Introduction: Bridging North and South

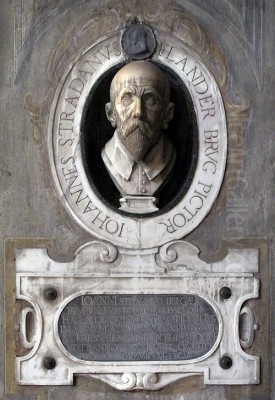

Giovanni Stradano, known also by his Flemish name Jan van der Straet and the Latinized Johannes Stradanus, stands as a fascinating and pivotal figure in the art history of the late Renaissance. Born in Bruges in 1523 and passing away in his adopted city of Florence in 1605, Stradano's long and remarkably productive career bridged the artistic traditions of Northern Europe with the prevailing styles of Mannerist Italy. He was a versatile master, excelling not only in painting frescoes and altarpieces but also as a prolific designer of tapestries and prints, activities that cemented his reputation both within the Florentine court and across the European continent. His work, deeply embedded in the cultural and political life of Medicean Florence, offers a rich tapestry of historical events, mythological narratives, religious devotion, and even early explorations of science and global discovery.

Stradano's unique artistic identity was forged through his Flemish training, emphasizing meticulous detail and realism, which he skillfully integrated with the elegance, dynamism, and intellectual sophistication characteristic of Italian Mannerism, particularly as practiced in Florence under the influence of masters like Giorgio Vasari. Working for decades under the patronage of the powerful Medici dukes, Stradano contributed significantly to the lavish decoration of their palaces and villas, leaving behind a legacy of works that continue to captivate viewers with their intricate compositions, narrative richness, and technical brilliance. His influence extended far beyond Florence, thanks largely to the numerous engravings made after his designs, which circulated widely and inspired artists from Antwerp to the Americas.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Flanders

Giovanni Stradano's artistic journey began in Bruges, a city that, while past its absolute zenith, remained a significant artistic center in Flanders during the early 16th century. Born into a family with artistic connections, he received his initial training locally, likely absorbing the lingering influence of the Early Netherlandish masters known for their precision, luminous color, and detailed observation of the natural world. This foundational training would instill in him a lifelong appreciation for meticulous rendering and textural accuracy, traits that would distinguish his work even after decades in Italy.

Seeking broader opportunities and more advanced instruction, Stradano moved to Antwerp, by then the bustling economic and artistic hub of the Low Countries. There, he entered the workshop of Pieter Aertsen, a prominent painter known for his innovative market and kitchen scenes that often incorporated religious narratives in the background. This apprenticeship, starting around the mid-1540s, was crucial. Aertsen's bold compositions, earthy realism, and interest in genre subjects likely broadened Stradano's artistic horizons. In 1545, Stradano achieved a significant professional milestone by being accepted as a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke, the city's powerful artists' guild, signifying his competence and readiness to practice independently.

However, like many ambitious Northern artists of his generation, Stradano felt the pull of Italy, the heartland of the Renaissance and classical antiquity. Drawn by the prospect of studying ancient Roman art firsthand and immersing himself in the works of Italian masters like Michelangelo and Raphael, he embarked on the southward journey around 1550, a decision that would irrevocably shape his career and artistic style. This move was part of a larger pattern of cultural exchange between Northern and Southern Europe, enriching both traditions.

Arrival in Italy and Establishment in Florence

Stradano's journey southward likely included stops in other artistic centers, such as Lyon and Venice, before he ultimately arrived in Florence around 1550. Florence, though arguably past the peak of its High Renaissance glory, remained a vibrant artistic center, particularly under the ambitious cultural program of Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. The city was dominated by the artistic movement known as Mannerism, characterized by stylized elegance, complex allegories, elongated figures, and often artificial grace, a style exemplified by artists like Bronzino and Pontormo.

Upon arriving in Florence, Stradano quickly sought opportunities to integrate himself into the local artistic scene. His Flemish training, particularly his skill in detailed rendering, may have been seen as both exotic and valuable. A pivotal moment came when he connected with Giorgio Vasari, the painter, architect, and art historian who was then the dominant figure in Florentine art, largely due to his role as Duke Cosimo I's chief artistic organizer and propagandist.

