known as natura morta (still life, literally "dead nature"), bringing an unparalleled vibrancy and realism to depictions of fruits, flowers, and other inanimate objects, securing his place as one of the genre's most accomplished practitioners in Italy.

Naples, during Ruoppolo's lifetime, was a bustling metropolis under Spanish rule, a major European capital, and a crucible of artistic innovation. The legacy of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, who had worked in the city earlier in the century, cast a long shadow, profoundly influencing local artists with his dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) and his intense naturalism. It was within this dynamic environment, where artistic patronage flourished and diverse influences converged, that Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo developed his unique artistic voice, contributing significantly to the golden age of Neapolitan painting.

The Neapolitan Context and the Ruoppolo Legacy

The 17th century witnessed the flourishing of still life painting across Europe, and Naples became a particularly fertile ground for this genre. Neapolitan still life distinguished itself through its often opulent arrangements, dramatic lighting inherited from Caravaggism, and a palpable sense of realism that sometimes bordered on the tactile. Artists explored the textures, colours, and forms of local produce, fish, flowers, and everyday objects, often imbuing their compositions with symbolic meaning, reflecting themes of abundance, transience, or the bounty of nature.

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo was not an isolated figure but emerged from an artistic milieu where still life was gaining prominence. He belonged to an artistic family, the Ruoppolos, who played a significant role in the development of this genre in Naples. His nephew, Giuseppe Ruoppolo (c. 1630/1639 – c. 1710), also became a renowned still-life painter, initially training under Giovanni Battista and continuing the family's artistic tradition. The Ruoppolo name became synonymous with high-quality Neapolitan still life, characterized by technical brilliance and a deep connection to the natural world observed in the region.

The artistic environment in Naples was competitive yet collaborative. Painters often worked for the same patrons, responded to similar artistic trends, and sometimes even collaborated on specific projects. Figures like Luca Forte, considered one of the pioneers of Neapolitan still life, and Paolo Porpora, known for his intricate depictions of flowers and undergrowth often including reptiles and insects, were contemporaries who contributed to the city's reputation as a center for the genre. This shared context provided both inspiration and competition for Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo.

Artistic Style: Naturalism, Light, and Baroque Sensibility

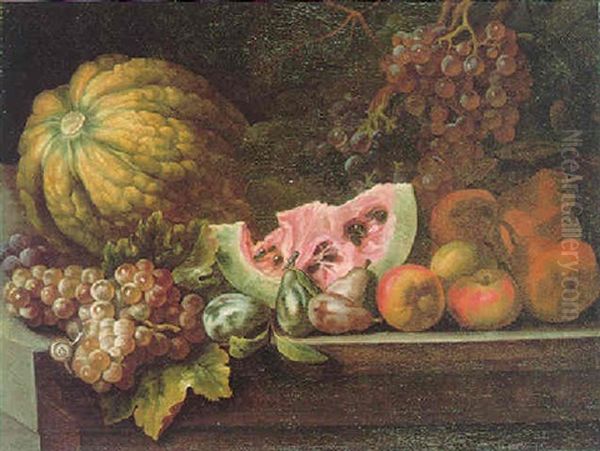

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo's style is fundamentally rooted in naturalism, a commitment to depicting the world as accurately and convincingly as possible. His paintings are celebrated for their meticulous attention to detail, capturing the varied textures of fruit skins – the smooth sheen of grapes, the rough peel of citrus, the velvety surface of peaches, or the distinct pattern of a watermelon rind. He rendered the play of light across these surfaces with remarkable skill, creating a sense of volume and presence that makes the objects seem almost tangible.

The influence of Caravaggio is evident in Ruoppolo's dramatic use of chiaroscuro. Light often falls intensely upon the central subjects, which emerge vividly from dark, undefined backgrounds. This technique not only enhances the realism and three-dimensionality of the objects but also imbues the compositions with a sense of Baroque drama and dynamism. Unlike the starker, more psychologically intense drama of Caravaggio's religious or genre scenes, Ruoppolo's use of light serves primarily to heighten the sensuous appeal and visual richness of the natural forms he depicted.

While influenced by Caravaggio and the broader trends of Roman Baroque painting, particularly the works of still-life specialists like Michelangelo Pace del Campidoglio, Ruoppolo maintained a distinct Neapolitan character in his art. His compositions are often abundant, overflowing with produce, reflecting the fertility of the Campanian region. There is a certain vibrancy and optimism in his work, a celebration of nature's bounty rendered with technical virtuosity. His colour palette is typically rich and warm, further enhancing the lushness of his subjects.

Themes and Subjects: Celebrating Nature's Bounty

Ruoppolo's primary subjects were fruits and vegetables, often arranged in elaborate, cascading compositions. Grapes, figs, pomegranates, melons, citrus fruits, apples, pears, and gourds feature prominently, frequently depicted spilling out of baskets or arranged directly on stone ledges or tables. He had a particular fondness for depicting watermelons, often shown sliced open to reveal their vibrant red flesh and dark seeds, a motif that became something of a signature element in his work and that of his followers.

Flowers also appear in his oeuvre, sometimes integrated with fruit arrangements, adding touches of delicate colour and form. Less commonly, he might include elements like fish or shells, reflecting the maritime environment of Naples, although his fame rests predominantly on his fruit and vegetable pieces. Occasionally, small creatures like insects or birds might be subtly incorporated, adding a touch of life and perhaps hinting at themes of natural cycles or the transient nature of beauty (vanitas), though his work generally emphasizes abundance over decay.

The arrangements themselves are often complex and dynamic, moving beyond simple tabletop displays. Fruits might tumble downwards, pile up in generous heaps, or be dramatically lit against shadowy backdrops. This compositional energy aligns with the broader aesthetics of the Baroque era, which favoured movement, drama, and emotional intensity. Ruoppolo's still lifes, while focused on inanimate objects, possess a remarkable vitality and visual energy. They served not only as realistic depictions but also as luxurious decorative pieces, appreciated for their beauty and technical skill.

Representative Works and Collections

While specific titles were not always consistently recorded in the 17th century, several works exemplify Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo's style and are attributed to him with confidence. Generic titles often describe the content accurately:

Still Life with Fruit: Numerous paintings fall under this description, typically showcasing a lavish assortment of seasonal fruits. A notable example, sometimes dated to the 1680s, might feature grapes, figs, peaches, and pomegranates rendered with characteristic detail and dramatic lighting. These works highlight his ability to differentiate textures and capture the ripeness of the fruit.

Still Life with Fruit and Watermelon: Paintings featuring his signature sliced watermelon are among his most recognizable. An example possibly dating around 1688 demonstrates his skill in depicting the juicy interior of the melon alongside other fruits, creating a focal point of vibrant colour and texture.

Still Life with Fruit and Vegetables: These compositions broaden the range of subjects, incorporating items like pumpkins, gourds, or artichokes alongside fruits. They showcase his versatility in rendering diverse forms and surfaces, often creating rich tapestries of natural bounty.

Still Life with Grapes: Ruoppolo excelled at painting grapes, capturing the translucent quality of the skins, the powdery bloom, and the way light reflects off the individual berries. Works focusing on grapes often display a particularly refined technique.

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo's paintings were highly sought after during his lifetime and continue to be prized today. His works can be found in major international museums and prestigious private collections. Notable institutions holding his paintings include the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the Museo di Capodimonte and the Museo Nazionale di San Martino in Naples, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, among others. The presence of his work in these collections attests to his enduring importance in the history of European art.

Contemporaries, Patrons, and Artistic Exchange

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo operated within a network of artists, patrons, and dealers that shaped the Neapolitan art scene. His most significant artistic relationship was arguably with his nephew, Giuseppe Ruoppolo, who trained in his workshop. Giuseppe absorbed his uncle's style but developed his own variations, often favouring slightly cooler palettes or different compositional structures, yet the foundational influence remained clear. Giuseppe's painting Shells is sometimes interpreted as containing a depiction related to his apprenticeship under Giovanni Battista, expressing respect for his master.

Interaction with other leading Neapolitan painters was inevitable. Luca Forte and Paolo Porpora were key figures in the earlier development and establishment of Neapolitan still life. While direct collaboration records between Giovanni Battista and these specific artists are scarce, they shared the same artistic environment and likely responded to similar market demands and stylistic influences. Porpora, who also spent time in Rome, may have acted as a conduit, facilitating connections between Neapolitan artists like Ruoppolo and the Roman art world, potentially including artists like Michelangelo Cerquozzi, known for his bambocciate (genre scenes) and still lifes.

A documented instance of collaboration involved Luca Giordano, one of Naples' most famous and prolific Baroque painters, known for his large-scale frescoes and altarpieces but also involved in various artistic projects. In the 1680s, during preparations for the Corpus Domini festival in Rome, Giordano oversaw aspects of the artistic decorations. Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo was among the artists commissioned to contribute natura morta paintings for this event, indicating a professional relationship and mutual recognition between these major figures.