Stradano joined Vasari's large and busy workshop, a collective of artists engaged in major decorative projects for the Medici. This association proved immensely beneficial, providing Stradano with stable employment, high-profile commissions, and the chance to work alongside other talented artists. He rapidly became one of Vasari's most trusted and capable assistants, valued for his skill, reliability, and perhaps his unique Northern perspective. His integration into the Florentine artistic milieu was swift, and he would remain based in the city for the rest of his long life, becoming a respected member of the artistic community. He also made brief working trips to other Italian cities, including Rome and Naples, further broadening his experience of Italian art.

The Medici Court: Patronage and Projects

Giovanni Stradano's career became inextricably linked with the Medici dynasty, particularly Duke Cosimo I and his sons, Francesco I and Ferdinando I. For nearly half a century, he served as a court artist, contributing significantly to the visual culture that projected Medici power, sophistication, and dynastic legitimacy. This patronage provided him with unparalleled opportunities to work on large-scale, prestigious projects that defined the artistic landscape of late 16th-century Florence.

His contributions were diverse. He painted frescoes in the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of Florentine government and the Duke's residence. He designed elaborate tapestry cycles, a medium highly valued by rulers for its portability, costliness, and narrative potential. These tapestries often depicted hunting scenes, historical events, or allegories celebrating Medici virtues and achievements. For instance, he designed cartoons for the famous hunting series woven for the Medici villa at Poggio a Caiano, showcasing his skill in capturing animal movement and landscape detail.

Stradano also worked on decorations for Medici villas and participated in the ephemeral decorations for state events like weddings and triumphal entries, further cementing his role within the court's artistic apparatus. His ability to work across different media and adapt his style to various contexts made him an invaluable asset to his patrons. The subject matter often directly served Medici interests, depicting historical battles won by Florentine forces, allegories of good government, or scenes reflecting the Duke's personal interests, such as alchemy and natural history, particularly for Francesco I's famous Studiolo.

Collaboration with Giorgio Vasari: The Palazzo Vecchio

The collaboration between Giovanni Stradano and Giorgio Vasari was one of the most significant artistic partnerships in mid-16th-century Florence, particularly focused on the extensive redecoration of the Palazzo Vecchio. Vasari, entrusted by Duke Cosimo I with transforming the medieval palace into a magnificent ducal residence, relied heavily on a team of skilled artists, among whom Stradano quickly emerged as a key figure. From the early 1550s until Vasari's death in 1574, Stradano worked closely with him on numerous projects within the palace.

Stradano's contributions are evident in several major decorative cycles. He assisted Vasari in the Quartiere degli Elementi (Apartments of the Elements) and the Quartiere di Leone X (Apartments of Leo X), painting frescoes based on Vasari's overall designs but often executed with his own distinct touch, blending Flemish detail with Mannerist forms. His hand is clearly identifiable in specific scenes, where his Northern penchant for landscape and genre detail enriches Vasari's grand historical and allegorical narratives.

One notable area where Stradano worked extensively is the Sala di Gualdrada, where he painted lively scenes of Florentine life and festivals, including the famous depiction of a Calcio Fiorentino (Florentine football) match in Piazza Santa Maria Novella and a Bonfire Game in Piazza Santo Spirito. These works showcase his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions and capture the energy of contemporary events. He also painted the ceiling fresco Penelope at her Loom in the Quartiere di Penelope, demonstrating his engagement with classical mythology. His reliability and skill made him indispensable to Vasari's ambitious program, which aimed to visually articulate the history and glory of Florence and its Medici rulers.

Other Artistic Collaborations and Connections

Beyond his crucial relationship with Vasari, Stradano interacted and collaborated with numerous other artists active in Florence and beyond, reflecting the interconnected nature of the Renaissance art world. His early Italian years may have included a period working with Francesco Salviati, another prominent Mannerist painter known for his sophisticated and ornate style. Some scholars suggest Stradano refined his understanding of Italian figure drawing and complex composition under Salviati's influence, possibly collaborating on decorations at the Palazzo Sacchetti in Rome or other projects before Salviati's death in 1563.