The Dutch painter Abraham van Beyeren, known for his lavish banquet still lifes, spent time in Naples, and while direct contact with Giovanni Battista isn't confirmed, van Beyeren is known to have collaborated with Giuseppe Ruoppolo. This connection highlights the international dimension of the Neapolitan art scene and the cross-currents of influence between Italian and Northern European still life traditions. Another prominent contemporary, though working primarily in landscape and battle scenes, was Salvator Rosa, whose dramatic style also contributed to the overall character of Neapolitan Baroque art.

Patronage was crucial. The Vandeneyden family, wealthy Flemish merchants based in Naples, were significant collectors and patrons of Neapolitan art. Records show they commissioned and purchased works from Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo, as well as from Luca Forte and Luca Giordano. A transaction from 1673 notes a still life by Ruoppolo selling for the substantial sum of 60 ducats, indicating the high value placed on his work. These patrons, along with others like the influential collector Gaspar Roomer, played a vital role in supporting artists and shaping artistic tastes in the city, facilitating the exchange of artworks between Naples, Rome, and Flanders.

Anecdotes, Market Value, and Reputation

Beyond formal records, glimpses of Ruoppolo's life and reputation emerge. The aforementioned 1673 sale price of 60 ducats for a still life demonstrates that his works commanded prices comparable to those of other genres, like landscape painting, challenging the traditional hierarchy that often placed still life lower than historical or religious subjects. This reflects the high esteem in which sophisticated collectors held masterful natura morta.

His works were often acquired for decorative purposes, sometimes designed as overdoors (sovrapporte) or integrated into larger interior schemes in palaces and villas. This function underscores the aesthetic appeal and luxurious quality of his paintings, which could enhance the opulence of domestic settings. The description of his art, possibly originating from contemporaries or early critics, as representing a "truth more beautiful than nature itself," speaks to the idealization inherent in his realism – an ability to capture nature's essence while elevating it through artistic skill and composition.

His influence extended beyond his direct pupils. The sheer quality and popularity of his work set a standard for still life painting in Naples. Artists like Giuseppe Recco, another major figure in Neapolitan still life specializing often in fish and kitchen scenes, worked concurrently and contributed to the genre's prominence, likely aware of and responding to Ruoppolo's achievements. The Ruoppolo workshop, led by Giovanni Battista and later continued in spirit by Giuseppe, became a benchmark for excellence in the field.

Today, Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo's paintings continue to be highly valued on the art market. Major works appearing at auction can fetch significant sums, ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of euros or dollars, depending on size, quality, condition, and provenance. This enduring market appeal reflects the sustained appreciation for his technical brilliance, the inherent beauty of his subjects, and his important place within the history of Baroque art.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo's primary contribution lies in his consolidation and elevation of the Neapolitan still life tradition. Building on the foundations laid by earlier artists and absorbing the powerful influence of Caravaggism, he developed a distinctive style characterized by robust naturalism, dramatic lighting, rich colour, and dynamic composition. He became arguably the leading specialist in fruit and vegetable still life in Naples during the second half of the 17th century.

His influence was direct and significant, most notably through his nephew and pupil, Giuseppe Ruoppolo, ensuring the continuation of his stylistic approach into the early 18th century. More broadly, his work contributed to the high reputation of the Neapolitan school of still life painting across Italy and Europe. His ability to blend meticulous realism with Baroque decorative sensibilities made his work appealing to a wide range of patrons and collectors.

In the grand narrative of art history, Ruoppolo is recognized as a master of the natura morta genre. He demonstrated that still life could be a vehicle for profound artistic expression, showcasing not only technical virtuosity but also a deep appreciation for the beauty and abundance of the natural world. His paintings are more than mere inventories of produce; they are carefully constructed works of art that engage the senses and celebrate the visual richness of everyday objects transformed by the artist's hand. He remains a key figure for understanding the development of Baroque painting in Naples and the evolution of still life as a major genre in European art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Nature

Giovanni Battista Ruoppolo remains a celebrated master of the Italian Baroque, a painter whose canvases burst with life despite their focus on "dead nature." His legacy is preserved in the stunningly realistic and vibrant depictions of fruits and vegetables that continue to captivate viewers in museums worldwide. As a central figure in the Neapolitan school, he absorbed the dramatic naturalism of Caravaggio and the richness of the Baroque aesthetic, forging a powerful and influential style. Through his meticulous technique, his dynamic compositions, and his evident delight in the textures and colours of the natural world, Ruoppolo not only documented the bounty of his region but also created enduring works of art that stand as testaments to the beauty that can be found in the everyday. His contribution solidified Naples's position as a major center for still life painting and secured his own place as one of the genre's most accomplished exponents.