Within Vasari's Palazzo Vecchio team, Stradano worked alongside other notable painters like Alessandro Allori (often considered Bronzino's main pupil and successor), Agnolo Bronzino himself (the premier Medici court portraitist), and possibly Francesco Ubertini, known as Bachiacca, who was also involved in Medici commissions, particularly tapestry design. This collaborative environment fostered an exchange of ideas and techniques, although the dominant style was largely dictated by Vasari's Mannerist vision.

Stradano's activities as a designer for prints brought him into collaboration with engravers, most notably Philips Galle in Antwerp. Galle and his workshop engraved hundreds of designs supplied by Stradano, covering diverse subjects from biblical scenes and saints' lives to allegories, hunting scenes, and the famous Nova Reperta (New Discoveries) series. This partnership was vital for disseminating Stradano's inventions across Europe. He also collaborated with the Florentine nobleman and writer Luigi Alamanni on the conceptualization and design of the Americae Retectio (Discovery of America) print series, highlighting the intellectual dimension of his work. His network thus extended from the workshops of Florence to the print publishing houses of Antwerp.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Traditions

Giovanni Stradano's artistic style is compelling precisely because it represents a unique synthesis of his Northern European origins and his adopted Italian environment. He retained a Flemish sensitivity to detail, texture, and the specificities of the natural world throughout his career. This is evident in his rendering of fabrics, armor, animals, and landscape backgrounds, which often possess a tactile quality and observational accuracy rooted in the tradition of Jan van Eyck and his successors.

However, Stradano fully embraced the prevailing Mannerist aesthetic of Florence. He adopted the elongated proportions, graceful S-curve poses (`figura serpentinata`), complex allegorical content, and sophisticated compositional structures favored by artists like Vasari and Bronzino. His figures often display elegant, sometimes artificial, postures and gestures. He learned the Italian emphasis on `disegno` – the intellectual and practical mastery of drawing and design – which underpinned Florentine artistic practice.

His color palette could range from the rich, jewel-like tones reminiscent of Flemish painting to the brighter, sometimes more acidic or shot-silk color harmonies characteristic of Mannerism. He excelled at creating dynamic, multi-figured compositions, skillfully organizing complex scenes whether on a large fresco wall or a small print design. This blend of Northern realism and Italianate elegance allowed him to tackle a wide range of subjects with versatility and flair, making his style recognizable yet adaptable to different commissions and media. He was less interested in the profound psychological depth of High Renaissance masters like Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael, focusing more on narrative clarity, decorative effect, and intellectual ingenuity.

Diverse Themes: History, Religion, Science, and Discovery

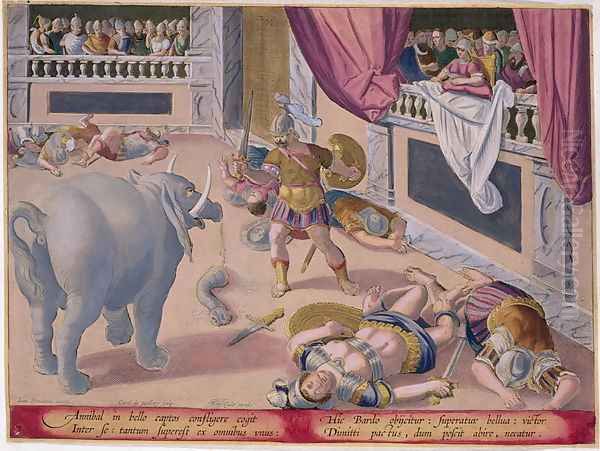

The thematic range of Giovanni Stradano's work is remarkably broad, reflecting both the demands of his patrons and his own intellectual curiosity. As a court artist, he was frequently commissioned to depict historical events, particularly those celebrating Medici military victories or diplomatic successes. These scenes, often destined for frescoes or tapestries in the Palazzo Vecchio, required careful research and dramatic composition to convey the intended political message, such as the frescoes depicting Florentine triumphs over Pisa and Siena.

Religious subjects formed a significant part of his output, including altarpieces for Florentine churches and numerous designs for prints illustrating biblical stories, lives of saints, and devotional themes. His illustrations for Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, particularly the Inferno, stand out for their imaginative power and dramatic intensity, visualizing the poet's terrifying descriptions of Hell with a focus on psychological impact. He joined a lineage of artists, including Sandro Botticelli, who sought to translate Dante's epic into visual form.

Stradano also engaged with mythological themes, often drawing from Ovid's Metamorphoses or other classical sources, as seen in the Penelope ceiling fresco. Furthermore, he displayed a keen interest in the burgeoning scientific and technological developments of his time. His famous painting, The Alchemist's Studio, created for Francesco I's Studiolo in the Palazzo Vecchio, provides a fascinating glimpse into the world of early chemical experimentation, reflecting the Duke's own passion for alchemy. This interest extended to his print designs, particularly the Nova Reperta series, which celebrated recent inventions like the printing press, gunpowder, and discoveries like the Americas. His depictions of the Discovery of America, often allegorical, captured the European fascination with the New World and Florence's perceived role in its exploration through figures like Amerigo Vespucci.

Exploring Key Works

Several key works exemplify Giovanni Stradano's style, versatility, and thematic concerns:

The Alchemist's Studio (c. 1570): Painted for the Studiolo of Francesco I in the Palazzo Vecchio, this small, detailed panel depicts a bustling workshop filled with furnaces, distillation apparatus, and artisans engaged in various tasks, likely related to glassmaking or chemical experiments. It reflects Francesco I's deep interest in science and the occult, and showcases Stradano's Flemish skill in rendering intricate details and textures within a complex interior scene.

Illustrations for Dante's Inferno (c. 1587): Stradano produced a series of powerful drawings illustrating Dante's Hell, later engraved by other artists. These works are noted for their dramatic compositions, grotesque figures, and imaginative visualization of the poem's punishments and landscapes. Unlike Botticelli's more linear and ethereal drawings, Stradano's interpretations often emphasize the physical horror and psychological torment described by Dante, using strong contrasts of light and shadow.

The Discovery of America Series (late 16th century): Designed by Stradano and engraved primarily by Philips Galle and his circle, this series, including the famous print America, depicted Amerigo Vespucci's encounter with a personification of the New World. Often allegorical and incorporating symbols of the continent's flora, fauna, and indigenous peoples (sometimes based on inaccurate stereotypes), these prints were immensely popular and influential in shaping European perceptions of the Americas. They highlight Stradano's role in translating contemporary events and exploration narratives into compelling visual form.

Frescoes in the Palazzo Vecchio (c. 1555-1572): Stradano's extensive work throughout the palace includes historical scenes, allegories, and genre depictions. Works like the View of San Giovanni Valdarno or the Siege of Piombino demonstrate his ability to handle large-scale historical narratives within Vasari's framework. The genre scenes in the Sala di Gualdrada, such as the Bonfire Game in Piazza Santo Spirito and the Calcio Fiorentino, are particularly valuable for their lively depiction of contemporary Florentine customs and social life.

Penelope at her Loom (Palazzo Vecchio): This ceiling fresco in the apartments named after Penelope showcases Stradano's engagement with classical mythology. It depicts Odysseus's faithful wife at her weaving, a symbol of domestic virtue and patience. The work demonstrates his ability to adapt his style to mythological subjects, employing the elegant forms and graceful compositions typical of Florentine Mannerism.

Master of Design: Prints and Tapestries

While a skilled painter, Giovanni Stradano's widest influence arguably came through his prolific work as a designer for prints and tapestries. In the 16th century, engravings and tapestries were crucial media for disseminating artistic ideas, narratives, and political messages across wide geographical areas. Stradano excelled in creating detailed preparatory drawings (`cartoons` for tapestries, `modelli` for prints) that could be effectively translated into these other media by specialized craftsmen.

He designed numerous tapestry cycles for the Medici, including the aforementioned hunting scenes for Poggio a Caiano and narrative series for the Palazzo Vecchio. These designs required a strong sense of composition suitable for large-scale weaving, clarity of narrative, and decorative richness. His tapestry cartoons were executed by the Arazzeria Medicea, the Medici tapestry workshop founded by Cosimo I, employing skilled weavers often recruited from Flanders.

His activity as a designer for prints was even more extensive and far-reaching. He supplied hundreds of drawings to engravers, primarily in Antwerp, the leading center for print production in Northern Europe. His collaboration with Philips Galle and his workshop resulted in popular series like the Nova Reperta, the Americae Retectio, numerous hunting scenes (Venationes Ferarum, Avium, Piscium), biblical illustrations, lives of saints (like the Acts of the Apostles), and allegorical compositions. These prints circulated widely throughout Europe and even reached the Spanish colonies in the Americas, influencing local artists and providing visual models for various subjects. Stradano's ability to create clear, engaging, and easily reproducible designs made him a key figure in the visual culture of the late Renaissance.

Influence and Lasting Legacy

Giovanni Stradano's impact on the art world extended both during his lifetime and after his death in 1605. As a prominent member of Vasari's team and a long-serving Medici court artist, he played a significant role in shaping the visual environment of late Mannerist Florence. His ability to seamlessly blend Flemish detail with Italianate elegance provided a model for other artists navigating the cultural exchange between North and South.

His most significant legacy, however, lies in the widespread dissemination of his designs through prints. Engraved by masters like Philips Galle, Adriaen Collaert, and the Wierix brothers, Stradano's compositions reached a vast audience. These prints served as source material for artists across Europe and the New World. For example, elements from his hunting scenes and religious narratives can be found echoed in paintings, decorative arts, and even book illustrations produced far from Florence. His depictions in the Nova Reperta and America series helped visualize and popularize recent discoveries and inventions for a broad public.

Evidence suggests his prints directly influenced artists in colonial Mexico, providing models for religious murals and paintings. While perhaps not as revolutionary an innovator as some of his High Renaissance predecessors like Leonardo or Michelangelo, Stradano's strength lay in his synthesis, his prolific output, and his mastery of design for reproductive media. He influenced later Florentine artists, and his works continued to be studied and appreciated. Some sources mention an influence on figures like Massimiliano Franchetti (or perhaps Franchini), indicating his designs remained relevant. He remains a testament to the vibrant artistic exchange of the 16th century and the enduring power of well-crafted visual narratives.

Conclusion: A Versatile Master of Mannerism

Giovanni Stradano occupies a unique and important place in the history of late Renaissance art. A Fleming by birth and training, he became a quintessential Florentine artist, deeply integrated into the city's cultural fabric and the patronage network of the Medici dukes. His long career was marked by extraordinary productivity and versatility, demonstrating mastery in fresco painting, altarpieces, tapestry design, and, perhaps most consequentially, designs for the burgeoning print market.

His artistic style, a sophisticated fusion of Northern European attention to detail and Italian Mannerist elegance, allowed him to tackle an impressive array of subjects – from grand historical and religious narratives to intimate genre scenes, mythological tales, and pioneering depictions of scientific discovery and global exploration. Working alongside Giorgio Vasari and other leading artists of the day, he contributed significantly to the decoration of iconic Florentine landmarks like the Palazzo Vecchio.

Through the hundreds of engravings made after his designs, Stradano's influence radiated far beyond Italy, shaping visual culture across Europe and even in the Americas. He was a vital conduit for artistic ideas, translating complex narratives and novel subjects into clear, compelling images that could be widely reproduced and understood. Giovanni Stradano remains a compelling figure, embodying the cosmopolitanism, intellectual curiosity, and artistic dynamism of the late Renaissance. His works continue to offer valuable insights into the art, culture, and worldview of Medicean Florence and the broader European context of the 16th century.